Issedones

The Issedones (Ἰσσηδόνες) were an ancient people of Central Asia at the end of the trade route leading north-east from Scythia, described in the lost Arimaspeia[1] of Aristeas, by Herodotus in his History (IV.16-25) and by Ptolemy in his Geography. Like the Massagetae to the south, the Issedones are described by Herodotus as similar to, yet distinct from, the Scythians.

Location

[edit]

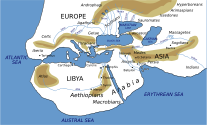

The exact location of their territorial span in Central Asia is unknown. The Issedones are "placed by some in Western Siberia and by others in Chinese Turkestan," according to E. D. Phillips.[2]

Herodotus, who allegedly got his information through both Greek and Scythian sources, describes them as living east of Scythia and north of the Massagetae, while the geographer Ptolemy (VI.16.7) appears to place the trading stations of Issedon Scythica and Issedon Serica in the Tarim Basin.[3] Some speculate that they are the people described in Chinese sources as the Wusun.[4] J.D.P. Bolton places them further north-east, on the south-western slopes of the Altay mountains.[5]

Another location of the land of the Issedones can be inferred from the account of Pausanias. According to what the Greek traveller was told at Delos in the second century CE, the Arimaspi were north of the Issedones, and the Scythians were south of them:

At Prasiai [in Attika] is a temple of Apollo. Hither they say are sent the first-fruits of the Hyperboreans, and the Hyperboreans are said to hand them over to the Arimaspoi, the Arimaspoi to the Issedones, from these the Skythians bring them to Sinope, thence they are carried by Greeks to Prasiai, and the Athenians take them to Delos." - Pausanias 1.31.2

The two cities of Issedon Scythia and Issedon Serica have been identified with five cities in the Tarim Basin: Qiuci, Yanqi, Shule, Gumo, and Jingjue, while Yutian is identified with the latter.

The Issedones may also correspond to the Saka Tasmola culture of Central Asia.[6]

Description

[edit]The Issedones were known to Greeks as early as the late seventh century BCE, for Stephanus Byzantinus[7] reports that the poet Alcman mentioned "Essedones" and Herodotus reported that a legendary Greek of the same time, Aristeas son of Kaustrobios of Prokonnessos (or Cyzicus), had managed to penetrate the country of the Issedones and observe their customs first-hand. Ptolemy relates a similar story about a Syrian merchant.

The Byzantine scholiast John Tzetzes, who sites the Issedones generally "in Scythia", quotes some lines to the effect that the Issedones "exult in long flowing hair" and mentions the one-eyed men to the north.

According to Herodotus, the Issedones practiced ritual cannibalism of their elderly males, followed by a ritual feast at which the deceased patriarch's family ate his flesh, gilded his skull, and placed it in a position of honor much like a cult image.[8] In addition, the Issedones were supposed to have kept their wives in common.[9] This may indicate institutionalized polyandry and a high status for women (Herodotus IV.26: "and their women have equal rights with the men").

Cannibalism controversy

[edit]The archeologists E. M. Murphy and J. P. Mallory of the Queen's University of Belfast have argued (Antiquity, 74 (2000):388-94) that Herodotus was mistaken in his interpretation of what he imagined to be cannibalism. Recently excavated sites in southern Siberia, such as the large cemetery at Aymyrlyg in Tuva containing more than 1,000 burials of the Scythian period, have revealed accumulations of bones often arranged in anatomical order. This indicates burials of semi-decomposed corpses or defleshed skeletons, sometimes associated with leather bags or cloth sacks. Marks on some bones show cut-marks of a nature indicative of defleshing, but most appear to suggest disarticulation of adult skeletons. Murphy and Mallory suggest that, since the Issedones were nomads living with cattle herds, they moved up the mountains in summer, but they wanted their dead to be buried at their winter camp; defleshing and dismemberment of the people who died in summer would have been more hygienic than allowing the corpses to decompose naturally in the summer heat. Burial of the dismembered remains would have taken place in fall after returning to winter camp, but before the ground was frozen completely. Such procedures of defleshing and dismemberment may have been mistaken for evidence of cannibalism by foreign onlookers.

Murphy and Mallory do not exclude the possibility that the flesh removed from the bodies was consumed. Archeologically these activities remain invisible. But they point out that elsewhere, Herodotus names another tribe (Androphagi) as the only group to eat human flesh.

On the other hand, Dr. Timothy Taylor[10] points out:

- 1. Herodotus reports that the so-called "Androphagoi" are the "only" people in the region to practice cannibalism. However, a distinction should be drawn between "aggressive gustatory cannibalism" (i.e., hunting humans for food) and the ritualized, reverential practices reported among the Issedones and Massagetae.

- 2. Scythian-type peoples were renowned embalmers and presumably would have no need for funerary defleshing to delay decomposition of the corpse.

- 3. Herodotus specifically describes the removal of the meat and mixing it with other foodstuffs to make a funerary stew.

Dr. Taylor concludes: "Inferring reverential funerary cannibalism in this case is thus the most academically cautious approach".

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The few fragmentary quoted lines are assembled by Kinkel, Epicorum graecorum fragments, 243-47.

- ^ Phillips, "The Legend of Aristeas: Fact and Fancy in Early Greek Notions of East Russia, Siberia, and Inner Asia" Artibus Asiae 18.2 (1955, pp. 161-177) p 166.

- ^ Ptolemy's information appears to come at several removes from a Han guide of the first century CE, according to Phillips (Phillips 1955:170); it would have been translated from Persian to Greek by the traveller Maes Titianus for his itinerary, used by Marinus of Tyre as well as Ptolemy.

- ^ Golden (1992), p. 51

- ^ Bolton, J.D.P. (1962). Aristeas of Proconnesus. pp. 104–118.

- ^ Ivanov, Sergei Sergeevich (2023). "Asia, Steppe, East: Early Iron Age Pastoralist Cultures". Reference Module in Social Sciences. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-90799-6.00253-6.

Based on some information from literary sources it was suggested that the areas of the Tasmola Culture distribution can be correlated with the territory of the Issedones tribal group habitat. The Pazyryk Culture of the Altai Mountains, which also covered the mountains of Eastern Kazakhstan, could be associated with the semi-legendary people of the "gold guarding vultures"

- ^ Under "Issedones".

- ^ As Herodotus tells us (IV.26): "The Issedonians are said to have these customs: when a man's father is dead, all the relations bring cattle to the house, and then having slain them and cut up the flesh, they cut up also the dead body of the father of their entertainer, and mixing all the flesh together they set forth a banquet." Similar practices obtained among the Massagetae (Herodotus I.217) and the Scythians (Plato, Euthydemus 299, Strabo 298), Phillips notes, mentioning "similar customs in medieval Tibet" (Phillips 1955:170).

- ^ Minns, Ellis Hovell (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 885.

- ^ Taylor, "The Edible Dead", British Archaeology, 59 (June 2001) on-line

Sources

[edit]- Golden, Peter (1992). An Introduction of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Asia and the Middle East. O. Harrassowitz. ISBN 3-447-03274-X.

External sources

[edit]- Herodotus. The Histories. Book 4.

- Scythians at Livius.org Archived 2013-11-12 at the Wayback Machine

- T. Sulimirski. The Sarmatians in the series Ancient Peoples and Places (Thames & Hudson,1970)

- E. D. Phillips, "The Legend of Aristeas: Fact and Fancy in Early Greek Notions of East Russia, Siberia, and Inner Asia" Artibus Asiae 18.2 (1955), pp. 161–177.