Kural

A typical published original Tamil version of the work | |

| Author | Valluvar |

|---|---|

| Original title | திருக்குறள் |

| Working title | Kural |

| Translator | See list of translations |

| Language | Old Tamil |

| Series | Eighteen Lesser Texts |

| Subject | |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Set in | Probably Post-Sangam era (c. 500 CE or earlier) |

Publication date | 1812 (first known printed edition, older palm-leaf manuscripts exist)[3] |

| Publication place | India |

Published in English | 1794 |

Original text | திருக்குறள் at Tamil Wikisource |

| Translation | Tirukkuṟaḷ at Wikisource |

The Tirukkuṟaḷ (Tamil: திருக்குறள், lit. 'sacred verses'), or shortly the Kural (Tamil: குறள்), is a classic Tamil language text consisting of 1,330 short couplets, or kurals, of seven words each.[4] The text is divided into three books with aphoristic teachings on virtue (aram), wealth (porul) and love (inbam), respectively.[1][5][6] It is widely acknowledged for its universality and secular nature.[7][8] Its authorship is traditionally attributed to Valluvar, also known in full as Thiruvalluvar. The text has been dated variously from 300 BCE to 5th century CE. The traditional accounts describe it as the last work of the third Sangam, but linguistic analysis suggests a later date of 450 to 500 CE and that it was composed after the Sangam period.[9]

The Kural text is among the earliest systems of Indian epistemology and metaphysics. The work is traditionally praised with epithets and alternative titles, including "the Tamil Veda" and "the Divine Book."[10][11] Written on the ideas of ahimsa,[12][13][14][15][16] it emphasizes non-violence and moral vegetarianism as virtues for an individual.[17][18][19][20][21][a] In addition, it highlights virtues such as truthfulness, self-restraint, gratitude, hospitality, kindness, goodness of spouse, duty, giving, and so forth,[22] besides covering a wide range of social and political topics such as king, ministers, taxes, justice, forts, war, greatness of army and soldier's honor, death sentence for the wicked, agriculture, education, and abstinence from alcohol and intoxicants.[23][24][25] It also includes chapters on friendship, love, sexual unions, and domestic life.[22][26] The text effectively denounced previously held misbeliefs that were common during the Sangam era and permanently redefined the cultural values of the Tamil land.[27]

The Kural has influenced scholars and leaders across the ethical, social, political, economic, religious, philosophical, and spiritual spheres over its history.[28] These include Ilango Adigal, Kambar, Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, Albert Schweitzer, Ramalinga Swamigal, V. O. Chidambaram Pillai, Karl Graul, George Uglow Pope, Alexander Piatigorsky, and Yu Hsi. The work remains the most translated, the most cited, and the most citable of Tamil literary works.[29] The text has been translated into at least 57 Indian and non-Indian languages, making it one of the most translated ancient works. Ever since it came to print for the first time in 1812, the Kural text has never been out of print.[30] The Kural is considered a masterpiece and one of the most important texts of the Tamil literature.[31] Its author is venerated for his selection of virtues found in the known literature and presenting them in a manner that is considered common and acceptable to all.[32] The Tamil people and the government of Tamil Nadu have long celebrated and upheld the text with reverence.[19]

Etymology and nomenclature

[edit]The term Tirukkuṟaḷ is a compound word made of two individual terms, tiru and kuṟaḷ. Tiru is an honorific Tamil term that corresponds to the Sanskrit term sri meaning "holy, sacred, excellent, honorable, and beautiful."[33] The term tiru has as many as 19 different meanings in Tamil.[34] Kuṟaḷ means something that is "short, concise, and abridged."[1] Etymologically, kuṟaḷ is the shortened form of kuṟaḷ pāttu, which is derived from kuruvenpāttu, one of the two Tamil poetic forms explained by the Tolkappiyam, the other one being neduvenpāttu.[35] According to Miron Winslow, kuṟaḷ is used as a literary term to indicate "a metrical line of 2 feet, or a distich or couplet of short lines, the first of 4 and the second of 3 feet."[36] Thus, Tirukkuṟaḷ literally comes to mean "sacred couplets."[1]

The work is highly cherished in the Tamil culture, as reflected by its twelve traditional titles: Tirukkuṟaḷ (the sacred kural), Uttaravedam (the ultimate Veda), Tiruvalluvar (eponymous with the author), Poyyamoli (the falseless word), Vayurai valttu (truthful praise), Teyvanul (the divine book), Potumarai (the common Veda), Valluva Maalai (garland made by the author), Tamil Manunool (Tamil ethical treatise), Tiruvalluva Payan (fruit of the author), Muppal (the three-fold path), and Tamilmarai (the Tamil Veda).[10][37] The work is traditionally grouped under the Eighteen Lesser Texts series of the late Sangam works, known in Tamil as Patiṉeṇkīḻkaṇakku.[35]

Date

[edit]The Kural has been dated variously from 300 BCE to 5th century CE. According to traditional accounts, it was the last work of the third Sangam and was subjected to a divine test, which it passed. The scholars who believe this tradition, such as Somasundara Bharathiar and M. Rajamanickam, date the text to as early as 300 BCE. Historian K. K. Pillay assigned it to the early 1st century CE.[9] According to Kamil Zvelebil, a Czech scholar of Tamil literature, these early dates such as 300 BCE to 1 BCE are unacceptable and not supported by evidence within the text. The diction and grammar of the Kural, and Valluvar's indebtedness to some earlier Sanskrit sources, suggest that he lived after the "early Tamil bardic poets," but before Tamil bhakti poets era.[10][38]

In 1959, S. Vaiyapuri Pillai assigned the work to around or after the 6th century CE. His proposal is based on the evidence that the Kural text contains a large proportion of Sanskrit loan words, shows awareness and indebtedness to some Sanskrit texts best dated to the first half of the 1st millennium CE, and the grammatical innovations in the language of the Kural literature.[38][b] Pillai published a list of 137 Sanskrit loan words in the Kural text.[39] Later scholars such as Thomas Burrow and Murray Barnson Emeneau show that 35 of these are of Dravidian origin and not Sanskrit loan words. Zvelebil states that an additional few have uncertain etymology and that future studies may prove those to be Dravidian.[39] The 102 remaining loan words from Sanskrit are "not negligible", and some of the teachings in the Kural text, according to Zvelebil, are "undoubtedly" based on the then extant Sanskrit works such as the Arthashastra and Manusmriti (also called the Manavadharmasastra).[39]

In his treatise of Tamil literary history published in 1974, Zvelebil states that the Kural text does not belong to the Sangam period and dates it to somewhere between 450 and 500 CE.[9] His estimate is based on the language of the text, its allusions to the earlier works, and its borrowing from some Sanskrit treatises.[10] Zvelebil notes that the text features several grammatical innovations that are absent in the older Sangam literature. The text also features a higher number of Sanskrit loan words compared with these older texts.[40] According to Zvelebil, besides being part of the ancient Tamil literary tradition, the author was also a part of the "one great Indian ethical, didactic tradition" as a few of the verses in the Kural text are "undoubtedly" translations of the verses of earlier Indian texts.[41]

In the 19th century and the early 20th century, European writers and missionaries variously dated the text and its author to between 400 and 1000 CE.[42] According to Blackburn, the "current scholarly consensus" dates the text and the author to approximately 500 CE.[42]

In 1921, in the face of incessant debate on the precise date, the Tamil Nadu government officially declared 31 BCE as the year of Valluvar at a conference presided over by Maraimalai Adigal.[9][43][44][45] On 18 January 1935, the Valluvar Year was added to the calendar.[46][c]

Author

[edit]"The book without a name by an author without a name."

—E. S. Ariel, 1848[47]

The Kural text was authored by Thiruvalluvar (lit. Saint Valluvar).[5] He is known by various other names including Poyyil Pulavar, Mudharpavalar, Deivappulavar, Nayanar, Devar, Nanmukanar, Mathanubangi, Sennabbodhakar, and Perunavalar.[48][49] There is negligible authentic information available about Valluvar's life.[50] For all practical purposes, neither his actual name nor the original title of his work can be determined with certainty.[51] The Kural text itself does not name its author.[52] The name Thiruvalluvar was first mentioned in the later era Shaivite Hindu text known as the Tiruvalluva Maalai, also of unclear date.[5] However, the Tiruvalluva Maalai does not mention anything about Valluvar's birth, family, caste or background. No other authentic pre-colonial texts have been found to support any legends about the life of Valluvar. Starting around early 19th century, numerous inconsistent legends on Valluvar in various Indian languages and English were published.[53]

Various claims have been made regarding Valluvar's family background and occupation in the colonial era literature, all inferred from selective sections of his text or hagiographies published since the colonial era started in Tamil Nadu.[54] One traditional version claims that he was a Paraiyar weaver.[55] Another theory is that he must have been from the agricultural caste of Vellalars because he extols agriculture in his work.[10] Another states he was an outcaste, born to a Pariah woman and a Brahmin father.[10][54] Mu Raghava Iyengar speculated that "valluva" in his name is a variation of "vallabha", the designation of a royal officer.[10] S. Vaiyapuri Pillai derived his name from "valluvan" (a Paraiyar caste of royal drummers) and theorized that he was "the chief of the proclaiming boys analogous to a trumpet-major of an army".[10][56] The traditional biographies not only are inconsistent, but also contain incredulous claims about the author of the Kural text. Along with various versions of his birth circumstances, many state he went to a mountain and met the legendary Agastya and other sages.[57] There are also accounts claiming that, during his return journey, Valluvar sat under a tree whose shadow sat still over him and did not move the entire day, he killed a demon, and many more.[57] Scholars consider these and all associated aspects of these hagiographic stories to be fiction and ahistorical, a feature common to "international and Indian folklore". The alleged low birth, high birth and being a pariah in the traditional accounts are also doubtful.[58] Traditionally, Valluvar is believed to have married to Vasuki[59] and had a friend and a disciple named Elelasingan.[60][61]

In a manner similar to speculations of the author's biography, there has been much speculation about his religion with no historical evidence. In determining Valluvar's religion, the crucial test to be applied according to M. S. Purnalingam Pillai is to analyze what religious philosophy he has not condemned,[62] adding that Valluvar has "not said a word against" the Saiva Siddhanta principles.[62] The Kural text is aphoristic and non-denominational in nature and can be selectively interpreted in many ways. This has led almost every major religious group in India, including Christianity during the Colonial era, to claim the work and its author as one of their own.[10] The 19th-century Christian missionary George Uglow Pope, for example, claimed that Valluvar must have lived in the 9th century CE, come in contact with Christian teachers such as Pantaenus of Alexandria, imbibed Christian ideas and peculiarities of Alexandrian teachers and then wrote the "wonderful Kurral" with an "echo of the 'Sermon of the Mount'."[51] This theory, however, is ahistorical and discredited.[63] According to Zvelebil, the ethics and ideas in Valluvar's work are not Christian ethics.[19][d] Albert Schweitzer hints that "the dating of the Kural has suffered, along with so many other literary and historical dates, philosophies and mythologies of India, a severe mauling at the hands of the Christian Missionaries, anxious to post-date all irrefutable examples of religious maturity to the Christian era."[64]

Valluvar is thought to have belonged to either Jainism or Hinduism.[19][26][65][66][67][68] This can be observed in his treatment of the concept of ahimsa or non-violence, which is the principal concept of both the religions.[a] In the 1819 translation, Francis Whyte Ellis mentions that the Tamil community debates whether Valluvar was a Jain or Hindu.[69] According to Zvelebil, Valluvar's treatment of the chapters on moral vegetarianism and non-killing reflects the Jain precepts.[19][a] Certain epithets for God and ascetic values found in the text are found in Jainism, states Zvelebil. He theorizes that Valluvar was probably "a learned Jain with eclectic leanings", who was well acquainted with the earlier Tamil literature and also had knowledge of the Sanskrit texts.[50] According to A. Chakravarthy Nainar, the Jaina tradition associates the work with Kunda Kunda Acharya, also known as Elachariyar in the Tamil region, the chief of the Southern Pataliputra Dravidian Sanghaat, who lived around the latter half of the first century BCE and the former half of the first century CE.[70] Nevertheless, early Digambara or Śvetāmbara Jaina texts do not mention Valluvar or the Kural text. The first claim of Valluvar as an authority appears in a 16th-century Jain text.[71]

"It's the author's innate nature to select the best virtues

found in all the known literature and present them

in a manner that is acceptable to all."

—Parimelalhagar about Valluvar, 13th century CE[72]

Valluvar's writings, according to scholars, also suggest that he might have belonged to Hinduism. Hindu teachers have mapped his teachings in the Kural literature to the teachings found in Hindu texts.[66][67] The three parts that the Kural is divided into, namely, aṟam (virtue), poruḷ (wealth) and inbam (love), aiming at attaining veedu (ultimate salvation), follow, respectively, the four foundations of Hinduism, namely, dharma, artha, kama and moksha.[1][68] While the text extols the virtue of non-violence, it also dedicates many of 700 poruḷ couplets to various aspects of statecraft and warfare in a manner similar to the Hindu text Arthasastra.[65] For example, according to the text, an army has a duty to kill in battle, and a king must execute criminals for justice.[73][e] Valluvar's mentioning of God Vishnu in couplets 610 and 1103 and Goddess Lakshmi in couplets 167, 408, 519, 565, 568, 616, and 617 suggests the Vaishnavite beliefs of the author.[74][75] P. R. Natarajan lists at least 24 different usage of Hindu origin in 29 different couplets across the Kural text.[75] According to Purnalingam Pillai, who is known for his critique of Brahminism, a rational analysis of the Kural text suggests that Valluvar was a Hindu, and not a Jain.[76] Matthieu Ricard believes Valluvar belonged to the Shaivite tradition of South India.[77] According to Thomas Manninezhath – a theology scholar who grew up in South India, the Tirukkuṟaḷ is believed by the natives to reflect Advaita Vedanta philosophy and teaches an "Advaitic way of life".[78]

Notwithstanding these debates, Valluvar is praised by scholars for his innate nature to select the virtues found in all the known works and present them in a manner that is considered common and acceptable to everyone.[32] The author is remembered and cherished for his universal secular values,[79] and his treatise has been called Ulaga Podhu Marai (the universal scripture).[80][81][82][83]

Contents

[edit]The Kural is structured into 133 chapters, each containing 10 couplets (or kurals), for a total of 1,330 couplets.[84][f] All the couplets are in kural venba metre, and all the 133 chapters have an ethical theme and are grouped into three parts, or "books":[84][85]

Tirukkuṟaḷ

- Book I – Aṟam (அறம்): Book of Virtue (Dharma), dealing with moral values of an individual[84] and essentials of yoga philosophy[85] (Chapters 1–38)

- Book II – Poruḷ (பொருள்): Book of Polity (Artha), dealing with socio-economic values,[84] polity, society and administration[85] (Chapters 39–108)

- Book III – Inbam (இன்பம்): Book of Love (Kama), dealing with psychological values[84] and love[85] (Chapters 109–133)

"Virtue will confer heaven and wealth; what greater source of happiness can man possess?"

The book on aṟam (virtue) contains 380 verses, that of poruḷ (wealth) has 700 and that of inbam or kāmam (love) has 250. Each kural or couplet contains exactly seven words, known as cirs, with four cirs on the first line and three on the second, following the kural metre. A cir is a single or a combination of more than one Tamil word. For example, the term Tirukkuṟaḷ is a cir formed by combining the two words tiru and kuṟaḷ.[84] The Kural text has a total of 9310 cirs made of 12,000 Tamil words, of which about 50 words are from Sanskrit and the remaining are Tamil original words.[87] A manual count has shown that there are in total 42,194 letters in the entire work, with the shortest ones (kurals 833 and 1304) containing 23 letters and the longest ones (kurals 957 and 1246) containing 39 letters each.[88] Among the 133 chapters, the fifth chapter is the longest with 339 letters and the 124th chapter is the shortest with 280 letters.[89]

Of the 1,330 couplets in the text, 40 couplets relate to god, rain, ascetics, and virtue; 340 on fundamental everyday virtues of an individual; 250 on royalty; 100 on ministers of state; 220 on essential requirements of administration; 130 on social morality, both positive and negative; and 250 on human love and passion.[26][90]

Along with the Bhagavad Gita, the Kural is one of the earliest systems of Indian epistemology and metaphysics.[91] The work largely reflects the first three of the four ancient Indian aims in life, known as purushaarthas, viz., virtue (dharma), wealth (artha) and love (kama).[1][8][68][92][93][94] The fourth aim, namely, salvation (moksha) has been omitted from being dealt with as the fourth book since it does not lend itself to didactic treatment,[95] but is implicit in the last five chapters of Book I.[96][g] The components of aṟam, poruḷ and inbam encompasses both the agam and puram genres of the Tamil literary tradition as explained in the Tolkappiyam.[97] According to Sharma, dharma (aṟam) refers to ethical values for the holistic pursuit of life, artha (poruḷ) refers to wealth obtained in ethical manner guided by dharma, and kāma (Inbam) refers to pleasure and fulfilment of one's desires, also guided by dharma.[98] The corresponding goals of poruḷ and inbam are desirable, yet both need to be regulated by aṟam, according to J. Arunadevi.[99] On the same lines, Amaladass concludes that the Kural expresses that dharma and artha should not be separated from one another.[100] According to Indian philosophical tradition, one must remain unattached to wealth and possessions, which can either be transcended or sought with detachment and awareness, and pleasure needs to be fulfilled consciously and without harming anyone.[98] The Indian tradition also holds that there exists an inherent tension between artha and kama.[98] Thus, wealth and pleasure must be pursued with an "action with renunciation" (Nishkama Karma), that is, one must act without craving in order to resolve this tension.[98][101][h]

The content of Tirukkuṟaḷ, according to Zvelebil:[22]

- Book I—Book of Virtue (38 chapters)

- Chapter 1. In Praise of God (கடவுள் வாழ்த்து kaṭavuḷ vāḻttu): Couplets 1–10

- Chapter 2. The Excellence of Rain (வான் சிறப்பு vāṉ ciṟappu): 11–20

- Chapter 3. The Greatness of Those Who Have Renounced (நீத்தார் பெருமை nīttār perumai): 21–30

- Chapter 4. Assertion of the strength of Virtue (அறன் வலியுறுத்தல் aṟaṉ valiyuṟuttal): 31–40

- Chapter 5. Domestic Life (இல்வாழ்க்கை ilvāḻkkai): 41–50

- Chapter 6. The Goodness of Spouse (வாழ்க்கைத்துணை நலம் vāḻkkaittuṇai nalam): 51–60

- Chapter 7. The Obtaining of Sons (புதல்வரைப் பெறுதல் putalvaraip peṟutal): 61–70

- Chapter 8. The Possession of Affection (அன்புடைமை aṉpuṭaimai): 71–80

- Chapter 9. Hospitality (விருந்தோம்பல் viruntōmpal): 81–90

- Chapter 10. Kindly Speech (இனியவை கூறல் iṉiyavai kūṟal): 91–100

- Chapter 11. Gratitude (செய்ந்நன்றி அறிதல் ceynnaṉṟi aṟital): 101–110

- Chapter 12. Impartiality (நடுவு நிலைமை naṭuvu nilaimai): 111–120

- Chapter 13. Self-control (அடக்கமுடைமை aṭakkamuṭaimai): 121–130

- Chapter 14. Decorous Conduct (ஒழுக்கமுடைமை oḻukkamuṭaimai): 131–140

- Chapter 15. Not Coveting Another's Wife (பிறனில் விழையாமை piṟaṉil viḻaiyāmai): 141–150

- Chapter 16. Forbearance (பொறையுடைமை poṟaiyuṭaimai): 151–160

- Chapter 17. Absence of Envy (அழுக்காறாமை aḻukkāṟāmai): 161–170

- Chapter 18. Not Coveting (வெஃகாமை veḵkāmai): 171–180

- Chapter 19. Not Speaking Evil of the Absent (புறங்கூறாமை puṟaṅkūṟāmai): 181–190

- Chapter 20. Not Speaking Senseless Words (பயனில சொல்லாமை payaṉila collāmai): 191–200

- Chapter 21. Dread of Evil Deeds (தீவினையச்சம் tīviṉaiyaccam): 201–210

- Chapter 22. Recognition of Duty (ஒப்புரவறிதல் oppuravaṟital): 211–220

- Chapter 23. Giving (ஈகை īkai): 221–230

- Chapter 24. Fame (புகழ் pukaḻ): 231–240

- Chapter 25. Possession of Benevolence (அருளுடைமை aruḷuṭaimai): 241–250

- Chapter 26. Abstinence from Flesh (Vegetarianism) (புலான் மறுத்தல் pulāṉmaṟuttal): 251–260

- Chapter 27. Penance (தவம் tavam): 261–270

- Chapter 28. Inconsistent Conduct (கூடாவொழுக்கம் kūṭāvoḻukkam): 271–280

- Chapter 29. Absence of Fraud (கள்ளாமை kaḷḷāmai): 281–290

- Chapter 30. Truthfulness (வாய்மை vāymai): 291–300

- Chapter 31. Refraining from Anger (வெகுளாமை vekuḷāmai): 301–310

- Chapter 32. Inflicting No Pain (இன்னா செய்யாமை iṉṉāceyyāmai): 311–320

- Chapter 33. Not Killing (கொல்லாமை kollāmai): 321–330

- Chapter 34. Instability of Earthly Things (நிலையாமை nilaiyāmai): 331–340

- Chapter 35. Renunciation (துறவு tuṟavu): 341–350

- Chapter 36. Perception of the Truth (மெய்யுணர்தல் meyyuṇartal): 351–360

- Chapter 37. Rooting Out Desire (அவாவறுத்தல் avāvaṟuttal): 361–370

- Chapter 38. Past Deeds (ஊழ் ūḻ = karma): 371–380

- Book II—Book of Polity (70 chapters)

- Chapter 39. The Greatness of a King (இறைமாட்சி iṟaimāṭci): 381–390

- Chapter 40. Learning (கல்வி kalvi): 391–400

- Chapter 41. Ignorance (கல்லாமை kallāmai): 401–410

- Chapter 42. Learning through Listening (கேள்வி kēḷvi): 411–420

- Chapter 43. Possession of Knowledge (அறிவுடைமை aṟivuṭaimai): 421–430

- Chapter 44. The Correction of Faults (குற்றங்கடிதல் kuṟṟaṅkaṭital): 431–440

- Chapter 45. Seeking the Help of the Great (பெரியாரைத் துணைக்கோடல் periyārait tuṇaikkōṭal): 441–450

- Chapter 46. Avoiding Mean Associations (சிற்றினஞ்சேராமை ciṟṟiṉañcērāmai): 451–460

- Chapter 47. Acting after Right Consideration (தெரிந்து செயல்வகை terintuceyalvakai): 461–470

- Chapter 48. Recognition of Power (வலியறிதல் valiyaṟital): 471–480

- Chapter 49. Recognition of Opportunity (காலமறிதல் kālamaṟital): 481–490

- Chapter 50. Recognition of Place (இடனறிதல் iṭaṉaṟital): 491–500

- Chapter 51. Selection and Confidence (தெரிந்து தெளிதல் terintuteḷital): 501–510

- Chapter 52. Selection and Employment (தெரிந்து வினையாடல் terintuviṉaiyāṭal): 511–520

- Chapter 53. Cherishing One's Kin (சுற்றந்தழால் cuṟṟantaḻāl): 521–530

- Chapter 54. Unforgetfulness (பொச்சாவாமை poccāvāmai): 531–540

- Chapter 55. The Right Sceptre (செங்கோன்மை ceṅkōṉmai): 541–550

- Chapter 56. The Cruel Sceptre (கொடுங்கோன்மை koṭuṅkōṉmai): 551–560

- Chapter 57. Absence of Tyranny (வெருவந்த செய்யாமை veruvantaceyyāmai): 561–570

- Chapter 58. Benignity (கண்ணோட்டம் kaṇṇōṭṭam): 571–580

- Chapter 59. Spies (ஒற்றாடல் oṟṟāṭal): 581–590

- Chapter 60. Energy (ஊக்கமுடைமை ūkkamuṭaimai): 591–600

- Chapter 61. Unsluggishness (மடியின்மை maṭiyiṉmai): 601–610

- Chapter 62. Manly Effort (ஆள்வினையுடைமை āḷviṉaiyuṭaimai): 611–620

- Chapter 63. Not Despairing in Trouble (இடுக்கண் அழியாமை iṭukkaṇ aḻiyāmai): 621–630

- Chapter 64. Ministry (அமைச்சு amaiccu): 631–640

- Chapter 65. Power in Speech (சொல்வன்மை colvaṉmai): 641–650

- Chapter 66. Purity in Action (வினைத்தூய்மை viṉaittūymai): 651–660

- Chapter 67. Firmness in Deeds (வினைத்திட்பம் viṉaittiṭpam): 661–670

- Chapter 68. Method of Action (வினை செயல்வகை viṉaiceyalvakai): 671–680

- Chapter 69. The Envoy (தூது tūtu): 681–690

- Chapter 70. Conduct in the Presence of King (மன்னரைச் சேர்ந்தொழுதல் maṉṉaraic cērntoḻutal): 691–700

- Chapter 71. Knowledge of Signs (குறிப்பறிதல் kuṟippaṟital): 701–710

- Chapter 72. Knowledge in the Council Chamber (அவையறிதல் avaiyaṟital): 711–720

- Chapter 73. Not to Fear the Council (அவையஞ்சாமை avaiyañcāmai): 721–730

- Chapter 74. The Land (நாடு nāṭu): 731–740

- Chapter 75. The Fort (அரண் araṇ): 741–750

- Chapter 76. Ways of Accumulating Wealth (பொருள் செயல்வகை poruḷceyalvakai): 751–760

- Chapter 77. Greatness of the Army (படைமாட்சி paṭaimāṭci): 761–770

- Chapter 78. Military Spirit (படைச்செருக்கு paṭaiccerukku): 771–780

- Chapter 79. Friendship (நட்பு naṭpu): 781–790

- Chapter 80. Scrutiny of Friendships (நட்பாராய்தல் naṭpārāytal): 791–800

- Chapter 81. Familiarity (பழைமை paḻaimai): 801–810

- Chapter 82. Evil Friendship (தீ நட்பு tī naṭpu): 811–820

- Chapter 83. Faithless Friendship (கூடா நட்பு kūṭānaṭpu): 821–830

- Chapter 84. Folly (பேதைமை pētaimai): 831–840

- Chapter 85. Ignorance (புல்லறிவாண்மை pullaṟivāṇmai): 841–850

- Chapter 86. Hostility (இகல் ikal): 851–860

- Chapter 87. The Excellence of Hate (பகை மாட்சி pakaimāṭci): 861–870

- Chapter 88. Skill in the Conduct of Quarrels (பகைத்திறந்தெரிதல் pakaittiṟanterital): 871–880

- Chapter 89. Secret Enmity (உட்பகை uṭpakai): 881–890

- Chapter 90. Not Offending the Great (பெரியாரைப் பிழையாமை periyāraip piḻaiyāmai): 891–900

- Chapter 91. Being Led by Women (பெண்வழிச் சேறல் peṇvaḻiccēṟal): 901–910

- Chapter 92. Wanton Women (வரைவின் மகளிர் varaiviṉmakaḷir): 911–920

- Chapter 93. Abstinence from Liquor (கள்ளுண்ணாமை kaḷḷuṇṇāmai): 921–930

- Chapter 94. Gambling (சூது cūtu): 931–940

- Chapter 95. Medicine (மருந்து maruntu): 941–950

- Chapter 96. Nobility (குடிமை kuṭimai): 951–960

- Chapter 97. Honour (மானம் māṉam): 961–970

- Chapter 98. Greatness (பெருமைperumai): 971–980

- Chapter 99. Perfect Excellence (சான்றாண்மை cāṉṟāṇmai): 981–990

- Chapter 100. Courtesy (பண்புடைமை paṇpuṭaimai): 991–1000

- Chapter 101. Useless Wealth (நன்றியில் செல்வம் naṉṟiyilcelvam): 1001–1010

- Chapter 102. Shame (நாணுடைமை nāṇuṭaimai): 1011–1020

- Chapter 103. On Raising the Family (குடிசெயல்வகை kuṭiceyalvakai): 1021–1030

- Chapter 104. Agriculture (உழவு uḻavu): 1031–1040

- Chapter 105. Poverty (நல்குரவு nalkuravu): 1041–1050

- Chapter 106. Mendicancy (இரவுiravu): 1051–1060

- Chapter 107. The Dread of Mendicancy (இரவச்சம் iravaccam): 1061–1070

- Chapter 108. Vileness (கயமை kayamai): 1071–1080

- Book III—Book of Love (25 chapters)

- Chapter 109. Mental Disturbance Caused by the Lady's Beauty (தகையணங்குறுத்தல் takaiyaṇaṅkuṟuttal): 1081–1090

- Chapter 110. Recognizing the Signs (குறிப்பறிதல்kuṟippaṟital): 1091–1100

- Chapter 111. Rejoicing in the Sexual Union (புணர்ச்சி மகிழ்தல் puṇarccimakiḻtal): 1101–1110

- Chapter 112. Praising Her Beauty (நலம் புனைந்துரைத்தல் nalampuṉainturaittal): 1111–1120

- Chapter 113. Declaration of Love's Excellence (காதற் சிறப்புரைத்தல் kātaṟciṟappuraittal): 1121–1130

- Chapter 114. The Abandonment of Reserve (நாணுத் துறவுரைத்தல் nāṇuttuṟavuraittal): 1131–1140

- Chapter 115. Rumour (அலரறிவுறுத்தல் alaraṟivuṟuttal): 1141–1150

- Chapter 116. Separation is Unendurable (பிரிவாற்றாமை pirivāṟṟāmai): 1151–1160

- Chapter 117. Complaining of Absence (படர் மெலிந்திரங்கல்paṭarmelintiraṅkal): 1161–1170

- Chapter 118. Eyes Concerned with Grief (கண்விதுப்பழிதல் kaṇvituppaḻital): 1171–1180

- Chapter 119. Grief's Pallor (பசப்பறு பருவரல் pacappaṟuparuvaral): 1181–1190

- Chapter 120. The Solitary Anguish (தனிப்படர் மிகுதி taṉippaṭarmikuti): 1191–1200

- Chapter 121. Sad Memories (நினைந்தவர் புலம்பல் niṉaintavarpulampal): 1201–1210

- Chapter 122. Visions of Night (கனவுநிலையுரைத்தல் kaṉavunilaiyuraittal): 1211–1220

- Chapter 123. Lamentations at Evening (பொழுதுகண்டிரங்கல் poḻutukaṇṭiraṅkal): 1221–1230

- Chapter 124. Wasting Away (உறுப்பு நலனழிதல் uṟuppunalaṉaḻital): 1231–1240

- Chapter 125. Soliloquies (நெஞ்சொடு கிளத்தல் neñcoṭukiḷattal): 1241–1250

- Chapter 126. Reserve Destroyed (நிறையழிதல் niṟaiyaḻital): 1251–1260

- Chapter 127. Longing for the Return (அவர்வயின் விதும்பல் avarvayiṉvitumpal): 1261–1270

- Chapter 128. Reading of the Signs (குறிப்பறிவுறுத்தல் kuṟippaṟivuṟuttal): 1271–1280

- Chapter 129. Desire for Reunion (புணர்ச்சி விதும்பல் puṇarccivitumpal): 1281–1290

- Chapter 130. Arguing with One's Heart (நெஞ்சொடு புலத்தல் neñcoṭupulattal): 1291–1300

- Chapter 131. Lover's Quarrel (புலவி pulavi): 1301–1310

- Chapter 132. Petty Jealousies (புலவி நுணுக்கம் pulavi nuṇukkam): 1311–1320

- Chapter 133. Pleasures of Temporary Variance (ஊடலுவகை ūṭaluvakai): 1321–1330

Structure

[edit]The Kural text is the work of a single author because it has a consistent "language, formal structure and content-structure", states Zvelebil.[102] Neither is the Kural an anthology nor is there any later additions to the text.[102] The division into three parts (muppāl) is probably the author's work. However, the subdivisions beyond these three, known as iyals, as found in some surviving manuscripts and commentaries, are likely later additions because there are variations between these subtitles found in manuscripts and those in historical commentaries.[103][104]

Starting from the medieval era, commentators have multifariously divided the Kural text into different iyal sub-divisions, grouping the Kural chapters diversely under them.[105] The idea of subdividing the Tirukkural into iyal sub-divisions was first put forth by a Tiruvalluva Maalai verse attributed to Nanpalur Sirumedhaviyar.[106][107] The medieval commentators have variously grouped the chapters of Book I into three and four iyals, grouping the original chapters diversely under these divisions and thus changing the order of the chapters widely;[104][108][109] while Parimelalhagar divided it into three iyals, others divided it into four,[110] with some 20th-century commentators going up to six.[108] Book II has been variously subdivided between three and six iyals.[108][111][112] The chapters of Book III have been variously grouped between two and five iyals.[108][110][113] For example, the following subdivisions or iyals are found in Parimelalhagar's version, which greatly varies from that of Manakkudavar:[114]

- Chapters 1–4: Introduction

- Chapters 5–24: Domestic virtue

- Chapters 25–38: Ascetic virtue

- Chapters 39–63: Royalty, the qualities of the leader of men

- Chapters 64–73: The subject and the ruler

- Chapters 74–96: Essential parts of state, shrewdness in public life

- Chapters 97–108: Reaching perfection in social life

- Chapters 109–115: Concealed love

- Chapters 116–133: Wedded love

Modern scholars and publishers chiefly follow Parimelalhagar's model for couplet numbering, chapter ordering, and grouping the chapters into iyals.[115]

Such subdivisions are likely later additions, but the couplets themselves have been preserved in the original form and there is no evidence of later revisions or insertions into the couplets.[102][114] Thus, in spite of these later subdivisions by the medieval commentators, both the domestic and ascetic virtues in Book I are addressed to the householder or commoner.[116] As Yu Hsi puts it, "Valluvar speaks to the duties of the commoner acting in different capacities as son, father, husband, friend, citizen, and so forth."[117] According to A. Gopalakrishnan, ascetic virtues in the Kural does not mean renunciation of household life or pursuing of the conventional ascetic life, but only refers to giving up immoderate desires and having self-control that is expected of every individual.[116] According to Joanne Punzo Waghorne, professor of religion and South Asian studies at the Syracuse University, the Kural is "a homily on righteous living for the householder."[59]

Like the three-part division, and unlike the iyal subdivisions, the grouping of the couplets into chapters is the author's.[118] Every topic that Valluvar handles in his work are presented in ten couplets forming a chapter, and the chapter is usually named using a keyword found in the couplets in it.[118] Exceptions to this convention are found in all the three books of the Kural text as in Chapter 1 in the Book of Aram, Chapter 78 in the Book of Porul, and Chapter 117 in the Book of Inbam, where the words used in title of the chapters are not found anywhere in the chapter's couplets.[119] Here again, the titles of all the chapters of the Kural text are given by Valluvar himself.[119] According to S. N. Kandasamy, the naming of the first chapter of the Kural text is in accord with the conventions used in the Tolkappiyam.[120]

According to Zvelebil, the content of the Kural text is "undoubtedly patterned" and "very carefully structured."[121] There are no structural gaps in the text, with every couplet indispensable for the structured whole.[103] There are two distinct meanings for every couplet, namely, a structural one and a proverbial one.[103] In their isolated form, that is, when removed from the context of the 10-couplet chapter, the couplets lose their structural meaning but retain the "wise saying, moral maxim" sense.[103] In isolation, a couplet is "a perfect form, possessing, in varying degree, the prosodic and rhetoric qualities of gnomic poetry."[103] Within the chapter-structure, the couplets acquire their structural meaning and reveal the more complete teaching of the author.[103] This, Zvelebil states, is the higher pattern in the Kural text, and finally, in relation to the entire work, they acquire perfection in the totality of their structure.[103] In terms of structural flow, the text journeys the reader from "the imperfect, incomplete" state of man implicit in the early chapters to the "physically, morally, intellectually and emotionally perfect" state of man living as a husband and citizen, states Zvelebil.[122] In poetic terms, it fuses verse and aphoristic form in diction in a "pithy, vigorous, forceful and terse" manner. Zvelebil calls it an ethics text that expounds a universal, moral and practical approach to life. According to Mahadevan, Valluvar is more considerate about the substance than the linguistic appeal of his writing throughout the work.[123]

Substance

[edit]The Kural text is marked by pragmatic idealism,[8][124] focused on "man in the totality of his relationships".[125] Despite being a classic, the work has little scope for any poetic excellence.[126] According to Zvelebil, the text does not feature "true and great poetry" throughout the work, except, notably, in the third book, which deals with love and pleasure.[127] This emphasis on substance rather than poetry, according to scholars, suggests that Valluvar's main aim was not to produce a work of art, but rather an instructive text focused on wisdom, justice, and ethics.[127]

The Kural text begins with an invocation of God and then praises the rain for being the vitalizer of all life forms on earth.[128][129] It proceeds to describe the qualities of a righteous person, before concluding the introduction by emphasizing the value of aṟam or virtue.[128][130] It continues to treat aṟam in every action in life, supplementing it with a chapter on predestination.[95] Valluvar extols rain next only to God for it provides food and serves as the basis of a stable economic life by aiding in agriculture, which the author asserts as the most important economic activity later in Book II of the Kural text.[128][131]

"The greatest virtue of all is non-killing; truthfulness cometh only next."

The three books of the Kural base aṟam or dharma (virtue) as their cornerstone,[133][134] resulting in the work being collectively referred to simply as Aṟam.[118][135][136][137] Valluvar holds that aṟam is common for all, irrespective of whether the person is a bearer of palanquin or the rider in it.[138][139] According to Albert Schweitzer, the idea that good must be done for its own sake comes from various couplets across the Kural text.[140] In his 1999 work, Japanese Indologist Takanobu Takahashi noted that Valluvar dealt with virtues in terms of good rather than in terms of caste-based duties and when he discussed politics he addressed simply a man rather than a king.[141] The text is a comprehensive pragmatic work that presents philosophy in the first part, political science in the second and poetics in the third.[142][143] Of the three books of the Kural literature, the second one on politics and kingdom (poruḷ) is about twice the size of the first, and three times that of the third.[144] In the 700 couplets on poruḷ (53 percent of the text), Valluvar mostly discusses statecraft and warfare.[145] While other Sangam texts approved of, and even glorified,[146] the four immoral deeds of meat-eating, alcohol consumption, polygamy, and prostitution, the Kural literature strongly condemns these as crimes,[147][148] reportedly for the first time in the history of the Tamil land.[27][149][150] In addition to these, the Kural also strongly proscribes gambling.[151]

The Kural is based on the doctrine of ahimsa.[12][13][14][15][16] According to Schweitzer, the Kural "stands for the commandment not to kill and not to damage."[140] Accordingly, Valluvar dictates the householder to renounce the eating of meat "in order that he may become a man of grace."[152] While the Bible and other Abrahamic texts condemns only the taking away of human life, the Kural is cited for unequivocally and exclusively condemning the "literal taking away of life,"[63] regardless of whether it is human or animal.[63][153][154] The greatest of personal virtues according to the Kural text is non-killing, followed by veracity,[155][156][157] and the two greatest sins that Valluvar feels very strongly are ingratitude and meat-eating.[20][156][158][i] According to J. M. Nallaswamy Pillai, the Kural differs from every other work on morality in that it follows ethics, surprisingly a divine one, even in its Book of Love.[159] In the words of Gopalkrishna Gandhi, Valluvar maintains his views on personal morality even in the Book of Love, where one can normally expect greater poetic leniency, by describing the hero as "a one-woman man" without concubines.[160] In a social and political context, the Kural text glorifies valour and victory during war and recommends a death sentence for the wicked only as a means of justice.[18][161][162]

According to Kaushik Roy, the Kural text in substance is a classic on realism and pragmatism, and it is not a mystic, purely philosophical document.[145] Valluvar presents his theory of state using six elements: army (patai), subjects (kuti), treasure (kul), ministers (amaiccu), allies (natpu), and forts (aran).[145] Valluvar also recommends forts and other infrastructure, supplies and food storage in preparation for siege.[145][163] A king and his army must always be ready for war, and should launch a violent offensive, at the right place and right time, when the situation so demands and particularly against morally weak and corrupt kingdoms. A good and strong kingdom must be protected with forts made of thick, high and impenetrable walls. The text recommends a hierarchical military organization staffed with fearless soldiers who are willing to die in war,[164] drawing from the Hindu concepts of non-mystic realism and readiness for war.[165]

"The sceptre of the king is the firm support of the Vedas of the Brahmin, and of all virtues therein described."

(Kural 543; John Lazarus 1885[166] & A. K. Ananthanathan 1994[167]).

The Kural text does not recommend democracy; rather it accepts a royalty with ministers bound to a code of ethics and a system of justice.[168] The king in the text, states K. V. Nagarajan, is assigned the "role of producing, acquiring, conserving, and dispensing wealth".[145][168] The king's duty is to provide a just rule, be impartial and have courage in protecting his subjects and in meting out justice and punishment. The text supports death penalty for the wicked in the book of poruḷ, but does so only after emphasizing non-killing as every individual's personal virtue in the book of aṟam.[168] The Kural cautions against tyranny, appeasement and oppression, with the suggestion that such royal behavior causes natural disasters, depletes the state's wealth and ultimately results in the loss of power and prosperity.[169] In the sphere of business, a study employing hermeneutics concludes that the Kural advocates a consciousness and spirit-centered approach to the subject of business ethics on the basis of eternal values and moral principles that should govern the conduct of business leaders.[170]

Valluvar remained a generalist rather than a specialist in any particular field.[83] He never indulged in specifics but always stressed on the basic principles of morality.[83] This can be seen across the Kural text: while Valluvar talks about worshiping God, he refrains from mentioning the way of worshiping; he refers to God as an "ultimate reality" without calling him by any name; he talks about land, village, country, kingdom, and king but never refers them by any name; though he mentions about the value of reading and reciting scriptures, he never names them; he talks about the values of charity without laying down the rules for it; though he repeatedly emphasizes about the importance of learning, he never says what is to be learnt; he recommends taxation in governance but does not suggest any proportion of collection.[83]

Similes and pseudo-contradictions

[edit]

Scholars claim that Valluvar seldom shows any concern as to what similes and superlatives he used earlier while writing later chapters, purposely allowing for some repetitions and apparent contradictions in ideas one can find in the Kural text.[172] Despite knowing its seemingly contradictory nature from a purist point of view, the author is said to employ this method to emphasise the importance of the given code of ethic.[172][173] Following are some of the instances where Valluvar is quoted as employing pseudo-contradictions to expound the virtues.[90]

- While in Chapter 93 Valluvar writes on the evils of intoxication,[174] in Chapter 109 he uses the same to show the sweetness of love by saying love is sweeter than wine.[175]

- To the question "What is wealth of all wealth?" Valluvar points to two different things, namely, grace (kural 241) and hearing (kural 411).[172]

- In regard to the virtues one should follow dearly even at the expense of other virtues, Valluvar points to veracity (kural 297), not coveting another's wife (kural 150), and not being called a slanderer (kural 181). In essence, however, in Chapter 33 he crowns non-killing as the foremost of all virtues, pushing even the virtue of veracity to the second place (kural 323).[176]

- Whereas he says that one can eject what is natural or inborn in him (kural 376),[177][178] he indicates that one can overcome the inherent natural flaws by getting rid of laziness (kural 609).[179]

- While in Chapter 7 he asserts that the greatest gain men can obtain is by their learned children (kural 61),[180][181] in Chapter 13 he says that it is that which is obtained by self-control (kural 122).[182]

The ethical connections between these verses are widely elucidated ever since the medieval commentaries. For example, Parimelalhagar elucidates the ethical connections between couplets 380 and 620, 481 and 1028, 373 and 396, and 383 and 672 in his commentary.[183]

Commentaries and translations

[edit]Commentaries

[edit]

The Kural is one of the most reviewed of all works in Tamil literature, and almost every notable scholar of Tamil has written exegesis or commentaries (explanation in prose or verse), known in Tamil as urai, on it.[184][j] Some of the Tamil literature that was composed after the Kural quote or borrow its couplets in their own texts.[185] According to Aravindan, these texts may be considered as the earliest commentaries to the Kural text.[184]

Dedicated commentaries on the Kural text began to appear about and after the 10th century CE. There were at least ten medieval commentaries of which only six have survived into the modern era. The ten medieval commentators include Manakkudavar, Dharumar, Dhamatthar, Nacchar, Paridhiyar, Thirumalaiyar, Mallar, Pari Perumal, Kaalingar, and Parimelalhagar, all of whom lived between the 10th and the 13th centuries CE. Of these, only the works of Manakkudavar, Paridhi, Kaalingar, Pari Perumal, and Parimelalhagar are available today. The works of Dharumar, Dhaamatthar, and Nacchar are only partially available. The commentaries by Thirumalaiyar and Mallar are lost completely. The best known among these are the commentaries by Parimelalhagar, Kaalingar, and Manakkudavar.[26][184][186] Among the ten medieval commentaries, scholars have found spelling, homophonic, and other minor textual variations in a total of 900 couplets, including 217 couplets in Book I, 487 couplets in Book II, and 196 couplets in Book III.[187]

"Valluvar is a cunning technician, who, by prodigious self-restraint and artistic vigilance, super-charges his words with meaning and achieves an incredible terseness and an irreducible density. His commentators have, therefore, to squeeze every word and persuade it to yield its last drop of meaning."

— S. Maharajan, 1979.[188]

The best known and influential historic commentary on the Kural text is the Parimelalhakiyar virutti. It was written by Parimelalhagar – a Vaishnava Brahmin, likely based in Kanchipuram, who is the last of the ten medieval commentators and who lived about or before 1272 CE.[189] Along with the Kural text, this commentary has been widely published and is in itself a Tamil classic.[190] Parimelalhagar's commentary has survived over the centuries in many folk and scholarly versions. A more scholarly version of this commentary was published by Krisnamachariyar in 1965.[189] According to Norman Cutler, Parimelalhagar's commentary interprets and maneuvers the Kural text within his own context, grounded in the concepts and theological premises of Hinduism. His commentary closely follows the Kural's teachings, while reflecting both the cultural values and textual values of the 13th- and 14th-century Tamil Nadu. Valluvar's text can be interpreted and maneuvered in other ways, states Cutler.[190]

Besides the ten medieval commentaries, there are at least three more commentaries written by unknown medieval authors.[191] One of them was published under the title "Palhaiya Urai" (meaning ancient commentary), while the second one was based on Paridhiyar's commentary.[191] The third one was published in 1991 under the title "Jaina Urai" (meaning Jaina commentary) by Saraswathi Mahal Library in Thanjavur.[192] Following these medieval commentaries, there are at least 21 venpa commentaries to the Kural, including Somesar Mudumoli Venba, Murugesar Muduneri Venba, Sivasiva Venba, Irangesa Venba, Vadamalai Venba, Dhinakara Venba, and Jinendra Venba, all of which are considered commentaries in verse form.[193][194][195] The 16th-century commentary by Thirumeni Rathna Kavirayar,[196] and the 19th-century commentaries by Ramanuja Kavirayar[196] and Thanigai Saravanaperumalaiyar[197] are some of the well-known scholarly commentaries on the Kural text before the 20th century.

Several modern commentaries started appearing in the 19th and 20th centuries. Of these, the commentaries by Kaviraja Pandithar and U. V. Swaminatha Iyer are considered classic by modern scholars.[3] Some of the commentaries of the 20th century include those by K. Vadivelu Chettiar,[198] Krishnampet K. Kuppusamy Mudaliar,[199] Iyothee Thass, V. O. Chidambaram Pillai, Thiru Vi Ka, Bharathidasan, M. Varadarajan, Namakkal Kavignar, Thirukkuralar V. Munusamy, Devaneya Pavanar, M. Karunanithi, and Solomon Pappaiah, besides several hundred others. The commentary by M. Varadarajan entitled Tirukkural Thelivurai (lit. Lucid commentary of the Kural), first published in 1949, remains the most published modern commentary, with more than 200 editions by the same publisher.[200]

According to K. Mohanraj, as of 2013[update], there were at least 497 Tamil language commentaries written by 382 scholars beginning with Manakkudavar from the Medieval era. Of these at least 277 scholars have written commentaries for the entire work.[201]

Translations

[edit]

The Kural has been the most frequently translated ancient Tamil text. By 1975, its translations in at least 20 major languages had been published:[203]

- Indian languages: Sanskrit, Hindi, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Bengali, Marathi, Gujarati, and Urdu

- Non-Indian languages: Burmese, Malay, Chinese, Fijian, Latin, French, German, Russian, Polish, Swedish, Thai, and English

The text was likely translated into Indian languages by Indian scholars over the centuries, but the palm leaf manuscripts of such translations have been rare. For example, S. R. Ranganathan, a librarian of University of Madras during the British rule, discovered a Malayalam translation copied in year 777 of the Malayalam calendar, a manuscript that Zvelebil dates to late 16th century.[204]

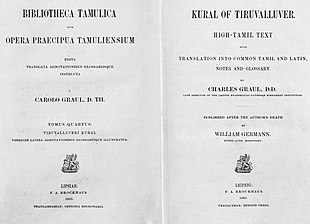

The text was translated into several European languages during the colonial era, particularly by the Christian missionaries.[205] The first European language translation was made in Latin by Constantius Joseph Beschi and was published in 1730. However, he translated only the first two books, viz., virtue and wealth, leaving out the book on love because its erotic and sexual nature was deemed by him to be inappropriate for a Christian missionary. The first French translation was brought about by an unknown author by about 1767 that went unnoticed. The first available French version was by E. S. Ariel in 1848. Again, he did not translate the whole work but only parts of it. The first German translation was made by Karl Graul, who published it in 1856 both at London and Leipzig.[202][206] Graul additionally translated the work into Latin in 1856.[29]

The first, and incomplete, English translations were made by N. E. Kindersley in 1794 and then by Francis Whyte Ellis in 1812. While Kindersley translated a selection of the Kural text, Ellis translated 120 couplets in all—69 of them in verse and 51 in prose.[207][208] E. J. Robinson's translations of part of the Kural into English were published in 1873 in his book The Tamil Wisdom and its 1885 expanded edition titled The Tales and Poems of South India, ultimately translating the first two books of the Kural text.[209][210] W. H. Drew translated the first two books of the Kural text in prose in 1840 and 1852, respectively. It contained the original Tamil text of the Kural, Parimelalhagar's commentary, Ramanuja Kavirayar's amplification of the commentary and Drew's English prose translation. However, Drew translated only 630 couplets, and the remaining were translated by John Lazarus, a native missionary, providing the first complete translation in English made by two translators. Like Beschi, Drew did not translate the third book on love.[211] The first complete English translation of the Kural by a single author was the one by the Christian missionary George Uglow Pope in 1886, which introduced the complete Kural to the western world.[212]

The translations of the Kural in Southeast Asian and East Asian languages were published in the 20th century. A few of these relied on re-translating the earlier English translations of the work.[204]

By the end of the 20th century, there were about 24 translations of the Kural in English alone, by both native and non-native scholars, including those by V. V. S. Aiyar, K. M. Balasubramaniam, Shuddhananda Bharati, A. Chakravarti, M. S. Purnalingam Pillai, C. Rajagopalachari, P. S. Sundaram, V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar, G. Vanmikanathan, Kasturi Srinivasan, S. N. Sriramadesikan, and K. R. Srinivasa Iyengar.[213] The work has also been translated into Vaagri Booli, the language of the Narikuravas, a tribal community in Tamil Nadu, by Kittu Sironmani.[214] In October 2021, the Central Institute of Classical Tamil announced its translating the Kural text into 102 world languages.[215]

As of 2024, the Kural has been translated into 57 languages, with a total of 350 individual translations, of which 143 are in English.[216]

Translational difficulties and distortions

[edit]

With a highly compressed prosodic form, the Kural text employs the intricately complex Kural venba metre, known for its eminent suitability to gnomic poetry.[217] This form, which Zvelebil calls "a marvel of brevity and condensation," is closely connected with the structural properties of the Tamil language and has historically presented extreme difficulties to its translators.[218] Talking about translating the Kural into other languages, Herbert Arthur Popley observes, "it is impossible in any translation to do justice to the beauty and force of the original."[219] After translating a good portion of the Kural text, Karl Graul stated, "No translation can convey any idea of its charming effect. It is truly an apple of gold in a net-work of silver."[29] Zvelebil claims that it is impossible to truly appreciate the maxims found in the Kural couplets through a translation but rather that the Kural has to be read and understood in its original Tamil form.[40]

Besides these inherent difficulties in translating the Kural, some scholars have attempted to either read their own ideas into the Kural couplets or deliberately misinterpret the message to make it conform to their preconceived notions. The translations by the Christian missionaries since the colonial era are often criticized for misinterpreting the text in order to conform it to Christian principles and beliefs. The Latin translation by the Christian missionary Father Beschi, for instance, contains several such mistranslations. According to V. Ramasamy, "Beschi is purposely distorting the message of the original when he renders பிறவாழி as 'the sea of miserable life' and the phrase பிறவிப்பெருங்கடல் as 'sea of this birth' which has been translated by others as 'the sea of many births'. Beschi means thus 'those who swim the vast sea of miseries'. The concept of rebirth or many births for the same soul is contrary to Christian principle and belief."[220] In August 2022, the governor of Tamil Nadu, R. N. Ravi, criticized Anglican Christian missionary G. U. Pope for "translating with the colonial objective to 'trivialise' the spiritual wisdom of India," resulting in a "de-spiritualised version" of the Kural text.[221]

According to Norman Cutler, both in the past and in the contemporary era, the Kural has been reinterpreted and fit to reflect the textual values in the text as well as the cultural values of the author(s).[222] About 1300 CE, the Tamil scholar Parimelalhagar interpreted the text in Brahmanical premises and terms.[222] Just like Christian missionaries during the colonial era cast the work in their own Christian premises, phrases and concepts, some Dravidianists of the contemporary era reinterpret and cast the work to further their own goals and socio-political values. This has produced highly divergent interpretations of the original.[222][223]

Publication

[edit]

The Tirukkuṟaḷ remained largely unknown outside India for over a millennium. As was the practice across the ancient Indian subcontinent, in addition to palm-leaf manuscripts, the Kural literature had been passed on as word of mouth from parents to their children and from preceptors to their students for generations within the Tamil-speaking regions of South India.[224] According to Sanjeevi, the first translation of the work appeared in Malayalam (Kerala) in 1595.[225][226][k]

The first paper print of the Tirukkuṟaḷ is traceable to 1812, credited to the efforts of Ñānapirakācar who used wooden blocks embossed from palm-leaf scripts to produce copies of the Tirukkuṟaḷ along with those of Nalatiyar.[227] It was only in 1835 that Indians were permitted to establish printing press. The Kural was the first book to be published in Tamil,[228] followed by the Naladiyar.[229] It is said that when Francis Whyte Ellis, a British civil servant in the Madras Presidency and a scholar of Tamil and Sanskrit who had established a Tamil sangam (academy) in Madras in 1825, asked Tamil enthusiasts to "bring to him ancient Tamil manuscripts for publication,"[230] Kandappan, the butler of George Harrington, a European civil servant possibly in the Madurai district, and the grandfather of Iyothee Thass, handed in handwritten palm-leaf manuscripts of the Kural text as well as the Tiruvalluva Maalai and the Naladiyar, which he found between 1825 and 1831 in a pile of leaves used for cooking. The books were finally printed in 1831 by Ellis with the help of his manager Muthusamy Pillai and Tamil scholar Tandavaraya Mudaliar.[230] Subsequent editions of the Tirukkuṟaḷ appeared in 1833, 1838, 1840, and 1842.[30] Soon many commentaries followed, including those by Mahalinga Iyer, who published only the first 24 chapters.[231] The Kural has been continuously in print ever since.[30] By 1925, the Kural literature had already appeared in more than 65 editions[30] and by the turn of the 21st century, it had crossed 500 editions.[232]

The first critical edition of the Tirukkaral based on manuscripts discovered in Hindu monasteries and private collections was published in 1861 by Arumuka Navalar – the Jaffna-born Tamil scholar and Shaivism activist.[233][234] Navalar, states Zvelebil, was "probably the greatest and most influential among the forerunners" in studying numerous versions and bringing out an edited split-sandhi version for the scholarship of the Kurral and many other historic Tamil texts in the 19th century.[234]

Parimelalhagar's commentary on the Tirukkuṟaḷ was published for the first time in 1840 and became the most widely published commentary ever since.[235] In 1850, the Kural was published with commentaries by Vedagiri Mudaliar, who published a revised version later in 1853.[231] This is the first time that the entire Kural text was published with commentaries.[231] In 1917, Manakkudavar's commentary for the first book of the Kural text was published by V. O. Chidambaram Pillai.[108][236] Manakkudavar commentary for the entire Kural text was first published in 1925 by K. Ponnusami Nadar.[237] As of 2013, Perimelalhagar's commentary appeared in more than 200 editions by as many as 30 publishers.[200]

Since the 1970s, the Kural text has been transliterated into ancient Tamil scripts such as the Tamil-Brahmi script, Pallava script, Vatteluttu script and others by Gift Siromoney of the International Institute of Tamil Studies at the Madras Christian College.[238][239]

Comparison with other ancient literature

[edit]

The Kural text is a part of the ancient Tamil literary tradition, yet it is also a part of the "one great Indian ethical, didactic tradition", as a few of his verses are "undoubtedly" translations of the verses in Sanskrit classics.[41] The themes and ideas in Tirukkuṟaḷ – sometimes with close similarities and sometimes with significant differences – are also found in Manu's Manusmriti (also called the Manavadharmasastra), Kautilya's Arthashastra, Kamandaka's Nitisara, and Vatsyayana's Kamasutra.[1] Some of the teachings in the Tirukkuṟaḷ, states Zvelebil, are "undoubtedly" based on the then extant Sanskrit works such as the more ancient Arthashastra and Manusmriti.[39]

According to Zvelebil, the Tirukkuṟaḷ borrows "a great number of lines" and phrases from earlier Tamil texts. For example, phrases found in Kuruntokai (lit. "The Collection of Short [Poems]") and many lines in Narrinai (lit. "The Excellent Love Settings") which starts with an invocation to Vishnu, appear in the later Tirukkuṟaḷ.[240] Authors who came after the composition of the Tirukkuṟaḷ similarly extensively quoted and borrowed from the Tirukkuṟaḷ. For example, the Prabandhas such as the Tiruvalluvamalai probably from the 10th century CE are anthologies on Tirukkuṟaḷ, and these extensively quote and embed it verses written in meters ascribed to gods, goddesses, and revered Tamil scholars.[241] Similarly, the love story Perunkatai (lit. "The Great Story") probably composed in the 9th century quotes from the Tirukkuṟaḷ and embeds similar teachings and morals.[242] Verse 22.59–61 of the Manimekalai – a Buddhist-princess and later nun based love story epic, likely written about the 6th century CE, also quotes the Tirukkuṟaḷ. This Buddhist epic ridicules Jainism while embedding morals and ideals similar to those in the Kural.[243]

The Tirukkuṟaḷ teachings are similar to those found in Arthasastra but differ in some important aspects. In Valluvar's theory of state, unlike Kautilya, the army (patai) is the most important element. Valluvar recommends that a well kept and well-trained army (patai) led by an able commander and ready to go to war is necessary for a state.[145]

According to Hajela, the Porul of the Kural text is based on morality and benevolence as its cornerstones.[244] The Tirukkuṟaḷ teaches that the ministers and people who work in public office should lead an ethical and moral life.[142] Unlike the Manusmriti, the Kural does not give women a lowly and dependent position but are rather idealised.[140] The Tirukkuṟaḷ also does not give importance to castes or any dynasty of rulers and ministers. The text states that one should call anyone with virtue and kindness a Brahmin.[245]

World literature

[edit]Scholars compare the teachings in the Tirukkuṟaḷ with those in other ancient thoughts such as the Confucian sayings in Lun Yu, Hitopadesa, Panchatantra, Manusmriti, Tirumandiram, Book of Proverbs in the Bible, sayings of the Buddha in Dhammapada, and the ethical works of Persian origin such as Gulistan and Bustan, in addition to the holy books of various religions.[246]

The Kural text and the Confucian sayings recorded in the classic Analects of Chinese (called Lun Yu, meaning "Sacred Sayings") share some similarities. Both Valluvar and Confucius focused on the behaviors and moral conducts of a common person. Similar to Valluvar, Confucius advocated legal justice embracing human principles, courtesy, and filial piety, besides the virtues of benevolence, righteousness, loyalty and trustworthiness as foundations of life.[247] While ahimsa or non-violence remains the fundamental virtue of the Valluvarean tradition, Zen remains the central theme in Confucian tradition.[16][248] Incidentally, Valluvar differed from Confucius in two respects. Firstly, unlike Confucius, Valluvar was also a poet. Secondly, Confucius did not deal with the subject of conjugal love, for which Valluvar devoted an entire division in his work.[249] Child-rearing is central to the Confucian thought of procreation of humanity and the benevolence of society. The Lun Yu says, "Therefore an enlightened ruler will regulate his people's livelihood so as to ensure that, above they have enough to serve their parents and below they have enough to support their wives and children."[250][l]

Reception

[edit]The Kural text has historically received highly esteemed reception from virtually every section of the society. Many post-Sangam and medieval poets have sung in praise of the Kural text and its author. Avvaiyar praised Valluvar as the one who pierced an atom and injected seven seas into it and then compressed it and presented it in the form of his work, emphasizing on the work's succinctness.[26][251][252] The Kural remains the only work that has been honored with an exclusive work of compiled paeans known as the Tiruvalluva Maalai in the Tamil literary corpus, attributed to 55 different poets, including legendary ones.[26] All major Indian religions and sects, including Shaivism, Vaishnavism, Jainism, and Buddhism, have greatly celebrated the Kural text, many of which incorporated Kural's teachings in both their religious and non-religious works, including the Silappathikaram, Manimekalai, Tirumurai, Periya Puranam, and Kamba Ramayanam.[253]

The Kural has been widely acknowledged within and outside India for its universal, non-denominational values.[126][251] The Russian philosopher Alexander Piatigorsky called it chef d'oeuvre of both Indian and world literature "due not only to the great artistic merits of the work but also to the lofty humane ideas permeating it which are equally precious to the people all over the world, of all periods and countries."[254] G. U. Pope called its author "a bard of universal man" for being a generalist and universal.[83][255] According to Albert Schweitzer, "there hardly exists in the literature of the world a collection of maxims in which we find so much of lofty wisdom."[251][256] Leo Tolstoy called it "the Hindu Kural" and recommended it to Mahatma Gandhi.[257][258] Mahatma Gandhi called it "a textbook of indispensable authority on moral life" and went on to say, "The maxims of Valluvar have touched my soul. There is none who has given such a treasure of wisdom like him."[251]

"I wanted to learn Tamil, only to enable me to study Valluvar's Thirukkural through his mother tongue itself ... Only a few of us know the name of Thiruvalluvar. The North Indians do not know the name of the great saint. There is no one who has given such treasure of wisdom like him." ... "It is a text-book of indispensable authority on moral life. The maxims of Valluvar have touched my soul."

— Mahatma Gandhi[259]

Jesuit, Catholic and Protestant missionaries in colonial-era South India have highly praised the text, many of whom went on to translate the text into European languages. The Protestant missionary Edward Jewitt Robinson said that the Kural contains all things and there is nothing which it does not contain.[251] The Anglican missionary John Lazarus said, "No Tamil work can ever approach the purity of the Kural. It is a standing repute to modern Tamil."[251] According to the American Christian missionary Emmons E. White, "Thirukkural is a synthesis of the best moral teachings of the world."[251]

The Kural has also been exalted by leaders of political, spiritual, social, ethical, religious and other domains of the society since ancient times. Rajaji commented, "It is the gospel of love and a code of soul-luminous life. The whole of human aspiration is epitomized in this immortal book, a book for all ages."[251] According to K. M. Munshi, "Thirukkural is a treatise par excellence on the art of living."[251] The Indian nationalist and Yoga guru Sri Aurobindo stated, "Thirukkural is gnomic poetry, the greatest in planned conception and force of execution ever written in this kind."[251] E. S. Ariel, who translated and published the third part of the Kural to French in 1848, called it "a masterpiece of Tamil literature, one of the highest and purest expressions of human thought."[47] Zakir Hussain, former President of India, said, "Thirukkural is a treasure house of worldly knowledge, ethical guidance and spiritual wisdom."[251]

Inscriptions and other historical records

[edit]The Tirukkuṟaḷ remained the chief administrative text of the Kongu Nadu region of the medieval Tamil land.[260] Kural inscriptions and other historical records are found across Tamil Nadu. The 15th-century Jain inscriptions in the Ponsorimalai near Mallur in Salem district bear couplet 251 from the "Shunning meat" chapter of the Kural text, indicating that the people of the Kongu Nadu region practiced ahimsa and non-killing as chief virtues.[261] Other inscriptions include the 1617 CE Poondurai Nattar scroll in Kongu Nadu, the 1798 CE Palladam Angala Parameshwari Kodai copper inscriptions in Naranapuram in Kongu Nadu, the 18th-century copper inscriptions found in Kapilamalai near Kapilakkuricchi town in Namakkal district, Veeramudiyalar mutt copper inscriptions in Palani, Karaiyur copper inscription in Kongu Nadu, Palaiyakottai records, and the 1818 Periya Palayathamman temple inscriptions by Francis Ellis at Royapettah in Chennai.[262]

In popular culture

[edit]

Various portraits of Valluvar have been drawn and used by the Shivaite and Jain communities of Tamil Nadu since ancient times. These portraits appeared in various poses, with Valluvar's appearance varying from matted hair to fully shaven head. The portrait of Valluvar with matted hair and a flowing beard, as drawn by artist K. R. Venugopal Sharma in 1960, was accepted by the state and central governments as an official version.[263] It soon became a popular and the most ubiquitous modern portrait of the poet.[160] In 1964, the image was unveiled in the Indian Parliament by the then President of India Zakir Hussain. In 1967, the Tamil Nadu government passed an order stating that the image of Valluvar should be present in all government offices across the state of Tamil Nadu.[264][m]

The Kural does not appear to have been set in music by Valluvar. However, a number of musicians have set it to tune and several singers have rendered it in their concerts. Modern composers who have tuned the Kural couplets include Mayuram Viswanatha Sastri and Bharadwaj. Singers who have performed full-fledged Tirukkuṟaḷ concerts include M. M. Dandapani Desikar and Chidambaram C. S. Jayaraman.[265] Madurai Somasundaram and Sanjay Subramanian are other people who have given musical rendering of the Kural. Mayuram Vishwanatha Shastri set all the verses to music in the early 20th century.[266] In January 2016, Chitravina N. Ravikiran set the entire 1330 verses to music in a record time of 16 hours.[265][267]

In 1818, the then Collector of Madras Francis Whyte Ellis issued a gold coin bearing Valluvar's image.[268][n][o] In the late 19th century, the South Indian saint 'Vallalar' Ramalinga Swamigal taught the Kural's message by conducting regular Kural classes to the masses.[231] In 1968, the Tamil Nadu government made it mandatory to display a Kural couplet in all government buses. The train running a distance of 2,921 kilometers between Kanyakumari and New Delhi is named by the Indian Railways as the Thirukural Express.[269]

The Kural is part of Tamil people's everyday life across the global Tamil diaspora. K. Balachander's Kavithalayaa Productions opened its films with the very first couplet of the Kural sung in the background.[265] Kural's phrases and ideas are found in numerous songs of Tamil movies.[270] Several Tirukkuṟaḷ conferences were conducted in the twentieth century, such as those by Tirukkural V. Munusamy in 1941[271] and by Periyar E. V. Ramasamy in 1949.[272] These were attended by several scholars, celebrities and politicians.[273] The Kural's couplets and thoughts are also widely employed in visual arts,[274][275] music,[265] dance,[276] street shows,[277] recitals,[278][279] activities,[280] and puzzles and riddles.[281] The couplets are frequently quoted by various political leaders even in pan-Indian contexts outside the Tamil diaspora, including Ram Nath Kovind,[282] P. Chidambaram,[283] and Nirmala Sitaraman.[283][284] When Jallikattu aficionados claimed that the sport is only to demonstrate the "Tamil love for the bull", the then Indian Minister of Women and Child Development Maneka Gandhi denied the claim citing that the Tirukkural does not sanction cruelty to animals.[285][286] The Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has quoted the couplets on several occasions,[287] including his recital to the Indian armed forces in 2020.[288] The Kural literature is one of the ancient texts from which the Economic Survey of India, the official annual report of the state of India's economy, draws heavy references.[289][290][291]

Temples and memorials

[edit]The Kural text and its author have been highly venerated over the centuries. In the early 16th century, the Shaiva Hindu community built a temple within the Ekambareeswara-Kamakshi (Shiva-Parvati) temple complex in Mylapore, Chennai, in honor of the Tirukkuṟaḷ's author, Valluvar.[59] The locals believe that this is where Valluvar was born, underneath a tree within the shrine's complex. A Valluvar statue in yoga position holding a palm leaf manuscript of the Tirukkuṟaḷ sits under the tree.[59] In the shrine dedicated to him, Valluvar's wife Vasukiamma is patterned after the Hindu deity Kamakshi inside the sanctum. The temple shikhara (spire) above the sanctum shows scenes of Hindu life and deities, along with Valluvar reading his couplets to his wife.[59] The sthala vriksham (holy tree of the temple) at the temple is the oil-nut or iluppai tree under which Valluvar is believed to have been born.[293] The temple was extensively renovated in the 1970s.[294]

Additional Valluvar shrines in South India are found at Tiruchuli,[295][296] Periya Kalayamputhur, Thondi, Kanjoor Thattanpady, Senapathy, and Vilvarani.[297] Many of these communities, including those in Mylapore and Tiruchuli, consider Valluvar as the 64th Nayanmar of the Saivite tradition and worship him as god and saint.[295][298]

In 1976, Valluvar Kottam, a monument to honor the Kural literature and its author, was constructed in Chennai.[292] The chief element of the monument includes a 39-metre-high (128 ft) chariot, a replica of the chariot in the temple town of Thiruvarur, and it contains a life-size statue of Valluvar. Around the chariot's perimeter are marble plates inscribed with Tirukkuṟaḷ couplets.[292] All the 1,330 verses of the Kural text are inscribed on bas-relief in the corridors in the main hall.[299]

Statues of Valluvar have been erected across the globe, including the ones at Kanyakumari, Chennai, Bengaluru, Pondicherry, Vishakapatnam, Haridwar, Puttalam, Singapore, London and Taiwan.[300][301] The tallest of these is the 41-metre (133 ft) stone statue of Valluvar erected in 2000 atop a small islet in the town of Kanyakumari on the southernmost tip of the Indian peninsula, at the confluence of the Bay of Bengal, the Arabian Sea, and the Indian Ocean.[302] This statue is currently India's 25th tallest. A life-size statue of Valluvar is one among an array of statues installed by the Tamil Nadu government on the stretch of the Marina Beach.[303]

Legacy

[edit]

The Kural remains one of the most influential Tamil texts admired by generations of scholars.[225] The work has inspired Tamil culture and people from all walks of life, generating parallels in the literature of various languages within the Indian subcontinent.[304] Its translations into European languages starting from the early 18th century made the work known globally.[305] Authors influenced by the Kural include Ilango Adigal, Seethalai Satthanar, Sekkilar, Kambar, Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, Albert Schweitzer, Ramalinga Swamigal, E. S. Ariel, Constantius Joseph Beschi, Karl Graul, August Friedrich Caemmerer, Nathaniel Edward Kindersley, Francis Whyte Ellis, Charles E. Gover, George Uglow Pope, Vinoba Bhave, Alexander Piatigorsky, A. P. J. Abdul Kalam, and Yu Hsi. Many of these authors have translated the work into their languages.[305][306]

The Kural is an oft-quoted Tamil work.[29] Classical Tamil works such as the Purananuru, Manimekalai, Silappathikaram, Periya Puranam, and Kamba Ramayanam all cite the Kural by various names, bestowing numerous titles to the work that was originally untitled by its author.[253] Kural couplets and thoughts are cited in 32 instances in the Purananuru, 35 in Purapporul Venba Maalai, 1 each in Pathittrupatthu and the Ten Idylls, 13 in the Silappathikaram, 91 in the Manimekalai, 20 in Jivaka Chinthamani, 12 in Villi Bharatham, 7 in Thiruvilaiyadal Puranam, and 4 in Kanda Puranam.[307] In Kamba Ramayanam, poet Kambar has used Kural ideas in as many as 600 instances.[308][309] The work is commonly quoted in vegetarian conferences, both in India and abroad,[310][311] and is frequently cited on social media and online forums involving discussions on the topics of animal rights, non-killing, and shunning meat.[312]

The Kural text was first included in the school syllabus by the colonial-era British government.[313] However, only select 275 couplets had been taught to the schoolchildren from Standards III through XII.[314] Attempts to include the Kural literature as a compulsory subject in schools were ineffective in the decades following Indian Independence.[315] On 26 April 2016, the Madras High Court directed the Tamil Nadu state government to include all the 108 chapters of the Books of Aram and Porul of the Kural text in school syllabus for classes VI through XII from the academic year 2017–2018 "to build a nation with moral values."[315][316] The court further observed, "No other philosophical or religious work has such moral and intellectual approach to problems of life."[317]

The Kural is believed to have inspired many, including Mahatma Gandhi, to pursue the path of ahimsa or non-violence.[318] Leo Tolstoy was inspired by the concept of non-violence found in the Kural when he read a German version of the book, who in turn instilled the concept in Mahatma Gandhi through his A Letter to a Hindu when young Gandhi sought his guidance.[251][257][319] Gandhi then took to studying the Kural in prison, which eventually culminated in his starting the non-violence movement to fight against the ruling British government.[26] The 19th-century poet-saint 'Vallalar' Ramalinga Swamigal was inspired by the Kural at a young age, who then spent his life promoting compassion and non-violence, emphasizing on non-killing and meatless way of life.[306][320]

See also

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Jain philosophy |

|---|

|

| Concepts |

|

| People |

|

| Part of a series on | |

| Hindu philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Orthodox | |

| | |

| Heterodox | |

| | |

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern philosophy |

|---|

| |

Notes