Lost Forest Research Natural Area

| Lost Forest Research Natural Area | |

|---|---|

Isolated pines forest environment | |

Lost Forest in south central Oregon | |

| Location | Lake County, Oregon, United States |

| Nearest city | Christmas Valley, Oregon |

| Coordinates | 43°23′N 120°20′W / 43.38°N 120.33°W[1] |

| Area | 8,960 acres (36.3 km2) |

| Established | 1972 |

| Governing body | Bureau of Land Management |

The Lost Forest Research Natural Area is a designated forest created by the Bureau of Land Management to protect an ancient stand of ponderosa pine in the remote high desert county of northern Lake County, in the south central area of the U.S. state of Oregon. Lost Forest is an isolated area of pine trees separated from the nearest contiguous forest land by forty miles of arid desert. There are no springs or surface water in Lost Forest, and much of the southwest portion of the natural area is covered by large shifting sand dunes that are slowly encroaching on the forest.

Geology

[edit]Lost Forest is located at the northeastern corner of the Christmas Lake Basin in south central Oregon. The bedrock beneath the area was created by basalt flows laid down during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs. After a period of intense faulting during the middle Pleistocene, a large basin area was created by erosion and sedimentation. This basin filled with water during the wet climatic periods of the Pleistocene and post-Pleistocene. Over the past 3,200 years, the surface water in the Christmas Lake Basin has completely dried up, leaving an arid high desert environment.[2]

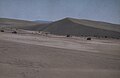

Today, the Lost Forest area is generally flat with gentle swales. The base elevation is 4,400 feet (1,300 m) above sea level. However, there are a number of basalt outcroppings that rise 100 to 230 feet (30 to 70 m) above the surrounding terrain. There are also large moving sand dunes in the southwest corner of the natural area. These dunes are made up of lacustrine sediments, Aeolian deposits, and alluvial materials with large amounts of volcanic pumice and ash mixed into fine sand.[3] Most of the dunes occurred west and south of the Lost Forest; however, there has been some shifting of sand from the dry lakebed of Fossil Lake through portions of the pine and juniper stands in the southwest section of the natural area. Some trees have been killed and others partially covered and then uncovered later as the sand moved through the area. While the dunes kill some trees, they do not appear to threaten the forest in general.[4]

Environment

[edit]

Lost Forest covers approximately 9,000 acres (36 km2). It is a self-sustaining stand of ponderosa pines growing in the arid high desert, 40 miles (64 km) from the nearest contiguous pine forest. The Bureau of Land Management considers 4,153 acres (1,681 ha) to be prime forest land with large old-growth trees dominating the stands. Lost Forest is a remnant of an ancient ponderosa pine forest that covered much of central Oregon thousands of years ago, when the climate was cooler and wetter. Today, the Lost Forest pines survive on half the annual precipitation normally required for their species. This is possible because of the unique soil and hydrologic properties of the Lost Forest area.[4][5][6][7]

The natural area's deep sandy soil has helped the Lost Forest ponderosa pines survive in the arid high desert environment. The Lost Forest soil was formed from lake sediments and alluvial materials. Pumice sands from Mount Mazama and Newberry Crater appear in the surface soils throughout the Lost Forest area. The post-Pleistocene lake environment formed the ash sediments from Mount Mazama into porous ground soil. The soils are underlain by hard calcium carbonate caliche layer several inches thick. This subsurface layer is impervious to water drainage and is seldom penetrated by roots. As a result, ground water is held near the surface. The local ponderosa pines make use the moisture held in the porous soil above the caliche barrier. In addition, scientists have found that the pine seeds from the Lost Forest trees germinated more quickly than other ponderosa pine seeds, suggesting a local adaptation to the arid environment is now a common characteristic of the Lost Forest ponderosa pine community.[2][7]

In addition to its ponderosa pines, the Lost Forest also supports a plant community that includes big sagebrush, antelope bitterbrush, and other shrubs as well as a number of desert grasses and flowering plants. Western juniper are also common in many parts of the natural area.[2][3]

Ponderosa pines dominate the Lost Forest Research Natural Area, typically growing in open stands rooted in sandy soils. In some parts of the natural area, western junipers are sparse, covering less than one percent of the land. However, much of Lost Forest is characterized by co-dominance of ponderosa pine and western juniper. Some of the older junipers are very large. One specimen is the largest known western juniper in Oregon, reaching a height of 68 feet (21 m). Bark beetle attacks and drought in the 1920s and the 1930s resulted in high juniper mortality from which the population has not fully recovered.[2][4]

- Basalt outcropping

- Mixed pine and juniper

- Lost Forest outskirts

- Lost Forest dunes

Understory shrubs are dense in some areas, sparse in other areas, and entirely absent in areas where sand dunes have encroached on the forest. The most abundant large shrub species are large sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata), antelope bitterbrush (Purshia tridentata), and yellow rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus). Among the smaller shrubs little sagebrush (Artemisia arbuscula), spreading phlox (Phlox diffusa), granite prickly phlox (Linanthus pungens), and littleleaf horsebrush (Tetradymia glabrata) are common. Curl-leaf mountain mahogany (Cercocarpu ledifolius) is found on some of the basalt outcroppings. There are a number of perennial grasses common throughout the Lost Forest. These include Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), Sandberg bluegrass (Poa secunda), Thurber's needlegrass (Achnatherum thurberianum), needle and thread grass (Hesperostipa comata), Indian ricegrass (Oryzopsis hymenoides), bottlebrush squirreltail (Elymus elymoides), and crested wheatgrass (Agropyron cristatum). Perennial flowering plants found in the natural area include lupin (Lupinus), cushion buckwheat (Eriogonum ovalifolium), lemon scurf-pea (Psoralea lanceolata), common wooly sunflower (Eriophyllum lanatum), and Townsend daisy (Townsendia florifer).[2]

Wildlife

[edit]The animal population is limited by the size and isolation of the Lost Forest area. However, there is still a wide range of native animals present in the natural area. The larger mammals include mule deer, pronghorn, badger, gray fox, red fox, coyotes, bobcat, and cougar. Among the smaller animals, black-tailed jackrabbit, pygmy rabbit, mountain cottontail, long-tailed weasel, and porcupines are all found in Lost Forest. Rodents include yellow-pine chipmunks, least chipmunks, Townsend's ground squirrels, Ord's kangaroo rats, bushy-tailed woodrats, Great Basin pocket mice, deer mice, western harvest mice, northern grasshopper mice, and northern pocket gophers. There also thirteen bat species that live in or near Lost Forest.[2]

Lost Forest is home to a number of bird species as well. They include pinyon jay, black-billed magpie, red-shafted flicker, Brewer's blackbird, American robin, mountain bluebird, western tanager, sage sparrow, loggerhead shrike, and sapsucker. There are also birds of prey such as prairie falcon, red-tailed hawks, and golden eagles.[2]

Human use

[edit]The first settlers arrived in the Christmas Lake Valley around 1865. However, it was not until around 1906 that large numbers of settlers began to homestead in the area. The settlers cleared the land of sagebrush for farming, and used the pine and juniper in Lost Forest to construct houses, corrals, and farm buildings. Wood from the forest was also used for heating and cooking. The Lost Forest area was also used for grazing sheep, cattle, and horses. Due to the harsh high desert conditions, most of the settlers had abandoned their homesteads by the early 1920s. A prolonged drought in the 1920s and 1930s put an end to dry farming in the region.[2]

Some irrigated farming continued in Christmas Lake Valley, usually as part of a larger cattle ranching operation. Lost Forest is part of the View Point Ranch grazing allotment; however, lack of water kept grazing on that unit to a minimum. Nevertheless, grazing did have a long-term impact on the vegetation. For example, bluebunch wheatgrass which is good for grazing is now extremely rare in Lost Forest while it is a very common plant in ungrazed areas of central Oregon. No grazing has occurred in Lost Forest since about 1968.[2]

During World War II, the Christmas Lake Valley including Lost Forest was used for military training exercises. Military units from Camp Abbot bivouacked and conducted battle maneuvers throughout the area. This activity was particularly intense in 1943 during the Oregon Maneuver, involving over 100,000 army troops.[2][8][9]

The Bureau of Land Management authorized timber sales in 1949 and 1955 to remove trees that were vulnerable to insects and disease. A total of 522,000 board feet (1,230 m3) were cut in 1949, and another 1,599,000 board feet (3,770 m3) were removed in 1955. The site of a portable milling operation is in the area. After the logging was done, slash was piled and burned. The mill site and logged areas were seeded with crested wheatgrass.[2][4]

In 1972, the Lost Forest Research Natural Area was established by the Bureau of Land Management in order to preserve the unique ponderosa pine environment and associated vegetation and wildlife. In 1983, the Bureau of Land Management joined Lost Forest, the neighboring Christmas Valley Sand Dunes, and Fossil Lake into a single Area of Critical Environmental Concern. In 1989, the Lost Forest was designated as an Instant Wilderness Study Area, which increased the area's protection. Nevertheless, off-road vehicle use in the area around Lost Forest remains a concern. The Bureau of Land Management is assessing the impact on the natural areas and considering how off-road activities can be effectively controlled.[2][4]

Research history

[edit]Lost Forest offers the opportunity to study isolated plant and animal populations in a unique environment. As a result, researchers have been looking at various aspects of the Lost Forest for well over one hundred years. Early settlement patterns, geology, and natural resources of Lost Forest and Christmas Lake Valley were initially documented in 1884, 1889, and 1908. In 1937, analysis of tree rings highlighted long-term climatic changes that have occurred in the region. Additional tree ring studied were conducted in 1938 and 1964 expanded that knowledge. The sedimentary geology of nearby Fossil Lake was studied in 1942, 1945, and 1954. The area's fossil birds were described in a 1946 study. Two studies in the mid-1940s, found some evidence of prehistoric man in areas around Lost Forest. In 1963, the Bureau of Land Management conducted a comprehensive study of Lost Forest vegetation. That study also included soil descriptions and noted unique aspects of ponderosa pine reproductive physiology. Another vegetation study was conducted in 1973, and a health assessment of ponderosa pine stands in the Lost Forest was completed in 2007. Today, a number of studies in the Lost Forest Research Natural Area are on-going.[2]

Location

[edit]The Lost Forest Research Natural Area is located in a very remote area of northern Lake County, Oregon. It is approximately 65 miles southeast of Bend and 80 miles north of Lakeview in straight-line distance. The small unincorporated community of Christmas Valley is 26 miles from the natural area on rough desert roads. From Christmas Valley, visitors travel east on the Christmas Valley-Wagontire Road for 8 miles to the second cattle guard. Turn north and follow the rough dirt road 8 miles to a T-intersection. At the intersection, turns east. The entrance to Lost Forest is approximately 10 miles from the intersection.[2]

Inside the natural area vehicles must stay on existing roads, in order to prevent damage to tree roots and to avoid soil disturbance. Within the natural area, camping is permitted in designated sites only. Camp sites are very primitive and there is no water available in Lost Forest.[5][6]

References

[edit]- ^ "Lost Forest Research Natural Area". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Moir, William H., Jerry F. Franklin, and Chris Maser, Lost Forest Research Natural Area, Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, United States Forest Service, Department of Agriculture, Portland, Oregon, 1973.

- ^ a b "Lost Forest Research Natural Area" Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, Research Natural Areas, Lakeview District, Bureau of Land Management, United States Department of Interior, Lakeview, Oregon, 24 May 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Chadwick, Kristen L. and Andris Eglitis, Health Assessment of the Lost Forest Research Natural Area, Central Oregon Service Center for Insects and Diseases, United States Forest Service, United States Department of Agriculture, Bend, Oregon, February 2007.

- ^ a b Lost Forest Research Natural Area, Christmas Valley Sand Dunes Area of Critical Environmental Concern, Lakeview District, Bureau of Land Management, United States Department of Interior, Lakeview, Oregon, 2005.

- ^ a b "The Lost Forest, OR", Outback Scenic Byway, National Scenic Byway Program, United States Department of Transportation, Washington, D.C., 2009.

- ^ a b Jackman, E.R. and R.A. Long, The Oregon Desert, Caxton Press, Caldwell, Idaho, 1964 (Fourteenth printing May 2003), pp. 364-365.

- ^ Morehouse, Kenyon, "Camp Abbot", video interview for Oregon at War, part of the Oregon Experience series, Oregon Public Broadcasting (in cooperation with the Oregon Historical Society), Portland Oregon, 2007.

- ^ Senate Bill 449 Archived 2011-06-11 at the Wayback Machine, 75th Oregon Legislative Assembly, Salem, Oregon, 2009.