Josef von Sternberg

Josef von Sternberg | |

|---|---|

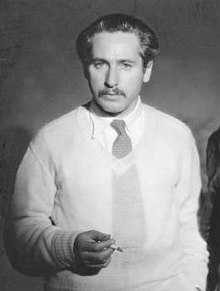

Josef von Sternberg on the set of Dishonored (1931) | |

| Born | Jonas Sternberg May 29, 1894 Vienna, Austria-Hungary (present-day Austria) |

| Died | December 22, 1969 (aged 75) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Years active | 1925–1957 |

| Spouses | Riza Royce (m. 1926; div. 1930)Jean Annette McBride (m. 1945; div. 1947)Meri Otis Wilner (m. 1948) |

| Children | Nicholas Josef von Sternberg |

Josef von Sternberg (German: [ˈjoːzɛf fɔn ˈʃtɛʁnbɛʁk]; born Jonas Sternberg; May 29, 1894 – December 22, 1969) was an Austrian-born filmmaker whose career successfully spanned the transition from the silent to the sound era, during which he worked with most of the major Hollywood studios. He is best known for his film collaboration with actress Marlene Dietrich in the 1930s, including the highly regarded Paramount/UFA production The Blue Angel (1930).[1]

Sternberg's finest works are noteworthy for their striking pictorial compositions, dense décor, chiaroscuro illumination, and relentless camera motion, endowing the scenes with emotional intensity.[2] He is also credited with having initiated the gangster film genre with his silent era movie Underworld (1927).[3][4] Sternberg's themes typically offer the spectacle of an individual's desperate struggle to maintain their personal integrity as they sacrifice themselves for lust or love.[5]

He was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director for Morocco (1930) and Shanghai Express (1932).[6]

Shortly before his death in 1969, his autobiography, Fun in a Chinese Laundry, was published.

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]Josef von Sternberg was born Jonas Sternberg to an impoverished Orthodox Jewish family in Vienna, at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[7] When Sternberg was three years old, his father Moses Sternberg, a former soldier in the army of Austria-Hungary, moved to the United States to seek work. Sternberg's mother, Serafine (née Singer), a circus performer as a child [8] joined Moses in America in 1901 with her five children when Sternberg was seven.[9][10] On his emigration, von Sternberg is quoted as saying, "On our arrival in the New World we were first detained on Ellis Island where the immigration officers inspected us like a herd of cattle."[11] Jonas attended public school until the family, except Moses, returned to Vienna three years later. Throughout his life, Sternberg carried vivid memories of Vienna and nostalgia for some of his "happiest childhood moments."[12][13]

The elder Sternberg insisted upon a rigorous study of the Hebrew language, limiting his son to religious studies on top of his regular schoolwork.[14] Biographer Peter Baxter, citing Sternberg's memoirs, reports that "his parents' relationship was far from happy: his father was a domestic tyrant and his mother eventually fled her home in order to escape his abuse."[15] Sternberg's early struggles, including these "childhood traumas" would inform the "unique subject matter of his films."[16][17][18]

Early career

[edit]In 1908, when Jonas was fourteen, he returned with his mother to Queens, New York, and settled in the United States.[19] He acquired American citizenship in 1908.[20] After a year, he stopped attending Jamaica High School and began working in various occupations, including millinery apprentice, door-to-door trinket salesman and stock clerk at a lace factory.[21] At the Fifth Avenue lace outlet, he became familiar with the ornate textiles with which he would adorn his female stars and embellish his mise-en-scène.[22][23]

In 1911, when he turned seventeen, the now "Josef" Sternberg, became employed at the World Film Company in Fort Lee, New Jersey. There, he "cleaned, patched and coated motion picture stock" – and served evenings as a movie theatre projectionist. In 1914, when the company was purchased by actor and film producer William A. Brady, Sternberg rose to chief assistant, responsible for "writing [inter]titles and editing films to cover lapses in continuity" for which he received his first official film credits.[24][25]

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, he joined the U.S. Army and was assigned to the Signal Corps headquartered in Washington, D.C., where he photographed training films for recruits.[26][23][27]

Shortly after the war, Sternberg left Brady's Fort Lee operation and embarked on a peripatetic existence in America and Europe offering his skills "as cutter, editor, writer and assistant director" to various film studios.[26][23]

Assistant director: 1919–1923

[edit]The Origins of the Sternberg "von"

The nobiliary particle "von" – used to indicate a family descending from nobility – was inserted gratuitously to Sternberg's name on the grounds that it served to achieve an orderly configuration of personnel credits.[28][23] The producer and matinee idol Elliott Dexter suggested the augmentation when Sternberg was assistant director and screenwriter for Roy W. Neill's By Devine Right (1923) in hopes that it would "enhance his screen credit" and add "artistic prestige" to the film.[29]

Director Erich von Stroheim, also from a poor Viennese family and Sternberg's beau idéal, had attached a faux "von" to his professional name. Although Sternberg emphatically denied any foreknowledge of Dexter's largesse, film historian John Baxter maintains that "knowing his respect for Stroheim it is hard to believe that [Sternberg] had no part in the ennobling."[28][30]

Sternberg would ruefully comment that the elitist "von" drew criticism during the 1930s, when his "lack of realist social themes" would be interpreted as anti-egalitarian.[31][32]

Sternberg served his apprenticeship years with early silent filmmakers, including Hugo Ballin, Wallace Worsley, Lawrence C. Windom and Roy William Neill.[33] In 1919, Sternberg worked with director Emile Chautard's on The Mystery of the Yellow Room, for which he received official screen credit as assistant director. Sternberg honored Chautard in his memoirs, recalling the French director's invaluable lessons on photography, film composition and the importance of establishing "the spatial integrity of his images."[34][26] This advice led Sternberg to develop his distinctive "framing" of each shot to become "the screen's greatest master of pictorial composition."[33]

Sternberg's 1919 debut in filmmaking, though in a subordinate capacity, coincided with the filming and/or release of D. W. Griffith's Broken Blossoms, Charlie Chaplin's Sunnyside, Erich von Stroheim's The Devil's Pass Key, Cecil B. DeMille's Male and Female, Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Victor Sjöström's Karin Daughter of Ingmar and Abel Gance's J'accuse.[32]

Sternberg travelled widely in Europe between 1922 and 1924, where he participated in making a number of movies for the short-lived Alliance Film Corporation in London, including The Bohemian Girl (1922). When he returned to California in 1924, he began work on his first Hollywood movie as assistant to director Roy William Neill's Vanity's Price, produced by Film Booking Office (FBO).[35][36] Sternberg's aptitude for effective directing was recognized in his handling of the operating room scene, singled out for special mention by New York Times critic Mordaunt Hall.[37]

United Artists – The Salvation Hunters: 1924

[edit]

The 30-year-old Sternberg made his debut as a director with The Salvation Hunters, an independent picture produced with actor George K. Arthur.[39][40] The picture, filmed on the minuscule budget of $4,800 – "a miracle of organization" – made a tremendous impression on actor-director-producer Charles Chaplin and co-producer Douglas Fairbanks Sr. of United Artists (UA).[41][42] Influenced by the works of Erich von Stroheim, director of Greed (1924), the movie was lauded by cineastes for its "unglamorous realism", depicting three young drifters who struggle to survive in a dystopian landscape.[40][43][44]

Despite its considerable defects, due in part to Sternberg's budgetary constraints, the picture was purchased by United Artists for $20,000 and given a brief distribution, but fared poorly at the box-office.[45]

On the strength of this picture alone, actor-producer Mary Pickford of UA engaged Sternberg to write and direct her next feature. His screenplay, entitled Backwash, was deemed to be too experimental in concept and technique, and the Pickford-Sternberg project was cancelled.[38][46][47]

Sternberg's The Salvation Hunters is "his most explicitly personal work", with the exception of his final picture Anatahan (1953).[48] His distinctive style is already in evidence, both visually and dramatically: veils and nets filter our view of the actors, and "psychological conflict rather than physical action" has the effect of obscuring the motivations of his characters.[49][50]

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer: 1925

[edit]

Released from his contract with United Artists, and regarded as a rising talent in Hollywood, Sternberg was sought after by the major movie studios.[51][52] Signing an eight-film agreement with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1925, Sternberg entered into "the increasingly rigid studio system" at M-G-M, where films were subordinated to market considerations and judged on profitability.[53][54] Sternberg would clash with Metro executives over his approach to filmmaking: the picture as a form of art and the director a visual poet. These conflicting priorities would "doom" their association, as Sternberg "had little interest in making a commercial success."[55][56][57]

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer first assigned Sternberg to adapt author Alden Brooks' novel Escape, retitled The Exquisite Sinner. A romance set in post-World War I Brittany, the movie was withheld from release for failing to clearly set forth its narrative, though M-G-M acknowledged its photographic beauty and artistic merit.[58]

Sternberg was next tasked to direct film stars Mae Murray and Roy D'Arcy in The Masked Bride, both of whom had played in Stroheim's highly acclaimed The Merry Widow (1925). Exasperated with his lack of control over any aspect of the production, Sternberg quit in two weeks – his final gesture turning the camera to the ceiling before walking off the set. Metro arranged a cancellation of his contract in August 1925. Frenchman Robert Florey, Sternberg's assistant director, reported that Sternberg's Stroheim-like histrionics emerged on the M-G-M sets to the consternation of production managers.[46][59][60]

Chaplin and A Woman of the Sea: 1926

[edit]When Sternberg returned from a sojourn in Europe following his disappointing tenure at M-G-M in 1925, Charles Chaplin approached him to direct a comeback vehicle for his erstwhile leading lady, Edna Purviance. Purviance had appeared in dozens of Chaplin's films, but had not had a serious leading role since the much admired picture A Woman of Paris (1923). This would mark the "only occasion that Chaplin entrusted another director with one of his own productions."[61][62]

Chaplin had detected a Dickensian quality in Sternberg's representation of his characters and mise-en-scène in The Salvation Hunters and wished to see the young director expand on these elements in the film. The original title, The Sea Gull, was retitled A Woman of the Sea to invoke the earlier A Woman of Paris.[63]

Chaplin was dismayed by the film Sternberg created with cameraman Paul Ivano, a "highly visual, almost Expressionistic" work, completely lacking in the humanism that he had anticipated.[63] Though Sternberg reshot a number of scenes, Chaplin declined to distribute the picture and the prints were ultimately destroyed.[64][65]

Paramount: 1927–1935

[edit]The failure of Sternberg's promising collaboration with Chaplin was a temporary blow to his professional reputation. In June 1926 he travelled to Berlin at the request of impresario Max Reinhardt to explore an offer to manage stage productions, but discovered he was not suited to the task.[66] Sternberg went to England, where he rendezvoused with Riza Royce, a New York actress originally from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, who had served as an assistant on the ill-fated A Woman of the Sea. They wed on July 6, 1927. Sternberg and Royce would have a tempestuous marriage spanning three years. In August 1928, Riza von Sternberg obtained a divorce from her spouse that included charges of mental and physical abuse, in which Sternberg "seems to have acted a husband's role on the model his [abusive] father provided." The pair remarried in 1928, but the relationship continued to deteriorate, ending in a second and final divorce on June 5, 1931.[67][68]

Silent era: 1927–1929

[edit]In the summer of 1927, Paramount producer B. P. Schulberg offered, and Sternberg accepted, a position as "technical advisor for lighting and photography."[69] Sternberg was tasked with salvaging director Frank Lloyd's Children of Divorce, a movie that the studio executives had written off as "worthless". Working "three [consecutive] days of 20-hour shifts" Sternberg reconceived and reshot half the picture and presented Paramount with "a critical and box-office success."[70] Impressed, Paramount arranged for Sternberg to film a major production based on journalist Ben Hecht's story about Chicago gangsters: Underworld.[71]

This film is arguably regarded as the first "gangster" movie, to the extent that it portrayed a criminal protagonist as tragic hero destined by fate to meet a violent death. In Sternberg's hands the "journalistic observations" provided by Hecht's narrative are abandoned and substituted with a fantasy gangsterland that sprang "solely from Sternberg's imagination."[72][73][74] Underworld, "clinical and Spartan" in its cinematic technique made a significant impression on French filmmakers: Underworld was surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel's favorite film.[75]

With Underworld, Sternberg demonstrated his "commercial potential" to the studios, delivering an enormous box-office hit and Academy Award winner (for Best Original Story). Paramount provided Sternberg with lavish budgets for his next four films.[76] Some historians point to Underworld as the first of Sternberg's accommodations to the studio profit system, whereas others note that the film marks the emergence of Sternberg's distinctive personal style.[77][78]

The movies Sternberg created for Paramount over the next two years – The Last Command (1928), The Drag Net (1928), The Docks of New York (1929) and The Case of Lena Smith (1929), would mark "the most prolific period" of his career and establish him as one of the greatest filmmakers of the late silent era.[79][80][81] Contrary to Paramount's expectations, none were very profitable in distribution.[82][83]

The Last Command earned high praise among critics and added luster to Paramount's prestige. The film had the added benefit of forging collaborative relations between the director and its Academy Award-winning star Emil Jannings and producer Erich Pommer, both temporarily on loan from Paramount's sister studio, UFA in Germany.[84] Before embarking on his next feature, Sternberg, at the studio's behest, agreed to "cut down to manageable length" fellow director Erich von Stroheim's The Wedding March. Sternberg's willingness to accept the assignment had the unhappy side effect of "destroying" his relationship with von Stroheim.[85]

The Drag Net, a lost film, is believed to be a sequel to Underworld.[86] The Docks of New York, "today the most popular of Sternberg's silent films", combines both spectacle and psychology in a romance set in sordid and brutal environs.[87]

Of Sternberg's nine films he completed in the silent era, only four are known to exist today in any archive. That Sternberg's output suffers from "lost film syndrome" makes a comprehensive evaluation of his silent oeuvre impossible.[88][89] Despite this, Sternberg stands as the great "Romantic artist" of this period in film history.[90]

A particularly unfortunate loss is that of The Case of Lena Smith, his last silent movie, and described as "Sternberg's most successful attempt at combining a story of meaning and purpose with his very original style."[91][92] The film fell victim to the emerging talkie enthusiasm and was largely ignored by American critics, but in Europe "its reputation is still high after decades of obscurity."[93][87] The Austrian Film Museum has assembled archival material to reconstruct the film, including a 5-minute print fragment discovered in 2005.[94]

Sound era: 1929–1935

[edit]Paramount moved quickly to adapt Sternberg's next feature, Thunderbolt, for sound release in 1929. An underworld melodrama-musical, its soundtrack employs innovative asynchronous and contrapuntal aural effects, often for comic relief.[95][96] Thunderbolt garnered leading man George Bancroft a Best Actor Award nomination, but Sternberg's future with Paramount was precarious due to the long string of commercial disappointments.[97]

Magnum opus: The Blue Angel: 1930

[edit]

Sternberg was summoned to Berlin by Paramount's sister studio, UFA in 1929 to direct Emil Jannings in his first sound production, The Blue Angel. It would be "the most important film" of Sternberg's career.[100] Sternberg cast the then little-known Marlene Dietrich as Lola Lola, the female lead and nemesis of Jannings character Professor Immanuel Rath, whose passion for the young cabaret singer would reduce him to a "spectacular cuckold."[101] Dietrich became an international star overnight and followed Sternberg to Hollywood to produce six more collaborations at Paramount.[102][103] Film historian Andrew Sarris contends that The Blue Angel is Sternberg's "most brutal and least humorous" work of his oeuvre and yet the one film that the director's "most severe detractors will concede is beyond reproach or ridicule ... The Blue Angel stands up today as Sternberg's most efficient achievement ..."[104]

Sternberg's romantic infatuation with his new star created difficulties on and off the set. Jannings strenuously objected to Sternberg's lavish attention to Dietrich's performance, at the elder actor's expense. Indeed, the "tragic irony of The Blue Angel" was "paralleled in real life by the rise of Dietrich and the fall of Jannings" in their respective careers.[105]

Riza von Sternberg, who accompanied her spouse to Berlin, discerned that director and star were sexually involved. When Dietrich arrived in the United States in April 1930, Mrs. von Sternberg personally presented her with $100,000 libel lawsuits for public remarks made by the star that her marriage was failing, and a $500,000 suit for alienation of [Josef] Sternberg's affections. The Sternberg-Dietrich-Royce scandal was "in and out of the papers", but public awareness of the "ugly scenes" was largely concealed by Paramount executives.[106][107] On June 5, 1931, the divorce was finalized providing $25,000 cash settlement to Mrs. Sternberg and a 5-year annual alimony of $1,200. In March 1932, the now divorced Riza Royce dropped her libel and alienation charges against Dietrich.[108][109]

The Sternberg-Dietrich Hollywood Collaborations: 1930–1935

[edit]Sternberg and Dietrich would unite to make six brilliant and controversial films for Paramount: Morocco (1930), Dishonored (1931), Shanghai Express (1932), Blonde Venus (1932), The Scarlet Empress (1934), and The Devil is a Woman (1935).[110] The stories are typically set in exotic locales including Saharan Africa, World War I Austria, revolutionary China, Imperial Russia, and fin-de-siècle Spain.[111]

Sternberg's "outrageous aestheticism" is on full display in these richly stylized works, both in technique and scenario. The actors in various guises represent figures from Sternberg's "emotional biography", the wellspring for his poetic dreamscapes.[112] Sternberg, largely indifferent to the studio publicity or to his movies' commercial success, enjoyed a degree of control over these pictures that permitted him to conceive and execute these works with Dietrich.[113][114]

Morocco (1930) and Dishonored (1931)

[edit]Seeking to capitalize on the immense European success of The Blue Angel, though not yet released to American audiences,[115][116] Paramount launched the Hollywood production of Morocco, an intrigue-romance starring Gary Cooper, Dietrich and Adolphe Menjou. The all-out promotional campaign declared Dietrich "the woman all women want to see", providing a fascinated public with salacious hints about her private life and adding to the star's glamor and notoriety.[117][118] The fan press inserted an erotic component into her collaboration with Sternberg, encouraging Trilby-Svengali analogies. The publicity tended to distract critics from the genuine merits of the five movies that would follow and overshadowing the significance of Sternberg's lifetime cinematic output.[119][120][121][122]

Morocco serves as Sternberg's exploration of Dietrich's aptitude for conveying onscreen his own obsession with "feminine mystique", a mystique that allowed for a sexual interplay blurring the distinction between male and female gender stereotypes. Sternberg demonstrates his fluency in the visual vocabulary of love: Dietrich dresses in drag and kisses a pretty female; Cooper flourishes a ladies' fan and places a rose behind his ear.[123][124] In terms of romantic complexity, Morocco "is Sternberg's Hollywood movie par excellence".[124]

The box-office success of Morocco was such that both Sternberg and Dietrich were awarded with contracts for three more films and generous increases in salary. The film earned Academy Award nominations in four categories.[125][118]

Dishonored, Sternberg's second Hollywood film, featuring Dietrich opposite Victor McLaglen, was completed before Morocco was released.[126] A film of considerable levity but plot-wise one of his slightest works, this espionage-thriller is a sustained romp through the vicissitudes of spy-versus-spy deception and desire.[127][128] The feature closes with the melodramatic military execution of Dietrich's Agent X-27 (based on Dutch spy Mata Hari), the love-struck femme fatale, a scene that balances "gallantry and ghoulishness."[129][130]

Literary contretemps – An American Tragedy: 1931

[edit]Dishonored had not met with the studio's profit expectations at the box-office, and Paramount New York executives were struggling to find a vehicle to commercially exploit the "mystique and glamor" with which they had endowed the Sternberg-Dietrich productions.[131] While Dietrich was visiting her husband, Rudolf Sieber and their daughter Maria Riva in Europe during the winter of 1930–31, Paramount enlisted Sternberg to film an adaption of novelist Theodore Dreiser's novel An American Tragedy.[132]

The production was initially under the direction of preeminent Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein. His socially deterministic filmic treatment of the novel was rejected by Paramount, and Eisenstein withdrew from the project. Already heavily invested financially in the production, the studio authorized a complete revision of the planned feature.[133] While retaining Dreiser's basic plot and dialogue, Sternberg eliminated its contemporary sociological underpinnings to present a tale of a sexually obsessed middle-class youth (Phillips Holmes) whose deceptions lead to the death of a poor factory girl (Sylvia Sidney). Dreiser was outraged at Sternberg's failure to adhere to his themes in the adaptation and sued Paramount to stop distribution of the movie, but lost his case.[134][135]

Images of water abound in the film and serve as a motif signaling Holmes' motivations and fate. The photography by Lee Garmes invested the scenes with a measure of intelligence and added visual polish to the overall production. Sternberg's role as replacement director curbed his artistic investment in the project. As such, the picture bears little resemblance to his other works of that decade. Sternberg expressed indifference to the mixed critical success it received and banished the picture from his oeuvre.[136][137]

When Dietrich returned to Hollywood in April 1931, Sternberg had emerged as a top-ranking director at Paramount and was poised to begin "the richest and most controversial phase of his career." In the next three years he would create four of his greatest films. The first of these was Shanghai Express.[138][110]

Shanghai Express: 1932

[edit]

"[T]hat love can be unconditional is a hard truth for American audiences to accept at any time. Depression era audiences found it especially difficult to appreciate Sternberg's Empire of Desire ruled by Marlene Dietrich. If, in fact, Shanghai Express was successful at all, it was because it was completely misunderstood as a mindless adventure."

Film historian Andrew Sarris – from The Films of Josef von Sternberg (1966)[140]

"This is the Shanghai Express. Everybody must talk like a train."

Josef von Sternberg, when asked why all the actors in the film spoke in an even monotone.[141]

The theme of the work, as in most of Sternberg's films, is "an examination of deception and desire" in a spectacle pitting Dietrich against Clive Brook, a romantic struggle in which neither can satisfactorily prevail.[142] Sternberg strips the denizens of the train, one-by-one, of their carefully crafted masks to reveal their petty or sordid existences. Dietrich's notoriously enigmatic character, Shanghai Lily, transcends precise analysis but reflects Sternberg's own personal involvement with his star and lover.[143] Scriptwriter Jules Furthman famously provided Dietrich with the poignant admission, "It took more than one man to change my name to Shanghai Lily.".[140]

Sternberg honored the former filmmaker and early mentor Émile Chautard by casting him as the bemused Major Lenard.[144][145]

With Shanghai Express, Sternberg exhibits complete mastery over every element of his work: décor, photography, sound and acting. Lee Garmes, who would serve as cinematographer on this suite of films, won an Academy Award, and both Sternberg and the movie were nominated in their categories.[146][6]

Blonde Venus: 1932

[edit]When Sternberg embarked on his next feature, Blonde Venus, Paramount Pictures' finances were in jeopardy. Profits had plummeted due to a decline in theatre attendance among working class moviegoers. Fearing bankruptcy, the New York executives tightened control over Hollywood film content. Dietrich's heretofore forthright portrayals of demi-mondes (Dishonored, Shanghai Express) were suspended in favor of a heroine who embraced a degree of American-style domesticity. Producer B. P. Schulberg was banking on the success of further Sternberg-Dietrich collaborations to help the studio survive the financial downturn.[147][148]

Sternberg's original story for Blonde Venus and the screenplay by Furthman and S.K. Lauren presents a narrative of a fallen woman, with the caveat that she is ultimately forgiven by her long suffering husband. The narrative exhibited the "sordid self-sacrifice" that was de rigueur for Hollywood's top female performers, yet the studio balked at the redemptive denouement.[140] When Sternberg declined to alter the ending, Paramount put the project on hold and threatened the filmmaker with a lawsuit. Dietrich joined Sternberg in defying the New York executives. Minor adjustments were made that satisfied the studio, but Sternberg's compromises would revert to him after the less than stellar critical and box-office success of the movie.[149]

Paramount's toleration of the duo's defiance was conditioned largely by the considerable profits that they were reaping from Shanghai Express, over $3 million in early distribution.[150][151][152]

Blonde Venus opens with the idealized courtship and marriage of Dietrich and mild-mannered chemist Herbert Marshall. Quickly ensconced as a Brooklyn, New York housewife and burdened with an impish son Dickie Moore, she is compelled to make herself a mistress to politico and nightclub gangster Cary Grant when her husband requires expensive medical treatment for radiation exposure. The plot grows increasingly improbable as Dietrich resurrects her theatrical career that takes to exotic locations around the world – with her little boy in tow.[153][154][155]

The movie is ostensibly about the devotion of a mother for her child, a subject that Sternberg uses to dramatize the traumas of his own childhood and his harsh experiences as a transient laborer in his youth.[156][157] With Blonde Venus, Sternberg reached his apogee stylistically. A film of great visual beauty achieved through multiple layers of evocative décor where style displaces and transcends personal characterizations.[158][159] Between the highly episodic narrative, disparate locales, and an unimpressive supporting cast, the movie is frequently dismissed by critics.[160][161] Blonde Venus's "camp" designation is attributable in part to the outrageous and extremely stylized "Hot Voodoo" nightclub sequence. Dietrich, the beauty, assumes the role of the beast and emerges from an ape costume.[162][163][164]

Paramount's expectations for Blonde Venus were out of proportion to realities of declining theatre attendance. Though not an unprofitable picture, the less than robust critical acclaim weakened the studio's commitment to sustaining further Sternberg-Dietrich creations.[165]

At odds with Paramount and their individual contracts nearly expired, Sternberg and Dietrich privately conceived of forming an independent production company in Germany. Studio executives were suspicious when Sternberg offered no objections when Dietrich was scheduled to star in director Rouben Mamoulian's The Song of Songs (1933) in the final weeks of her term. When Dietrich balked at the assignment, Paramount quickly sued her for potential losses. Courtroom testimony revealed that she was preparing to abscond to Berlin to pursue filmmaking with Sternberg. Paramount prevailed in court, and Dietrich was required to remain in Hollywood and complete the film.[166][167] Any hopes for such a venture were dashed when the National Socialists were ushered into power in January 1933 and Sternberg returned to Hollywood in April 1933.[168][169] Abandoning their plans for independent filmmaking, both Sternberg and Dietrich reluctantly signed a two-film contract with the studio on May 9, 1933.[170]

Reacting to Paramount's increasing coolness towards his films and to the general disarray that plagued studio management since 1932, Sternberg prepared to make one of his most monumental movies: The Scarlett Empress, a "relentless excursion into style" that would antagonize Paramount and mark the onset of a distinct phase in his creative output.[171]

The Scarlet Empress: 1934

[edit]

The Scarlet Empress, an historical drama concerning the rise of Catherine the Great of Russia, had been adapted to film on several occasions by American and European directors when Sternberg began organizing the project.[172] In this, his penultimate film starring Dietrich, Sternberg abandoned contemporary America as a subject and contrived a fantastical 18th-century Imperial Russia, "grotesque and spectacular", stupefying contemporary audiences with its stylistic excesses.[173][174]

The narrative follows the rise of the child Sophia "Sophie" Frederica through adolescence to become Empress of Russia, with special emphasis on her sexual awakening and her inexorable sexual and political conquests.[167][175] Sternberg's decision to examine the erotic decadence among 18th-century Russian nobility was partly an attempt to blindside censors, as historical dramas ipso facto were granted a measure of decorum and gravity.[176][177] The sheer sumptuousness of the sets and décor obscure the allegorical nature of the film: the transformation of the director and star into pawns controlled by the corporate powers that exalt ambition and wealth, "a nightmare vision of the American dream."[178][179]

The film portrays 18th-century Russian nobility as developmentally arrested and sexually infantile, a disturbed and grotesque portrayal of Sternberg's own childhood experiences, linking eroticism and sadism. The opening sequence examines the young Sophia (later Catherine II) early sexual awareness, conflating eroticism and torture, that serves as a harbinger of the sadism that she will indulge in as an empress.[180] Whereas Blonde Venus portrayed Dietrich as a candidate for mother love, the maternal figures in The Scarlet Empress make a mockery of any pretense to such idealizations.[167] Dietrich is reduced to a fantastic and helpless clothes horse, bereft of any dramatic function.[181]

Despite withholding distribution of the film for eight months, so as not to compete with the recently issued United Artists film The Rise of Catherine the Great (1934), starring Elisabeth Bergner, the movie was dismissed by critics and the public. Americans, preoccupied with the challenges of the financial crisis were in no mood for a picture that appeared to be an exercise in self-indulgence.[149][182][175] The film's conspicuous failure among moviegoers was a blow to Sternberg's professional reputation, recalling his 1926 disaster, A Woman of the Sea.[182][183]

Sternberg embarked on the final film of his contract knowing that he was finished at Paramount. The studio was undergoing a realignment in management that was the fall of producer Schulberg, a Sternberg stalwart, and the rise of Ernst Lubitsch, which did not bode well for the director.[184][185] As his personal relationship with Dietrich deteriorated, the studio made clear that her professional career would proceed independently of his. With the cynical blessing of incoming production manager Ernst Lubitsch, Sternberg was given full control over what would be his final film with Marlene Dietrich: The Devil is a Woman.[186]

The Devil is a Woman: 1935

[edit]The Devil is a Woman is Sternberg's cinematic tribute and confession to his collaborator and muse Marlene Dietrich. In this final tribute he sets forth his reflections on their five-year professional and personal association.[187][188]

His key thematic preoccupation is fully articulate here: the spectacle of an individual's conspicuous loss of prestige and authority as the price demanded for surrendering to a sexual obsession.[189] To this endeavor Sternberg brought to bear all the sophisticated filmic elements at his disposal. Sternberg's official handling of the photography is a measure of this.[190][175][191]

Based on a novel by Pierre Louÿs, The Woman and the Puppet (1908), the drama unfolds in Spain's famous carnival at the end of the 19th century. A love triangle develops pitting the young revolutionary Antonio (Cesar Romero) against the middle-aged former military officer Don Pasqual (Lionel Atwill) in a contest for the love of the devastatingly beautiful demi-mondaine Concha (Dietrich). Despite the gaiety of the setting, the film has a dark, brooding, reflective quality. The contest ends in a duel where Don Pasqual is wounded, perhaps mortally: the denouement is never made explicit.[192][175]

More so than any of his previous pictures, Sternberg picked a leading man (Atwill) who is the director's double in more than facial appearance: short stature, stern countenance, proud bearing, verbal mannerisms and immaculate attire. Sternberg has effectively stepped from behind the camera to play opposite Dietrich. This deliberate self-portraiture signals that the film is a submerged commentary on the decline of his career in the movie industry as well as his loss of Dietrich as a lover.[193][194] The sharp exchanges between Concha and Pasqual are filled with bitter recriminations.[195] The players do not emote to convey feeling. Rather, Sternberg carefully applies layer upon layer of décor in front of the lens to create a three-dimensional effect. When an actor steps into this pictorial canvas, the most delicate gesture registers emotion. His outstanding control over the visual integrity is the foundation for much of the eloquence and force of Sternberg's cinema.[196][197]

The March 1935 premiere of The Devil is a Woman in Hollywood was accompanied by a press statement from Paramount announcing that Sternberg's contract would not be renewed. The director anticipated his termination with his own declaration before the film's release explicitly severing his professional ties with Dietrich, writing "Miss Dietrich and I have progressed as far as possible ... if we continued, we would get into a pattern that would be harmful to both of us."[198]

Even with better than expected reviews, The Devil is a Woman cost Sternberg his reputation in the film industry.[199] Sternberg would never again enjoy the largesse nor the prestige that had been conferred on him at Paramount.[200]

A postscript to the release of The Devil is a Woman concerns a formal protest issued by the Spanish government protesting the film's purported disparagement of "the Spanish armed forces" and an insult to the character of the Spanish people. The objectionable scenes depict Civil Guards as inept at controlling carnival merrymakers, and a shot of a policeman consuming an alcoholic beverage in a café. Paramount president Adolph Zukor agreed to suppress the picture in the interest of protecting US-Spain trade agreements – and to protect Paramount film distribution in the country.[201]

Columbia Pictures: 1935–1936

[edit]The personnel shakeup that followed bankruptcy at Paramount in 1934 prompted an exodus of talent. Two of the refugees, producer Schulberg and screenwriter Furthman, were picked up by the manager-owner of the Columbia Pictures, Harry Cohn. These two former colleagues sponsored Sternberg's engagement at the low-budget studio for a two-picture contract.[202][198]

Crime and Punishment: 1935

[edit]An adaption of the 19th-century Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment was Sternberg's first project at Columbia, and a mismatch in terms of his aptitudes and interests. Presenting literary masterpieces to the masses was an industry-wide rage during the financially strapped 1930s. As copyrights on these works were generally expired, the studio paid no fees.[203]

Sternberg invested Dostoevsky's work with a measure of style, but any attempt to convey the complexity of the author's character analysis was suspended in favor of a straightforward, albeit suspenseless, detective story.[204][205] However uninspired, Sternberg proved an able craftsman, dispelling some of the myths regarding his eccentricities, and the film proved satisfactory to Columbia.[206][207]

The King Steps Out: 1936

[edit]Columbia had high hopes for Sternberg's next feature, The King Steps Out, starring soprano Grace Moore and based on Fritz Kreisler's operetta Cissy. A comedy of errors concerning Austrian royalty set in Vienna, the production was undermined by personal and professional discord between opera diva and director. Sternberg found himself unable to identify himself with his leading lady or adapt his style to the demands of operetta.[208][209][210] Wishing to distance himself from the fiasco, Sternberg quickly departed Columbia Pictures after the film's completion. The King Steps Out is the only movie that he insisted be expunged from any retrospective of his work.[211]

In the wake of his distressing two-picture sojourn at Columbia Pictures, Sternberg oversaw the construction of a home on his 30-acre (12-hectares) property in the San Fernando Valley north of Hollywood. Designed by architect Richard Neutra, the avant-garde structure was built to the director's specifications, featuring a faux-moat, an eight-foot (2.4 meter) exterior steel wall and bullet-proof windows. The siege-like character of this desert retreat reflected Sternberg's apprehensions regarding his professional career, as well as his mania to assert strict control over his identity.[212][213]

From 1935 to 1936, Sternberg travelled extensively in the Far East, cataloging his first impressions for future artistic endeavors. During these excursions he made the acquaintance of Japanese film distributor Nagamasa Kawakita – they would collaborate on Sternberg's final movie in 1953.

In Java Sternberg contracted a life-threatening abdominal infection, requiring his immediate return to Europe for surgery.

London Films – I, Claudius: 1937

[edit]The Epic That Never Was

The Epic That Never Was, a 1966 British Broadcasting Corporation documentary by London Films, directed by Bill Duncalf, attempts to address the making of the unfinished I, Claudius and the reasons for its failure.

The documentary includes interviews with surviving members from the cast and crew, as well as director Josef von Sternberg. Contrary to the revised version of the documentary, the Sternberg-Laughton quarrels were not a central factor in the film's undoing. Despite objections from Merle Oberon, the film was not so far advanced in production that she could not be replaced; a substitute actress appears to have been a feasible option.[214]

The material from the final edits would reveal that Sternberg "cut in the camera", i.e. he did not experiment on the set with multiple camera configurations that would provide raw material for the cutting room. On the contrary, he filmed each frame as he wished it to appear on the screen.[215][216][217]

Film historian Andrew Sarris offers this assessment: "Sternberg emerges from the documentary as an undeniable force in the process of creation, and even his enemies confirm his artistic presence in every foot of the film he shot."[140]

While convalescing in London, the 42-year-old director, his creative powers still fully intact, was approached by London Films' Alexander Korda. The British movie impresario asked Sternberg to film novelist and poet Robert Graves's biographical account of Roman Emperor Claudius. Already in pre-production, Marlene Dietrich had intervened on Sternberg's behalf to see that Korda selected her former collaborator rather than the British director William Cameron Menzies.[218]

Claudius as conceived by Graves is "a Sternbergian figure of classic proportions" possessing all the elements for a great film. Played by Charles Laughton, Claudius is an aging, erudite and unwitting successor to the Emperor Caligula. When thrust into power, he initially governs upon the precepts of his heretofore virtuous life. As emperor, he warms to his tasks as a social reformer and military commander. When his young wife, Messalina (Merle Oberon) proves unfaithful while Claudius is away campaigning, he launches his armies against Rome and signs her death warrant. Proclaimed a living god, the now dehumanized and megalomaniacal Claudius meets his tragic fate: to rule his empire utterly alone. The dual themes of virtue corrupted by power, and the cruel paradox that degradation must precede self-empowerment were immensely appealing to Sternberg both personally and artistically.[219][220]

Korda was eager to get the production underway, as Charles Laughton's contract would likely expire during shooting.[221]

Korda had already assembled a talented cast and crew when Sternberg assumed his directorial duties in January 1937. The Austrian-American injected a measure of discipline into the London Film's Denham studio, an indication of the seriousness with which Sternberg approached this ambitious project.[222][223] When shooting commenced in mid-February Sternberg, a martinet who was prone to reducing his performers "to mere details of décor", soon clashed with Laughton, London Film's Academy Award-winning star.[224][225]

As a performer, Laughton required the active intervention of the director to consummate a role – "a midwife" according to Korda. Short of this he could be sullen and intransigent.[226]

Sternberg, who had a clear insight cinematically and emotionally as to the Claudius he wished to create, struggled with Laughton in frequent "artistic arguments". Suffering under Sternberg's high-handedness, the actor announced five weeks into the filming that he would be departing London Film when his contract expired on April 21, 1937. Korda, now under pressure to expedite the production, discreetly sounded Sternberg on the film's likely completion date. With only half the picture in the can, an exasperated Sternberg exploded, declaring that he was engaged in an artistic endeavor, not a race to a deadline.[221]

On March 16, with growing personnel animosities and looming cost overruns, actress Merle Oberon was seriously injured in an automobile accident. Though expected to recover quickly, Korda seized upon the mishap as a pretext to terminate what he had concluded was an ill-fated venture.[227][228]

The film negative and prints were placed into storage at Denham Studio and London Films collected sizable insurance compensation.[229] The greatest share of misfortune accrued to Sternberg. The surviving film sequences suggest that I, Claudius might have been a genuinely great work. When production was aborted, Sternberg lost his last opportunity to reassert his status as a top-rung filmmaker.[230][231]

The collapse of the London Film production was not without its impact on Sternberg. He is reported to have checked into Charring Cross Psychiatric Unit in the aftermath of the shoot.[232] Sternberg's persistent desire to find work kept him in Europe from 1937 to 1938.

He approached Czech soprano Jarmila Novotná as to her availability to star in an adaptation of Franz Werfel's The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, but she demurred. Reviving their mutual interest in playwright Luigi Pirandello's Six Characters in Search of an Author, Sternberg and director Max Reinhardt attempted to obtain the rights but the cost was prohibitive.[233]

At the end of 1937, Sternberg arranged for Austrian financing to film a version of Germinal by Émile Zola, successfully acquiring Hilde Krahl and Jean-Louis Barrault for the lead roles. Final preparations were underway when Sternberg collapsed due to a relapse of the illness he had contracted in Java. While he was convalescing in London, Germany invaded Austria and the project had to be abandoned. Sternberg returned to his home in California to recover but found he had developed a chronic heart condition that would plague him for his remaining years.[234]

M-G-M redux: 1938–1939

[edit]In October 1938, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer asked Sternberg to finish up a few scenes for departing French director Julien Duvivier's The Great Waltz. His association with M-G-M twelve years previously had ended in an abrupt departure. After completing that simple assignment, the studio engaged Sternberg for a one-movie contract to direct a largely pre-packaged vehicle for Austrian-born Hedy Lamarr, the recent star of Algiers. Metro was motivated by Sternberg's success with Marlene Dietrich at Paramount, anticipating that he would instill some warmth in Lamarr's screen image.[235][236]

Sternberg worked on New York Cinderella for little more than a week and resigned. The movie was completed by W. S. Van Dyke as I Take This Woman in 1940. The feature was panned by critics.[237][238]

Sternberg returned to the crime drama, a genre he had created in the silent era, in order to fulfill his contract to M-G-M: Sergeant Madden.

Sergeant Madden: 1939

[edit]A paternalistic patrolman (Wallace Beery) rises through the ranks to become sergeant. As father he presides over a blended family of natural and adopted children: a biological son (Alan Curtis) and adopted children (Tom Brown and Laraine Day). After the natural son marries his "sister", he turns to crime and dies in a police shootout, in which Beery participates. The adopted and dutiful son emulates his father to become a good cop and marries his deceased brother's wife.[239]

The film is notable in that the theme and style strongly resemble German films of the post-WWI period. Thematically, the precept that social duty is superior to family loyalty was commonplace in German literature and film. In particular, the spectacle of an adopted son displacing an interior offspring in a test of physical and moral strength thus proves his worth to society. The central conflict in Sergeant Madden recounts the natural son (Curtis) engages in mortal combat with a powerful father (Beery), bears parallels to Sternberg's boyhood struggles with his tyrannical father Moses.[240][241]

Stylistically, Sternberg's film techniques mimic the dark, gray atmosphere of the German Expressionist films of the 1920s. The minor characters in Sergeant Madden appear to have been recruited from the films of F. W. Murnau. Despite some resistance from the bombastic Beery, Sternberg coaxed a relatively restrained performance that recalls Emil Jannings.[242][243]

United Artists redux – 1940–1941

[edit]Sternberg's restrained directorial performance at Metro reassured Hollywood executives and United Artists provided him with the resources to make the last of his classic films: The Shanghai Gesture.[244]

Shanghai Gesture: 1941

[edit]German producer Arnold Pressburger, an early associate of the director, held the rights to a John Colton play entitled The Shanghai Gesture (1926). This "sensational" work surveyed the "decadent and depraved" denizens of a Shanghai brothel and opium den operated by a "Mother Goddam". Colton's lurid tale presented difficulties to adaption in 1940 when strictures imposed by the Hays Office were in full force. Salacious behavior and depictions of drug use, including opium, were forbidden, leading censors to disqualify more than thirty efforts to transfer The Shanghai Gesture to the screen.[245] Veteran screenwriter Jules Furthman with assistance from Karl Vollmöller and Géza Herczeg formulated a bowdlerized version which passed muster. Sternberg made some additions to the scenario and agreed to film it. Paul Ivano, Sternberg's cinematographer on A Woman of the Sea was enlisted as cameraman.[246][247]

To satisfy censors, the story is set in a Shanghai casino, rather than a brothel; the name of the proprietress of the establishment is softened to "Mother Gin-Sling", rather than the impious "Mother Goddam" in the Colton's original. Gin-Sling's half-caste daughter Gene Tierney – the result of a coupling between Gin-Sling and British official Sir Guy Charteris Walter Huston – is the product of European finishing schools rather than a courtesan raised in her mother's whore house. The degradation of daughter who sports the nickname "Poppy" is no less degraded by her privileged upbringing.[246][248]

Sternberg augmented the original story by inserting two compelling characters: Doctor Omar (Victor Mature) and Dixie Pomeroy (Phyllis Brooks). Dr. Omar – "Doctor of Nothing" – is a complacent sybarite impressive only to cynical casino regulars. His scholarly epithet has no more substance than Sternberg's "von" and the director humorously exposes the pretense.[249] The figure of Dixie, a former Brooklyn chorus girl contrasts with Tierney's continental beauty and this all-American commoner takes the measure of the banal Omar. Poppy, lacking "the humor, intelligence and an appreciation of the absurd" succumbs to the voluptuous Omar – and Sternberg cinematically reveals the absurdity of the relationship.

The veiled parental confrontation between Charteris and Gin-Sling revives only past humiliations and suffering, and Poppy is sacrificed on the altar of this heartless union. Charteris obsessive rectitude blinds him to the terrible irony of his daughter's murder.[250]

The Shanghai Gesture is a tour-de-force with Sternberg's sheer "physical expressiveness" of his characters that conveys both emotion and motivation. In Freudian terms, the gestures serve as symbols of "impotence, castration, onanism and transvestism" revealing Sternberg's obsession with the human condition.[251]

Department of War Information – "The American Scene": 1943–1945

[edit]On July 29, 1943, the 49-year-old Sternberg married Jeanne Annette McBride, his 21-year-old administrative assistant at his home in North Hollywood in a private ceremony.[252]

The Town: 1943

[edit]In the midst of World War II, Sternberg, in a civilian capacity, was asked by the United States Office of War Information to make a single film, a one-reel documentary for the series entitled The American Scene, a domestic version of the combat and recruitment oriented Why We Fight. Whereas his service with the Signal Corps in World War I included filming shorts demonstrating the proper use of fixed bayonets, this 11-minute documentary The Town is a portrait of a small American community in the Midwest with emphasis on the cultural contributions of its European immigrants.[253][254][255][256]

Aesthetically, this short documentary exhibits none of Sternberg's typical stylistic elements. In this respect it is the only purely realistic work he ever created. It is executed, nonetheless, with perfect ease and efficiency, and his "sense of composition and continuity" is strikingly executed. The Town was translated into 32 languages and distributed overseas in 1945.[257][258][259]

At the end of the war, Sternberg was hired by producer David O. Selznick, an admirer of the director, to serve as a roving advisor and assistant on the film Duel in the Sun, starring Gregory Peck. Attached to the unit overseen by filmmaker King Vidor, Sternberg pitched into any task he was assigned with alacrity. Sternberg continued to seek a sponsor for a highly personal project entitled The Seven Bad Years, a journey into self-analysis concerning his childhood and its ramifications for his adult life. When no commercial backing materialized, Sternberg abandoned hopes for support from Hollywood and returned to his home in Weehawken, New Jersey, in 1947.[260]

RKO Pictures: 1949–1952

[edit]For two years Sternberg resided at Weehawken, unemployed and in semi-retirement. He married Meri Otis Wilmer in 1948 and soon had a child and a family to support.[261]

In 1949, screenwriter Jules Furthman, now a co-producer for Howard Hughes' RKO studios in Hollywood, nominated Sternberg to film a color feature. Oddly, Hughes demanded a film test from the 55-year-old director. Sternberg dutifully submitted a demonstration of his skills and RKO, satisfied, presented him with a two-picture contract. In 1950, he began filming the Cold War-era Jet Pilot.[262]

Jet Pilot: 1951

[edit]

As a precondition, Sternberg agreed to deliver a conventional movie that focused on aviation themes and hardware, avoiding the erotic embellishments he was famous for.[263] In a Furthman script that resembled a comic-book narrative, a Soviet pilot-spy Janet Leigh lands her Mig fighter at a USAF base in Alaska, posing as defector. Suspicious, the base commander assigns American pilot John Wayne to play counter-spy. Mutual respect leads to love between the two aviators and when Leigh is denied asylum, Wayne weds her to avoid Leigh's deportation. The USAF sends them to Russia to spread fraudulent intelligence, but upon his return to the air base Wayne is suspected of acting as a double agent and scheduled for brainwashing. Leigh arranges for their escape to Austria.[264]

Janet Leigh is placed at the visual center of the film. She is permitted a measure of eroticism that contrasts sharply and humorously with the All-American pretensions of the Furthman script.[265][266] Sternberg stealthily inserted some subversive elements in this paean of cold war militarism. During the airborne refueling scenes (anticipating Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove), the fighter jets take on the persona and attributes of Leigh and Wayne.[267]

Sternberg wrapped up shooting in merely seven weeks, but the picture was fated to undergo innumerable permutations until it finally enjoyed distribution – and a moderate commercial success – by Universal Studios six years later in September 1957.[268]

With Jet Pilot completed, Sternberg immediately turned to his second film for RKO: Macao.

Macao: 1952

[edit]To Sternberg's discomfiture, RKO maintained strict control when filming commenced in September 1950. The thriller is set in the exotic locale of Macao, at the time a Portuguese colony on the coast of China. American drifters Robert Mitchum and gold-digger Jane Russell become involved in an intrigue to lure corrupt casino owner and jewel smuggler Brad Dexter offshore into international waters so he can be arrested by US lawman William Bendix. Mistaken identities put Mitchum in danger and murders ensue, ending in a dramatic fight scene.[269]

Cinematically, the only evidence that Sternberg directed the picture is where he managed to impose his stylistic signature: a waterfront chase that features hanging fish nets; a feather pillow exploding in an electric fan.[270][271] His handling of the climactic fight between Mitchum and Dexter was deemed deficient by producers. Mastery over action scenes predictably eluded Sternberg and director Nicholas Ray (uncredited) was summoned to re-shoot the sequence in the final stages of production.[272] Contrary to Hughes's inclination to retain Sternberg as a director at RKO, no new contract was forthcoming.

Persevering in his efforts to launch an independent project, Sternberg obtained an option on novelist Shelby Foote's tale of sin and redemption, Follow Me Down, but failed to obtain funding.

Visiting New York in 1951, Sternberg renewed his friendship with Japanese producer Nagamasa Kawakita, and they agreed to pursue a joint production in Japan. From this alliance would emerge Sternberg's most personal film – and his last: The Saga of Anahatan.[273][274]

Later career

[edit]

Between 1959 and 1963, Sternberg taught a course on film aesthetics at the University of California, Los Angeles, based on his own works. His students included undergraduate Jim Morrison and graduate student Ray Manzarek, who went on to form the rock group The Doors shortly after receiving their respective degrees in 1965. The group recorded songs referring to Sternberg, with Manzarek later characterizing Sternberg as "perhaps the greatest single influence on The Doors."[275]

When not working in California, Sternberg lived in a house that he built for himself in Weehawken, New Jersey.[276][277] He collected contemporary art and was also a philatelist, and he developed an interest in the Chinese postal system which led to him studying the Chinese language.[278] He was often a juror at film festivals.[278]

Sternberg wrote an autobiography, Fun in a Chinese Laundry (1965); the title was drawn from an early film comedy. Variety described it as a "bitter reflection on how a master artisan can be ignored and bypassed by an art form to which he had contributed so much."[278] He had a heart attack and was admitted to Midway Hospital Medical Center in Hollywood and died within a week on December 22, 1969, aged 75.[278][279] He was interred in the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Westwood, California near several film studios.[citation needed]

Comments by contemporaries

[edit]Scottish-American screenwriter Aeneas MacKenzie: "To understand what Sternberg is attempting to do, one must first appreciate that he imposes the limitations of the visual upon himself: he refuses to obtain any effect whatsoever save by means of pictorial composition. That is the fundamental distinction between von Sternberg and all other directors. Stage acting he declines, cinema in its conventional aspect he despises as mere mechanics, and dialogue he employs primarily for its value as integrated sound. The screen is his medium – not the camera. His purpose is to reveal the emotional significance of a subject by a series of magnificent canvases".[280]

American film actress and dancer Louise Brooks: "Sternberg, with his detachment, could look at a woman and say 'this is beautiful about her and I'll leave it ... and this is ugly about her and I'll eliminate it'. Take away the bad and leave what is beautiful so she's complete ... He was the greatest director of women that ever, ever was".[281]

American actor Edward Arnold: "It may be true that [von Sternberg] is a destroyer of whatever egotism an actor possesses, and that he crushes the individuality of those he directs in pictures ... the first days filming Crime and Punishment ... I had the feeling through the whole production of the picture that he wanted to break me down ... to destroy my individuality ... Probably anyone working with Sternberg over a long period would become used to his idiosyncrasies. Whatever his methods, he got the best he could out of his actors ... I consider that part of the Inspector General one [of] the best I have ever done in the talkies".[282]

American film critic Andrew Sarris: "Sternberg resisted the heresy of acting autonomy to the very end of his career, and that resistance is very likely one of the reasons his career was foreshortened".[283]

Filmography

[edit]Silent films

[edit]- The Salvation Hunters (1925)

- The Exquisite Sinner (1926, lost)

- A Woman of the Sea (1926, also known as The Sea Gull or Sea Gulls or The Woman who loved once, lost)

- Underworld (1927)

- The Last Command (1928)

- The Dragnet (1928, lost)

- The Docks of New York (1928)

- The Case of Lena Smith (1929, lost)

Sound films

[edit]- Thunderbolt (1929)

- The Blue Angel (1930)

- Morocco (1930)

- Dishonored (1931)

- An American Tragedy (1931)

- Shanghai Express (1932)

- Blonde Venus (1932)

- The Scarlet Empress (1934)

- The Devil is a Woman (1935)

- Crime and Punishment (1935)

- The King Steps Out (1936)

- Sergeant Madden (1939)

- The Shanghai Gesture (1941)

- The Town (1943, short film)

- Macao (1952)

- Anatahan (1953 also known as The Saga of Anatahan)

- Jet Pilot (1957)

Other projects

[edit]- The Masked Bride (1925, directed with Christy Cabanne, uncredited)

- It (1927, directed with Clarence G. Badger, uncredited)

- Children of Divorce (1927, directed with Frank Lloyd, uncredited)

- The Street of Sin (1928, directed with Mauritz Stiller, uncredited)

- I, Claudius (1937, unfinished)

- The Great Waltz (1938, directed with Julien Duvivier, uncredited)

- I Take This Woman (1940, directed with W.S. Van Dyke, uncredited)

- Duel in the Sun (1946, directed with King Vidor, uncredited)

References

[edit]- ^ Sarris, 1998. P. 219

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 8: "The colorful costumes, the dazzling decors, the marble-pillared palaces ..." and p. 6: "His purpose is to reveal the emotional significance of a subject by a series of magnificent canvasses." And Sternberg "relies on long, elaborate shots, each of which is developed internally – by camera movement and dramatic lighting [producing] the effect of emotional percussion." (Sarris quoting Aeneas MacKenzie)

- ^ Weinberg, 1967. P. 34: "... the genre it so eloquently established started a vogue that lasted an entire generation until the outbreak of the Second World War ..."

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 15: "... the first in a tradition" of the [gangster] genre.

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 54: Themes involve "the spectacle of man's dignity and honor crumbling before the assault of desire" bound up with adoration of a woman "which obliterate reason, honor, [and] dignity" and p. 34: the "dilemmas of desire"

- ^ a b Sarris, 1998. p. 499

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 8: "... a poor Orthodox Jewish family ..." and p. 9: "Extract from official [birth] certificate ... christened 'Jonas Sternberg' ..."

- ^ Bach, 1992 p. 98: "...a child circus performer...a tightrope walker in the circus…"

- ^ Bach, 1992 p. 98: Sternberg's birth order.

Baxter, 1971. P. 8: "... when Jonas was three, his father left for the United States ..."

Graves, 1936, in Weinberg, 1967. P. 182: Born in Vienna to "Polish and Hungarian parents." - ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 9: Mother's name is listed on the birth certificate photo.

- ^ Bei unserer Ankuft in der Neuen Welt wir erstes auf Ellis Island interniert, wo die Einwanderungsbeamten uns wie eine Herde Vieh inspiezierten p. 16, Freulein Freiheit by Uli Besel and Uwe Kugelmeyer (Berlin: Transit Buchverlag, 1986)

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 60

- ^ Bach, 1992: p. 98-99: Sternberg "born within sight of the Prater...fed circus horses for pocket money'"

- ^ Baxter, p. 8: His "overbearing" father "denied [Sternberg] all [non-religious] books ..."

- ^ Baxter, 1993. P. 86, 153: "... after each beating [his father Moses] demanded that Jonas kiss the hand that had administered it."

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 22

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 14

- ^ Bach, 1992 p. 99: "The language of the Torah was thrashed into him…his Hebrew schoolmaster no less tyrannical than his father."

- ^ Silver, 2010.

- ^ John Baxter, Von Sternberg, University Press of Kentucky, 2010, p. 15.

- ^ Baxter, 1971 p. 9

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 9

- ^ a b c d Sarris, 1966. P. 5

- ^ Weinberg, 1967. P. 17"... found work as a film-patcher for the [former] World Film Company, gradually working himself up to cutter, writer, assistance director and finally personal manager to William A. Brady of the World Film Company."

- ^ Bach, 1992 p. 99: Sternberg's early employment with Brady

- ^ a b c Baxter, 1971. p. 23

- ^ Weinberg, 1967. P. 17 "... Sternberg joined the [US] Army Signal Corps" in 1917 [when the United States entered WWI], stationed at eh G.H.Q. in Washington, D.C., where he made training films for recruits ... cited for exemplary service."

- ^ a b Baxter, 1971. P. 24-25

- ^ Weinberg, 1967. P. 17-18

- ^ Baxter, 1993. p. 93: "In 1923 Sternberg acquired the implicitly aristocratic 'von' in his credit as assistant director [for] By Divine Right. That part of the gag ... had an implicit association with the name of Erich von Stroheim, another émigré Viennese filmmaker ..."

- ^ Sarris, 1998. P. 212

- ^ a b Sarris, 1966. P. 6

- ^ a b Weinberg, 1967. P. 17

- ^ Sarris, 1966 p. 6

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 24

- ^ Weinberg, 1967. P. 18-19: "Sternberg travelled widely in Europe and the United States. In 1924, Sternberg acted as assistant director to Neill on Vanity's Price at FBO (Film Booking Office) studios in Hollywood, California."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 25-26: see footnote "October 8, 1924" review

- ^ a b Baxter, 1971. p. 31

- ^ Silver, 2010: "... in essence an independent film ..."

- ^ a b Baxter, 1971. p. 26-27

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 10

- ^ Weinberg, 1967. p. 19, p. 22

- ^ Weinberg, 1967. P. 22: "The Salvation Hunters highly praised by artists and critics for its "artistic composition" and "rhythm of presentation"

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 28

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 31

- ^ a b Sarris, 1966. P. 12

- ^ Baxter, 1993. P. 54

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 10, p. 53

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 29-30

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 11

- ^ Weinberg, 1967. P. 24

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 32

- ^ Baxter, 1993. P. 57

- ^ Weinberg, 1967. p. 24

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 7-8

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 32-33

- ^ Weinberg, 1967. p. 25, p. 26-27: Florey declared, based on two reels, that The Masked Bride (had it been completed) "would still be showing today in cine-clubs and film societies everywhere; it was a masterpiece ..."

- ^ Baxter, 1993. P. 55, p. 56

- ^ Baxter, 1993. P. 56

- ^ Weinberg, 1967. P. 25

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 34: "Chaplin had intended a come-back for actress Edna Purviance ..."

- ^ Weinberg, 1967. P. 27

- ^ a b Baxter, 1971. P. 34, 36

- ^ Baxter, 1993. P.111-112

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 13

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 15, p. 34: Sternberg regarded The Sea Gull episode as a "failure" and an "unpleasant experience" and p. 36-37: "... a damaging blow ... depressed by failure."

- ^ Baxter, 1993. p. 77, p. 86: Sternberg "cross as a bear" and "thrown her out of her own home."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 36

- ^ Jeanne and Ford, 1965 in Weinberg, 1967. P. 211

- ^ Wollstein, 1994 p. 148: “...despite some serious flaws, [the film] became pure box-office gold…one of the year’s biggest money-makers” for Paramount.

- ^ Weinberg, 1967. p. 31

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 15:"... the first in a tradition" that is presented from "the point of view of the gangster ..." See also p. 23, p. 66.

Baxter, 1971. p. 43: "opened the door, however selectively, on the reality of modern crime ..."

Wienberg, 1967. P. 34: the film "sets the pattern for the whole cycle of American gangster films." and "... the [gangster] genre ... so eloquently established."

Baxter, 1993. P. 33: "romanticized gangland" movie. - ^ Kehr, Dave. "Underworld," Chicago Reader, accessed October 11, 2010.

- ^ Siegel, Scott, & Siegel, Barbara (2004). The Encyclopedia of Hollywood. 2nd edition. Checkmark Books. p. 178. ISBN 0-8160-4622-0

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 43: "It was to French cinema" that [Sternberg's] filmmaking "left a permanent mark on the art."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 43-44: "Paramount willing to give him anything he wanted."

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 15-16: "Some historians" trace the film to "the beginnings of Sternberg's compromise with Hollywood ... other honor the film ... for stylistic experiments ..."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 43: "... first work to suggest the personal style of later years."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 56

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 16

- ^ Jeanne and Ford, 1965. in Weinberg, 1967. P. 212

- ^ Baxter, 1972. P. 52

- ^ Silver, 2010: "... far and away his most productive period."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 44

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 15-16: When Sternberg "accepted a commission by Paramount Pictures to cut down to manageable length one of Stroheim's best films ... it destroyed their friendship."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 53, p. 54

- ^ a b Baxter, 1971. p. 58

- ^ Silver, 2010. "Of his nine silent films, only four survive. These other works (Underworld, The Last Command, and The Docks of New York) are so good that one must conclude that Sternberg's career, more than that of any other director, suffers from the blight on film history we have come think of as 'lost-film syndrome.'"

- ^ Silver, 2010: "... of the nine films, only four survive."

- ^ Silver, 2010

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 22: "... doubly unfortunate ... more personal ... more unusual" that his recent films.

- ^ Howarth and Omasta, 2007. p. 287

- ^ Howarth and Omasta, 2007. p. 33

- ^ Howarth and Omasta, 2007.

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 23: "Overlooked" by film historians...a "startling experiments" in Soviet school sound techniques using 'asynchronous" methods"employs sound contrapuntally." P. 24: "as much a musical as a melodrama"

- ^ Baxter 1971. P. 61: "Paramount injects a lavish measure of music and comedy"

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 52-53, p. 62

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 75

- ^ Sarris, 1966. p. 25

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 63

- ^ Sarris, 1998. P. 396

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 25

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 72-73

- ^ Sarris, 1998. P. 219-220

- ^ Sarris, 1998. P. 220

- ^ Baxter, 1993. P. 33, p. 40

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 75

- ^ Baxter, 1993. P. 136

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 81

- ^ a b Baxter, 1971. p. 90

- ^ Sarris, 1966. p. 8: "As in a dream [Sternberg] has wandered through studio sets depicting ..." and lists the above locations.

- ^ Sarris, 1966. p. 8: "Sternberg's films [are a] continuous stream of emotional biography ... [his] exoticism ... a pretext of objectifying personal fantasies. ... [his films are a] dream world." p. 25: Sarris quoting Susan Sontag, "The outrageous aestheticism of von Sternberg's six American films with Dietrich ..."

- ^ Baxter, 1993. p. 57-58, p. 90: "... richest and most controversial phase of his career ... a period of three years in which he created a suite [of four] great films, bound together in an agony of frustrated desire."

- ^ Dixon, 2012 p. 2: "Like all of Sternberg's work, [his movies at Paramount were] an entirely personal project over which the director had almost complete control; that the film[s] made money was almost immaterial to the director, though certainly not to Adolph Zukor, the head of Paramount."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 80

- ^ Sarris, 1998. p. 219

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 76

- ^ a b Baxter, 1993. p. 32

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 81: "... the great films [for Paramount] that was to follow [Morocco]."

- ^ Sarris, 1993. p. 210: "Unfortunately, the Svengali-Trilby publicity that enshrouded The Blue Angel [and Sternberg's other collaborations with Dietrich] obscured the more meaningful merits not only of these particular works but Sternberg's career as a whole."

- ^ Baxter, 1993. p. 52: "Paramount's strategy, ever since Dietrich arrived in Hollywood, was to couple the names of Dietrich and Sternberg in their publicity, the one portrayed as Trilby to the other's Svengali, each thus amplifying the other's power to intrigue the public."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 99: "Countless explanations were offered of their relationship, usually in Tribly-Svengali terms ..."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 79

- ^ a b Sarris, 1966. p. 29-30

- ^ Baxter, 1971.p. 76: ... within a few months, in a remarkable elevation to fame, Dietrich was one of Hollywood's most glamorous and controversial stars." See also p.79, p.80

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 82

- ^ Baxter, 1993. p. 82: "... funny and seldom profound ..."

- ^ Sarris, 1966. p. 31: "... Sternberg's funniest film ..."

- ^ Sarris, 1966. P. 32

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 86: "After the mockery and humor of the rest of Dishonored, it is disappointing to see Sternberg, in the climax, fall a victim to the essential seriousness of his intentions ..."

- ^ Baxter, 1993. p. 47: "Thus [Paramount New York headquarters] was already at odds with Hollywood over the best way of making use of these potentially highly profitable collaborators ..."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 86

- ^ Sarris, 1966. p. 33

- ^ Sarris, 1966, p. 32

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 87-88

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 88-89: Sternberg "writes off the film" and is indifference to its fate. And p. 88089: "Of all of Sternberg's Thirties films, An American Tragedy is the one which least resembles his other work." And p. 88-89: "... recurring images of water ... is an apposite parallel ... to motivations."

- ^ Sarris, 1966. p. 34: "recurring water images as stylistic determinates of ... destiny [and] characterization."

- ^ Baxter, 1993. p. 32: "In 1932, no director seemed more suited to [keep] the public going to the movies than Josef von Sternberg" and p. 33: "February 1932 ... Sternberg's position at Paramount's roster of directors ... seemed unassailable."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 99

- ^ a b c d Sarris, 1966. p. 35

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 92

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 94: "The central conflict in Shanghai Express is a stock Sternberg confrontation between destroyer and victim, the two bound together by an interlocking and unexpressed desire for immolation.

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 95-96: Dietrich's characterization of Lily "approaches closest to the core of the Dietrich-Sternberg relationship but, as in the case of the personalities involved, there are no easy answers ... [the imprecision in Sternberg's presentation of Lily] is appropriate to the work of a man whose subject is the woman he loves, but of whose love he is in doubt." And p. 90: "Furthman's ingenuity is vital to the story ... the multiple deceptions that motivate the film, and most of all the enigmatic character of Dietrich's Shanghai Lily." And. p. 97: "... key sequences in which Lily's motivations and extraordinary fabric of her emotions exposed."

- ^ Sarris, 1966. p. 6, p. 34

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 94

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 99: All aspects of filmmaking were "totally at his fingertips ..."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 99-100

- ^ Baxter, 1993. p. 46-47: Executives expressed concern "over the appropriate vehicle for the next Sternberg-Dietrich collaboration" viewing the pair as "potentially highly profitable ..." p. 48: "The home office, however, continued to be concerned that the next project should present a heroine more sympathetic than the prostitute's Dietrich had portrayed in Dishonored and Shanghai Express, and also that the film should have an American setting in order to have a more immediate appeal to domestic audiences."

- ^ a b Baxter, 1993. p. 189

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 100

- ^ Baxter, 1993. p. 46: "Shanghai Express ... the most profitable film yet made by Sternberg."

- ^ Sarris, 1998. p. 228

- ^ Sarris, 1966. p. 36

- ^ Baxter, 1993. p. 173, p. 177: "... the plot [is] over-familiar and improbable ..."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 103: "... the story's growing improbability."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 102: "... a strong thread of autobiography in the film ..." and p. 108

- ^ Sarris, 1966. p. 35-36

- ^ Sarris, 1966. p. 37: "As for Dietrich's rise and fall in Blonde Venus, Sternberg's point is that what Marlene lacks in character she more than makes up for in style, and genuine style can never be dragged through dirt indefinitely."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 109

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 102

- ^ Sarris, 1966. p. 36-37

- ^ Sarris, 1966. p. 25: "... camp ..." And p. 36: "... her nightclub numbers are utterly unmotivated in terms of the plot is a key to the extreme stylization of Dietrich's character, extreme, that is, even for Sternberg."

- ^ Baxter, 1993. p. 164-165

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 105-106

- ^ Baxter, 1993. p. 174: "... Paramount had been banking on Blonde Venus having a success comparable to Shanghai Express." And p. 175: "... not by any means a box-office failure." And p. 176: "Blonde Venus might have been thought a reasonably successful film, but recriminations [among executives] began to fly." p. 176: "Blonde Venus broke the [formerly successful] pattern of Sternberg's films with Dietrich at Paramount [changing] the course of his creative career."

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 110

- ^ a b c Baxter, 1993. p. 188

- ^ Baxter, 1971. p. 111

- ^ Baxter, 1993. p. 188-189

- ^ Baxter, 1971. P. 111: "Schulberg's suspicion at [Sternberg's] tractability matured a few weeks later when Dietrich announce suddenly that she would not appear in The Song of Songs. ... [and the courts] issued an order to keep her in America [to fulfill her contract]."