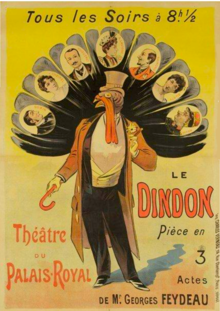

Le Dindon

Le Dindon is a three-act farce by Georges Feydeau, first produced in Paris in 1896. It depicts the unsuccessful attempts of the central character – the "dindon" (roughly "the fall guy") to seduce a married woman, and the chaotic events caused by his fruitless machinations.

Background and premiere

[edit]By the mid-1890s Georges Feydeau had established himself as the leading writer of French farce of his generation. At a time when a run of 100 performances was regarded in Parisian theatres as a success,[1] Feydeau had enjoyed runs of 434 for Champignol malgré lui (1892) and 371 for L'Hôtel du libre échange (1894). Both those plays had been written in collaboration with Maurice Desvallières. Le Dindon was a solo effort.[2]

The play opened at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal on 8 February 1896, and ran for 238 performances.[3]

The title of the play has no exact English equivalent in the context in which Feydeau uses it. The Dictionnaire de l'Académie française, in addition to the general meaning – "turkey", as in poultry – offers subsidiary definitions of "dindon": "un homme niais et infatué de lui-même … le dindon de la farce … la dupe, la victime d'une plaisanterie ou d'une intrigue" – "a silly, self-infatuated man … the turkey of the farce … the dupe, the victim of a joke or an intrigue."[4]

Original cast

[edit]- Pontagnac – Félix Huguenet

- Vatelin – Charles Constant Gobin

- Rédillon – Perrée Raimond

- Soldignac – Gaston Dubosc

- Pinchard – Édouard Maugé

- Gérome – Émile Francès

- Jean – Mori

- Victor – Louis Dean

- Le Gérant – Émile Garandet

- First policeman – Colombet

- Second policeman – Garon

- Lucienne Vatelin – Jeanne Cheirel

- Clotilde Pontagnac – Andrée Mégard

- Maggy Soldignac – Alice Lavigne

- Mme Pinchard – Élisa Louise Bilhaut

- Armandine – Maris Burty

- Clara – Narlay

- Source: Les Archives du spectacle.[5]

Plot

[edit]Act 1

[edit]The scene is the drawing-room of the Paris residence of the Vatelins. Pontagnac, although married to a beautiful wife, is a rake who obsessively pursues women. In pursuit of the highly respectable Mme Lucienne Vatelin he intrudes into her drawing room and becomes so pressing that she calls for her husband. Vatelin recognises Pontagnac as one of his club friends; an explanation follows, and Pontagnac apologises profusely, but is still powerfully attracted to Lucienne. She tells him that he is wasting his time pursuing her: she is devoted to Vatelin and as long as he is faithful to her, she will be faithful to him. Moreover, in the unlikely event that Vatelin should ever stray, she has her own preferred candidate as partner in her revenge, a nice young man called Rédillon, whom she finds attractive, despite his red beard.[6]

Pontagnac's wife, Clotilde, holds views similar to those of her friend Lucienne: if ever she catches her husband straying, she will take her revenge with an attractive young man. It happens that the young man she has in mind is Rédillon. Pontagnac is unaware of this. Vatelin, though no Adonis – he is short and tubby – is the unwilling object of the passionate devotion of Madame Meggy Soldignac. She is an Englishwoman whom he met while in London on business. She has pursued him to Paris, and threatens to kill herself unless he consents to meet her at the Ultimus Hotel. He reluctantly agrees. Pontagnac, learning of this, sees Vatelin's liaison as his opportunity to overcome Lucienne's resistance.[7]

Act 2

[edit]

The scene is Room 39 of the Ultimus Hotel. The room that Meggy has reserved is much in demand, and is double-booked in error. It is occupied in rapid succession by Rédillon and an attractive cocotte, Armandine, and then by Major Pinchard – an army surgeon – and his wife, who is deaf. The latter, being unwell, goes to bed, while the major leaves the room to prepare a hot poultice for her. Vatelin enters stealthily, and gets into the bed, where he supposes Meggy is expecting him. Immediately electric bells ring at terrific volume. Pontagnac, who is lying in wait with Lucienne in the adjoining room to witness her husband's misconduct, has placed an apparatus under the mattress to trigger the bells. The room becomes the scene of chaos, the major applies the hot poultice to Vatelin by mistake, vengeful spouses, including Meggy's, come and go, and a brawl ensues when two different policemen attempt to arrest Pontagnac for improper conduct.[8]

Act 3

[edit]Lucienne calls on Rédillon at his bachelor flat, intending to get him into bed to revenge herself on her husband, but Rédillon is too fatigued from his demanding nocturnal activities with Armandine. Clotilde arrives, on the same mission as Lucienne, but Rédillon cannot oblige. Pontagnac arrives in pursuit of Lucienne and is ignored. Vatelin enters, followed by a policeman whom he wants to witness an adultery in flagrante delicto. Vatelin confesses to Rédillon that he is still in love with his wife and, when he learns that nothing has happened between the alleged lovers, he sobs with relief and pleasure. Lucienne overhears and falls into her husband's arms. Everyone is content, except for Pontagnac, who realises that he himself is the "dindon" – the "fall guy".[9]

Reception

[edit]The critics were enthusiastic. One wrote, "The hilarious qualities of this side-splitting farce are enormous; it kept the house in a continual roar, especially during the second act, which is indescribably droll".[10] Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique called the piece "a joyous farce" and praised Feydeau's comic invention.[11]

When the play has been revived in more recent times it has had favourable views. Reviewing the 1959 production by the Comédie-Française, Philip Hope-Wallace called it "the apogee of bedroom farce of its kind, and a pure delight" and rated the frenetic middle act superior even to the funniest scenes in Occupe-toi d'Amélie!.[12] When the production was seen in New York two years later, John Chapman of The Daily News called the play "a masterpiece of farce" and wished that every director in the US could see the production.[13] The director Peter Hall observed in 1994, "Le Dindon ... is the most elegantly complex of his plays. By the end of each act, every character is spinning dizzily in a surreal climax of complications. … There is no one funnier than Feydeau in European drama, but there is equally no one who makes us look so unblinkingly at our basic selves."[14]

Revivals and adaptations

[edit]The play was revived in Paris in 1912, at the Théâtre du Vaudeville, where it ran for 98 performances.[15] In 1951 the Comédie-Française took the piece into its repertoire, and revived the production 16 times over the next 20 years, with the central role of Pontagnac played by Jacques Charon, Jean Piat, Jean-Paul Roussillon and in some later runs, the author's grandson, Alain Feydeau.[16]

Translations and adaptations in English have been given various titles, including There's One in Every Marriage, 1970;[17] Sauce for the Goose, 1974;[18] Paying the Piper, 1975;[19] Ruling the Roost, 1980;[20] and An Absolute Turkey, 1994.[21] The off-Broadway Pearl Theatre in New York staged the play in 2016 under the title The Dingdong.[22]

A 1951 film with the same title was made by the director Claude Barma, with Charon as Pontagnac.[23] Jalil Lespert made another adaptation in 2019.[24]

References and sources

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Edmond Audran", Opérette – Théâtre Musical, Académie Nationale de l'Opérette. Retrieved 29 July 2020

- ^ Noël and Stoullig (1893), p. 278; (1894), p. 410; (1895), p. 363; and (1896), p. 260

- ^ Stoullig (1897), p. 248

- ^ "Dindon", Dictionnaire de l'Académie française, 9e édition. Retrieved 3 August 2020

- ^ "Le Dindon", Les Archives du spectacle. Retrieved 7 August 2020

- ^ Feydeau, p. 223

- ^ Feydeau, p. 224

- ^ Feydeau, pp. 224–226

- ^ Feydeau, pp. 226–227

- ^ "The Drama in Paris", The Era, 15 February 1896, p. 13

- ^ Stoullig (1897), p. 241

- ^ Hope-Wallace, Philip. "Farce in best tradition", The Manchester Guardian, 17 March 1959, p. 5

- ^ Chapman, John. "An Old French Farce Comes Happily Alive", The Daily News, 9 March 1961, p. 65

- ^ Hall, Peter. "Everyday truth of frantic French farce", The Guardian, 3 January 1994, p. 24

- ^ Stoullig (1913), p. 206

- ^ "Le Dindon", Les Archives du spectacle. Retrieved 7 August 2020

- ^ There's One in Every Marriage, WorldCat OCLC 317851270

- ^ Sauce for the Goose, WorldCat OCLC 560303152

- ^ "Books", The Stage, 30 January 1975, p. 10

- ^ Ruling the Roost, WorldCat OCLC 627069780

- ^ An Absolute Turkey, WorldCat OCLC 820557034

- ^ "Review: The Dingdong" by Victor Gluck, theaterscene.net, 29 April 2016

- ^ Travers, James. Le Dindon (1951), frenchfilms.org. Retrieved 7 August 2020

- ^ Le Dindon (2019) at IMDb

Sources

[edit]- Feydeau, Georges (2008). Le Dindon. Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 978-2-07-041290-7.

- Noël, Édouard [in French]; Edmond Stoullig [in French] (1893). Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique, 1892. Paris: Charpentier. OCLC 172996346. (Online – via BnF Gallica)

- Noël, Édouard; Edmond Stoullig (1894). Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique, 1893. Paris: Charpentier. OCLC 172996346.

- Noël, Édouard; Edmond Stoullig (1895). Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique, 1894. Paris: Charpentier. OCLC 172996346.

- Noël, Édouard; Edmond Stoullig (1896). Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique, 1895. Paris: Charpentier. OCLC 172996346.

- Noël, Édouard; Edmond Stoullig (1897). Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique, 1896. Paris: Charpentier. OCLC 172996346.

- Stoullig, Edmond (1898). Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique, 1897. Paris: Charpentier. OCLC 172996346.

- Stoullig, Edmond (1913). Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique, 1912 (in French). Paris: Ollendorff. OCLC 172996346.