John Burley

John Burley | |

|---|---|

Broncroft Castle today. | |

| Member of the English Parliament for Shropshire | |

| In office 1399–1401 Serving with Thomas Young Sir Hugh Cheyne | |

| Preceded by | Richard Chelmswick Sir Fulk Pembridge |

| Succeeded by | 1399: Sir John Cornwall 1401: Sir Adam Peshale |

| In office 1404–1406 Serving with January: George Hawkstone October: John Darras | |

| Succeeded by | John Burley, David Holbache |

| In office 1410–1411 Serving with 1410: David Holbache 1411: Sir Adam Peshale | |

| Preceded by | Sir John Cornwall, David Holbache |

| Succeeded by | Robert Corbet, Richard Lacon |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1360 |

| Died | 1415–16 Broncroft |

| Cause of death | Probably dysentery contracted at Siege of Harfleur |

| Nationality | English |

| Spouse | Juliana |

| Children | William Burley, John Burley, Edmund Burley, one daughter |

| Residence | Broncoft Castle |

| Occupation | Lawyer, landowner, soldier. |

John Burley (died c. 1416) was an English lawyer, soldier, and a knight of the shire (MP) for Shropshire six times from 1399. He was a justice of the peace for Shropshire and sheriff of the county from 10 December 1408 – 4 November 1409. A key member of the Arundel affinity, he helped muster forces to combat the Glyndŵr Rising and died a short time after accompanying Thomas Fitzalan, 12th Earl of Arundel on Henry V's first expedition to France.[1]

Origins and identity

[edit]John Burley's origins are obscure, not least because his name was not uncommon. Burley is a toponymic surname signifying a meadow or clearing by a fortified place and is found fairly widely across the Midlands and the North of England.[2] He has been portrayed as a nephew of Simon de Burley, an influential courtier executed by the Merciless Parliament at the behest of the Lords Appellant.[3] However, this makes little sense in view of John Burley's political position and apparent social origins. He seems to have been a son of a John Burley of Wistanstow in southern Shropshire and a nephew of John Burnell of Westbury, Shropshire.[1] The lawyer John Burley is known from a quitclaim deed of 1397 to have had at that time three brothers: Nicholas, portioner of the church of Westbury, James and Edmund.[4] There seems to have been pattern of having a lawyer and a cleric in each generation.

His name is rendered variously in medieval documents, including Bureley, Boerlee and Borley. His coat of arms is given as: vert, 3 boars' heads couped close 2 and 1 argent.[5]

Early career 1380–99

[edit]The Ludlow estates

[edit]The Burley and Burnell estates in South Shropshire were closely entwined with those of Sir Richard Ludlow, a much more powerful landowner who had inherited eleven manors in Shropshire.[6] For about a decade, until Ludlow's death late in 1390, Burley worked closely with him as one of his feoffees. For example, Burley was one of a group of feoffees whom Ludlow was licensed to appoint on 20 January 1383 in relation to lands at Hodnet and elsewhere,[7] the aim being to ensure they passed to John Ludlow, Richard's brother, should he die sine prole, as he actually did. As a feoffee Burley exercised many of Ludlow's responsibilities and powers on his behalf. The register of John Gilbert, the Bishop of Hereford, shows that Burley jointly exercised the advowson of the church at Wistanstow, presenting Edmund de Ludlowe as rector on 6 August 1385.[8]

Edmund de Ludlow was also a feoffee of Sir Richard and presumably a close relative. John Burley also acted with him for more humble clients. For example, as feoffees they assisted Philip Herthale with the inheritance of a mere garden in Ashford Carbonell.[9] However, things clearly did not go smoothly with Edmund and on 30 July 1390 Sir Richard replaced him with a chaplain, John de Stretton.[10] Edmund was aggrieved and took his case to the Arches Court, which found in his favour. Subsequently, he alleged that Burley and Sir Richard's retinue had nevertheless physically expelled him from his benefice.[6] Sir Richard died before the suit came to court: Edmund possibly prevailed, as someone of his name was also incumbent at Wistanstow later in the decade.[11]

Ludlow's inquisition post mortem at Shrewsbury in January 1391 showed that, despite his great wealth, technically he held no land at all in the county, as the king, Richard II, had licensed him to vest everything in Burley and other feoffees,[12] a stratagem that allowed him to avoid payment of impositions like feudal relief as well as free disposal of the properties according to his own wishes. Ludlow had appointed three groups of feoffees to hold his properties in trust and Burley was a member of all three groups. On 8 February the king instructed his escheator in Shropshire to meddle no further with the Ludlow estates and remitted the feoffees' homages and fealties for 6s. 8d.[13]

Lawyer to the nobility

[edit]Alongside his work for Ludlow, Burley extended his reach as a feoffee and lawyer upwards into the local nobility. The History of Parliament Online names the most influential nobles of Shropshire during the period as the earls of Arundel, Stafford and March, and the Lords Talbot, Furnival and Burnell.[14] Burley is known to have worked for all but one of these.

Possibly the first was Gilbert Talbot, 3rd Baron Talbot. Early in 1387 Burley joined Talbot's contingent to fight under Richard FitzAlan, 11th Earl of Arundel in a successful naval campaign against the French and their allies in the English Channel.[1] Talbot died on 24 April that year[15] and in June Burley was one of those fined for acting as feoffee and entering his estate at Wormelow without a licence from the king.[16] Whether a real oversight or a legal fiction, this had the effect of registering the transfer to Gilbert's heir, Richard, the 4th Baron Talbot. At this point Burley was dealing with the lower reaches of the nobility, but during his stewardship of their estates the Talbots grew increasingly powerful by marriage and Burley reaped the rewards of skilled and loyal service. Richard Talbot's wife, Lady Ankaret, who was heiress to the Barony of Strange of Blackmere,[15] settled a small estate on Burley, who paid two marks into the royal hanaper to ensure the gift was recorded on 17 February 1408.[17] For this Burley added to his patrimony a house, 2½ virgates of land 8 acres of meadow and 6 of woodland. Shortly after this, on 4 May, John Burley, described as "of Bromcroft," probably drew up the paperwork for the transfer of Corfham Castle and its associated estates to Ankaret's son John Talbot, 6th Baron Furnivall. This involved two other feoffees, Geoffrey Lowther and Hugh Burgh, a retainer of Lord Furnivall who had become rich by marriage on lands that were the focus of a Corbet family dispute.[18] After Ankaret's death on Ascension Day, 1413, Burley oversaw the transfer, and the estates were released rapidly by a royal mandate to the escheator on 15 July.[19]

One of the Talbot estates was held of the marcher lord Hugh Burnell, 2nd Lord Burnell, who had also granted land at Abbeton to Burley.[1] Burnell was a marcher lord based in central Shropshire, where his family were the eponyms of Acton Burnell, with its fortified manor house, and where he was governor of Bridgnorth.[20] Burnell's second wife, Joyce Botetourt, brought him considerable wealth, as she was the cousin (once removed) and heiress of Hugh la Zouche, a wealthy Leicestershire landowner who died in July 1399.[21] Burley acted as a feoffee to speed the transfer of the manor of Mannersfee in Fulbourn, Cambridgeshire, which was held of the Bishop of Ely.[22] The escheator was mandated to take the fealty of Burley and the other feoffees by the new régime of Henry IV on 21 May 1400.[23] However, there were considerable legal difficulties with some parts of the manor and the matter seems not to have been fully resolved until June 1403.[24] Presumably John Burley's services were much valued, as his son, Edmund, was presented to a portion of Holdgate parish by Hugh Burnell in 1411.[25] The three clerics of the church were described as canons,[26] as if it were a collegiate church attached to Holdgate Castle. Edmund Burley must have been appointed to the deaconry, as its advowson was held by the Burnells.[27] The favour shown by Burnell to the Burleys suggests that they may have been relatives.

It was possibly through Burnell that Burley became involved with Edmund Stafford, 5th Earl of Stafford, as Stafford's sister Katherine was the mother of Burnell's first wife, Philippa de la Pole.[20] He is known to have acted as seneschal or steward to Stafford's court, for which he received a salary of £6 13s. 4d.[28] It is known that he was also a member of Stafford's Council, as a record is extant of the accountant receiving 1s. per day for travelling to summon him to a meeting in 1399.

By 1400 Burley was also serving the borough of Shrewsbury as a steward. This carried a fee of £2 or £3 per year, which was supplemented by occasional gifts of wine and clothing.[1] It may be that this post was obtained through the FitzAlans, who held the Earldom of Arundel.

The Arundel connection

[edit]

The FitzAlan earls of Arundel were the richest and most important landowners in Shropshire,[29] and for more than a century they had also been great landowners in the South of England, where their power was concentrated in Sussex. Their profits were invested in further expansion. Although this was only to a lesser extent in Shropshire, they were the dominant force in the county's politics and parliamentary representation: between 1386 and 1397 eleven of the twenty MPs were clients or allies of Richard FitzAlan, 11th Earl of Arundel.[14] Arundel formalised his relationship with many of his followers with small grants of land, rather than the annuities characteristic of bastard feudalism. His inquisition post mortem showed that Burley received from him a moiety of Brotton, worth 30s. annually:[30] this seems to be additional land at Brockton, where Burley was lord of the manor.[31] One of Earl Richard's concerns in Shropshire was with the civic and commercial development of Oswestry, the original power base of his dynasty. He made John Burley his steward of the town by 1393.[32] This is made clear in a record of Arundel's court at Oswestry, dated 7 May 1393 and sealed by Burley, in which Thomas Salter and his wife Matilda are granted succession to Thomas's ancestral estates for the rather large feudal relief of £10, already paid in three instalments.[33] In 1395 Burley became a feoffee for the important Arundel marcher lordships of Chirk and Chirkland.[34] The other feoffees included Thomas Arundel, the Archbishop of York and the earl's brother, as well as other Arundel lawyers like Thomas Young[35] and David Holbache.[36] As a servant of Arundel, Burley was now regularly appointed a justice of the peace: for example a commission of 18 June 1394[37] was followed by another on 1 May 1396.[38]

Overthrow of Richard II

[edit]

Earl Richard was one of the Lords Appellant, the leaders of the baronial opposition to Richard II, and was executed in 1397. Burley's activities during these momentous events seems to have been entirely routine. In July 1397, immediately after Arundel's arrest, Burley was involved in some sort of deal with John Eyton that required a reciprocal agreement to pay each other a substantial £200 the next Michaelmas.[39] Later in the year he is recorded taking recognizances as usual, including an undertaking from William Glover of Ludlow for £60.[40] Business continued, with other smaller clients employing him, along with his usual colleagues. On 7 March 1398 he and Thomas Young were among the feoffees appointed by Isabel de Eylesford to deal with her manors of Brimfield, Herefordshire, and Buildwas, Shropshire:[41] a licence to complete the business by reciprocally enfeoffing Isabel was not issued until April 1402,[42] long after the looming power struggle had reached conclusion, and problems at Brimfield delayed completion until February 1403, by which time Isabel was remarried.[43] Such legal complexities unfolded to an entirely different rhythm from politics. An almost adjacent entry in the Patent rolls for 4 February shows how delicately the king, evidently worried by spreading disaffection, was handling Shropshire people affected by Arundel's attainder. In this case, in an issue that might have been initiated by Burley, the king ensured that an Oswestry brewer would not be out of pocket, as he had invested heavily in premises granted by Arundel.[41] Burley's own position with the régime seems to have been little affected and he was reappointed as a justice of the peace on 16 September 1398, after a lapse of little more than a year:[44] more or less the same interval as previously.

When the king's enemies struck, the defection of Shropshire was a critical juncture in the rapid collapse that followed. Burley quickly rallied to Thomas FitzAlan, the dispossessed claimant to the earldom, when he returned with Henry Bolingbroke in 1399.[1] Adam of Usk's account of the rebels' march through Shropshire makes clear that they met with a welcome in the county and hints at how this shaped the future power structure of the county, with Thomas Arundel, now Archbishop of Canterbury giving ecclesiastical sanction to the new arrangements.

| Latin | English |

|---|---|

| Demum idem dux cum exercitu suo aput Herffordiam, secundo die Augustii, in palacio episcopi se hospitavit; et in crastino se versus Cestream movit, et in prioratu de Lempster pernoctavit. Et postea nocte proxima aput Lodelaw in castro regis, vino ibidem inhorriato non-parcens, pernoctavit. Ubi presencium compilator ab eo et a domino Cantuariensi fratrem Thomam Prestburi, magistrum in theologia, ipsius contemporarium Oxonie, monachum de Salopia, tunc carceribus per regem Ricardum detentum, eo quod contra excessus suos quedam merito predicasset, ab huiusmodi carceribus liberari, et in abbatem monasterii sui erigi, optinuit. Demum per Salopiam transitus ibi per duos dies mansit; ubi fecit proclamari quod excercitus suus se ad Cestriam dirigeret, tamen populo et patrie parceret, eo quod per internuncios se sibi submiserant.[45] | At length the duke came to Hereford with his host, on the second day of August, and lodged in the bishop's palace; and on the morrow he moved towards Chester, and passed the night in the priory of Leominster. The next night he spent at Ludlow, in the king's castle, not sparing the wine which was therein stored. At this place, I, who am now writing, obtained from the duke and from my lord of Canterbury the release of brother Thomas Prestbury, master in theology, a man of my day at Oxford and a monk of Shrewsbury, who was kept in prison by king Richard, for that he had righteously preached certain things against his follies; and I also got him promotion to the abbacy of his house. Then, passing through Shrewsbury, the duke tarried there two days; where he made proclamation that the host should march on Chester, but should spare the people and the country, because by mediation they had submitted themselves to him.[46] |

Following the successful coup by the coalition of Bolingbroke and the Arundels, Burley's long-term client Hugh Burnell was one of the barons who accepted the surrender of Richard II at the Tower of London.[20] Prestbury, the new abbot, and his abbey were to become foci for Burley's generosity as he prospered under the new Lancastrian régime and the restored Arundel supremacy in Shropshire.

Later career 1399–1415

[edit]Supporting the new order

[edit]During the last 15 years of his career, Burley was very heavily involved in the affairs of the Arundel dynasty, its affinity within Shropshire and its work on behalf of the House of Lancaster. His commitment to the FitzAlan earls can only have become more complete with the death of Stafford, another major client, at the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403, although, it never induced him to give up his work for other clients. Burley seems to have been trusted from the outset by new Lancastrian régime as politically and ideologically reliable, and he began to reap the rewards of loyalty.

Burley was a knight of the shire for the first time in the parliament of October 1399, sometimes considered a Convention Parliament. He was accompanied by Thomas Young, already a close associate and an executor of Richard FitzAlan, the executed earl.[14] The parliament ratified the assumption of the throne by Bolingbroke, who became Henry IV. It also repealed the measures of the September 1397 parliament that had attainted the 11th Earl of Arundel, allowing Thomas FitzAlan to assume the title and take over its lordships. During the course of the parliament Burley acquired the wardship of Robert Corbet from Thomas Percy, 1st Earl of Worcester and he later also purchased the wardship of Corbet's estates. Corbet became an important member of the Arundel affinity.[47]

Burley received the commission of the peace on 28 November 1399, in the new dynasty's first round of appointments,[48] and it was renewed without break on 16 May 1401. Thereafter he was a JP continuously until March 1413: he and Thomas Young served more regularly than any others. As his eminence grew in the county, Burley also served as its Sheriff for the year 1409.[3]

Further parliaments

[edit]The 12th Earl kept a tight grip on the county's representation. The capable and reliable Burley was returned five more times: in 1401, twice in 1404, in 1410, and for a final time in 1411. In 1401 he was paired with the aged Sir Hugh Cheyne, who was of the Mortimer affinity and custodian of Ludlow Castle during the minority of Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March.[49] In 1404 he was accompanied first by the heavily indebted George Hawkstone[50] but to the second parliament of the year by John Darras, another member of the Arundel affinity, who had been an active and violent participant in the Corbet family's feuds.[51] In 1410 he was again MP alongside an Arundel ally: the lawyer David Holbache who was to represent the county no less than seven times.[36] Finally, in 1411, he sat with Sir Adam Peshale, a slippery and quarrelsome character who represented Shropshire four times and the neighbouring county of Staffordshire as often.[52]

Public order and resistance

[edit]As well as taking part in regular law enforcement, Burley frequently received commissions to deal with particularly serious or problematic incidents. In September 1401 disorder in the county was sufficiently serious for the king to include Burley in a special commission, headed by the Earls of Arundel, Stafford and Worcester, to "enquire about all treasons, insurrections, adherences to the king's enemies, murders and rapes in the county of Salop."[53] The king and his circle tended to see disorder as a consequence of sedition. On 11 May 1402 Burley was one of those commissioned in Shropshire to combat propaganda against Henry IV.[54] The responsibility of those named was not only to argue publicly that the king was devoted to the customs of the realm but to hunt down and round up those "preaching among other things that the king has not kept the promises he made at his advent into the realm and at his coronation."[55] Burley was sent to tackle cases of murder, as at Hereford in January 1403,[56] He was also the man for serious outbreaks of disorder, as when, a month later, organised poachers attacked a deer park at Kingswood in Shropshire, driving off game and breaking down the hated fencing.[57] In this and other cases, the dividing line between common felony and real challenge to the social order was tenuous. In March 1404 Arundel, Burley and others were commissioned to deal with offences committed by adherents of Owain Glyndŵr[58]

Burley was also ordered to investigate complex and important matters of property and inheritance, and these too could have a bearing on the king's interests or public order. On 18 November 1400 he was sent with Lee, Holbache and Sir John Wiltshire, a close friend of Arundel,[59] to investigate a case where it was suspected a dead man's property was being concealed from the king,[60] a form of tax evasion. The following month Burley and Darras were among those sent in pursuit of Sir Thomas and Richard Harcourt.[61] On the death of Sir William Shareshull, a furious dispute had broken out over his estates in Shropshire and Straffordshire, which he had inherited from his wealthy grandfather, the eminent lawyer Justice William de Shareshull.[62] To keep their grip on the estates, the Harcourts had forcibly prevented the escheator taking possession of them. In March 1404 Burley and John Kinghtley, another JP, were ordered to discover the whereabouts of Fulk, the son and heir of John Mawddwy and Elizabeth Corbet.[63] The case was one in into which Burley must have had considerable insight, bordering on a conflict of interest, as many of his friends and associates had already been embroiled in the Corbet family disputes that underlay the case. In 1390 nine Shropshire and Herefordshire landowners had been summoned to interview by the king and his council under pain of 200 marks each because of their violence in supporting one side in the dispute.[64] They had included John Darras, Sir Sir Roger Corbet (the father of Burley's ward), Sir Richard Ludlow (Burley's client), Sir Hugh Cheyne and Thomas Young (both of whom served alongside Burley as MPs for Shropshire, and the latter a close associate in Arundel's service). Whatever the outcome of this particular phase in the dispute, the Mawddwy estates were ultimately to pass to Hugh Burgh, Burley's associate as a feoffee for the Talbots, who married the missing heir's sister.[18]

The Glyndŵr Rising

[edit]

John Burley and Thomas Lee were with Arundel on the bench in 1400 when the first indictments were brought against Owain Glyndŵr, resulting in his proclamation as a traitor. The event was recalled as late as the 1431 parliament, when some of the subsequent anti-Welsh legislation was reaffirmed.[65]

After the Battle of Shrewsbury, the king and Arundel were able to take the fight against the Glyndŵr Rising back into Wales. The Parliament of 1404 took place in Coventry and at it instructions to monitor the musters for the forthcoming campaign were issued to John Burley, Thomas Young and Sir John Cornwall.[66] The abbot of Lilleshall Abbey was ordered to take an oath of loyalty from Cornwall and Burley, the king had "appointed them controllers of all the arrayers and leaders of men at arms, hobelars and archers of the marches of England towards North Wales."[67] A formal commission to the same effect was issued under Letters patent on 24 March 1405.[68] Prince Henry had been appointed the king's lieutenant in North Wales, with effect from 27 April. He was to conduct a punitive expedition and would need initially 500 men-at-arms and 2650 archers, with the need for archers rising to 3000 after the first two months. Burley, Young and Cornwall were to supervise the musters of troops in both Shropshire and Cheshire and to report back on numbers. They were also to investigate and report back on gentry and nobles already under arms and drawing pay from the royal coffers. Similar responsibilities continued for some time, as Arundel himself was closely involved in the Welsh campaigns. On 7 October 1405, Burley and Cornwall, this time with a cleric, Roger Haldenby, were commissioned to raise troops for Arundel to garrison castles in North Wales and Shropshire.[69] However, there seems to have been sedition on both sides of the border. Also 7 October, the same day, Arundel, Burley and Cornwall were issued a commission of oyer and terminer to hunt down people in Shropshire who were secretly supplying the rebels. In January 1406 Prince Henry was commissioned to extend his operations to South Wales, while Cornwall, Burley and Haldenby were commissioned to raise further troops in the Welsh Marches.[70] Around the time of the campaigns Burley had the distinction of being called to a great council by the king.[71]

Shrewsbury was a crucial bulwark against the Welsh revolt which was prolonged and expensive. In July 1407, Burley was appointed to a committee to attend to the fortifications of Shrewsbury, auditing the accounts of customs granted by Richard II for the purpose.[72] The other members were the Earl of Arundel, Edward Charleton, 5th Baron Cherleton, Burnell, Holbache and Thomas Prestbury, the abbot of Shrewsbury Abbey.

Lollardy

[edit]On 11 May 1407 Burley was commissioned, along with Prestbury, Arundel, Charleton, Burnell, Holbache, Young and Lee, to track down and imprison those "preaching, publishing or maintaining or holding schools of any sect or doctrine contrary to the Catholic faith and the sacraments of the Church."[73] The commission was also addressed to the bailiffs of Shrewsbury, Ludlow and Bridgnorth. The Lollard movement was a major preoccupation of Archbishop Arundel, who later appointed Prestbury Chancellor of Oxford University to further his campaign in academic circles.[74] The Testimony of William Thorpe, records an unauthorised sermon by a Lollard preacher at St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury on 17 April 1407,[75] suggesting that this commission was a direct response. Thorpe claimed to have been arrested on the advice of Holbache and questioned by Prestbury, before being sent to Arundel in London in June.[76] It has been suggested that John Mirk's homily on Corpus Christi was a counterblast to the sermon. A similar commission had been addressed to the authorities in Coventry a fortnight earlier and the Midlands was known to be a Lollard stronghold. Burley seems to have been considered a reliable upholder of orthodoxy. He was a member of the Palmer's Guild of Ludlow,[77] essentially a friendly society providing a chantry for its members in St Laurence's Church, Ludlow, as well as insurance against some worldly misfortunes:[78] the liturgical practices underpinning such societies were diametrically opposed to Lollard teaching.

Working for Arundel

[edit]Burley continued to work for Arundel on issues concerning his estates. When, on 25 January 1407, the earl granted a new charter to Oswestry,[79] enhancing its liberties and giving it a commercial monopoly over a considerable area,[80] the steward Burley's name headed the list of witnesses.[81] These included Holbache and Richard Lacon, a hero of the fight against Glyndŵr and another ally of Arundel who had married profitably into the Corbet family.[82] In the summer of that year Burley again acted as feoffee for an important collection of Arundel's estates, including Shrawardine and other estates in Shropshire and Wiltshire, in a transaction that gave a lifetime interest to the earl's wife, Beatrice, Countess of Arundel.[83] On 3 September 1411 Burley was made Arundel's attorney, along with Richard Wakehurst, a Sussex man who handled similar business for the earl in the South of England.[84] They were needed because Arundel was sent abroad to negotiate for a marriage between the Prince of Wales and a daughter of John the Fearless, the Duke of Burgundy:[85] a mission that proved abortive. Burley's relationship with the earl was reinforced by the accession of two of his sons, William and John, to the Arundel affinity.[1]

Disputes and resolutions

[edit]

Burley was closely involved in a particularly protracted and complex feud at Shrewsbury, involving the politicians Nicholas Gerard and Urian St Pierre. This began in 1407 with St Pierre buying from feoffees property, mainly valuable urban plots in Abbey Foregate and elsewhere, that Gerard was hoping to inherit from his grandfather.[86] It led to three assizes of novel disseisin and a violent attack by Gerard on his opponent on Castle Street.[87] Finally they compromised, with St Pierre handing over the property, but Gerard compensating him by resigning in his favour the constableship of Shrewsbury Castle – a post he finally acquired on 15 February 1413.[88] The legal costs to the borough, including fees to Burley, the serjeant-at-law and the attorney, came to £2 10s.

Burley's relations with Arundel's brother-in-law, William de Beauchamp, 1st Baron Bergavenny, were uneven and led to at least one protracted dispute. Around 1400 Burley bought the tenancy-in-chief of Munslow in Corvedale from Beauchamp, and probably later acquired the terre tenancy or lordship of the manor.[89] In April 1407 Burley was associated with such illustrious figures as Archbishop Arundel, the earl's uncle, in a transaction designed to settle a number of estates on Joan, the wife of Beauchamp and sister of Arundel.[90] However, less than a month later, he was reported by the dean of Wenlock as being involved in a violent dispute with Beauchanp over the advowson of Munslow. Beauchamp had presented William Catchpole to the rectory in 1396.[91] It seems that Burley assumed he had then bought the advowson from Beauchamp, along with the tenancy-in-chief, as the two had previously gone together.[92] However, according to the dean's report, Beauchamp had presented a chaplain, Hugh, to the church, and Burley had challenged his institution. An inquisition into the matter had been constituted but Burley, described as the lord of the vill, had terrorised its members:[93] not the first time he was using force to settle an ecclesiastical dispute. The issue was remitted to court proceedings and in June the king issued a writ to Bishop Robert Mascall to forbid his admitting anyone to the living pending a resolution of the issue between himself and Beauchamp, on one side, and Burley and Walter Carpenter, Burley's nominee, on the other.[94] At some stage the bishop presented and instituted his own registrar, John Sutton, who had first notified him of the case, to the church. By April 1410 the issue had been resolved, with Beauchamp recognising Burley as patron, and Sutton resigning to be presented to the church by Burley himself.[95]

By this time, Burley was involved in an investigation on Beachamp's behalf. John Cornwall had been rewarded for his services to the king with the grant of the lucrative keepership of Morfe and Shirlett, areas of Royal forest, apparently in preference to Nicholas Gerard, who had been promised the post.[96] However, in 1410 Beauchamp complained of breaches of his customary manorial and grazing rights at Worfield in Morff Forest, not mentioning Cornwall by name but speaking of "certain evildoers."[97] William Ferrers, 5th Baron Ferrers of Groby, echoed Beauchamp's complaints. In March the king mandated Arundel, Burley, Holbache, Young, and Lord Furnival to carry out inquiries. It seems that Cornwall was undeterred and, after William Beauchamp's death, his widow Joan reiterated his complaints against Cornwall.[98] The same commission of inquiry was renominated. The issue finally came to a head in 1413 when John Marshall, Dean of the royal free chapel at Bridgnorth, explicitly named Cornwall as the culprit in harassing himself and his tenants at Claverley.[99] The king forced Cornwall to resign and on 13 February sent Burley, Holbache and two other lawyers to investigate after the event.

Endemic violence

[edit]While the Arundel affinity's dominance was generally imposed through adept use of the law and civil authority, there was an undertow of violence and intimidation and this became increasingly open and notorious after 1410, as Arundel's affinity clashed with supporters of most of the county's other magnates. Burley was very close to the perpetrators of violence: his son, his former ward and his future executors were involved in some of the most sensational outrages. These led to complaints about the prevalence of bad governance and murder in Shropshire at the Fire and Faggot Parliament, held in Leicester in 1414.[14] Many cases came to court at the last ever regional session of the Court of King's Bench, held at Shrewsbury in Trinity term of 1414. Henry V was present in person,[100] along with William Hankford, the Chief Justice of the King's Bench, to make a show of taking seriously the complaints against his most powerful supporter in the region, and much of what is known of the violence is derived from allegations made at that court.

It was alleged that in May 1411 Burley's younger son, John, lay in wait with ten other armed men at Onibury to ambush John Stanton, perhaps an inhabitant of Stanton Lacy, who was visiting Stokesay. After a long wait, Stanton appeared and John Burley unhorsed him with his sword and then set about him with the same weapon. There could be little doubt of the intention to kill, as he struck seven potentially fatal blows. In March 1412 Roger Corbet, Robert's younger brother, led an armed force of forty men to raid the rectory of St Peter's Church, Edgmond, where he had a quarrel with the incumbent, Nicholas Peshale.[101] Peshale lost all his sheep, cattle, household goods and silverware. The church belonged to Shrewsbury Abbey, to which Corbet and other Arundel men were significant benefactors,[102] so it is likely the attack had something to do with the abbey's internal politics: moreover, the Peshales were allied to the Earls of Stafford. When the royal tax collectors arrived the following year the Corbet brothers set their servants on them. One of them, Roger Leyney, got a writ against them, provoking Roger Corbet to pursue him as far as Dunstable with a body of five armed men. There Corbet confronted Leyney with the words "Who made the so hardy to putte any bille to the Kyng to undo me with all?"[103] He then attacked the man with his sword, bata, naufra, et ses chambes coupa, luy endonant pluseurs autres horribles ployes a son final anientisement et grauntz maheime, eusi q'il estoit en point de mort: beating and wounding the man, hacking at his legs and causing horrible sufferings, maiming him seriously, to the point of death. The same term, maihem, is used in allegation that in August 1413 the younger John Burley and his gang carried out another armed ambush, attacking William Munslow, from the name possibly one of his father's tenants, at Ludlow, although on this occasion the victim seems to have escaped death. In 1413, as Lord Furnival seemed to be acquiring still more power by inheriting his mother's estates – a process assisted by Burley as feoffee – open hostilities broke out between his and Arundel's men.[14] Early in May 1413 an armed force of 800 from Oswestry, where Burley was steward, had appeared at Pitchford and billeted itself without payment on Lord Burnell's tenants.[104] It was alleged that Arundel's men had raided Much Wenlock with 2000 Cheshire men on 18 May 1413, a circumstance they attributed to their efforts at law enforcement directed towards the criminal Furnival.[47] The elder Burley was very familiar with the mechanics of raising forces like these, which were essentially the same mercenaries used in border warfare and Welsh campaigns. One of those most prominently accused in relation to the events at Wenlock was his friend Richard Lacon.[82] Despite his closeness to the perpetrators and his record of both legitimate force and criminal intimidation, Burley was left unscathed by the accusations. Arundel, along with Richard Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick, was at the very centre of Henry V's tight-knit group of advisers.[105] The king's intervention in Shropshire in 1414 was a bold move designed to show that even the most powerful magnates were not above the law.[106] It provoked the laying of almost 1800 indictments and the prosecution of about 1600 individuals. However, only seven were prosecuted to the point where they were required to give bonds for £200. Ultimately Arundel and Furnival stood surety for their affinity members and most received formal pardons.[14]

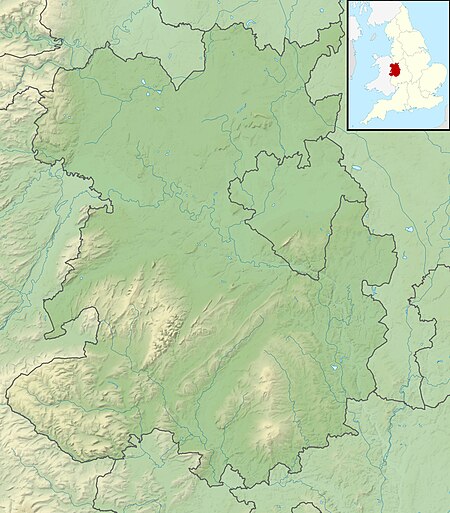

Landowner

[edit]From origins on the lower margins of the landed gentry class John Burley rose to become a substantial landowner. His investments were concentrated in Corvedale and the neighbouring valleys, between Wenlock Edge and the Clee Hills, although he had land elsewhere.

- Ashfield, in the parish of Ditton Priors. The estate had been divided into three parts in the mid-13th century.[107] Burley and his wife acquired two of the parts and in 1401 paid 20s. in the hanaper to avoid any further complications from taking over lands held in capite without licence.[108]

- Brockton, an estate in the parish of Shipton, formerly part of the Ludlow estates, where Burley was lord of the manor by 1397[31]

- Strefford, another manor formerly belonging to the Ludlows.

- Munslow, where Burley bought the lordship from Lord Bergavenny.[89]

- Broncroft, where John Burley or his son William built a large home, described by John Leland as "a very goodly place like a castel."[109]

- Acton Scott parish, where Burley and his wife exchanged land to acquire property at the hamlets of Alcaston and Henley from Richard and Isabella Bachorne on 15 May 1397.[110] Burley took out a bond to Bachorne for £100 on 25 May.[111]

- Alveley, on the east bank of the River Severn, where he had property that was to fund his chantry.[112]

Death

[edit]War with the Armagnac party in France was a serious threat when Burley began to establish a chantry for himself and his wife Juliana. On 1 December 1414, using the rector of Upton Magna and vicar of Wrockwardine as his feoffees, and for a fine of £20, he received a licence to alienate in mortmain substantial property to Shrewsbury Abbey,[112] where his associate Prestbury was still abbot. These were holdings at Alveley and included two messuages, seven tofts, 2½ virgates and 21 acres of land, 8 acres of meadow, 12 acres of woodland, 57s. 1d. in rents and a third share in a weir. In return the abbey promised to find a chaplain from within the monastic chapter to celebrate mass daily for Burley and Juliana in the chapel of St Katharine.

In July 1415 he enlisted with Thomas Fitzalan, 12th Earl of Arundel to take part in Henry 's first expedition to France. Arundel's force consisted of 100 men-at-arms and 300 mounted archers,[113] including the Corbet brothers.[47] The Siege of Harfleur brought a devastating outbreak of dysentery, which was the main cause of death and invalidity in his retinue. A quarter of the force were casualties of the siege.[114] Both Burley and Arundel were invalided home and did not take part in the Agincourt campaign. Arundel returned to England on 28 September[115] to recuperate at Arundel Castle, attended by William Burley,[116] but died there on 13 October. Burley returned to England on 4 October.[1]

Burley made a nuncupative will in October 1415,[28] which suggests that he was very ill by this time, although he declared that his mind and memory were still intact. The contents were not greatly illuminating. After commending his soul to his Omnipotent Creator, he simply confirmed that his real property should go to his legal heirs.[117] He had presumably made all the necessary arrangements for tax avoidance and a smooth succession well before. He left the disposition of his moveable property to his executors, whom he named as Richard Lacon and Roger Corbet. The will was proved on 18 February 1416, so he must have been dead for some time by that date.

Marriage and family

[edit]John Burley's wife was Juliana. She is mentioned frequently as a participant with him in property deals. Owen and Blakeway's History of Shrewsbury asserted that she was the "daughter of Reginald lord Grey de Ruthyn,"[118] presumably meaning Reginald Grey, 2nd Baron Grey de Ruthyn. The History of Parliament makes clear that there is no known evidence for this[1] and Evelyn Martin pointed out a century ago that there are contrary assertions in other sources.[28] However, the idea persists, and the Victoria County History in 1998 maintained and possibly aggravated the confusion by describing Burley as "Reynold, Lord Grey of Ruthin's brother-in-law,"[89] still citing Owen and Blakeway as evidence,[119] in this case presumably referring to Reginald Grey, 3rd Baron Grey de Ruthyn. Burley and the Greys belonged to very different social strata and even William Burley, starting from a much wealthier background, married only into the lower, if prosperous, gentry, connected to urban trade.[116]

John and Juliana Burley had at least three sons and a daughter. The three sons, all mentioned above, were:

- William Burley, John Burley's heir, sometime Speaker of the House of Commons. His coat of arms was: Argent, a lion rampant Sable, debruised by a fess counter-gobony Or and Azure.[120]

- John Burley, a particularly brutal member of the Arundel affinity.

- Edmund Burley, a cleric who was made a portioner of Holdgate by Hugh Burnell.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). BURLEY, John I (d.1415/16), of Broncroft in Corvedale, Salop. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Hanks et al, p.101.

- ^ a b Martin, p. 229.

- ^ Shropshire Archives Document Reference: 103/1/5/7 at Discovering Shropshire's History.

- ^ Martin, p. 227.

- ^ a b Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). LUDLOW, Sir Richard (c.1361–1390), of Hodnet, Salop. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls 1381–1385, p. 220.

- ^ Registrum Johannis Gilbert, p. 119.

- ^ Shropshire Archives Document Reference: LB/5/2/963 at Discovering Shropshire's History.

- ^ Registrum Johannis Trefnant, p. 174.

- ^ R. W. Eyton. Antiquities of Shropshire, volume 11, p. 284.

- ^ Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, volume 16, no. 1010.

- ^ Calendar of Close Rolls 1389–1392, p. 238.

- ^ a b c d e f Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). Shropshire. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Cokayne, volume 7, p. 359.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1385–1389, p. 327.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 409.

- ^ a b Roskell, J. S.; Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). BURGH, Hugh (d.1430), of Wattlesborough, Salop and Dinas Mawddwy, Merion. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Calendar of Close Rolls, 1413–1419, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Cokayne, volume 2, p. 83.

- ^ Skillington, p. 79-80.

- ^ Wareham and Wright, note anchor 112.

- ^ Calendar of Close Rolls, 1399–1402, p. 144.

- ^ Calendar of Close Rolls, 1402–1405, p. 71.

- ^ Registrum Roberti Mascall, p. 176.

- ^ Baggs et al, Holdgate, note anchor 269.

- ^ Baggs et al. Holdgate, note anchor 279.

- ^ a b c Martin, p. 230.

- ^ D. C. Cox; J. R. Edwards; R. C. Hill; Ann J Kettle; R. Perren; Trevor Rowley; P. A. Stamper (1989). "Domesday Book: 1300–1540". In Baugh, G. C.; Elrington, C. R. (eds.). A History of the County of Shropshire. Vol. 4. note anchor 46 – via British History Online..

- ^ Calendar of Inquisitions Miscellaneous (Chancery), 1392–1399, no. 236, p. 114.

- ^ a b Baggs et al. Shipton, note anchor 247.

- ^ Leighton (1884), p. 258.

- ^ Welsh Deeds, p. 43. in Archaeologia Cambrensis, volume 3, series 2.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1391–1396, p. 548.

- ^ Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). YOUNG, (YONGE), Thomas I, of Sibdon Carwood, Salop. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). HOLBACHE, David (d.c.1422), of Dudleston and Oswestry, Salop. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1391–1396, p. 441.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1391–1396, p. 728.

- ^ Shropshire Archives Document Reference: 3365/67/47 at Discovering Shropshire's History.

- ^ Shropshire Archives Document Reference: 3365/67/47v at Discovering Shropshire's History.

- ^ a b Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1396–1399, p. 318.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1401–1405, p. 100.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1401–1405, p. 352.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1396–1399, p. 435.

- ^ Adam of Usk, p. 25-6.

- ^ Adam of Usk, p. 175.

- ^ a b c Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). CORBET, Robert (1383–1420), of Moreton Corbet, Salop. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1399–1401, p. 563.

- ^ Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). CHEYNE, Sir Hugh (d.1404), of Cheyney Longville, Salop. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). HAWKSTONE, George, of Hawkstone, Salop. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). DARRAS, John (c.1355–1408), of Sidbury and Neenton, Salop. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). PESHALE, Sir Adam (d.1419), of Peshale and Shifnal, Salop, and Weston-under-Lizard, Staffs. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1399–1401, p. 554.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1401–1405, p. 127.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1401–1405, p. 126.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1401–1405, p. 200.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1401–1405, p. 195.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1401–1405, p. 426.

- ^ Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). WILTSHIRE, John, of Arundel and Lyminster, Suss. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1399–1401, p. 414.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1399–1401, p. 416-7.

- ^ Rawcliffe, C. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). SHARESHULL, Sir William (d.1400), of Patshull, Staffs. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1401–1405, p. 364.

- ^ Calendar of Close Rolls, 1389–1392, p. 142.

- ^ Rotuli Parliamentorum, p. 377.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1401–1405, p. 507.

- ^ Calendar of Close Rolls, 1402–1405, p. 479.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 6.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 147.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 156.

- ^ Proceedings and Ordinances of the Privy Council, volume 2, p. 99.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry IV, Volume 3, p. 341.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry IV, Volume 3, p. 352.

- ^ Heale, Martin. "Prestbury, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/107122. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Coulton, p. 9.

- ^ Coulton, p. 10.

- ^ Angold et al, note anchor 51.

- ^ Angold et al, note anchor 2.

- ^ Leighton (1879), p. 198.

- ^ Leighton (1879), p. 206.

- ^ Leighton (1879), p. 204.

- ^ a b Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). LACON, Richard (d.c.1446), of Lacon and Willey, Salop. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 342-3.

- ^ Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). WAKEHURST, Richard (d.1455), of Wakehurst in Ardingley, Suss. and Ockley, Surr. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Rymer's Foedera, July–December 1411, September 1–3.

- ^ Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). GERARD, Nicholas (d.1421), of Shrewsbury, Salop. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). ST. PIERRE, Urian (d.1436), of Shrewsbury, Salop. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1408–1413, p. 466.

- ^ a b c Baggs et al. Munslow, note anchor 147.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 319-20.

- ^ Registrum Johannis Trefnant, p. 181.

- ^ Baggs et al. Munslow, note anchor 357.

- ^ Registrum Roberti Mascall, p. 38-9.

- ^ Registrum Roberti Mascall, p. 47.

- ^ Registrum Roberti Mascall, p. 175.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 424.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1408–1413, p. 182.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1408–1413, p. 377.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1408–1413, p. 477.

- ^ Fletcher, p. 390.

- ^ Fletcher, p. 395.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 339.

- ^ Corbet, p. 247.

- ^ Fletcher, p. 391-2.

- ^ Barker, p. 31-2.

- ^ Barker, p. 48.

- ^ Baggs et al. Ditton Priors, note anchor 173.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1399–1401, p. 427-8.

- ^ Leland's Itineraries, volume 5, p. 15.

- ^ Shropshire Archives Document Reference: 103/1/5/6 at Discovering Shropshire's History.

- ^ Shropshire Archives Document Reference: 1831/2/31/8 at Discovering Shropshire's History.

- ^ a b Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1413–1416, p. 258.

- ^ Barker, p. 117.

- ^ Barker, p. 215.

- ^ Barker, p. 213.

- ^ a b Roskell, J. S.; Woodger, L. S. (1993). Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L. (eds.). BURLEY, William (d.1458), of Broncroft in Corvedale, Salop. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Martin, p. 231.

- ^ Owen and Blakeway, p. 139.

- ^ Baggs et al. Munslow, footnote 147.

- ^ Visitation of Shropshire, volume 2, p. 466.

References

[edit]- M J Angold; G C Baugh; Marjorie M Chibnall; D C Cox; D T W Price; Margaret Tomlinson; B S Trinder (1973). "Religious Guild: Ludlow, Palmers' Guild". In Gaydon, A. T.; Pugh, R. B. (eds.). A History of the County of Shropshire. Vol. 2. London. Retrieved 1 August 2016 – via British History Online.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cambrian Archaeological Association, ed. (1852). Welsh Deeds, AD 1340–1401. 2. Vol. 3. London: Pickering. pp. 36–45. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) at Internet Archive. - "Archives". Discovering Shropshire's History. Shropshire County Council. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- A P Baggs; G C Baugh; D C Cox; Jessie McFall; P A Stamper (1998). Currie, C. R. J. (ed.). A History of the County of Shropshire. Vol. 10. London. Retrieved 25 July 2016 – via British History Online.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Barker, Juliet (2005). Agincourt (2006 ed.). London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-349-11918-2.

- Capes, William W., ed. (1916). Registrum Johannis Trefnant, Episcopi Herefordensis. Vol. 20. London: Canterbury and York Society. Retrieved 21 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Cokayne, George Edward, ed. (1889). The Complete Peerage. Vol. 2. London: George Bell. Retrieved 25 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Cokayne, George Edward, ed. (1896). The Complete Peerage. Vol. 7. London: George Bell. Retrieved 26 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Corbet, Augusta Elizabeth Brickdale. The Family of Corbet; its Life and Times. Vol. 2. London: St. Catherine Press. Retrieved 31 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Coulton, Barbara (2010). Regime and Religion: Shrewsbury 1400–1700. Little Logaston: Logaston Press. ISBN 978-1-906663-47-6.

- D. C. Cox; J. R. Edwards; R. C. Hill; Ann J Kettle; R. Perren; Trevor Rowley; P. A. Stamper (1989). "Domesday Book: 1300–1540". In Baugh, G. C.; Elrington, C. R. (eds.). A History of the County of Shropshire. Vol. 4. London. Retrieved 21 July 2016 – via British History Online.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Eyton, Robert William (1860). Antiquities of Shropshire. Vol. 11. London: John Russell Smith. Retrieved 21 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Fletcher, W. G. D., ed. (1907). Some proceedings at the Shropshire Assizes, 1414. 3. Vol. 7. Shrewsbury: Adnitt and Naunton. pp. 390–396. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) at Internet Archive. - Hanks, Patrick; Hodges, Flavia; Mills, A. D.; et al., eds. (2002). The Oxford Names Companion (1 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860561-7.

- Heale, Martin. "Prestbury, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/107122. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Leland, John (1910). Toulmin Smith, Lucy (ed.). The Itinerary of John Leland. Vol. 5. London: Bell. Retrieved 21 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Leighton, Stanley, ed. (1879). The Records of the Corporation of Oswestry. 1. Vol. 2. Shrewsbury: Adnitt and Naunton. pp. 183–212. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) at Internet Archive. - Leighton, Stanley, ed. (1884). The Records of the Corporation of Oswestry. 1. Vol. 7. Shrewsbury: Adnitt and Naunton. pp. 239–276. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) at Internet Archive. - Martin, Evelyn H. (1916). Bromcroft and its Owners. 4. Vol. 6. Shrewsbury: Adnitt and Naunton. pp. 223–276. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) at Internet Archive. - Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1922). Calendar of the Close Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Richard II, 1389–1392. Vol. 4. London: HMSO. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1927). Calendar of the Close Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry IV, 1399–1402. Vol. 1. London: HMSO. Retrieved 25 July 2016. at Brigham Young University.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1929). Calendar of the Close Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry IV, 1402–1405. Calendar of close rolls : Henry IV. Vol. 2. London: HMSO. Retrieved 25 July 2016. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1929). Calendar of the Close Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry V, 1413–1419. Vol. 1. London: HMSO. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1897). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Richard II, 1381–1385. Vol. 2. London: HMSO. Retrieved 21 July 2016. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1900). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Richard II, 1381–1385. Vol. 3. London: HMSO. Retrieved 21 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1905). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Richard II, 1391–1396. Vol. 5. London: HMSO. Retrieved 26 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1909). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Richard II, 1396–1399. Vol. 6. London: HMSO. Retrieved 26 July 2016. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1903). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry IV, 1399–1401. Vol. 1. London: HMSO. Retrieved 28 July 2016. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1905). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry IV, 1401–1405. Vol. 2. London: HMSO. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1907). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry IV, 1405–1408. Vol. 3. London: HMSO. Retrieved 21 July 2016. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1909). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry IV, 1408–1413. Vol. 4. London: HMSO. Retrieved 21 July 2016. at Hathi Trust.

- Nicolas, Harris, ed. (1834). Proceedings and Ordinances of the Privy Council of England. Vol. 2. London: HMSO. Retrieved 27 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Owen, Hugh; Blakeway, John Brickdale (1825). A History of Shrewsbury. Vol. 2. London: Harding Leppard. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- Parry, Joseph Henry, ed. (1915). Registrum Johannis Gilbert, Episcopi Herefordensis. Vol. 18. London: Canterbury and York Society. Retrieved 21 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Parry, Joseph Henry, ed. (1918). Registrum Roberti Mascall, Episcopi Herefordensis. Vol. 21. London: Canterbury and York Society. Retrieved 25 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- Public Record Office, ed. (1963). Calendar of Inquisitions Miscellaneous (Chancery), 1392–1399. Vol. 6. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-85115-926-3. Retrieved 30 July 2016. at Hathi Trust.

- Roskell, J. S.; Clark, L.; Rawcliffe, C., eds. (1993). History of the Parliament, 1386–1421: Constituencies. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L., eds. (1993). History of the Parliament, 1386–1421: Members. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Rymer, Thomas, ed. (1739). Rymer's Foedera with Syllabus. Vol. 8. London: Jean Neulme. Retrieved 30 July 2016. at British History Online.

- Skillington, S. H. (1928). Ashby de la Zouch: the Descent of the Manor (PDF). Vol. 15. Leicester. pp. 69–84. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) at Internet Archive. - Strachey, John (ed.). Rotuli Parliamentorum; ut et Petitiones, et Placita in Parliamento. Vol. 4. London. Retrieved 27 July 2016. at Brigham Young University.

- Tresswell, Robert; Vincent, Augustine (1889). Grazebrook, George; Rylands, John Paul (eds.). The visitation of Shropshire, taken in the year 1623. Vol. 2. London: Harleian Society. Retrieved 21 July 2016. at Internet Archive.

- de Usk, Adam (1904). Thompson, Edward Maunde (ed.). Chronicon Adae de Usk (2 ed.). London: Henry Frowde. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- Wareham, A. F.; Wright, A. P. M. (2002). Fulbourn: Manors and other estates. Vol. 10. London: British History Online. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) at Internet Archive.