Kivu conflict

| Kivu conflict | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the aftermath of the Second Congo War | |||||||||

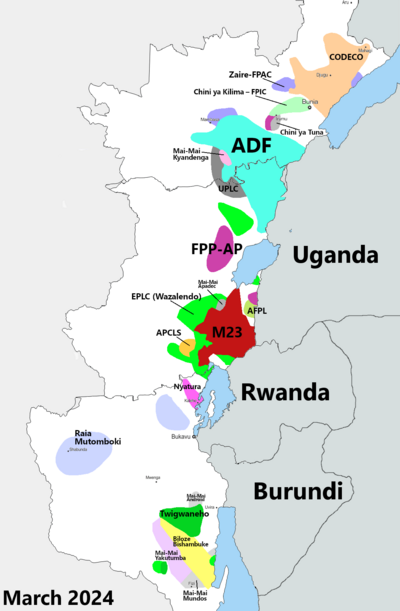

Approximate map of current military situation in Kivu. For a detailed map, see here. Clashes and incidents map:[1] | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents (see full list) | |||||||||

| Supported by: | |

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 6,000–8,000 CNDP (2007)[14] 5,500+ M23 (2012) | 2004: 20,000 total troops;[14] 2008: 2013: 22,016 UN Monusco Uniformed personnel (2013)[16] | 2,000 FDLR[17] 1,500 ACPLS[18] 3,000 FNL/Palipehutu Hundreds of FNL–Nzabampema | Several thousand Raia Mutomboki militia 10,000+ other armed groups | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| CNDP: 233 killed[citation needed] | FARDC: 71 killed[citation needed] BDF: Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| More than 1.4 million internally displaced persons,[22] hundreds of thousands of excess deaths, 11,873+ people killed (including civilians and combatants of each sides)[23][24][20][25][26] | |||||||||

The Kivu conflict is an umbrella term for a series of protracted armed conflicts in the North Kivu and South Kivu provinces in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo which have occurred since the end of the Second Congo War. Including neighboring Ituri province, there are more than 120 different armed groups active in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Currently, some of the most active rebel groups include the Allied Democratic Forces, the Cooperative for the Development of the Congo, the March 23 Movement, and many local Mai Mai militias.[27] In addition to rebel groups and the governmental FARDC troops, a number of national and international organizations have intervened militarily in the conflict, including the United Nations force known as MONUSCO, and an East African Community regional force.

Conflict began in 2004 in the eastern Congo as an armed conflict between the military of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC) and the Hutu Power group Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It has broadly consisted of three phases, the third of which is an ongoing conflict. Prior to March 2009, the main combatant group against the FARDC was the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP). Following the cessation of hostilities between these two forces, rebel Tutsi forces, formerly under the command of Laurent Nkunda, became the dominant opposition to the government forces.

The United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO) has played a large role in the conflict. With 21,000 soldiers in the force, the Kivu conflict constitutes the largest peacekeeping mission currently in operation. In total, 93 peacekeepers have died in the region, with 15 dying in a large-scale attack by the Allied Democratic Forces, in North Kivu in December 2017.[28] The peacekeeping force seeks to prevent escalation of force in the conflict, and minimise human rights abuses like sexual assault and the use of child soldiers in the conflict.[29]

CNDP was sympathetic to the Banyamulenge in Eastern Congo, an ethnic Tutsi group, and to the Tutsi-dominated government of neighboring Rwanda. It was opposed by the FDLR, by the FARDC, and by United Nations forces.

In July 2024, a United Nations report pointed to Uganda's links with the M23[30] and accused the Democratic Republic of Congo of having started in july 2023 arming others groups opposed to M23,[31]. M23 and others groups are engaged in a wide range of abuses in the region: recruitment of child soldiers,[32] violences against the civilian population,[33] looting, illegal mining and corruption.

Background

[edit]Laurent Nkunda was an officer in the rebel Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD), Goma faction in the Second Congo War (1998–2002). The rebel group, backed by Rwanda, was seeking to overthrow then Congolese president Laurent-Désiré Kabila.[34] In 2003, when that war officially ended, Nkunda joined the new integrated national army of the transitional government of Congo as a colonel and was promoted to general in 2004. He soon rejected the authority of the government and retreated with some of RCD-Goma troops to the Masisi forests in Nord Kivu.[35]

Global Witness says that Western companies sourcing minerals were buying them from traders who finance both rebel and government troops. Minerals such as cassiterite, gold, or coltan, which is used for electronic equipment and cell phones, are an important export for the Congo. A UN resolution stated that anyone supporting illegal Congolese armed groups through illicit trade of natural resources should be subjected to sanctions including travel restrictions and an assets freeze.[36] The extent of the problem is not known.[37]

History

[edit]

FDLR insurgency

[edit]The FDLR counts among its number the original members of the Interahamwe that led the 1994 Rwandan genocide. It received extensive backing from, and cooperation from, the government of Congolese President Laurent-Désiré Kabila, who used the FDLR as a proxy force against the foreign Rwandan armies operating in the country, in particular the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPF military wing) and Rwanda-backed Rally for Congolese Democracy. In July 2002, FDLR units still in Kinshasa-held territory moved into North and South Kivu. At this time it was thought to have between 15,000 and 20,000 members. Even after the official end of the Second Congo War in 2002, FDLR units continued to attack Tutsi forces both in eastern DRC and across the border into Rwanda, vastly increasing tensions in the region and raising the possibility of another Rwandan offensive into the DRC – what would be their third since 1996. In mid-2004, a number of attacks forced 25,000 Congolese to flee their homes.[citation needed]

2004–2009: Nkunda's CNDP rebellion

[edit]In early 2004, the peace procedure was already starting to unravel in North Kivu. Under the terms of the deal, all belligerents were to join a transitional government and merge their forces into one national army. However, it quickly became clear that not all parties were fully committed to peace. An early sign of this was the defection of three senior Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD) officers – among them Laurent Nkunda – to form a political movement that morphed into the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP) rebellion in July 2006. The region was once again plunged into turmoil, with fighting reaching the intensity of the Second Congo War. Whilst Mai Mai (self-defence militias) were responsible for some of this violence, the struggle between the CNDP and the Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda (FDLR) – the largest Rwandan Hutu group – was at its heart.[38]

2004 Bukavu offensive

[edit]In 2004, Nkunda's forces began clashing with the DRC army in Sud-Kivu and occupied Bukavu for eight days in June 2004, where he was accused of committing war crimes.[39] Nkunda claimed he was attempting to prevent genocide against the Banyamulenge, who are ethnic Tutsi resident in the eastern DRC.[40] This claim was rejected by the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO).[41] Following UN negotiations which secured the withdrawal of Nkunda's troops from Bukavu to the Masisi forests, part of his army split. Led by Colonel Jules Mutebusi, it left for Rwanda.[39] About 150,000 Kinyarwanda-speaking people (of Nkunda's own language group) were reported to have fled from Sud-Kivu to Nord-Kivu in fear of reprisal attacks by the DRC army.[42]

2005 clashes with DRC army

[edit]In 2005, Nkunda called for the overthrow of the government due to its corruption, and increasing numbers of RCD-Goma soldiers deserted the DRC army to join his forces.[43]

2006

[edit]In January 2006, Nkunda's troops clashed with DRC army forces, who had also been accused of war crimes by the MONUC.[44] Further clashes took place during August 2006 around the town of Sake.[45] MONUC, however, refused to arrest Nkunda after an international arrest warrant was issued against him, stating, "Mr Laurent Nkunda does not present a threat to the local population, thus we cannot justify any action against him."[46] As late as June 2006, Nkunda became subject to United Nations Security Council restrictions.[47]

During both the first and second rounds of the contested and violent 2006 general election, Nkunda had said that he would respect the results.[48][49][50] On 25 November, however, a day before the Supreme Court ruled that Joseph Kabila had won the presidential election's second round, Nkunda's forces undertook a sizeable offensive in Sake against the DRC army 11th Brigade,[51] also clashing with MONUC peacekeepers.[52] The attack may not have been related to the election but due to the "killing of a Tutsi civilian who was close to one of the commanders in this group."[53]

The UN called on the DRC government to negotiate with Nkunda, and DRC Interior Minister, General Denis Kalume, was sent to eastern DRC to begin negotiations.[54]

On 7 December 2006, RCD-Goma troops attacked DRC army positions in Nord Kivu. With military assistance from MONUC, the DRC army was reported to have regained their positions, with about 150 RCD-Goma forces having been killed. Approximately 12,000 Congolese civilians have fled the DRC to Kisoro District, Uganda.[55] Also on that day, a rocket fired from the DRC to the Kisoro District, killing seven people.[56]

2007

[edit]In early 2007, the central DRC government attempted to reduce the threat posed by Nkunda by trying to integrate his troops further into the FARDC, the national armed forces, in what was called a 'mixage' process.[57] However, this backfired and it now appears that from about January to August Nkunda controlled five brigades of troops rather than two. On 24 July 2007, the UN peacekeeping head Jean-Marie Guehenno stated, "Mr Nkunda's forces are the single most serious threat to stability in the DR Congo."[58] In early September, Nkunda's forces had a smaller DRC force under siege in Masisi, and MONUC helicopters were ferrying government soldiers to relieve the town. Scores of men were reported killed, and another major conflict was in progress.[59]

On 5 September 2007, after the government FARDC forces claimed they had used a Mil Mi-24 helicopter gunship to kill 80 of Nkunda's rebels, Nkunda called on the government to return to a peace process. "It's the government side who have broken the peace process. We are asking the government to get back on the peace process, because it is the real way to resolve the Congolese problem", he said[60] In September, Nkunda's men "raided ten secondary schools and four primary schools where they took the children by force in order to make them join their ranks." According to United Nations officials, girls were taken as sex slaves, boys were used as fighters, in violation of international law.[61] Following the date of the UN report, thousands more Congolese fled their homes for displaced persons camps.[62]

The government set a 15 October 2007 deadline for Nkunda's troops to begin disarming. This deadline passed without action and, on 17 October, President Joseph Kabila ordered the military to prepare to disarm Nkunda's forces forcibly. Government forces advanced on the Nkunda stronghold of Kitchanga. Thousands of civilians fleeing the fighting between Nkunda and government-allied Mai-Mai around Bunagana arrived in Rutshuru several days later. There were separate reports of government troops engaging units under Nkunda around Bukima, near Bunagana, as well as some refugees fleeing across the border into Uganda. The number of people displaced by the fighting since the beginning of the year was estimated at over 370,000.[63]

In early November 2007, Nkunda's troops captured the town of Nyanzale, about 100 km (62 mi) north of Goma. Three neighbouring villages were also reported captured, and the army outpost abandoned.[64] A government offensive in early December resulted in the capture by the 82nd Brigade of the town of Mushake, overlooking a key road (however, Reuters reports a FARDC integrated brigade, the 14th, took the town).[65] This followed a statement by the United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo that it would be willing to offer artillery support to the government offensive. In a regional conference held in Addis Ababa, the United States, Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda pledged to support the Congolese government and not support "negative forces", widely seen as code for Nkunda's forces.[66]

Nkunda stated on 14 December 2007 that he was open to peace talks.[67] The government called such talks on 20 December to be held from 27 December 2007 to 5 January 2008.[68] These talks were then postponed to be held from 6 to 14 January 2008.[69]

January 2008 peace deal

[edit]Nkunda's group attended the talks, but walked out on 10 January 2008, after an alleged attempted arrest of one of their members.[70] They later returned to the talks.[71] The talks' schedule was extended to last until 21 January 2008,[72] and then to 22 January 2008 as an agreement appeared to be within reach.[73] It was further extended to 23 January 2008 over final disagreements regarding war crimes cases.[74] The peace deal was signed on 23 January 2008 and included provisions for an immediate ceasefire, the phased withdrawal of all rebel forces in North Kivu province, the resettlement of thousands of villagers, and immunity for Nkunda's forces.[75]

The agreement encouraged FARDC and the United Nations to remove FDLR forces from Kivu. Dissatisfaction with progress and lack of resettlement of refugees caused the CNDP forces to declare war on the FDLR and hostilities to resume,[76] including civilian atrocities.[77] Neither the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda nor the Rwandan government took part in the talks, a fact which may hurt the stability of the agreement.[78][79]

Fall 2008 fighting

[edit]On 26 October 2008, Nkunda's rebels seized a major military camp, along with Virunga National Park for use as a base to launch attacks from. This occurred after the peace treaty failed, with the resultant fighting displacing thousands.[80] The park was taken due to its strategic location on a main road leading to the city of Goma. On 27 October riots began around the United Nations compound in Goma, and civilians pelted the building with rocks and threw Molotov cocktails, claiming that the UN forces had done nothing to prevent the rebel advance.[81] The Congolese national army also retreated under pressure from the rebel army in a "major retreat".[81]

Attack helicopters and armoured vehicles of UN peacekeepers (MONUC) were used in an effort to halt the advance of the rebels, who claim to be within 7 miles (11 kilometres) of Goma.[82] Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for DRC Alan Doss explained the necessity of engaging the rebels, stating that "...[the UN] can't allow population centers to be threatened... [the UN] had to engage."[83] On 28 October, rebels and combined government-MONUC troops battled between the Kibumba refugee camp and Rutshuru. Five rockets were fired at a convoy of UN vehicles protecting a road to the territorial capital of Rutshuru, hitting two armoured personnel carriers. The APCs, which contained Indian Army troops, were relatively undamaged, though a Lieutenant Colonel and two other personnel were injured.[84] Rebel forces later captured the town. Meanwhile, civilians continued to riot, at some points pelting retreating Congolese troops with rocks, though UN spokeswoman Sylvie van den Wildenberg stated that the UN has "reinforced [their] presence" in the region.[85]

On 29 October, the rebels declared a unilateral ceasefire as they approached Goma, though they still intended to take the city.[86] That same day a French request for an EU reinforcement of 1,500 troops was refused by several countries and appeared unlikely to materialise; however, the UN forces in place stated they would act to prevent takeovers of population centres.[86][87] Throughout the day the streets of the city were filled with refugees and fleeing troops, including their tanks and other military vehicles.[86] There were also reports of looting and commandeering of cars by Congolese troops.[88] That night the UN Security Council unanimously adopted a non-binding resolution which condemned the recent rebel advance and demanded it be halted.[89] Despite the ceasefire, World Vision workers had to flee to the Rwandan border to work, and shots were still fired. The United States Department of State sent Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Jendayi Frazer as an envoy to the region.[90]

On 30 October, looting and violence by Congolese soldiers, some of them drunk, continued in Goma, though contingents of other troops and paramilitary police attempted to contain the looting by patrolling the streets in pick-up trucks.[91] Nkunda called for direct talks with the Congolese government,[92] also stating that he would take Goma "if there is no ceasefire, no security and no advance in the peace process."[93] On 31 October, Nkunda declared that he would create a "humanitarian aid corridor", a no-fire zone where displaced persons would be allowed back to their homes, given the consent of the United Nations task force in the Congo. Working with the UN forces around Goma, Nkunda hoped to relocate victims of the recent fighting between his CNDP forces and UN peacekeepers. MONUC spokesman Kevin Kennedy stated that MONUC's forces were stretched thin trying to keep peace within and around the city; recent looting by Congolese soldiers had made it harder to do so as incidents arose both within city limits and outside. According to Anneke Van Woudenberg, a Human Rights Watch researcher, more than 20 people were killed overnight in Goma alone. Meanwhile, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice contacted Rwandan President Paul Kagame to discuss a long-term solution.[94] Also, on 31 October, British Foreign Minister David Miliband and French Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner flew to the region, with the intention of stopping in Kinshasa, Goma, and possibly Kigali.[95]

On 6 November, rebels broke the ceasefire and wrested control of another town in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo in clashes with government forces on the eve of a regional summit on the crisis. National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP) rebels seized control of the centre of Nyanzale, an important army base in Nord-Kivu province after government forces fled. Residents reported that rebels had shot dead civilians suspected of supporting pro-government militia.[96]

Angolan involvement

[edit]In November 2008, during the clashes around Goma, a UN source reported that Angolan troops were seen taking part in combat operations alongside government forces. Kinshasa repeatedly denied that foreign troops were on its soil — an assertion echoed by the UN mission, which has 17,000 blue-helmeted peacekeepers on the ground. There is "military cooperation" between Congo and Angola, and that "there are perhaps Angolan (military) instructors in country", according to the UN. Angola, a former Portuguese colony, sided with Kinshasa in the 1998–2003 Second Congo War that erupted when Democratic Republic of Congo was in a massive rebellion.[97]

Capture of Nkunda and peace treaty

[edit]On 22 January 2009, the Rwandan military, during a joint operation with the Congolese Army, captured Nkunda as he fled from DR Congo into neighbouring Rwanda.[98] Rwandan officials have yet to say if he will be handed over to DR Congo, which has issued an international warrant for his arrest.[98] A military spokesperson said Nkunda had been seized after sending three battalions to repel an advance by a joint Congolese-Rwandan force.[99] The force was part of a joint Congolese-Rwandan operation which was launched to hunt Rwandan Hutu militiamen operating in DR Congo.[100] Nkunda is currently being held at an undisclosed location in Rwanda.[101] A Rwandan military spokesman has claimed, however, that Nkunda is being held at Gisenyi, a city in Rubavu district in the Western Province of Rwanda.[102] DR Congo's government suggested his capture would end the activities of one of the country's most feared rebel groups, recently split by a leadership dispute.[103]

With the ending of the joint Rwandan-DRC offensive against Hutu militiamen responsible for the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda, the Kivu conflict effectively ended. On 23 March 2009, the CNDP signed a peace treaty with the government, in which it agreed to become a political party in exchange for the release of its members.

2009–2012

[edit]Over the weekend of 9/10 May 2009, FDLR Rwandan Hutu rebels were blamed for attacks on the villages of Ekingi and Busurungi in Congo's eastern South Kivu province.[104] More than 90 people were killed at Ekingi, including 60 civilians and 30 government troops, and "dozens more" were said to be killed at Busurungi.[104] The FDLR were blamed by the United Nations' Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs; the UN's peacekeeping force, MONUC, and the Congolese Army investigated the attacks.[104] The FDLR had attacked several other villages in the preceding weeks and clashes occurred between FDLR forces and the Congolese Army, during which government forces are reported to have lost men.[105] The most recent attacks had forced a significant number of people from their homes in Busurungi to Hombo, 20 km (12 mi) north.[105] The Congolese Army and MONUC were planning operations in South Kivu to eliminate the FDLR.[105]

On 18 August, three Indian UN soldiers were killed by Mai-Mai rebels in a surprise attack at a MONUSCO base in Kirumba, Nord-Kivu.[106] On 23 October, Mai-Mai rebels attacked a MONUSCO base in Rwindi (30 km or 19 mi north of Kirumba). UN troops killed 8 rebels in the battle.[106]

M23 rebellion

[edit]

In March 2009, the CNDP had signed a peace treaty with the government, in which it agreed to become a political party in exchange for the release of its imprisoned members.[107] In April 2012, former National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP) soldiers mutinied against the government. The mutineers formed a rebel group called the March 23 Movement (M23). Former CNDP commander Bosco Ntaganda, known as "the Terminator" is accused of founding the movement.[108] On 4 April, it was reported that Ntaganda and 300 loyal troops defected from the DRC and clashed with government forces in the Rutshuru region north of Goma.[109] Africa Confidential said on 25 May 2012 that "the revolt now seems to be as much about resisting an attempt by Kinshasa to disrupt CNDP networks in the restive Kivu provinces, a process of which Ntaganda may find himself a casualty."[110]

On 20 November 2012, the M23 took control of Goma after the national army retreated westward. MONUSCO, the United Nations peacekeeping force, watched the takeover without intervening, stating that its mandate allowed it only to protect civilians.[111][112] M23 withdrew from Goma in early December following negotiations with the government and regional powers.[113]

On 24 February 2013, leaders of 11 African nations signed an agreement designed to bring peace to the eastern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo.[114] The M23 rebels were not represented in the deal's negotiations or at the signing.[114] Following disagreements in the M23 about how to react to the peace agreements, M23 political coordinator Jean-Marie Runiga Lugerero, was sacked by its military chief Sultani Makenga.[115] Makenga declared himself interim leader and clashes between those loyal to him and those loyal to Jean-Marie Runiga Lugerero, who is allied with Bosco Ntaganda, have killed ten men and two others were hospitalised.[116]

In March 2013, the United Nations Security Council authorized the deployment of an intervention brigade within MONUSCO to carry out targeted offensive operations, with or without the Congolese national army, against armed groups that threaten peace in eastern DRC.[117] It is the first peacekeeping unit tasked with carrying out offensive operations.[117]

2013: MONUSCO intervention

[edit]

On 28 March 2013, faced with recurrent waves of conflict in eastern DRC threatening the overall stability and development of the country and wider Great Lakes region, the Security Council decided, by its Resolution 2098, to create a specialized "intervention brigade" for an initial period of one year and within the authorized MONUSCO troop ceiling of 19,815. It would consist of three infantry battalions, one artillery and one special force and reconnaissance company and operate under direct command of the MONUSCO Force Commander, with the responsibility of neutralizing armed groups and the objective of contributing to reducing the threat posed by armed groups to state authority and civilian security in eastern DRC and to make space for stabilization activities.

The council also decided that MONUSCO shall strengthen the presence of its military, police and civilian components in eastern DRC and reduce, to the fullest extent possible for the implementation of its mandate, its presence in areas not affected by conflict in particular Kinshasa and in western DRC.[118]

The last batch of the Malawi troops committed to the MONUSCO Force Intervention Brigade arrived in Goma, North Kivu province, on 7 October 2013. They will be part of the 3000- strong force to which Tanzania and South Africa are the other two troop contributing countries.[citation needed]

Since the arrival of its first troops in June 2013, the Intervention Brigade has already gone into action resulting in the withdrawal of M23, 30 kilometres (19 mi) from its initial positions in Kanyaruchinya, on 31 August 2013.[citation needed]

The Intervention Brigade is now at its full strength with the arrival of the Malawi infantry battalion. Tanzania, South Africa and Malawi have been picked for the UN Stabilization Mission in DR Congo (MONUSCO) because of the wide experience they gained in other UN Peacekeeping missions. For instance, 95 percent of the Malawi troops have been already in peacekeeping missions in Kosovo, Liberia, Rwanda, Sudan, and they are well prepared to face any operational challenges.[119]

2015–2016 resurgence

[edit]

In January 2015, it was reported that UN and Congo troops were preparing an offensive on FDLR in the Kivu region, while striking FNL-Nzabampema positions on Eastern Congo on 5 January 2015.[53] Several days earlier an infiltration by an unknown rebel group from Eastern Congo to Burundi left 95 rebels and 2 Burundi soldiers dead.[53]

On 13 January 2015, the Congolese military held a press conference announcing the destruction of four of the 20 militant factions operating in South Kivu. The Raïa Mutomboki armed group will undergo disarmament. A total of 39 rebels were killed and 24 captured since the start of the Sokola 2 operation in October 2014, 55 weapons and large quantities of ammunition were also seized. FARDC casualties amounted to 8 killed and 4 wounded.[120]

On 25 January 2015, 85 Raïa Mutomboki rebels surrendered to the authorities in the town of Mubambiro, North Kivu; the former militants will be gradually integrated into FARDC. Earlier in January, Raïa Mutomboki, founder Nyanderema, approached the town of Luizi with a group of 9 fighters, announcing their abandonment of armed struggle. 24 rifles, 2 grenades and other military equipment was transferred to FARDC during the two incidents.[121]

On 31 January, the DRC troops launched a campaign against the FDLR Hutu rebels.[122] On 13 March 2015, a military spokesman announced that a total of 182 FDLR rebels were killed since the start of the January offensive. Large amounts of weaponry and ammunition were seized, as the army recaptured the towns of Kirumba Kagondo, Kahumiro, Kabwendo, Mugogo, Washing 1 and 2, Kisimba 1, 2 and 3, among other locales.[123]

In January 2016, fighting broke out between the FDLR, ADF and Mai-Mai militias, which resulted in thousands fleeing to surrounding areas in North Kivu's Goma.[124]

Ethnic Mai Mai factions

[edit]Ethnic conflict in Kivu has often involved the Congolese Tutsis known as Banyamulenge, a cattle herding group of Rwandan origin derided as outsiders, and other ethnic groups who consider themselves indigenous. Additionally, neighboring Burundi and Rwanda, who have a thorny relationship, are accused of being involved, with Rwanda accused of training Burundi rebels who have joined with Mai Mai against the Banyamulenge and the Banyamulenge is accused of harboring the RNC, a Rwandan opposition group supported by Burundi.[125] In June 2017, the group, mostly based in South Kivu, called the National People's Coalition for the Sovereignty of Congo (CNPSC) led by William Yakutumba was formed and became the strongest rebel group in the east, even briefly capturing a few strategic towns.[126] The rebel group is one of three alliances of various Mai-Mai militias[127] and has been referred to as the Alliance of Article 64, a reference to Article 64 of the constitution, which says the people have an obligation to fight the efforts of those who seek to take power by force, in reference to President Kabila.[128] Bembe warlord Yakutumba's Mai-Mai Yakutumba is the largest component of the CNPSC and has had friction with the Congolese Tutsis who often make up commanders in army units.[127] In May 2019, Banyamulenge fighters killed a Banyindu traditional chief, Kawaza Nyakwana. Later in 2019, a coalition of militias from the Bembe, Bafuliru and Banyindu are estimated to have burnt more than 100, mostly Banyamulenge, villages and stole tens of thousands of cattle from the largely cattle-herding Banyamulenge. About 200,000 people fled their homes.[125]

Clashes between Hutu militias and militias of other ethnic groups has also been prominent. In 2012, the Congolese army in its attempt to crush the Rwandan backed and Tutsi-dominated CNDP and M23 rebels, empowered and used Hutu groups such as the FDLR and a Hutu dominated Maï Maï Nyatura as proxies in its fight. The Nyatura and FDLR even arbitrarily executed up to 264 mostly Tembo civilians in 2012.[129] In 2015, the army then launched an offensive against the FDLR militia.[130] The FDLR and Nyatura[131] were accused of killing Nande people[130] and of burning their houses.[132] The Nande-dominate UPDI militia, a Nande militia called Mai-Mai Mazembe[133] and a militia dominated by Nyanga people, the "Nduma Defense of Congo" (NDC), also called Maï-Maï Sheka and led by Gédéon Kyungu Mutanga,[134] are accused of attacking Hutus.[135] In North Kivu, in 2017, an alliance of Mai-Mai groups called the National Movement of Revolutionaries (MNR) began attacks in June 2017[136] includes Nande Mai-Mai leaders from groups such as Corps du Christ and Mai-Mai Mazembe.[127] Another alliance of Mai-Mai groups is CMC which brings together Hutu militia Nyatura[127] and are active along the border between North Kivu and South Kivu.[137] In September 2019, the army declared it had killed Sylvestre Mudacumura, head of the FDLR,[138] and in November that year the army declared it had killed Juvenal Musabimana, who had led a splinter group of the FDLR.[139]

2017–2021: ADF and Islamic insurgency

[edit]Approximately 1.7 million were forced to flee their homes in the DR Congo in 2017 as a result of intensified fighting. Ulrika Blom, a relief worker from Norway, has noted the magnitude of the refugee crisis by comparing the numbers to Yemen, Syria, and Iraq.[140]

27 January 2017 — 2017 Crash of two Mi-24 in DR Congo.

On 27 September 2017, fighting erupted in Uvira as anti-government rebels of the CNPSC attempted to capture the city. This was part of an offensive launched in June of the same year.

On 7 December 2017, an attack orchestrated by the Allied Democratic Forces on a UN base in Semuliki in the North Kivu region resulted in the death of at least 15 UN peacekeepers from the MONUSCO mission.[20] This attack drew international criticism, with UN Secretary-General António Guterres describing the incident, the worst altercation involving peacekeepers in recent history, as a "war crime".[140] The assault, in terms of fatalities, was the most severe suffered by peacekeepers since an ambush in Somalia in 1993.[28] The peacekeeping regiment that came under attack was composed of troops from Tanzania. In addition to the peacekeepers, five soldiers from the FARDC were killed in the attack.[141] Analysts felt that the size and scale of the attack was unprecedented, but that it represented another step in the conflict which has been prevalent in the region for many years.[142] The motivation for the attack was unknown, but it was expected to further destabilise the region. The Congolese forces claimed that the Islamist ADF lost 72 militants in the attack, raising the total number of fatalities in excess of 90.[20]

During 2018, ADF carried out numerous attacks to Beni, inflicting high casualties to civilians and government soldiers:

- 23 September 2018, ADF raided the town of Beni, killing at least 16 people, including four government soldiers.[143]

- 21 October 2018, ADF rebels attacked the town of Matete, just north of Beni, resulting in 11 civilians killed and 15 people were kidnapped (ten of which were children ages five to ten years old).[144] This prompted aid workers to suspend efforts to roll back an outbreak of deadly Ebola.

In addition, on 16 December 2018, Maï-Maï militiamen attacked the Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI) warehouse in Beni ahead of 23 December election, security forces repel attackers without suffering casualties.[145] According to the Congo Research Group (a study project at New York University), as of 2018, 134 armed groups are active in North and South Kivu.[146]

On 31 October 2019, the Congolese army launched a large scale offensive against the ADF in the Beni Territory of the North Kivu Province. According to spokesman General Leon Richard Kasonga, "The DRC armed forces launched large-scale operations overnight Wednesday to eradicate all domestic and foreign armed groups that plague the east of the country and destabilize the Great Lakes region." The operation is being carried out by the FARDC without any foreign support.[147] The focus is primarily on the ADF but also other armed groups are being targeted.[148]

On 13 January 2020, the Congolese army raided ADF's headquarters camp, nicknamed "Madina", which is located near Beni. 30 Congolese soldiers were killed and 70 were wounded in the intense battle with ADF. 40 ADF insurgents were also reported killed, including five top commanders. The Congolese army nevertheless captures the camp, but fails to apprehend the target of the raid, ADF leader Musa Baluku.

On 26 May 2020, at least 40 civilians were killed with machetes by the ADF in Ituri province.[149]

On 16 September 2020, the DRC and 70 armed groups active in South Kivu agreed to cease hostilities.[150]

On 20 October 2020, more than 1,300 prisoners escaped from a jail in Beni after an attack claimed by the ISCAP (Islamic State's Central Africa Province).[151]

On 26 October 2020, The Congolese armed forces took control of the headquarters of Burundi rebel group National Forces of Liberation (NFL) after three days of intense fighting. The army also said they fought some members of the National Resistance Council for Democracy (NRCD). Troops killed 27 rebels, seizing arms and ammunition, while three soldiers died in the fighting, with another four wounded. Now the rebels are fleeing toward the forests of Muranvia, Nyaburunda and Kashongo as well as the Nyanzale Rudaga valley.[152]

On 31 December 2020, Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) massacred 25 civilians in the village of Tingwe.[153] On 1 January 2021, the village of Loselose was recaptured by DRC after a battle between Congolese army, supported by UN peacekeepers and ADF. Two Congolese soldiers and 14 Islamist militants were killed, seven Congolese soldiers were wounded.[154]

On 4 January 2021, ADF attacked villages of Tingwe, Mwenda and Nzenga and killed 25 civilians and kidnapped several others. DRC authorities also discovered 21 civilian bodies "in a state of decomposition" in Loselose and Loulo.[155][156][157]

On 4 February 2021, ISIS operatives exchanged fire with Congolese soldiers in the Rwenzori region, on the border between the Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda. Three soldiers were killed and several others were wounded. The other soldiers fled. ISIS operatives seized vehicles, weapons and ammunition.[158]

On 22 February 2021, the Italian ambassador to DR Congo Luca Attanasio, an Italian law enforcement official and a driver were killed in an attack on a UN convoy near the town of Kanyamahoro, 16 kilometers north of Goma.[159]

On 26 February 2021, IS operatives killed at least 35 Congolese soldiers and wounded many more after a Congolese army force approached IS positions in Losilosi, in the Beni region.[160]

On 6 March 2021, IS militants attacked Congolese forces in a village in the Irumu region. During the attack, at least 7 soldiers were killed and the rest fled. IS operative seized weapons and ammunition.[161]

On 31 March 2021, ADF militants linked to ISIS, massacred 23 civilians after attacking a village in the Beni region.[162][163]

On 9 April 2021, two civilians trucks transporting Christian civilians were targeted by ISIL gunfire southeast of Beni. 5 of the passengers were killed. A Congolese soldier was also shot dead in the area on the same day.[164]

On 23 April 2021, Congolese army camps were targeted by ISCAP militants in the Oicha region. One Congolese soldier was killed in the attacks.[165]

On 30 April 2021, president Felix Tshisekedi declared a "state of siege" over the province of North Kivu that went into effect on 6 May. The state of siege will last for 30 days in which the province will be under military rule.[166]

On 5 May 2021, the FARDC attacked and captured the village of Nyabiondo from APCLS. During the fighting a woman was wounded.[167]

On 24 May 2021, ISIS operatives attacked a Congolese army camp near Kanjabai Prison, in the Beni region, about 50 km west of the Congo-Uganda border. Two soldiers were killed in the exchange of fire. ISIS operatives set fire to the camp.[168]

On 29 June 2021, two Congolese soldiers were killed after ISCAP attacked their positions in the Ituri region.[169]

On 29 July 2021, ISCAP militants attack a convoy of Christian civilians on the Ituri-Beni highway, killing one civilians and destroying 6 vehicles.[170]

On 9 August, ISIL forces took control of the villages of Mavivi and Malibungo in the Ituri region, killing at least one Congolese soldier and capturing 3 others.[171]

On 13 September, ISCAP forces attacked a village in the Ituri region, burning down the homes of several Christians and executing at least one Congolese soldier.[172]

2022-2024: M23 resurgence

[edit]From 28 March 2022, the M23 Movement launched a new offensive in North Kivu,[173] allegedly with Rwandan and Ugandan support. The offensive resulted in the displacement of tens of thousands of refugees, while the rebels had been able to capture some territory by June.[174]

Towns and villages on the list of combat activities were; Beni, Kanyabayonga, Rutshuru, Rumangabo, Goma, Walikale, Bannyahe, Rubavu, Sake, Masisi and Bunagana. War broke out in other areas like Nyagatare, Butare, Bukavu, Fizi and Uvira. M23 has to form a governing alliance with the fighting parties. General S. Makenga was the military commander of M23. The number of refugees has doubled, the first groups of refugees have not been resettled.[citation needed]

2024: United Nations experts sound alarm

[edit]This section may be unbalanced towards certain viewpoints. (July 2024) |

A United Nations report published in July 2024 criticizes the proximity[175] of the Democratic Republic of Congo to armed groups such as the FDLR-FOCA or the Wazalendo, who have taken up arms alongside the Congolese national army. An estimated 200[176] such armed groups are accused of looting in a climate of impunity, particularly in Goma,[177] the capital of North Kivu province. Experts are concerned that these alliances may legitimize the criminal activities of these militias,[178] which illegally exploit natural resources (illegal production and taxation of timber and minerals, financing the conflict and undermining legitimate economic activities). Government military officers are often involved in facilitating these illegal activities and looting.[179] The recruitment of child soldiers continues to reach worrying levels.[180] Acts of violence include indiscriminate attacks on civilians, ransom payments,[181] extrajudicial executions, sexual violence and the use of explosive weapons in populated areas. The conflict has already displaced nearly 7 million people.[182]

Human rights abuses

[edit]Child recruitment by the armed groups

[edit]Violence is widespread: "In Masisi 99.1% (897/905) and Kitchanga 50.4% (509/1020) of households reported at least one member subjected to violence. Displacement was reported by 39.0% of households (419/1075) in Kitchanga and 99.8% (903/905) in Masisi," one study found.[183]

Many armed groups participating in the conflict have used children as active combatants. According to the report published [on 23 October 2013], almost 1,000 cases of child recruitment by armed groups were verified by MONUSCO between 1 January 2012 and 31 August 2013, predominantly in the district of North Kivu.[184] The use of child soldiers in the Kivu conflict constitutes another example of the use of child soldiers in the DRC. The UN has asserted that some of the girls being used as belligerents are also subjected to sexual assault, and are treated as sex slaves.[185]

Sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

[edit]The Kivu conflict has created chaos and disorder in the regions of North and South Kivu. MONUSCO believe that widespread sexual assault has been perpetrated against women in this regions by all sides of the conflict, something which the UNHCR has condemned.[186] Incidents have involved the rape and sexual assault of both women and girls, included the incorporation of girls into militia forces as sex slaves. The most publicised example of sexual violence occurred in November 2012 in Minova. Having retreated to the town, FARDC troops conducted systematic rape against the women and girls over a period of three days. This resulted in widespread international condemnation, prompting the Army to begin an investigation in order to prosecute the perpetrators of the sexual assaults.[187] In 2014, the "Minova Trial" was conducted.[188] It was the largest rape tribunal in the nation's history. While the American Bar Association, which had an office in Goma, had identified more than 1,000 potential victims, the official list composed by the UN only had 126, of whom 56 testified at the trial. For reasons of safety, those testifying were forced to hide their faces by donning hoods. In the end, only a few junior officers were convicted. Sexual violence in the region has continued, but by 2015, funding had declined for sanctuaries for the women and protection.[189]

Conflict minerals

[edit]The role of conflict minerals in the conflict is highly debated.[190] Certain NGOs, like the Enough Project, say that the illegal exploitation of minerals is the main cause of the ongoing violence in the Kivus.[191] A United Nations report supported this view. However, many academic and independent researchers (both Congolese and international) challenge this interpretation, arguing that while conflict minerals are undoubtedly one of the many causes of violence in the region, they are most likely not the most significant and impactful one.[192]

The most prominent and prevalent conflict mineral procured in the Kivu districts is gold. Due to its high financial value, rival militias will attack one another for control of the mineral. An investigation into conflict minerals in relation to the Kivu conflict found that "gold is now, as of 2013, the most important conflict mineral in eastern Congo, with at least 12 tons worth roughly $500 million smuggled out of the east every year." These high financial revenues were identified as the primary incentives for the mining and capture of gold. To illustrate this, this study looked at one specific rebel group, determining that "The M23 rebel group has taken over a profitable part of the conflict gold trade in the east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo...It is using revenues from the illicit trade to benefit its leaders and supporters and fund its military campaign by building military alliances and networks with other armed groups that control territory around gold mines and by smuggling gold through Uganda and Burundi. M23 commander Sultani Makenga, who is also allegedly one of the rebels' main recruiters of child soldiers according to the U.N. Group of Experts on Congo, is at the center of the conflict gold efforts."[193]

Role of European arms

[edit]In 2021, the Transnational Institute published a report about the role of the arms trade in displacements, finding that "between 2012 and 2015 Bulgaria exported assault rifles, large-calibre artillery systems, light machine guns, hand-held under-barrel and mounted grenade launchers to the Democratic Republic of Congo's national police and military. [...] Bulgarian weapons were in use in North Kivu in 2017 coinciding with the forced displacement of 523,000 people."[5] Highlighting the role of the military in human rights abuses, they write that FARDC soldiers in North Kivu "possessed Bulgarian-manufactured ARSENAL weaponry that had been exported to the DRC." The UN found the FARDC to have been responsible for at least 20% of the human rights violations it documented in this region.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "DR Congo: suspicion of an alleged recovery of M23 Rubaya". Silent War Journal. 31 August 2014. Archived from the original on 29 January 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ "Rwanda 'protecting M23 DR Congo rebels'". BBC News. 5 June 2014. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ "Susan Rice: the liberal case against her being secretary of state". The Guardian. 13 December 2012. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ "Conflict Minerals, Rebels and Child Soldiers in Congo". YouTube. 22 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2 March 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Smoking guns". Transnational Institute. 28 July 2021. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ "FARDC hunting down APCLS in Masisi, and what about FDLR?". christoph vogel. 4 March 2014. Archived from the original on 17 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ "Activists urge govt to arrest fugitive DRC warlord". News24. 7 January 2015. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ "Mapping armed groups in eastern Congo". Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ "DRC: Who are the Raïa Mutomboki?". 17 July 2013. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ "Rebel troops capture Bukavu and threaten third Congo war - Independent Online Edition > Africa". news.independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 January 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ "'Scores dead' in Burundi clashes". Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ "Reshuffle in the Congolese army – cui bono? - christoph vogel". christoph vogel. 28 September 2014. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ Chris McGreal (5 August 2014). "US tells armed group in DRC to surrender or face 'military option'". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ a b ""Congo rebels call for peace talks" BBC News Africa 2007-12-13". News.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ a b "DR Congo army pushes rebels back" Archived 16 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC News Africa, 14 November 2008.

- ^ "MONUSCO Facts and Figures - United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo". Un.org. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ "Monusco". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Alliance of Patriots for a Free and Sovereign Congo (APCLS)". Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ "Letter dated 20 May 2018 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council" (PDF). 4 June 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Rebels kill 15 peacekeepers in Congo in worst attack on U.N. in recent". Reuters. 8 December 2017. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ Alexandra Johnson (11 October 2017). "The Allied Democratic Forces Attacks Two UN Peacekeepers in the DRC". Center for Security Policy. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ "DR Congo: Stepping up support for two million displaced". Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ "Kivu Conflict". The Polynational War Memorial. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ "Realtime Data (2017)". ACLED. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ "DR Congo: New 'Kivu Security Tracker' Maps Eastern Violence". Human Rights Watch. 7 December 2017. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "ACLED Data (2018)". ACLED. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "What is the latest conflict in the DR Congo about? - Features". Al Jazeera. 21 June 2022. Archived from the original on 14 May 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ a b correspondent, Jason Burke Africa (8 December 2017). "Islamist attack kills at least 15 UN peacekeepers and five soldiers in DRC". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2017 – via www.TheGuardian.com.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Section, United Nations News Service (8 December 2017). "UN News - DR Congo: Over a dozen UN peacekeepers killed in worst attack on 'blue helmets' in recent history". UN News Service Section. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ Zidi, Paulina (8 July 2024). "RDC: le soutien de l'Ouganda aux rebelles du M23 pointé par un nouveau rapport des experts de l'ONU". RFI (in French). Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "Combats. "Tentative désespérée" : la RDC accusée d'armer des milices dans le Nord-Kivu". Courrier International (in French). 4 January 2024. Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ de Blondin, Charles (8 July 2024). "Nord Kivu : un rapport de l'ONU met en lumière les responsabilités RDC et l'Ouganda, jusque-là sous-médiatisées". Contrepoints (in French). Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ Lawson, Philippe (9 July 2024). "Un rapport de l'ONU pointe la responsabilité de la RDC dans le conflit au Nord-Kivu". L-Post (in French). Retrieved 12 July 2024.

- ^ "Profile: Laurent Nkunda, the Tutsi rebel leader toppled from power". Daily Telegraph. 23 January 2009. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ "D.R. Congo: Arrest Laurent Nkunda For War Crimes" Archived 1 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Human Rights Watch News, 2006-02-01

- ^ "Mineral firms fuel Congo unrest" Archived 24 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, July 2009

- ^ Sekyewa, Edward Ronald (12 May 2011). "Trade in Congolese Gold: A dilemma". Kampala Dispatch. Archived from the original on 7 September 2012.

- ^ "Rebellion and Conflict Minerals in North Kivu". ACCORD. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Rebel troops capture Bukavu and threaten third Congo war". The Independent. 3 June 2004. Archived from the original on 10 January 2008.

- ^ "DRC: Interview with rebel general Laurent Nkunda". IRIN. 2 September 2006. Archived from the original on 15 November 2006.

- ^ "DRC: UN preliminary report rules out genocide in Bukavu". IRIN. 17 January 2004. Archived from the original on 9 September 2005.

- ^ "DRC: Government troops seize rebel stronghold, general says". IRIN. 14 September 2004. Archived from the original on 17 March 2006.

- ^ "Nkunda Building Forces: Rebel General Draws on More Deserting Troops". Sobaka. 16 September 2005. Archived from the original on 29 August 2006.

- ^ "DRC: Human rights situation in Feb 2006". reliefweb.int. MONUC. 18 March 2006. Archived from the original on 10 January 2008.

- ^ "Rebel troops clash with army in eastern Congo". SABCnews.com. South African Broadcasting Corporation. 5 August 2006. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- ^ "DRC: No plan to arrest dissident ex-general". IRIN. 23 September 2006. Archived from the original on 29 November 2006.

- ^ "List of individuals and entities subject to the measures imposed by paragraph 13 and 15 of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1596 (2005), pursuant to Resolution 1533 (2004)". UN.org. United Nations Security Council. 6 June 2006. Archived from the original on 10 January 2008.

- ^ "DRC: Interview with Jacqueline Chenard, spokeswoman for MONUC in Kivu North" Archived 30 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine, IRIN, 2006-07-30

- ^ "Congo's rebel leader watches and waits" Archived 14 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Financial Times, 2006-08-07

- ^ "DRC rebel leader commits to peace" Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, SABC, 2006-10-27

- ^ "Congo Warlord's Fighters Attack Forces" Archived 25 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Washington Post, 2006-11-26

- ^ "UN says engages rebels as army flees Congo town" Archived 10 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 2006-11-26

- ^ a b c "UN, Congo Prepare Offensive Against FDLR Rebels". VOAnews.com. Voice of America. 5 January 2015. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ "UN Calls for Negotiations in Eastern DRC" Archived 14 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Voice of America, 2006-11-27

- ^ "DRC: 12,000 Congolese flee into Uganda" Archived 23 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, SomaliNet News, 2006-12-08

- ^ "DRC: Rocket kills 7 in Uganda" Archived 23 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, SomaliNet News, 2006-12-07

- ^ Henri Boshoff "The DDR Process in the DRC: A Never-Ending Story" Archived 16 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Institute for Security Studies, 2007-07-02

- ^ "Rogue general threatens DRC peace" Archived 24 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine BBC News Africa 2007-07-24

- ^ McGreal, Chris (3 September 2007). "Fear of fresh conflict in Congo as renegade general turns guns on government forces". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- ^ "DRC rebel general calls for peace". BBC News. 5 September 2007. Archived from the original on 18 November 2008.

- ^ "Congo warlord continues to recruit kids". Sydney Morning Herald. 20 September 2007. Archived from the original on 10 January 2008 – via smh.com.au.

- ^ "Congolese flee renegade general". BBC News. 23 September 2007. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007.

- ^ "Thousands flee amid Congo clashes". BBC News. 20 October 2007. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007.

- ^ "DR Congo rebels take eastern town". BBC News. 3 December 2007. Archived from the original on 6 December 2007.

- ^ Bavier, Joe (5 December 2007). "Congo army says retakes eastern town from rebels". alertnet.org. Archived from the original on 6 December 2007.

- ^ "Army seizes DR Congo rebel base". BBC News. 5 December 2007. Archived from the original on 7 December 2007.

- ^ "DR Congo rebel 'ready for peace'". BBC News. 14 December 2007. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007.

- ^ "DR Congo invites rebels to talks". BBC News. 20 December 2007. Archived from the original on 20 December 2007.

- ^ Van Den Wildenberg, Sylvie (28 December 2007). "Congo-Kinshasa: Launching of Preparatory Work for Kivus Peace Conference". allafrica.com. United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008.

- ^ "Rebels resume Congo peace talks". BBC. 11 January 2008. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ "Nkunda's team to return to DR Congo peace conference". Agence France-Presse. 10 January 2008. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ "UN-backed summit in DR Congo discusses amnesty for dissident general". UN.org. 18 January 2008. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017.

- ^ "Armed groups in east DR Congo ready for ceasefire". Agence France Press. 21 January 2008. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011.

- ^ "Row over war crimes status delays end of DR Congo conference". Agence France Press. 22 January 2008. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011.

- ^ "Eastern Congo peace deal signed". BBC. 23 January 2008. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ "As Congo Rebels Advance, Civilians Target U.N." All Things Considered. National Public Radio. 27 October 2008. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017.

- ^ "After Two Key Deals, What Progress Towards Peace in North Kivu?". Allafrica.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ "Rebels 'threaten DR Congo deal'". BBC News. 24 January 2008. Archived from the original on 28 January 2008.

- ^ "Is this peace for eastern DR Congo?". BBC News. 24 January 2008. Archived from the original on 27 January 2008.

- ^ "Thousands flee fighting as Congo rebels seize gorilla park". CNN. 26 October 2008. Archived from the original on 27 October 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- ^ a b "Protesters attack U.N. HQ in eastern Congo". CNN. 24 October 2008. Archived from the original on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- ^ "U.N. gunships battle rebels in east Congo". CNN. 28 October 2008. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- ^ "UN joins battle with Congo rebels". BBC. 27 October 2008. Archived from the original on 28 October 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- ^ "Armymen hurt in Congo". The Hindu. 30 October 2008. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- ^ "Thousands flee rebel advance in Congo". CNN. 28 October 2008. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- ^ a b c Philp, Catherine (30 October 2008). "UN peacekeepers braced for full-scale war in central Africa". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ^ Faul, Michelle (29 October 2008). "Congo rebels reach Goma edge, declare cease-fire". Associated Press. Retrieved 29 October 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Gettleman, Jeffrey (29 October 2008). "Many Flee as Congo Rebels Approach Eastern City". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- ^ "Le Conseil de sécurité condamne l'avancée des rebelles dans l'est de la RDC". Le Monde (in French). 30 October 2008. Archived from the original on 2 November 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ^ "Congo rebels declare cease-fire to prevent panic". CNN. 30 October 2008. Archived from the original on 2 November 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ^ Barth, Patrick (31 October 2008). "Drunk and in retreat, troops unleash wave of death on their own people". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ^ "Rebels call for talks in Congo". Belfast Telegraph. 31 October 2008. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ^ Boussen, Yves (31 October 2008). "Congo rebels warn of city occupation". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ^ "Rebel general offers aid corridor for Congo". CNN. 31 October 2008. Archived from the original on 2 November 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- ^ Sturcke, James (1 November 2008). "David Miliband holds talks with Congolese president". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ "Congolese rebels make new gains". BBC News. 6 October 2008. Archived from the original on 9 November 2008. Retrieved 7 October 2008.

- ^ "Congo War". GlobalSecurity.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ a b "Rwanda arrests Congo rebel leader". BBC News. 23 January 2009. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009.

- ^ "Rebel leader General Nkunda arrested". The Zim Daily. 23 January 2009. Archived from the original on 29 January 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ^ "Congo, rebel leader Nkunda arrested". Africa Times. 23 January 2009. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ^ "Congo's Nkunda arrested in Rwanda". RTÉ.ie. RTÉ. 23 January 2009. Archived from the original on 26 January 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ^ "Congo rebel leader Nkunda arrested". el Economista. 23 January 2009. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ^ "Congo rebel leader Nkunda arrested in Rwanda". Khaleej Times. 23 January 2009. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ^ a b c "'Dozens killed' in DR Congo raids". BBC. 13 May 2009. Archived from the original on 16 May 2009. Retrieved 14 May 2009.

- ^ a b c "Dozens of civilians killed in DRCongo rebel attacks: UN". Associated Press. 13 May 2009. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2009.

- ^ a b "UN peacekeepers in DR Congo repel attack". AFP. 25 October 2010. Archived from the original on 10 November 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ "DR Congo government, CNDP rebels 'sign peace deal'" Archived 30 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, AFP, 24 March 2009.

- ^ "DR Congo troops shell rebel bases — Africa". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- ^ "Congo-Kinshasa: General Ntaganda and Loyalists Desert Armed Forces". Allafrica.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ "Rwanda looms larger in Kivu". AC. 25 May 2012.

- ^ Jones, Pete; Smith, David (20 November 2012). "Goma falls to Congo rebels". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 November 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ Hogg, Jonny (20 November 2012). "Congo rebels seize eastern city as U.N. forces look on". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 November 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ "Rebels in DR Congo withdraw from Goma". BBC News. 18 December 2012. Archived from the original on 6 December 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ^ a b "African leaders sign deal aimed at peace in eastern Congo". Reuters. 24 February 2013. Archived from the original on 28 February 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ "DR Congo: Army 'seizes' eastern towns held by M23 rebels". bbcnews.com. 2 March 2013. Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ^ "Clashes among DR Congo rebels leave 10 dead". Global Post. AFP. 25 February 2013. Archived from the original on 25 February 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Tanzanian troops arrive in eastern DR Congo as part of UN intervention brigade". United Nations. 10 May 2013. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ "MONUSCO Mandate - United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo". UN.org. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ "Last batch of Malawi troops now in Goma for the UN Force Intervention Brigade". MONUSCO.unmissions.org. 21 October 2013. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ "Sud-Kivu: 4 des 20 groupes armés "complètement démantelés", selon les FARDC". Radio Okapi. 13 January 2015. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ^ "Sud-Kivu: 85 Raïa Mukombozi se rendent aux FARDC". Radio Okapi. 25 January 2015. Archived from the original on 26 January 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ "DR Congo says offensive against Hutu rebels underway". 31 January 2015. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "Traque contre les FDLR: environ 182 rebelles neutralisés au Nord et Sud-Kivu". Radio Okapi. 13 March 2015. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ "Fighting in eastern DRC forces thousands to flee". News Stories. 29 January 2016. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ a b "In eastern Congo, a local conflict flares as regional tensions rise". The New Humanitarian. 28 October 2019. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ "Eastern Congo rebels aim to march on Kinshasa: spokesman". Reuters. 29 September 2017. Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Inside the Congolese army's campaign of rape and looting in South Kivu". Irinnews. 18 December 2017. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Heavy Fighting in Eastern DR Congo, Threats to Civilians Increase". Human Rights Watch. 4 October 2017. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ "Who are the Nyatura rebels?". IBT. 22 February 2017. Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ a b "At least 21 Hutus killed in 'alarming' east Congo violence: UN". Reuters. 8 February 2016. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Armed groups in eastern DRC". Irin news. 31 October 2013. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "DRC: Rebels kill at least 10 in troubled eastern region". Al Jazeera. 19 July 2016. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Congo rebels kill at least 8 civilians in mounting ethnic violence". Reuters. 8 August 2016. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "27 killed in DRC after Maï-Maï fighters target Hutu civilians in North Kivu". International Business Times. 20 February 2017. Archived from the original on 10 March 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "DR Congo militia attack kills dozens in eastern region". Al Jazeera. 28 November 2016. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Rebellion fears grow in eastern Congo". Irinnews. 31 October 2017. Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ "Sud-Kivu : Les miliciens envahissent les localités abandonnées par l'armée à Kalehe". Actualité (in French). 2 October 2017. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Rwandan Hutu militia commander killed in Congo, army says". Reuters. 18 September 2019. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "Congo army kills leader of splinter Hutu militia group". Reuters. 10 November 2019. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ a b "UN peacekeepers killed in DR Congo". BBC News. 8 December 2017. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "At least 14 UN peacekeepers killed in Congo attack". RTÉ.ie. 8 December 2017. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ Vogel, Christoph (8 December 2017). "Analysis - U.N. peacekeepers were killed in Congo. Here's what we know". Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017 – via WashingtonPost.com.

- ^ "DR Congo: Rebels carry out deadly attack in Beni city". aljazeera.com. 23 September 2018. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Democratic Republic of Congo: Rebels kill 11 people, kidnap 10 children near Beni". thedefensepost.com. AFP. 21 October 2018. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "DRC: Maï-Maï militiamen attack CENI warehouse in Beni Dec. 16 /update 1". garda.com. 18 December 2018. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Kivu: The forgotten war". Mail & Guardian. 26 September 2018. Archived from the original on 18 November 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2021 – via mg.co.za.

- ^ "DR Congo army launches 'large-scale operations' against militias in Beni territory". The Defense Post. 31 October 2019. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019.

- ^ "DR Congo launches large-scale operation against rebels". Al Jazeera. 1 November 2019. Archived from the original on 11 November 2019.

- ^ "At least 40 killed in latest DR Congo massacre | News | al Jazeera". Archived from the original on 13 September 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ "'All' armed groups commit to ceasefire in DRC's South Kivu". Macau Business. 17 September 2020. Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ Ives, Mike; Kwai, Isabella (20 October 2020). "1,300 Prisoners Escape From Congo Jail After an Attack Claimed by ISIS". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "DR Congo army says Burundi rebels forced from strongholds". aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ "DR Congo army says lost two soldiers, killed 14 ADF fighters". aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "Congo Army Says its Forces Recapture Eastern Village From Islamist Group". voanews.com. Voice of America. 2 January 2021. Archived from the original on 9 February 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "Guterres 'shocked' at massacre of civilians in eastern DR Congo". UN.org. 7 January 2021. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "At least 22 civilians killed in rebel attack in eastern DRC". aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "Ugandan rebel group blamed for deaths of 22 people in DRC". iol.co.za. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "Spotlight on Global Jihad (February 4-10, 2021)". 11 February 2021. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "Italian ambassador to DR Congo dies in attack on UN convoy". The Guardian. 22 February 2021. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ "Spotlight on Global Jihad (February 25 – March 3, 2021)". 4 March 2021. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ "Spotlight on Global Jihad (March 4-10, 2021)". 11 March 2021. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ "Suspected ADF rebels kill 23 in eastern DR Congo attack". Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "Suspected ADF Rebels Massacre 23 in DRC". Persecution. April 2021. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "Spotlight on Global Jihad (April 8 – 14, 2021)". 18 April 2021. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Spotlight on Global Jihad (April 22-29, 2021)". 2 May 2021. Archived from the original on 10 September 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "DR Congo declares a 'state of siege' over worsening violence in east". France 24. 1 May 2021. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ "Kivu Security Tracker | Crisis Mapping in Eastern Congo". Kivu Security Tracker | Crisis Mapping in Eastern Congo. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ "Spotlight on Global Jihad (May 19-26, 2021)". 27 May 2021. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Spotlight on Global Jihad (June 24-30, 2021)". July 2021. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Spotlight on Global Jihad (July 29 – August 4, 2021)". The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center. 5 August 2021. Archived from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ "Spotlight on Global Jihad (August 5-11, 2021)". The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center. 12 August 2021. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "Spotlight on Global Jihad (September 14 – October 6, 2021)". The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center. 7 October 2021. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "M23 rebels attack military positions in eastern DR Congo". aljazeera.com. 28 March 2022. Archived from the original on 12 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ Djaffar Sabiti (13 June 2022). "Congo rebels seize eastern border town, local activists say". Reuters. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ "Final report of the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo (S/2024/432)". ReliefWeb. 9 July 2024. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Vespierre, Gérard (11 July 2024). "La République Démocratique du Congo (RDC) va-t-elle créer une guerre régionale ?". La Tribune (in French). Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Pierret, Coralie (15 April 2024). "Dans l'est de la RDC, les revers de l'armée plongent Goma dans l'insécurité". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Agou, Fleury (10 July 2024). "Guerre au Nord Kivu : Rapport de l'ONU sur un conflit oublié". Revue Conflits (in French). Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Baraka, Héritier (11 July 2024). "Militaires condamnés à mort en RDC: la société civile du Nord-Kivu appelle à sanctionner aussi des hauts gradés". RFI (in French). Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Massa, Bastien (18 June 2024). "Dans l'est de la République démocratique du Congo, la difficile démobilisation des enfants soldats du Kivu". Le Figaro (in French). Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Pierret, Coralie (13 December 2023). "Les « wazalendo », des « patriotes » en guerre dans l'est de la RDC". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ "RDC : 6,9 millions de déplacés internes, du jamais-vu selon l'OIM". Le Monde (in French). 30 October 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Alberti, K. P.; Grellety, E.; Lin, Y. C.; Polonsky, J.; Coppens, K.; Encinas, L.; Rodrigue, M. N.; Pedalino, B.; Mondonge, V. (2010). "Violence against civilians and access to health care in North Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo: three cross-sectional surveys". Conflict and Health. 4: 17. doi:10.1186/1752-1505-4-17. PMC 2990729. PMID 21059195.

- ^ "MONUSCO alarmed by child recruitment in DRC". Monusco.unmissions.org. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ Grover, Sonja C. (2012). Humanity S Children: ICC Jurisprudence and the Failure to Address the Genocidal Forcible Transfer of Children (2013 ed.). Springer. p. 117. ISBN 978-3642325007.

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Sexual violence on the rise in DRC's North Kivu". UNHCR.org. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "They will be heard: The rape survivors of Minova". america.alJazeera.com. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ Reynolds, Emma (2 October 2015). "How military mass rape was buried". News.com.au. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ Mark Townsend, "Revealed: how the world turned its back on rape victims of Congo" Archived 16 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 13 June 2015; accessed 15 November 2017.

- ^ Vogel, Christoph; Radley, Ben (10 September 2014). "In Eastern Congo, economic colonialism in the guise of ethical consumption?". Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017 – via www.WashingtonPost.com.

- ^ "Eastern Congo: An Action Plan to End The World's Deadliest War - The Enough Project". EnoughProject.org. 16 July 2009. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "Conflict mineral law does more harm than good for Congo, say experts - Humanosphere". Humanosphere.org. 10 September 2014. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "allAfrica.com: Congo-Kinshasa: Striking Gold - How M23 and Its Allies Are Infiltrating Congo's Gold Trade". allAfrica.com. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Alfaro, Stephanie; et al. (2012). "Estimating human rights violations in South Kivu Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo: A population-based survey". Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 7 (3): 201–210. doi:10.1080/17450128.2012.690574. S2CID 71424371.

- Cox, T. Paul (2011). "Farming the battlefield: the meanings of war, cattle and soil in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo". Disasters. 36 (2): 233–248. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.2011.01257.x. PMID 21995623.

External links

[edit]- Renewed Crisis in North Kivu (HRW)

- Friends of the Congo History, reports, press releases, and current conditions in Congo conflict regions.

- UN Security Council Report United Nations press release, 26 November 2008