Hoorn

Hoorn | |

|---|---|

City and municipality | |

| | |

| Nicknames: | |

Location within North Holland, Netherlands | |

| Coordinates: 52°39′N 5°4′E / 52.650°N 5.067°E | |

| Country | Netherlands |

| Province | North Holland |

| Subregion | West Friesland |

| City rights | 1357 (667 years ago) |

| Government | |

| • Body | Municipal council |

| • Mayor | Jan Nieuwenburg (PvdA) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 53.46 km2 (20.64 sq mi) |

| • Land | 20.38 km2 (7.87 sq mi) |

| • Water | 33.08 km2 (12.77 sq mi) |

| Elevation | −1 m (−3 ft) |

| Population (1 January 2021)[3] | |

| • Total | 73,619 |

| • Density | 3,613/km2 (9,360/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Hoornaar or Horinees |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 1620–1628, 1689, 1695 |

| Area code | 0229 |

| Website | www |

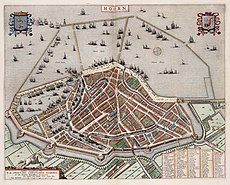

Hoorn (Dutch pronunciation: [ˈɦoːr(ə)n] ) is a city and municipality in the northwest of the Netherlands, in the province of North Holland. It is the largest town and the traditional capital of the region of West Friesland.[5] Hoorn is located on the Markermeer, 20 kilometers (12 mi) east of Alkmaar and 35 kilometers (22 mi) north of Amsterdam. The municipality has just over 73,000 inhabitants and a land area of 20.38 km2 (7.87 sq mi), making it the third most densely populated municipality in North Holland after Haarlem and Amsterdam.[3] Apart from the city of Hoorn, the municipality includes the villages of Blokker and Zwaag, as well as parts of the hamlets De Bangert, De Hulk and Munnickaij.

Hoorn is well known in the Netherlands for its rich history.[6] The town acquired city rights in 1357 and flourished during the Dutch Golden Age.[2] In this period, Hoorn developed into a prosperous port city, being home to one of the six chambers of the Dutch East India Company (VOC).[6] Towards the end of the eighteenth century, however, it started to become increasingly more difficult for Hoorn to keep competing with nearby Amsterdam.[5] Ultimately, it lost its function as port city and became a regional center of trade, mainly serving the smaller villages of West Friesland.[5] Nowadays, Hoorn is a city with modern residential areas and a historic city center that, due to its proximity to Amsterdam, is sometimes considered to be part of the Randstad metropolitan area.[7] Cape Horn and the Hoorn Islands were both named after this city.[8]

Etymology

[edit]

The origin of the name Hoorn – in archaic spelling Hoern, Horne or Hoirn(e) – is surrounded in myths.[9] According to old Frisian legends, the name comes from Hornus, a bastard son of King Redbad and brother of Aldgillis II, who presumably founded the city in 719 and named it after himself.[10] A different theory claims that the name was derived from a sign depicting a post horn, which hung from one of the taverns established by brewers from Hamburg in the early fourteenth century.[11]

According to Hadrianus Junius, the name could also be a reference to the city's horn-shaped port.[11] Others believed that the name was derived from damphoorn, a weed with a hollow stem that grew in the area at the time of the city's establishment.[12] The chronicler Theodorus Velius rejects this theory, as well as the assertion that the name comes from "Dampterhorn", which was thought to be the only remaining neighborhood of the flooded village of Dampten.[13]

One of the earliest mentions of Hoorn is found in a letter which states that in 1303, a merchant from Bruges was imprisoned in West Friesland near a place called "Hornicwed".[14] This phrase – although it is uncertain whether it actually refers to Hoorn – is a compound of the Middle Dutch words hornic, meaning "corner", and wed, meaning "shallow water".[15][16] It is likely that the name Hoorn was indeed derived from Middle Dutch hornic, or simply horn, and that the city was named for its location in a sharp bight of (the former) Lake Flevo.[9][12]

As a descendant of the reconstructed Proto-Germanic *hurnijǭ, the name Hoorn is a cognate with Danish and Norwegian hjørne, Icelandic horn, Swedish hörn(a), and West Frisian herne, which have all preserved the meaning of "corner".[9][17] In Modern Dutch, however, the word hoorn translates to "horn", both in an acoustic and anatomical sense.

History

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1398 | 3,800 | — |

| 1514 | 5,400 | +0.30% |

| 1550 | 8,000 | +1.10% |

| 1622 | 14,139 | +0.79% |

| 1632 | 13,500 | −0.46% |

| 1732 | 12,000 | −0.12% |

| 1795 | 9,551 | −0.36% |

| Source: Lourens & Lucassen 1997, pp. 62–63 | ||

Early history

[edit]In the beginning of the eighth century, the threat of Viking raids led to unrest in the Frisian Kingdom, causing many people to leave their hometowns and settle elsewhere.[10] Following this example, Hornus – a bastard son of Redbad – allegedly moved westward along with his companions and, in 719, built a settlement west of the river Vlie, which he named after himself.[10] This legendary settlement did not exist for long, as it burnt down only a few years later.[10]

In the Late Middle Ages, the site of present-day Hoorn was a swampy area that was not at all suitable for agriculture, as opposed to the more fertile inland.[12][18] Here, overproduction of dairy products led to the establishment of a marketplace within the domain of Zwaag, where excesses could be traded for other goods.[18] This marketplace was located near a sluice in the river Gouw, which was the most convenient passage into the Zuiderzee for the surrounding villages.[18]

The marketplace attracted many foreign traders, most notably from Hamburg and Bremen, who came to sell their goods (mostly beer) to the local population in return for butter and cheese.[18] This also brought three brothers from Hamburg to the area, who recognized its convenient location and decided to each build an inn near the marketplace to increase the sale of their beers.[19] The construction of these buildings was completed in 1316 and led to the expansion of the settlement, as more merchants from Northern Germany and Denmark now visited the place to trade.[12][19] As a result, the settlement quickly developed into a village, which was then given the name of Hoorn.[12] The town officially became a city in 1357, when Hoorn was awarded city rights by William V, Count of Holland, after a lump sum payment of 1,550 schilden.[5][a]

The Dutch Revolt

[edit]The revolution in Hoorn occurred without bloodshed. The town’s middle classes, after a futile attempt to assert Hoorn’s wish to garrison neither the Spanish army nor the rebel Sea Beggars, and after much debate, voted to open the city’s gates to the Beggars. By that time, Hoorn had already been flanked by the Beggar control of nearby Enkhuizen and Medemblik, and many rebellious exiles from earlier troubles returned to influence the town’s politics.[21]

Dutch Golden Age

[edit]Hoorn rapidly grew to become a major port city and a prosperous center of trade, which flourished during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, also known as the Dutch Golden Age.[5] It was the seat of the Committed Councils of West Friesland and the Noorderkwartier (Dutch: Gecommitteerde Raden) from 1573 to 1795, and the seat of the Admiralty of the Noorderkwartier from 1589 to 1795, together with Enkhuizen.[5][22] Furthermore, the city was an important home base for the Dutch East India Company (VOC), the Dutch West India Company (WIC) and the Noordsche Compagnie.[5]

The city's fleet plied the seven seas and returned laden with precious commodities from the East Indies. Exotic spices such as pepper, nutmeg, cloves and mace were sold at vast profits.[5] With their skill in trade and seafaring, sons of Hoorn established the city's name far and wide. In 1619, Jan Pieterszoon Coen (1587–1629), controversial for his violent raids in Southeast Asia, "founded" the capital of the Dutch East Indies, which he intended to name New Hoorn at first, though it was later decided that its name would be Batavia (present-day Jakarta).[23] A statue of Coen was placed on the city's central square Roode Steen in 1893.[24] In 1616, the explorer Willem Schouten, together with Jacob Le Maire, braved furious storms as he rounded the southernmost tip of South America. He named it Kaap Hoorn (Cape Horn) in honor of his home town.[25]

Eighteenth century to present

[edit]

Hoorn's fortunes declined somewhat in the eighteenth century. The prosperous trading port became little more than a sleepy fishing village on the Zuiderzee.[5] Following Napoleonic occupation, there was a period during which the town gradually turned its back on the sea.[5] It developed to become a regional center of trade, mainly serving the smaller villages of West Friesland.[5] Stallholders and shopkeepers devoted themselves to the sale of dairy products and seeds.[5] After the introduction of railways and metalled roads in the late nineteenth century, Hoorn rapidly took its place as a conveniently located and easily accessible hub in the network of towns and villages of North Holland. In 1932, the Afsluitdijk was completed, and Hoorn was no longer a seaport.

The years after World War II saw a period of renewed growth.[5] At the center of a flourishing horticultural region, the city developed a highly varied and dynamic economy.[5] In the 1970s, Hoorn was designated as an "overflow" city (groeikern) by the Dutch government to relieve pressure on the overcrowded Randstad region.[5] As a consequence, thousands of people swapped their cramped little apartments in Amsterdam for a family house with a garden in one of Hoorn's newly developed residential areas.[5]

Geography

[edit]

Hoorn is located in the east of the North Holland peninsula, on the northwestern shore of the Markermeer – the second largest freshwater lake of the Netherlands. The city occupies an arc of land in the south of West Friesland at the northernmost end of a small bay named Hoornse Hop. The landscape of Hoorn is mostly flat and the only elevated areas are the dikes on the southern outskirts of the city. The municipality is part of the safety region Noord-Holland Noord and the water board Hollands Noorderkwartier.

The harbor was enlarged in the mid-17th century by the construction of a peninsula, the Visserseiland (to the west of the harbor), and an artificial island, the Oostereiland (to the east).

Climate

[edit]

Hoorn has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb) strongly influenced by its proximity to the North Sea to the west, with prevailing westerly winds. Both winters and summers are considered mild, although winters can get quite cold, while summers are quite warm occasionally.

Hoorn, as well as most of the North Holland province, lies in USDA hardiness zone 8b. Frosts mainly occur during spells of easterly or northeasterly winds from the inner European continent. Even then, because Hoorn is surrounded on three sides by large bodies of water, nights rarely fall far below 0 °C (32 °F).

Summers are moderately warm with a number of hot days every month. The average daily high in August is 21.6 °C (70.9 °F), and 30 °C (86 °F) or higher is only measured on 1.8 days per year on average (2009–2018),[26] placing Hoorn in AHS heat zone 2. It is also common to have at least a couple of snowy days each year.

The Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute has one of its weather stations located in Berkhout, a village situated west of Hoorn. Climatological data from this station can be found in the table below. The record extremes range from −21.9 °C (−7.4 °F) to 34.6 °C (94.3 °F). The average annual precipitation is 855.5 millimetres (34 in).

| Climate data for Berkhout | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.8 (58.6) | 18.0 (64.4) | 22.3 (72.1) | 27.1 (80.8) | 29.8 (85.6) | 32.5 (90.5) | 35.7 (96.3) | 33.0 (91.4) | 29.7 (85.5) | 25.0 (77.0) | 19.1 (66.4) | 15.8 (60.4) | 35.7 (96.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 5.5 (41.9) | 5.9 (42.6) | 9.1 (48.4) | 12.9 (55.2) | 17.0 (62.6) | 19.2 (66.6) | 21.6 (70.9) | 21.6 (70.9) | 18.4 (65.1) | 14.2 (57.6) | 9.5 (49.1) | 6.2 (43.2) | 13.4 (56.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) | 3.3 (37.9) | 5.7 (42.3) | 8.8 (47.8) | 12.7 (54.9) | 15.1 (59.2) | 17.5 (63.5) | 17.4 (63.3) | 14.6 (58.3) | 11.0 (51.8) | 7.0 (44.6) | 3.9 (39.0) | 10.0 (50.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) | 0.6 (33.1) | 2.6 (36.7) | 4.6 (40.3) | 8.2 (46.8) | 10.8 (51.4) | 13.2 (55.8) | 13.1 (55.6) | 10.7 (51.3) | 7.8 (46.0) | 4.3 (39.7) | 1.5 (34.7) | 6.5 (43.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −15.4 (4.3) | −21.9 (−7.4) | −18.7 (−1.7) | −6.5 (20.3) | −1.7 (28.9) | 3.5 (38.3) | 6.7 (44.1) | 6.3 (43.3) | 2.2 (36.0) | −4.4 (24.1) | −6.7 (19.9) | −10.0 (14.0) | −21.9 (−7.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 74.9 (2.95) | 58.1 (2.29) | 51.1 (2.01) | 43.3 (1.70) | 56.0 (2.20) | 49.5 (1.95) | 76.0 (2.99) | 108.8 (4.28) | 78.1 (3.07) | 87.2 (3.43) | 85.4 (3.36) | 87.1 (3.43) | 855.5 (33.66) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 88 | 85 | 84 | 79 | 78 | 79 | 79 | 81 | 84 | 86 | 88 | 89 | 83 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 71.5 | 98.4 | 152.7 | 208.5 | 240.4 | 224.5 | 233.9 | 202.5 | 162.7 | 125.0 | 67.9 | 59.4 | 1,847.4 |

| Source 1: Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (1981–2010 normals, relative humidity)[27] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weergegevens.nl (2000–2019 extremes, precipitation, sunshine hours)[26][28] | |||||||||||||

Districts

[edit]The municipality of Hoorn consists of the city of Hoorn (postal codes 1620–1628) and the villages of Zwaag (postal code 1689) and Blokker (postal code 1695), which are further divided into the following districts:[29]

| No. | District | Population (2019) | Postal code |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Binnenstad (city center) | 5,570 | 1621 |

| 2 | Grote Waal | 7,680 | 1622 |

| 3 | Venenlaankwartier | 2,575 | 1623 |

| 4 | Hoorn-Noord | 5,460 | 1624 |

| 5 | Risdam-Zuid | 8,555 | 1625 |

| 6 | Nieuwe Steen | 1,250 | |

| 7 | Hoorn 80 | 10 | 1627 |

| 8 | Kersenboogerd-Zuid | 16,965 | 1628 |

| 9 | Kersenboogerd-Noord | 3,945 | |

| 10 | Risdam-Noord | 7,840 | 1689 |

| 11 | Zwaag | 3,145 | |

| 12 | Zevenhuis | 0 | |

| 13 | Bangert en Oosterpolder | 6,165 | 1689, 1695 |

| 14 | Westerblokker | 3,815 | 1695 |

Culture

[edit]

Architecture

[edit]Many of the houses in the historical city center date back to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, especially in the area north of the harbor. Other notable buildings include:

- Hoofdtoren (1464), the former harbor control tower

- Maria-/Kruittoren (1508), a tower built in late gothic style as part of the city wall

- Oosterpoort (1578), the only remaining city gate

- Waag (1609), weigh house at the junction of Grote Oost and Roode Steen

- Statenlogement (1613), former city hall

- Burgerweeshuis (1620), the former orphanage in the Korte Achterstraat

- Statencollege (1632), which houses the Westfries Museum

- Koepelkerk (1882), a Roman Catholic basilica

- Claes Stapelhof (1682), a hofje

Hoorn has notable modern buildings as well, such as:

- Schouwburg Het Park, a theater and congress center that was opened on 25 June 2004 by Queen Beatrix. The opening was delayed, as the fly tower collapsed in the night of 20 April 2001 due to faulty construction work.

Museums

[edit]Notable museums in Hoorn include:

Cemeteries

[edit]Local government

[edit]

Municipal council

[edit]| Party | 2014 | 2018 | 2022 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | ||

| Fractie Tonnaer | FT | 4.93 | 2 | 10.33 | 4 | 14.59 | 5 |

| Hoorn Lokaal | HL | 2.48 | 1 | 4.36 | 1 | 11.25 | 4 |

| GroenLinks | GL | 8.77 | 3 | 10.97 | 4 | 10.21 | 4 |

| ÉénHoorn | 1H | — | — | — | — | 10.15 | 4 |

| Christian Democratic Appeal | CDA | 9.48 | 3 | 10.35 | 4 | 9.79 | 3 |

| People's Party for Freedom and Democracy | VVD | 10.35 | 4 | 12.92 | 5 | 9.13 | 3 |

| Democrats 66 | D66 | 10.49 | 4 | 7.46 | 3 | 7.95 | 3 |

| Labour Party | PvdA | 14.69 | 5 | 9.12 | 3 | 7.84 | 3 |

| Sociaal Hoorn | SH | — | — | 5.74 | 2 | 6.70 | 2 |

| Liberaal Hoorn | LH | — | — | — | — | 6.39 | 2 |

| De Realistische Partij | DRP | — | — | 2.81 | 1 | 3.51 | 1 |

| Christian Union | CU | — | — | 2.79 | 1 | 2.48 | 1 |

| Hoornse Onafhankelijke Partij | HOP | 7.36 | 2 | 7.03 | 2 | — | — |

| V.O.C. Hoorn | VOC | 7.88 | 3 | 6.76 | 2 | — | — |

| Hoornse Senioren Partij | HSP | 5.32 | 2 | 5.01 | 2 | — | — |

| Hoorns Belang | HB | 5.24 | 2 | 4.35 | 1 | — | — |

| Socialist Party | SP | 12.02 | 4 | — | — | — | — |

| Hoorn+ | H+ | 0.99 | 0 | — | — | — | — |

| Total | 100.0 | 35 | 100.0 | 35 | 100.0 | 35 | |

| Party | Seats |

|---|---|

| Fractie Tonnaer | 5 |

| Hoorn Lokaal † | 4 |

| GroenLinks † | 4 |

| ÉénHoorn † | 4 |

| Christian Democratic Appeal † | 3 |

| People's Party for Freedom and Democracy † | 3 |

| Democrats 66 † | 3 |

| Labour Party | 3 |

| Sociaal Hoorn | 2 |

| Liberaal Hoorn | 2 |

| De Realistische Partij | 1 |

| Christian Union | 1 |

| † Coalition | 21 |

| Opposition | 14 |

| Total | 35 |

Municipal executive

[edit]As of 16 June 2022, the municipal executive of Hoorn consists of:[30][31]

| Mayor | Portfolio | Party | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan Nieuwenburg | Public Security, Regional Cooperation and Public Affairs | PvdA | |

| Aldermen | Portfolio | Party | |

| René Assendelft | Education, Harbors, Traffic and Transportation | HL | |

| Axel Boomgaars | Finance, Income, Culture and Diversity | GL | |

| Karin Hakhoff | Poverty Alleviation, Social Support, Elderly and Welfare | 1H | |

| Dick Bennis | Public Space, Environment, Neighborhood Affairs and Sport | CDA | |

| Marjon van der Ven | Housing, Urban Development and Public Health | VVD | |

| Arthur Helling | Economic Affairs, Tourism, Spatial Planning and Sustainability | D66 | |

Transport

[edit]

Railways

[edit]Hoorn is connected to the Dutch railway network and has two train stations: Hoorn and Hoorn Kersenboogerd. From these stations, it is possible to travel in the directions of Enkhuizen, Alkmaar and Amsterdam. It is also the starting point of the Hoorn–Medemblik heritage railway.

Roads

[edit]The A7 motorway, which runs from Zaandam to the German border via the Afsluitdijk, passes along Hoorn. The exit Hoorn North connects to the provincial road N302, also called Westfrisiaweg, which runs from Hoorn to Lelystad via the Houtribdijk.

Notable people

[edit]Born

[edit]The following is a list of notable people who were born in Hoorn:

Public figures

[edit]- Hadrianus Junius (1511–1575), humanist

- Cornelis Cort (ca. 1533 – ca. 1578), engraver

- Rombout Hogerbeets (1561–1625), jurist

- Willem Schouten (ca. 1567–1625), explorer

- Jonas Michaelius (1577 – after 1638), clergyman

- Cornelius Jacobsen May (ca. 1580 – after 1624), explorer

- Willem Bontekoe (1587–1657), explorer

- Jan Pieterszoon Coen (1587–1629), colonial administrator

- Jacques Waben (ca. 1590 – ca. 1634), painter

- Pieter Anthoniszoon Overtwater (ca. 1610–1682), merchant

- Birgitta Durell (1619–1683), Swedish industrialist

- Pieter Coopse (c. 1640–1673), painter and draughtsman

- Jacob Rotius (1644–1681), painter

- Martinus Houttuyn (1720–1798), botanist

- Adrianus Bleijs (1842–1912), architect

- Johan Messchaert (1857–1922), singer

- Aaf Bouber (1885–1974), actress

- Maria Elizabeth van Ebbenhorst Tengbergen (1885–1980), composer

- Bart Bok (1906–1983), American astronomer

- Anton Quintana (1937–2017), writer

- Corine Rottschäfer (1938–2020), model[32]

- Martin Brozius (1941–2009), actor

- George Baker (born 1944), singer

- Cees Renckens (born 1946), physician

- Joop van Wijk (born 1950), director

- Simone van der Vlugt (born 1966), writer

- Ron Blaauw (1967), chef

- Richard Tol (born 1969), economist

- Jan van Steenbergen (born 1970), linguist

- Maria Barnas (born 1973), writer and poet

- Wytske Postma (born 1977), politician

- Tim Knol (born 1989), singer-songwriter

- Stien den Hollander (born 2000), singer and rapper

Sportspeople

[edit]- Johannes van Hoolwerff (1878–1962), Olympic sailor

- Frans Hoek (born 1956), football player

- Ruud Heus (born 1961), football player

- Stephan van den Berg (born 1962), Olympic windsurfer

- Silvan Inia (born 1969), football player

- Frank de Boer (born 1970), football player

- Ronald de Boer (born 1970), football player

- Minouche Smit (born 1975), swimmer

- Marja Vis (born 1977), speed skater

- Marcelien de Koning (born 1978), Olympic sailor

- Vera Koedooder (born 1983), racing cyclist

- Coen de Koning (born 1983), Olympic sailor

- Tine Veenstra (born 1983), bobsledder

- Adrie Visser (born 1983), track cyclist

- Wil Besseling (born 1985), golfer

- Willemijn Karsten (born 1986), handball player

- Robert Krabbendam (born 1986), basketball player

- Pim Ligthart (born 1988), road cyclist

- Ruud Vormer (born 1988), football player

- Maikel van der Werff (born 1989), football player

- Roland Alberg (born 1990), football player

- Nadine Broersen (born 1990), track and field athlete

- Marco Bizot (born 1991), football player

- Lorenzo Ebecilio (born 1991), football player

- Nicole Koolhaas (born 1991), volleyball player

- Brandley Kuwas (born 1992), football player

- Sonny Stevens (born 1992), football player

- Paul Kok (born 1994), football player

- Bas Schouten (born 1994), racing driver

- Nadine Visser (born 1995), track athlete

- Inessa Kaagman (born 1996), football player

- Maaike Boogaard (born 1998), racing cyclist

- Dani de Wit (born 1998), football player

- Dagmar Boom (born 2000), volleyball player

- Kenzo Goudmijn (born 2001), football player

- Sontje Hansen (born 2002), football player

Residing

[edit]The following is a list of people who were born elsewhere, but are notable (former) residents of Hoorn:

- David Pietersz. de Vries (ca. 1593–1655), explorer

- Andreas Cellarius (1596–1665), cartographer

- Jan Albertsz Rotius (1624–1666), painter

- Miep Gies (1909–2010), helper of the Frank family

- Edgar Vos (1931–2010), fashion designer

- Milly Scott (born 1933), singer and actress

- Bonnie St. Claire (born 1949), singer

- Ernesto Hoost (born 1965), kickboxer

- Sylvana Simons (born 1971), presenter and politician

- Steven van Weyenberg (born 1973), politician

- Lobke Berkhout (born 1980), Olympic sailor

- Dean Saunders (born 1981), singer

- Ben Saunders (born 1983), singer

International relations

[edit]Partner cities

[edit]Hoorn is twinned with the following cities and municipalities:

Friendships

[edit] Lewes, Delaware, United States

Lewes, Delaware, United States

- Lewes was the site of the first European settlement in Delaware: a whaling and trading post that Dutch settlers led by David Pieterszoon de Vries established in 1631 and named Zwaanendael.[33] Upon their arrival in the Delaware Bay, they entered a kill which De Vries named "Hoornkill" after his hometown Hoorn.[34] Nowadays, the city's Zwaanendael Museum is located in a replica of the Statenlogement, the former city hall of Hoorn. Although Hoorn and Lewes have never officially been partner cities, there is close informal relationship between the two towns. Delegations from Hoorn and Lewes have visited each other's cities in light of Lewes's 375th and Hoorn's 650th anniversary in 2006 and 2007 respectively.[35]

Malacca City, Malaysia (since 1989)

Malacca City, Malaysia (since 1989)

- In 1641, the Dutch conquered the colony of Malacca from the Portuguese.[36] During the Dutch rule, the iconic Stadthuys was built – a replica of the first city hall of Hoorn, which was demolished in 1797.[37][38] Hoorn and Malacca became sister cities in 1989, but the partnership was officially ended in 2005.[35] The cities still maintain an informal relationship as "friendship cities".

Notes

[edit]- ^ The exact date on which Hoorn received its city rights is debatable. At the time, each year began on Holy Saturday rather than 1 January. The original certificate states that the city rights were granted "in the year (…) 1356, on the Sunday after Our Lady's Day”, which corresponds to 26 March 1357 on the Gregorian calendar. However, the same certificate also states that the city rights were granted by “William, Duke of Bavaria, Count of Holland and Zeeland, Lord of Friesland, and Verbeider of Hainaut". As his title changed to Count of Hainaut when his mother, the Countess of Hainaut, died on 23 June 1356, it has been argued that Hoorn must have received its city rights one year earlier, on 26 March 1356.[20] Nonetheless, the city of Hoorn celebrated its 600 and 650 year anniversary in 1957 and 2007 respectively.

- ^ Initiated by Blokker and Lot, before they merged into their respective municipalities in the 1970s.

References

[edit]- ^ Pannekeet, Jan (1995). Westfries Woordenboek. Wormerveer: Uitgeverij Noord-Holland. p. 67. ISBN 90-71123-01-4.

- ^ a b "City of the Golden Age". Ik hou van Hoorn. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "Regionale kerncijfers Nederland". CBS Statline (in Dutch). Statistics Netherlands. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ "Postcodetool for 1625HV" (in Dutch). Actueel Hoogtebestand Nederland. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Hoorn: Historie". Westfries Genootschap (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Hoorn & Enkhuizen in the Golden Age". Holland.com. 6 October 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Nieuwe steden in de Randstad: Verstedelijking en suburbaniteit (PDF) (in Dutch). PBL. September 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ "De ontdekking van Kaap Hoorn". Het Scheepvaartmuseum (in Dutch). 28 January 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "Hoorn (geografische naam)". etymologiebank.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d Knaap, J.P.H. van der (2008). Hoornse sagen, legenden, volksverhalen (PDF) (in Dutch). Hoorn: Vereniging Oud Hoorn. p. 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Plaatsnamen en hun betekenis". Volkoomen.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Halma, François (1725). Nidek, Mattheus Brouërius van (ed.). Tooneel der Vereenigde Nederlanden en onderhorige landschappen, geopent in een algemeen historisch, genealogisch, geographisch en staatkundig woordenboek (in Dutch) (Volume 1 ed.). Leeuwarden: Hendrik Halma. pp. 431–432.

- ^ Kwaad, Frans J.P.M. "Velius: Kroniek van Hoorn". kwaad.net (in Dutch). Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Lesger, C.M. (1990). Hoorn als stedelijk knooppunt: stedensystemen tijdens de late middeleeuwen en vroegmoderne tijd (in Dutch). Uitgeverij Verloren. p. 24. ISBN 9070403277. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Hornic – Middelnederlandsch Woordenboek". De Geïntegreerde Taalbank (in Dutch). Instituut voor de Nederlandse taal. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Wedde – Middelnederlandsch Woordenboek". De Geïntegreerde Taalbank (in Dutch). Instituut voor de Nederlandse Taal. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Horn (in het water uitspringende hoek land)". etymologiebank.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Hoorn in de Middeleeuwen". Vereniging Oud Hoorn. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ a b Velius, Theodorus (1648). Chroniick van Hoorn, daer in verhaelt werden des selven Stadts eerste begin, opcomen, en gedenckweerdige geschiedenissen, tot op den jare 1630 (in Dutch). Hoorn: Isaac Willemsz. p. 3.

- ^ Cox, Joost C.M. (2006). "Stedelijke trots en stadsrechtvieringen" (PDF). Holland, Historisch Tijdschrift (in Dutch). 38 (2): 63–75. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ van Nierop, Henk (2009). Treason in the Northern Quarter: War, Terror, and the Rule of Law in the Dutch Revolt. Princeton University Press. pp. 63–67.

- ^ "Admiraliteit in het Noorderkwartier (1589-1795)". Huygens ING. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Jan Pieterszoon Coen (1587-1629) – Stichter van Batavia". Historiek (in Dutch). 21 August 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ "Omstreden standbeeld J.P. Coen van sokkel gevallen". De Volkskrant (in Dutch). 16 August 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ M, Jan (11 March 2014). "Hoorn". Netherlands Tourism. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Gemiddelden en extremen Berkhout" (in Dutch). Weergegevens.nl. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ "Berkhout, langjarige gemiddelden, tijdvak 1981–2010" (PDF) (in Dutch). Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ "Maandrecords Berkhout" (in Dutch). Weergegevens.nl. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ "Wijken, buurten en woonplaatsen in Hoorn". AlleCijfers.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Nieuwe wethouders Hoorn geïnstalleerd". Hoornsdagblad.nl (in Dutch). 17 June 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ "College van B & W". Gemeente Hoorn (in Dutch). Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ "Nederlands eerste Miss World Corine Spier-Rottschäfer overleden". NOS (in Dutch). 24 September 2020. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020.

- ^ Munroe, John A. Colonial Delaware: A History. Millwood, New York: KTO Press; 1978; pp. 9–12.

- ^ Vincent, Francis. A history of the state of Delaware. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: J. Campbell; 1870; pp. 130.

- ^ a b "Horinezen bij feestje in Lewes, USA" (in Dutch). Hoorngids. 26 April 2006. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Witt, Dennis de. "Malacca, a Dutch conquest forgotten". The Dutch Courier (May 2001). Malaysian Dutch Descendants Project. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ "The Stadthuys of Malacca". Holland Focus. 4 July 2006. Archived from the original on 25 September 2009. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ Overbeek, Henk. "'t Stadhuys van Hoorn – Hoornse Gevelstenen en andere Huistekens". Vereniging Oud Hoorn. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

Literature

[edit]- Lourens, Piet; Lucassen, Jan (1997). Inwonertallen van Nederlandse steden ca. 1300–1800. Amsterdam: NEHA. ISBN 9057420082.