Hurricane Kilo

Hurricane Kilo rapidly strengthening over the central Pacific on August 29 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 22, 2015 |

| Extratropical | September 11, 2015 |

| Dissipated | September 15, 2015 |

| Category 4 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 140 mph (220 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 940 mbar (hPa); 27.76 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | None |

| Damage | Minimal |

| Areas affected | Hawaii, Johnston Atoll, Japan, Russian Far East |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2015 Pacific hurricane and typhoon seasons | |

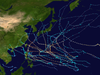

Hurricane Kilo, also referred to as Typhoon Kilo, was a powerful and long-lived tropical cyclone that traveled more than 4,000 miles (6,400 kilometers) from its formation point southeast of the Hawaiian Islands to its extratropical transition point to the northeast of Japan. Affecting areas from Hawaii to the Russian Far East along its long track, Kilo was the fifth of a record eight named storms to develop in the North Central Pacific tropical cyclone basin during the 2015 Pacific hurricane season.

Kilo formed from a tropical disturbance that was first identified by the U.S. National Hurricane Center (NHC) on August 17, about 1,150 mi (1,850 km) southeast of the Big Island of Hawaii. Initially, a mid-level ridge to the disturbance's east imparted easterly wind shear over the system, preventing it from organizing. Eventually, the shear decreased and the disturbance became a tropical depression on August 22. The wind shear decreased further on August 26, and the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Kilo at 18:00 UTC[a] that day while approaching Johnston Atoll. Amid high sea surface temperatures and low vertical wind shear, Kilo began to quickly strengthen while being steered westwards by a new mid-level ridge, attaining hurricane status on August 29.

Over the next 24 hours, Kilo rapidly intensified into a Category 4 hurricane, with its winds nearly doubling from 75 mph (120 km/h) to 140 mph (220 km/h).[b] Kilo reached its peak intensity at the end of this strengthening phase, with a minimum barometric pressure of 940 mbar (hPa; 27.76 inHg). Around this time, Kilo was one of three hurricanes at Category 4 intensity spanning the Eastern and Central Pacific basins, the first such occurrence in recorded history. On September 1, Kilo crossed the International Date Line and became a typhoon. Kilo progressed westward over the open ocean as a typhoon in the Western Pacific for over a week while fluctuating in intensity. Kilo continued on as a tropical cyclone until September 11, when it curved northeastwards to the east of Japan and became an extratropical cyclone near the western Kuril Islands of Russia. Kilo's extratropical remnant continued northeastward until dissipating over the Russian Far East on September 15.

As a tropical depression, Kilo brought heavy rain and flash flooding to much of the Hawaiian island chain. Many roads were rendered impassable after Kilo's rainbands dropped several inches of rain in Kauai, Maui, and Oahu, and flooding forced the closure of several stores, businesses and schools in the latter island. Rainfall from Kilo set a daily rainfall record for the month of August in Honolulu, with 3.53 in (90 mm) falling in less than 24 hours. Despite the severe flooding, damage in Hawaii was minor. A tropical storm warning was issued for Johnston Atoll as Kilo passed closely to the north, though the hurricane ultimately passed the territory without leaving any damage. The combined remnants of Kilo and Tropical Storm Etau led to flooding over portions of Japan and Russia.

Meteorological history

[edit]

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The tropical disturbance that would become Kilo first developed on August 17, about 1,150 mi (1,850 km) southeast of the Big Island of Hawaii, within a broad, low-level trough. The disturbance began to move slowly northeast out of the trough on August 19 while remaining poorly organized, producing intermittent bursts of convection. The system then turned to the northwest, steered by a mid-level ridge located to its northeast. This ridge produced easterly wind shear over the disturbance, initially keeping remained poorly organized. However, a brief surge in convection and weak low-level circulation center (LLCC) developed over the system on August 20, though the two features separated later that day. As a ridge to the disturbance's north steered it more quickly to the west-northwest, wind shear relaxed over the system, allowing its LLCC to re-consolidate. The disturbance developed into a tropical depression by 6:00 UTC on August 22.[1][c]

The newly-formed depression continued to the west-northwest over the following days, initially hindered by continued easterly shear. It then turned more northward on August 24 and slowed as it neared the edge of its steering ridge. The slow-moving cyclone gradually became more organized as a new ridge strengthened to its northwest, allowing wind shear to lessen in the surrounding environment. Turning southwestwards, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Kilo at 18:00 UTC on August 26 as it drifted towards Johnston Atoll. Kilo continued to intensify as it moved southwestwards, passing northwest of the territory as a strong tropical storm. Turning west under the influence of another ridge to its north, Kilo achieved hurricane status at 6:00 UTC on August 29.[1][2]

Kilo was situated within an environment of warm waters and low vertical wind shear when it reached hurricane status. Within these favorable environmental conditions, the storm began a significant bout of rapid intensification. In a 12-hour period from 6:00 to 18:00 UTC on August 29, Kilo intensified from a low-end, 75 mph (120 km/h) Category 1 hurricane to a high-end, 125 mph (200 km/h) Category 3 major hurricane. The hurricane continued to intensify as it turned more west-northwestward, and the cyclone achieved peak intensity as a powerful Category 4 hurricane at 6:00 UTC on August 30, with maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (225 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 940 mbar (28 inHg).[1] Kilo weakened slightly later that day, though its intensity plateaued at 125 mph (200 km/h) by August 31. A break in the mid-level ridge steering Kilo allowed it to turn northward as it approached the International Dateline. By 18:00 UTC, Kilo had crossed the dateline and entered the Western Pacific basin, at which time it was re-classified as a typhoon.[1][2]

Kilo began to weaken as it crossed into the Western Pacific, encountering cooler waters and higher wind shear. The storm weakened to a Category 2-equivalent typhoon on September 1 as it entered the basin. Kilo maintained its intensity for another day as its motion slowed and the storm turned westward. Late on September 3, Kilo turned to the southwest again, and underwent another brief weakening trend, bottoming out as an 85 mph (135 km/h), Category 1-equivalent typhoon on September 5, due to increased southwesterly wind shear.[3] Kilo then turned back to the west, along the Tropic of Cancer, and began a new intensification phase on September 6. The storm reached its secondary peak intensity by 00:00 UTC on September 7, with maximum sustained winds of 105 mph (170 km/h), near the intersection of the Tropic of Cancer and the 170th meridian east.[2][4]

Kilo began to weaken again later that day as its eye became irregularly shaped, and convection eroded over the southern semicircle of the storm.[5] Embarking on a more northwestward course, deep convection associated with Kilo decreased in intensity and coverage through September 8 as drier air wrapped into the core of the typhoon.[6] Kilo only weakened gradually, however, with its winds slowly diminishing to severe-tropical-storm-force by 12:00 UTC on September 9, as its center became exposed from its convective activity within an environment of even stronger shear.[7][8] Thereafter, Kilo accelerated northwestward, with a gradual northward bend as it became caught up in the middle latitude westerlies east of Japan. The storm flatlined in intensity on September 10 as it passed Japan, turning to the north-northeast as it began to undergo extratropical transition.[9] Kilo then resumed weakening on September 11, before transitioning to an extratropical cyclone at 12:00 UTC that day, near the Kuril Islands of Russia,[2] over 4,000 mi (6,400 km) from its genesis point.[1] Kilo's extratropical remnant raced northeastward, crossing into the Sea of Okhotsk on September 12 and absorbing the remnants of Severe Tropical Storm Etau that same day.[10] The remnants of Kilo continued to the northeast before dissipating over the Russian Far East on September 15.[2]

Records

[edit]While Kilo was traversing the Central Pacific basin as a major hurricane, hurricanes Ignacio and Jimena were also active as Category 4 hurricanes. This marked the first time on record that three concurrent major hurricanes were active east of the International Date Line, as well as the first time three Category 4 hurricanes were simultaneously active in the Eastern/Central Pacific basins. Additionally, Ignacio was active within the Central Pacific basin alongside Kilo, marking the first time two simultaneous major hurricanes were active within the Central Pacific. Kilo also became the third tropical cyclone of the 2015 season to cross the Date Line, surpassing the previous mark of two tropical cyclones crossing the dateline in one season, which occurred in 1997.[1]

Preparations and impact

[edit]Hawaii

[edit]A flash flood watch was issued by the National Weather Service on August 23 for all Hawaiian islands, ending at 6:00 p.m. HST on August 24. The weather service also issued a Marine Weather Statement for heavy showers and thunderstorms. The watch was upgraded to a flash flood warning later that day for the Big Island.[11]

Moisture associated with Kilo, then a tropical depression, significantly affected Hawaii. Honolulu received 4.48 in (114 mm) of rain from early on August 23 to August 25, including 3.53 inches (90 mm) on August 24, setting a record for the highest rainfall amount for any day in August. Rain rates of 3 to 4 inches (76 to 102 mm) per hour were estimated by radar near Kauai. Thunderstorms over the island chain resulted in nearly 10,000 lightning strikes from August 23 to 24.[12] Kohala Mountain Road on the Big Island was closed after water covered its surface,[13] while floodwaters made the Piilani Highway in Maui impassable.[14] In Kipahulu, the Hana Highway flooded, cutting off transportation in parts of the town.[15] Numerous schools closed near the Hana area, and the Hana Highway was closed for several miles across.[16] Inundation forced the closures of the Waiʻanapanapa and Iao Valley state parks.[17][18] The towns of Kahana and Honokowai reported neighborhoods being flooded as well.[19] In Oahu, flash floods inundated areas near the Ala Moana Center and a flooded a Walmart store.[20] More than a foot of water flooded roads in Ala Moana.[21] In that town, the sewer system failed during the floods, with thousands of gallons of sewer water flowing out of manholes.[22] An off-ramp of Interstate H-1 near the University of Hawaii was rendered impassable.[23] In addition, two lanes of the highway near Waimalu were flooded and closed.[24] Several schools on Oahu closed on August 24 due to floods and power outages.[25]

Johnston Atoll

[edit]At 21:00 UTC on August 23, a Tropical Storm Watch was issued for Johnston Atoll. The watch was upgraded to a Tropical Storm Warning at 03:00 UTC the next day. The warning was cancelled on August 25 as the threat of tropical-storm-force sustained winds diminished. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service stationed personnel on the atoll as Kilo passed within 35 mi (55 km) to the north. Despite the close pass, overall minimal effects from Kilo were reported on Johnston Atoll.[1]

Japan and Russia

[edit]As Kilo weakened to the east of Japan, it sent a large plume of moisture and strong winds northwestward into the country. These features contributed to the strengthening of the extratropical remnants of Tropical Storm Etau and led to several days of heavy rainfall and destructive flooding across Japan, though most of the destruction was due to Etau.[26] After Kilo absorbed the remnants of Etau, the resultant extratropical cyclone went on to affect portions of the Russian Far East with moderate rainfall and gusty winds. A maximum of 3.5 in (90 mm) of rain were recorded at weather stations in the urban localities of Preobrazheniye and Olga, while strong winds affected the city of Vladivostok. No serious damage was recorded in Russia.[27]

See also

[edit]- Weather of 2015

- Tropical cyclones in 2015

- List of Category 4 Pacific hurricanes

- Hurricane Uleki (1988) – Followed a very similar path and had a similar peak intensity

- Hurricane John (1994) – Furthest-travelling tropical cyclone on record, also crossed International Dateline and became a typhoon

- Hurricane Ioke (2006) – Had a similar track, also crossed Dateline and became a typhoon

- Hurricane Genevieve (2014) – Also crossed over the International Dateline and became a typhoon

- Hurricane Hector (2018) – Another long-lasting Category 4 hurricane that affected Hawaii

Notes

[edit]- ^ All times are in Coordinated Universal Time, unless otherwise noted

- ^ All maximum wind speeds are 1-minute sustained, unless otherwise noted

- ^ Kilo was operationally thought to have developed and reached tropical storm strength on August 20, when its LLCC initially formed; thus, it received a name before Hurricane Loke, which formed on August 21

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Thomas Birchard (October 10, 2018). Hurricane Kilo (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Honolulu, Hawaii: Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 9, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Sopko, Steven P.; Falvey, Robert J. Annual Tropical Cyclone Report 2015 (PDF) (Report). Honolulu, Hawaii: Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- ^ "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 03C (Kilo) Warning Nr 59". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 22, 2024. Retrieved October 21, 2023.

- ^ TC Realtime CP032015 - Major Hurricane KILO (Report). Fort Collins, Colorado: Regional and Mesoscale Meteorology Branch. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

- ^ "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 03C (Kilo) Warning Nr 59". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 22, 2024. Retrieved October 21, 2023.

- ^ "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 03C (Kilo) Warning Nr 77". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 22, 2024. Retrieved October 21, 2023.

- ^ "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 03C (Kilo) Warning Nr 81". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 22, 2024. Retrieved October 21, 2023.

- ^ "Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Storm 03C (Kilo) Warning Nr 84". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 22, 2024. Retrieved October 21, 2023.

- ^ "Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Storm 03C (Kilo) Warning Nr 85". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 22, 2024. Retrieved October 21, 2023.

- ^ "RSMC Tropical Cyclone Best Track 1518 Etau (1518)". Japan Meteorological Agency. October 21, 2015. Archived from the original on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2023-11-09.

- ^ "Flash flood warning, watch and marine advisories for Hawaii". Hawaii247. August 23, 2015. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ "Kilo Became Three Weeks Old Before Dissipating". The Weather Channel. September 11, 2015. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Event: Flash Flood in Hawaii County, Hawaii, 2015-08-23 17:15 HST-10 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. August 23, 2015. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Event: Flash Flood in Maui County, Hawaii, 2015-08-23 19:15 HST-10 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. August 23, 2015. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Event: Flash Flood in Maui County, Hawaii, 2015-08-24 06:45 HST-10 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. August 24, 2015. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Event: Flash Flood in Maui County, Hawaii, 2015-08-24 07:10 HST-10 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. August 24, 2015. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Event: Flash Flood in Maui County, Hawaii, 2015-08-24 07:46 HST-10 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. August 24, 2015. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Event: Flash Flood in Maui County, Hawaii, 2015-08-24 07:55 HST-10 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. August 24, 2015. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Event: Flash Flood in Maui County, Hawaii, 2015-08-25 08:15 HST-10 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. August 25, 2015. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Event: Flash Flood in Honolulu County, Hawaii, 2015-08-24 03:01 HST-10 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. August 24, 2015. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Event: Flash Flood in Honolulu County, Hawaii, 2015-08-24 04:06 HST-10 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. August 24, 2015. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Event: Flash Flood in Honolulu County, Hawaii, 2015-08-24 11:30 HST-10 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. August 24, 2015. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Event: Flash Flood in Honolulu County, Hawaii, 2015-08-24 03:53 HST-10 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. August 24, 2015. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Event: Flash Flood in Honolulu County, Hawaii, 2015-08-24 04:34 HST-10 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. August 24, 2015. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Event: Flash Flood in Honolulu County, Hawaii, 2015-08-24 05:50 HST-10 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. August 24, 2015. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ "Japan floods: Rescue work continues after deadly disaster". British Broadcasting Corporation. September 11, 2015. Archived from the original on September 11, 2015. Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- ^ "Экс-тропический шторм "Атау" обрушил на Приморье очень сильный дождь" [Ex-tropical storm "Atau" brought down very heavy rain on Primorye] (in Russian). Gismeteo. September 10, 2015. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved September 11, 2015.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Weather Service.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Weather Service.

External links

[edit]- 03C.KILO from the United States Naval Research Laboratory

- General Information of Typhoon Kilo (1517) from Digital Typhoon

- JMA Best Track Data of Typhoon Kilo (1517) (in Japanese)

- JMA Best Track (Graphics) of Typhoon Kilo (1517)