Operation Faustschlag

| Operation Faustschlag | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War I | |||||||||

Austro-Hungarian troops enter Kamianets-Podilskyi, Western Ukraine with the city's iconic castle in the background | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| | | ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 53 divisions | Unknown | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown | 63,000 captured 2,600 guns and 5,000 machine guns[1] | ||||||||

The Operation Faustschlag ("Operation Fist Punch"), also known as the Eleven Days' War,[2][3] was a Central Powers offensive in World War I. It was the last major offensive on the Eastern Front.

Russian forces were unable to put up any serious resistance due to the turmoil of the Russian Revolution and subsequent Russian Civil War. The armies of the Central Powers therefore captured huge territories in Estonia, Latvia, Belarus, and Ukraine, forcing the Bolshevik government of Russia to sign the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

Background

[edit]After the February Revolution (March 1917) brought down the Tsarist monarchy of the Russian Empire, the Imperial Russian Army was turned into the Russian Army. While vowing to continue the war, the Russian Provisional Government and Petrograd Soviet made efforts to humanise and democratise its command structure from its notoriously corrupt Tsarist hierarchy, to one that based the authority of officers on the support of their troops, and would no longer tolerate abuses of power. In particular, the Petrograd Soviet Order No. 1 suggested more equal treatment between soldiers and officers of all ranks, and electing representatives to the Petrograd Soviet, while still maintaining a hierarchical command structure and military disciple. Although some Tsarist officers had fled during the February Revolution, or suppressed mutinies by their subordinate soldiers, order was generally maintained.

The post-imperial Russian Army even conducted the Kerensky Offensive in July 1917, but it resulted in a defeat. This further weakened the military and fuelled distrust in the Alexander Kerensky-led Provisional Government, but the Bolshevik anti-Kerensky July Days protests in Petrograd as well as Polubotkivtsi uprising in Kiev (modern Kyiv) were successfully repressed. Kerensky's government and the Petrograd Soviet consolidated domestic political order by proclaiming the Russian Republic on 1 September 1917, thereby definitively abolishing the Russian Empire, as well as foiling the Kornilov affair. Meanwhile, the Central Rada was gaining influence in Ukraine, negotiating with the Russian Provisional Government for an autonomous Ukraine within Russia, demands which Kerensky's government partially but not yet fully recognised (e.g. he recognised the General Secretariat of Ukraine on 13 July 1917).

On 7 November 1917, during the October Revolution, Bolsheviks of the Petrograd Soviet took power in the Russian Republic, rapidly transforming controlled areas intro the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), and announcing that "Soviet Russia" would be withdrawing from war. In the meantime during the Kiev Bolshevik Uprising (8–13 November 1917, starting the Ukrainian–Soviet War), Central Rada and Bolshevik forces jointly expelled the Russian Provisional Government's Kiev Military District, and the Central Rada proclaimed the autonomous Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) on 20 November 1917, which would have supreme authority within Ukraine until order in the Russian Republic would be restored (which would never happen).

Talks between the new Bolshevik-led Soviet Russian government and the Central Powers started in Brest-Litovsk on 3 December 1917, and on the 17th a ceasefire went into effect. Peace talks soon followed, starting on 22 December.[4] As negotiations began, the Central Powers presented demands for the territory that they had occupied during the 1914–1916 period, including Poland, Lithuania and western Latvia. The Bolsheviks decided not to accept these terms and instead withdrew from the negotiations, eventually resulting in the breakdown of the ceasefire.[5] Leon Trotsky, head of the Soviet Russian delegation, hoped to delay talks until a revolution occurred within Germany, which would force them out of the war.[6]

Meanwhile on 17 December, the Kievan Bolsheviks demanded that the Central Rada of Ukraine recognise new Soviet government in Russia, but the Rada refused, and conflict erupted between them. The Bolsheviks fled from Kiev, regrouped in Kharkov (modern Kharkiv in eastern Ukraine) and established the Ukrainian People's Republic of Soviets there on 24 December 1917, subordinated to the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR, better known as "Soviet Russia"). The Rada tried to retake control quickly, but had to give up Kharkov (19 December 1917 – 10 January 1918).

In between on 25 December 1917, the Kiev-based Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) was invited to join the peace talks, and sent its representatives to Brest-Litovsk to negotiate for Ukrainian independence. On 10–12 January 1918, the Central Powers recognised the Ukrainian delegation at the talks in Brest as a separate and plenipotentiary to conduct negotiations on the behalf of Ukrainian People's Republic. On 22 January 1918, an overwhelming majority of the Central Rada voted in favour of Ukrainian independence, which was subsequently proclaimed in the Fourth Universal of the Ukrainian Central Council.

Trotsky was the leading advocate of the "neither war nor peace" policy, and on 28 January 1918 announced that Soviet Russia considered the war over.[7] This was unacceptable to the Germans, who were already transporting troops to the Western Front. While negotiations were ongoing, Soviet Commander-in-Chief Nikolai Krylenko oversaw the demobilization and democratization of the Russian Army, introducing elected commanders, ending all ranks, and sending troops home. On 29 January, Krylenko ordered demobilization of the whole army.[8] The same day, Bolshevik troops advancing on Kiev were defeated by the UPR in the Battle of Kruty, while the Bolshevik Kiev Arsenal January Uprising was repressed by UPR troops on 4 February. Nevertheless, the Bolsheviks conquered Kiev on 8 February 1918, forcing the Rada out of Ukraine's capital and to consider inviting the Central Powers to intervene. The German Chief of Staff, general Max Hoffmann, responded by signing the peace treaty with Ukrainian People's Republic on 9 February, and announced an end to the ceasefire with Soviet Russia in two-days time on 17 February, leading to the resumption of hostilities.[9] The German and Austro-Hungarian authorities were happy to accept the invitation of the desperate Central Rada to occupy Ukraine, and secure food supplies for their armies and populations, while protecting the UPR against the advancing Bolshevik forces of Soviet Russia.

Offensive

[edit]

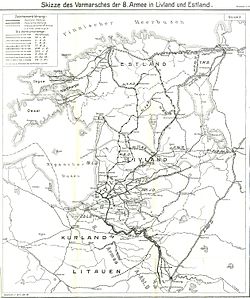

On 18 February, the German and Austro-Hungarian forces started a major three-pronged offensive against the Soviets with 53 divisions. The northern force advanced from Pskov towards Narva, the central force pushed towards Smolensk, and the southern force towards Kiev.[10]

The northern force, consisting of 16 divisions, captured the key Daugavpils junction on the first day.[2] This was soon followed by the capture of Pskov and securing Narva on 28 February.[9] The central forces of the 10th Army and XLI corps advanced towards Smolensk.[9] On 21 February Minsk was captured together with the headquarters of the Western Army Group.[2] The Southern forces broke through the remains of the Russian Southwestern Army Group, capturing Zhitomir (modern Zhytomyr) on 24 February. Kiev was secured on 2 March, one day after the Ukrainian Central Rada troops had arrived there.[2]

Central Powers armies had advanced over 150 miles (240 km) within a week, facing no serious Soviet resistance. German troops were now within 100 miles (160 km) of Petrograd, forcing the Soviets to transfer their capital to Moscow.[9] The rapid advance was described as a "Railway War" (der Eisenbahnfeldzug) with German soldiers using Russian railways to advance eastward.[11] General Hoffmann wrote in his diary on 22 February:

It is the most comical war I have ever known. We put a handful of infantrymen with machine guns and one gun onto a train and rush them off to the next station; they take it, make prisoners of the Bolsheviks, pick up few more troops, and so on. This proceeding has, at any rate, the charm of novelty.[2][12]

Political impact

[edit]As the German offensive was ongoing, Trotsky returned to Petrograd. Most of the leadership still preferred continuing the war, even though Russia was in no position to do so, due to the destruction of its army.[9] At this point Lenin intervened to push the Soviet leadership into acceptance of German terms, which by now had become even harsher. He was backed by other senior communists to include Kamenev, Zinoviev, and Stalin.[11]

After a stormy session of Lenin's ruling council, during which the revolution's leader went so far as to threaten resignation, he obtained a 116 to 85 vote in favour of the new German terms. The vote in the Central Committee was even closer, seven in favour and six against.[12] In the end, Trotsky switched his vote and German terms were accepted;[10] on 3 March, the Bolsheviks signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.[9]

On 24 February, one day before the arrival of German troops to Tallinn, the Estonian Salvation Committee declared the independence of Estonia. German occupation authorities refused to recognize the Estonian government and Germans were installed in positions of authority.[13]

Aftermath

[edit]

The Bolshevik capitulation on 3 March 1918 only ended the advance along a line from Narva to Northern Ukraine, as with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk the Soviet government gave up all rights to the southwestern region of the former Russian Empire. During the next few months, the southern Central Powers forces advanced over 500 miles further, capturing the whole of Ukraine and some territory beyond.[2]

German operations also continued in the Caucasus and Finland, where Germany assisted the White Finnish forces in the Finnish Civil War.[9] Under the treaty all Russian naval bases in the Baltic except Kronstadt were taken away, and the Russian Black Sea Fleet warships in Odesa were to be disarmed and detained. The Bolsheviks also agreed to the immediate return of 630,000 Austrian prisoners-of-war.[14]

With the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Soviet Russia had given up Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Belarus and Ukraine, enabling those territories to develop independently from Russian influence. Germany's intention was to turn these territories into political and territorial satellites, but this plan collapsed with Germany's own defeat within a year.[15] After the German surrender, the Soviets made an attempt to regain lost territories. They were successful in some areas like Ukraine, Belarus and the Caucasus, but were forced to recognize the independence of the Baltic States, Finland, and Poland.[16]

In Ukraine, Ukrainian troops took control of the Donets Basin in April 1918.[17] In the same month, Crimea was also cleared of the Bolsheviks by Ukrainian troops and the Imperial German Army.[18][19] On 13 March 1918 Ukrainian troops and the Austro-Hungarian Army had secured Odesa.[18] On 5 April 1918 the German army took control of Yekaterinoslav, and 3 days later Kharkov.[20] The German/Austro-Hungarian victories in Ukraine were due to the apathy of the locals and the inferior fighting skills of Bolsheviks troops compared to their Austro-Hungarian and German counterparts.[20]

In the Bolshevik government, Lenin consolidated his power; however, fearing the possibility of a renewed German threat along the Baltic, he moved the capital from Petrograd to Moscow on 12 March. Debates became far more restrained, and he was never again so strongly challenged as he was regarding the Brest-Litovsk treaty.[21]

See also

[edit]- 1918 Ukrainian coup d'état (29 April 1918)

- Ober Ost

- Finnish Civil War

- German Caucasus expedition

- Soviet westward offensive of 1918–1919

References

[edit]- ^ Gilbert 2023, p. 540.

- ^ a b c d e f Mawdsley 2007, p. 35.

- ^ "Lenin's speech at Extraordinary Seventh Congress of the RSDLP(B) 6th March 1918 about Political Report of the Central Committee". Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ Tucker & Roberts 2005, p. 662.

- ^ Mawdsley 2007, p. 31–32.

- ^ Tucker & Roberts 2005, pp. 662–663.

- ^ Mawdsley 2007, p. 32.

- ^ Mawdsley 2007, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tucker & Roberts 2005, p. 663.

- ^ a b Woodward 2009, p. 295.

- ^ a b Mawdsley 2007, p. 33.

- ^ a b Gilbert 2008, p. 399.

- ^ Parrott 2002, p. 145.

- ^ Gilbert 2008, p. 402.

- ^ Mawdsley 2007, p. 37.

- ^ Raffass 2012, p. 43.

- ^ "100 років тому визволили Бахмут і решту Донбасу" [100 years ago, Bakhmut and the rest of Donbas were liberated]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 18 April 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2024.

- ^ a b Tynchenko, Yaros (23 March 2018), "The Ukrainian Navy and the Crimean Issue in 1917-18", The Ukrainian Week, retrieved 14 October 2018

- ^ Germany Takes Control of Crimea, New York Herald (18 May 1918)

- ^ a b War Without Fronts: Atamans and Commissars in Ukraine, 1917-1919 by Mikhail Akulov, Harvard University, August 2013 (page 102 and 103)

- ^ Mawdsley 2007, p. 36–37.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gilbert, Martin (2008). The First World War: A Complete History. Phoenix. ISBN 9781409102793.

- Gilbert, Martin (2023). The First World War: A complete History. Moscow: Квадрига. ISBN 978-5-389-08465-0.

- Mawdsley, Evan (2007). The Russian Civil War. Pegasus Books. ISBN 9781933648156.

- Parrott, Andrew (2002). "The Baltic States from 1914 to 1923: The First World War and the Wars of Independence" (PDF). Baltic Defence Review. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- Raffass, Tania (2012). The Soviet Union - Federation or Empire?. Routledge. ISBN 9781136296437.

- Tucker, Spencer C.; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2005). World War I: A Student Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851098798.

- Woodward, David R. (2009). World War I Almanac. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438118963.