Saga of Erik the Red

The Saga of Erik the Red, in Old Norse: Eiríks saga rauða (ⓘ), is an Icelandic saga on the Norse exploration of North America. The original saga is thought to have been written in the 13th century. It is preserved in somewhat different versions in two manuscripts: Hauksbók (14th century) and Skálholtsbók (15th century).

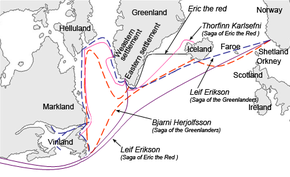

Despite its title, the saga mainly chronicles the life and expedition of Thorfinn Karlsefni and his wife Gudrid, also recounted in the Saga of the Greenlanders.[1] For this reason it was formerly also called Þorfinns saga karlsefnis;[2] Árni Magnússon wrote that title in the blank space at the top of the saga in Hauksbók.[3] It also details the events that led to the banishment of Erik the Red to Greenland and the preaching of Christianity by his son Leif Erikson as well as his discovery of Vinland after his longship was blown off course.

Synopsis

[edit]

Chapter 1

[edit]The Viking conqueror of Dublin, Olaf the White was married to Aud the Deep-Minded, who became a Christian. Following Olaf's death in battle, she and their son Thorstein the Red left Ireland for the Hebrides, where Thorstein became a great warrior king. Upon his death, she sailed to Orkney, where she married off Thorstein's daughter, Groa, and then to Iceland, where she had relatives and gave extensive land grants to those in her party.

Chapter 2

[edit]Erik the Red's thralls start a landslide that destroys a farm, leading to a feud that results in Erik's banishment first from the district and then from Iceland; he sails in search of land that had been reported to lie to the north, and explores and names Greenland, choosing an attractive name to encourage colonists. Where he settles becomes known as Eiriksfjord.

Chapter 3

[edit]Thorbjorn, a son of a well-born thrall who had accompanied Aud the Deep-Minded and been given land by her, has a daughter named Gudrid. One autumn, he proudly rejects a marriage proposal for her from Einar, a wealthy merchant who is also the son of a freedman. However, he is in financial difficulties; the following spring he announces he will leave Iceland and go to Greenland. The ship carrying his family and friends encounters bad weather and they reach Greenland only in autumn, after half have died of disease.

Chapter 4

[edit]Famine is raging in Greenland that winter; Thorkel, the prominent farmer with whom Thorbjorn's group is staying, asks a wandering seidworker called Thorbjorg the "little völva" to come to the winter feast and prophesy so that the people of the locality will know when conditions will improve. She asks for someone to sing varðlokkur (warding songs); Gudrid, although reluctant because she is Christian (her father has left while the heathen practice is going on), learned them from her foster mother and does so beautifully. Thorbjorg prophesies that the famine will soon end and that Gudrid will make two good marriages, one in Greenland and a second in Iceland, from which will come a great family. In the spring Thorbjorn sails to Brattahlid, where Erik the Red welcomes him and gives him land.

Chapter 5

[edit]This chapter introduces Erik the Red's sons, Leif and Thorstein. Leif sails to Norway but is blown off course to the Hebrides, where he conceives a son, Thorgils, by a well-born woman whom he declines to marry; when Thorgils is grown, his mother sends him to Greenland, where Leif recognizes him. In Norway, Leif becomes part of the court of King Olaf Tryggvason, who charges him with preaching Christianity when he returns to Greenland. On the return voyage, storms take him to an unknown land where he discovers wild wheat, vines, maple trees (and in one version of the saga, very large trees). Leif also rescues shipwrecked sailors, whom he looks after and converts to Christianity. Back in Greenland, he converts many people, including his mother, who builds a church, but not his father Erik, as a result of which Erik's wife leaves him. His brother Thorstein then organizes an expedition to explore the new country. In addition to both brothers, the group is to include their father, but Erik falls from his horse and is injured riding to the ship. (One of the two versions suggests he nonetheless goes.) The expedition is unsuccessful; after being blown in different directions by storms all summer, they return to Eiriksfjord in the fall.

Chapter 6

[edit]Thorstein marries Gudrid, but soon after dies in an epidemic at the farm where they are living with the joint owner, another Thorstein, and his wife Sigrid. Shortly before his death, Sigrid, who has died, rises as a draugr and tries to climb into bed with him. After his death, he himself reanimates and asks to speak to Gudrid; he tells her to end the Greenland Christian practise of burying people in unconsecrated ground and to bury him at the church, blames recent hauntings on the farm overseer, Gardi, whose body he says should be burned, and predicts a great future for her but warns her not to marry another Greenlander and asks her to give their money to the church. He then died soon after in his old cottage house made of human remains.

Chapter 7

[edit]Thorfinn Karlsefni, a wealthy Icelandic merchant, visits Greenland as part of a trading party in two ships. They spend the winter at Brattahlid and assist Erik the Red in providing a magnificent Yule feast; Karlsefni then asks to marry Gudrid, and the feast is extended as a wedding feast.

Chapter 8

[edit]A group of 160 people in two ships, including Karlsefni and other Icelanders but mostly Greenlanders, set out to find the land to the west, now dubbed Vinland. The wind carries them to a place they call Helluland, where there are large slabs of stone and many foxes, then south to a wooded area they call Markland and a promontory they call Kjalarness. They put in at a bay and have two fast-running Scottish thralls, gifts from King Olaf to Leif Erikson, scout the land and they bring back grapes and wheat. They overwinter inland from a fjord that they call Straumfjord, in mountainous country with tall grass; an island at the mouth of the fjord is full of nesting birds. Despite having brought grazing animals, they are unprepared for the harshness of winter there, and run short of food. Thorhall the Hunter, a pagan friend and servant of Erik's, then disappears and they find him after three days lying on a cliff-top, mumbling and pinching himself. Soon a strange kind of whale washes up on-shore; the meat sickens them all, and then Thorhall claims credit for it as an answer to his making a poem for Thor, whom he calls his fulltrúi (patron deity). So they throw the rest over the cliff and pray to God; the weather then clears and they have good fishing and enough food.

Chapter 9

[edit]In spring, most of the expedition decide to go south in search of Vinland. Thorhall wants to go north and is joined on one ship by nine others, but the wind drives the ship east across the Atlantic to Ireland, where they are beaten and made slaves and Thorhall dies.

Chapter 10

[edit]The larger expedition, led by Karlsefni, discovers a place they call Hop ("tidal river"), where a river flows through a lake to the sea; the country is rich in wildlife, fishing is excellent, wheat and grapes grow plentifully, and it does not snow that winter. They have a first encounter with natives they call Skrælings, who use boats covered in animal skins and wave sticks in the air that make a threshing sound; the Norsemen display a white shield as a sign of peace.

Chapter 11

[edit]The Skrælings return in a larger group and the Norse trade red cloth for animal pelts (refusing to also trade swords and spears) until the Skrælings take fright and leave at the sight of a bull that has got loose. Three weeks later they return in still larger numbers, whirling the sticks counterclockwise rather than clockwise and howling. Battle is joined, and the Skrælings use something like a ballista to hurl a large, heavy sphere over the Norsemen's heads, causing them to retreat. Freydis, an illegitimate daughter of Erik the Red, then emerges from her hut, heavily pregnant, and pursues them, berating them as cowards; when the Skrælings surround her, she pulls a sword from a dead man's hand, bares one breast, and slaps the sword against it, which frightens the Skrælings into leaving. The group realize that some of the attacking force were an illusion. Having lost two of their number, they decide the place is not safe and sail back north to Straumfjord, on the way encountering five sleeping men with containers of deer marrow and blood, whom they kill on the assumption they are outlaws. Karlsefni then takes one ship north in search of Thorhall, finding a desolate forested area where they lay up on the bank of a river that flows westward to the sea.

Chapter 12

[edit]Thorvald, traveling with Karlsefni, is killed by a uniped that shoots him in the groin with a bow and arrow. Karlsefni buries him in Vinland, in the area of what is present day Nova Scotia, Canada. The ship returns to Straumfjord, but amid increasing dissension they decide to return home. Karlsefni's son Snorri, born in the new land, is three years old when they leave. In Markland, they encounter five Skrælings; the three adults sink into the ground and escape, but they capture the two boys and baptize them; they learn from them that the Skrælings are cave-dwellers ruled by two kings named Avaldamon and Avaldidida, and that a nearby country is inhabited by people who go about in white, carrying poles with cloth attached, and shouting; the saga writer says that this was thought to be the legendary Hvítramannaland, and one version adds that that was also called Great Ireland. They sail back to Greenland and overwinter with Erik the Red.

Chapter 13

[edit]The ship with the rest of the expedition, under another Icelander, Bjarni Grimolfsson, is blown off-course into either the Greenland Sea or the sea west of Ireland, depending on the saga version, where it is attacked by marine worms and starts to sink. The ship's boat is resistant, having been treated with tar made of seal blubber, but can carry only half those aboard. At Bjarni's suggestion, they draw lots, but on request he gives up his seat in the boat to a young Icelander. Bjarni and the rest left on the ship drown; those in the boat reach land.

Chapter 14

[edit]After a year and a half in Greenland, Karlsefni and Gudrid return to Iceland, where they have a second son; their grandchildren become the parents of three bishops.

Analysis

[edit]The two versions of the Saga of Erik the Red, in the 14th-century Hauksbók (and 17th-century paper copies) and the 15th-century Skálholtsbók, appear to derive from a common original written in the 13th century[2][4] but vary considerably in details. Haukr Erlendsson and his assistants are thought to have revised the text, making it less colloquial and more stylish, while the Skálholtsbók version appears to be a faithful but somewhat careless copy of the original.[5] Although classified as one of the Sagas of Icelanders, it is closer in subject matter to medieval travel narratives than to either the sagas about families and regions of Iceland or those that are biographies of one person, and also unusual in its focus on a woman, Gudrid.[6]

The saga has numerous parallels to the Saga of the Greenlanders, including recurring characters and accounts of the same expeditions and events, but differs in describing two base camps, at Straumfjord and Hop, whereas in the Saga of the Greenlanders Thorfinn Karlsefni and those with him settle in a place that is referred to simply as Vinland. Conversely, the Saga of Eric the Red describes only one expedition, led by Karlsefni, and has combined into it those Erik's son Thorvald and daughter Freydis, which are recounted in the Saga of the Greenlanders. It also has a very different account of the original discovery of Vinland; in the Saga of Eric the Red, Leif Erikson discovers it accidentally when he is blown off course on the way back to Greenland from Norway, while in the Saga of the Greenlanders, Bjarni Herjolfsson had accidentally sighted land to the west approximately fifteen years before Leif organized an exploratory voyage. This last is thought to stem from the saga having been written to incorporate a story that Leif evangelized in Greenland on behalf of Olaf Tryggvason, which appears to have been invented by the monk Gunnlaug Leifsson in his now lost Latin life of King Olaf (c. 1200), in order to add another country to the list of those converted to Christianity by the king; as a result of incorporating this episode, the Saga of Erik the Red often associates the same events, such as Erik's fall from his horse, with different voyages than the Saga of the Greenlanders, which apparently predates Gunnlaug's work.[7]

The Saga of Erik the Red contains an unusual amount of pagan practise, sorcery, and ghost stories. It has been used as a source on Old Norse religion and belief, in particular on the practice of prophecy as described in the scene with Thorbjorg, but is often described as unreliable.[8] One scholar has described it as "a polemical attack on the pagan practices still supposedly prevalent around the year 1000 in Greenland".[9]

Translations into English

[edit]There have been numerous translations of the saga, some of the most prominent of which are:

- Jones, Gwyn (trans.), "Eirik the Red's Saga", in The Norse Atlantic Saga: Being the Norse Voyages of Discovery and Settlement to Iceland, Greenland, and North America, new ed (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), pp. 207–35. Based on Skálholtsbók, showing some variants from Hauksbók.

- Kunz, Keneva (trans.), "Erik the Red's Saga", in The Sagas of Icelanders: A Selection (London: Penguin, 2001), pp. 653–74. Apparently translates the Skálholtsbók text.

- Magnusson, Magnus; Hermann Pálsson (trans.), 'Eirik's Saga', in The Vinland Sagas (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1965), pp. 73–105. Based on Skálholtsbók, though readings from Hauksbók are occasionally preferred.

- Reeves, Arthur Middleton (ed. and trans.), The Saga of Eric the Red, also Called the Saga of Thorfinn Karlsefni and Snorri Thorbrandsson, in The Finding of Wineland the Good: The History of the Icelandic Discovery of America (London: Henry Frowde, 1890), pp. 28–52, available online at Archive.org. Based on the Hauksbók text (which Reeves refers to in the apparatus as ÞsK), though the text does draw some readings from Skálholtsbók (which Reeves refers to as EsR). Variants are thoroughly listed. Editions and facsimiles of both manuscripts also included (Hauksbók pp. 104–21, Skálholtsbók pp. 122–39).

- Sephton, J. (trans.), Eirik the Red's Saga: A Translation Read before the Literary and Philosophical Society of Liverpool, January 12, 1880 (Liverpool: Marples, 1880), available online at Gutenberg.org (closer to the printed version) and Icelandic Saga Database. Passages in square brackets are based on Hauksbók; other passages are based on Skálholtsbók, but with some readings from Hauksbók.

- Saga of Erik the Red, public domain audiobook at Librivox.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Oleson, T.J. (1979) [1966]. "Thorfinnr Karlsefni Thordarson". In Brown, George Williams (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. I (1000–1700) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ a b Halldór Hermannsson, "Eiríks saga rauða or Þorfinns saga karlsefnis ok Snorra Þorbrandssonar", Bibliography of the Icelandic Sagas and Minor Tales, Islandica 1, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Libraries, 1908, OCLC 604126691, p. 16.

- ^ Her hefr upp sǫgu þeirra Þorfinnz Karlsefnis oc Snorra Þorbrandzsonar, "Here begins the saga of Thorfinn Karlsefni and Snorri Thorbrandsson"; Arthur Middleton Reeves, (ed. and trans.), The Saga of Eric the Red, also Called the Saga of Thorfinn Karlsefni and Snorri Thorbrandsson, The Finding of Wineland the Good: The History of the Icelandic Discovery of America, London: Henry Frowde, 1890, OCLC 461045740, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Børge Nordbø, "Eirik Raudes saga", Store norske leksikon, retrieved December 1, 2019. (in Norwegian)

- ^ Magnus Magnusson and Hermann Pálsson, "Introduction", The Vinland Sagas: The Norse Discovery of America, Penguin Classics, Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1965, ISBN 0140441549, pp. 30–31, citing Sven B.F. Jansson, Sagorna om Vinland, Volume 1, 1944.

- ^ Sverrir Tómasson, "Old Icelandic Prose", in: Daisy Neijmann, ed., A History of Icelandic Literature, Histories of Scandinavian Literature 5, The American-Scandinavian Foundation, Lincoln, Nebraska / London: University of Nebraska Press, 2006, ISBN 9780803233461, pp. 127, 135.

- ^ Magnusson and Pálsson, "Introduction", pp. 32–35, citing Jón Jóhannesson, "Aldur Grænlendinga Sögu", Nordœla, 1956, pp. 149–58.

- ^ For example by John Lindow, Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs, [2001], Oxford / New York: Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0195153820, p. 265 on the seid ceremony; by Jan de Vries, Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte, Volume 1, Grundriss der germanischen Philologie 12.I, rev. ed. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1956, 3rd ed. 1970, p. 221 on the varðlokkur, Volume 2, Grundriss der germanischen Philologie 12.II, rev. ed. Berlin: de Gruyter, 1957, 3rd ed. 1970, p. 354 skeptically on Thorhall and his relationship with Thor (in German).

- ^ Clive Tolley, Shamanism in Norse Myth and Magic, 2 vols., Folklore Fellows Communications 296–97, Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2009, ISBN 9789514110306, p. 488.

External links

[edit]- Saga of Erik the Red, English translation at the Icelandic Saga Database

- Eiríks saga rauða The saga with standardized Old Norse spelling at heimskringla.no

- Arthur Middleton Reeves, North Ludlow Beamish, and Rasmus B. Anderson, The Norse Discovery of America (1906)

- The saga with standardized modern Icelandic spelling

- A treatment of the nationality of Leifr Eiríksson

Eirik the Red's Saga public domain audiobook at LibriVox (Sephton Translation)

Eirik the Red's Saga public domain audiobook at LibriVox (Sephton Translation) Saga of Erik the Red public domain audiobook at LibriVox (Reeves Translation)

Saga of Erik the Red public domain audiobook at LibriVox (Reeves Translation)