Science and technology in Tanzania

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Science and technology in Tanzania describes developments and trends in higher education, science, technology, innovation policy, and governance in the United Republic of Tanzania since the turn of the century.

Socio-economic context

[edit]

Tanzania has been a multiparty parliamentary democracy since the early 1990s. In common with much of Africa, growing indebtedness and falling commodity prices forced the country to adopt a series of structural adjustment programmes proposed by the International Monetary Fund between 1986 and the early 2000s. Over this period, the country’s poor economic performance prompted a progressive abandonment of neoliberalism. Economic indicators subsequently picked up, with growth averaging 6.0–7.8% per year between 2001 and 2014. Though still high, donor funding dropped substantially between 2007 and 2012. As the economy becomes less reliant on donor funding, it may gradually diversify.[1]

Impressive growth since 2001 had not significantly altered the country’s economic structure by 2015. Agriculture accounted for 34% of GDP in 2013, compared to 7% for manufacturing. GDP per capita remains low by the standards of other members of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) but nevertheless progressed between 2009 and 2013. Tanzania is also a member of the East African Community (EAC) with which its trade more than doubled between 2008 and 2012.[1][2] The African continent plans to create an African Economic Community by 2028, which would be built on the main regional economic communities, including the EAC and SADC.

Tanzania graduated to lower middle-income status in 2019. The National Development Plan 2016–2021 (2016) emphasizes industrialization and human development as twin priorities. The plan uses the phrase ‘business unusual’ to encapsulate its ambition of graduating to a middle-income, semi-industrial economy by 2025, a goal first set out in the Tanzania Development Vision to 2025 (1999).[3]

As of early 2021, several major infrastructure projects are being implemented that have implications for science, technology and innovation. In April 2017, construction got underway of the Tanzania Standard Gauge Railway system, which will extend into Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This railway replaces an old metre-gauge system and is expected to reduce freight costs by 40%. As of June 2020, the first phase (300 km) was about 80% complete; the remaining four phases are set to add an additional 1 450 km.[3][4]

Status of national innovation system

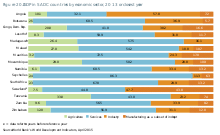

[edit]Status of national innovation systems in the Southern Africa Development Community in 2015, in terms of their potential to survive, grow and evolve

| Category | Country | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Fragile | Democratic Republic of Congo, Lesotho, Madagascar, Swaziland, Zimbabwe | Fragile systems tend to be characterized by political instability, be it from external threats or internal political schisms. |

| Viable | Angola, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, Tanzania, Zambia | Viable systems encompass thriving systems but also faltering ones, albeit in a context of political stability. |

| Evolving | Botswana, Mauritius, South Africa | In evolving systems, countries are mutating through the effects of policy and their mutation may also affect the emerging regional system of innovation. |

Source of table: Mbula-Kraemer, Erika and Scerri, Mario (2015) Southern Africa. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030. UNESCO, Paris, Table 20.5.

Higher education

[edit]

In 2010, Tanzania devoted 1.7% of GDP to higher education and 6.2% of GDP to education as a whole, one of the highest rates in Africa.

Even though Tanzania had eight public institutions of higher education and a plethora of private institutions in 2015, fewer than half of secondary school-leavers who qualify for entry obtain a place at university. The establishment of the Nelson Mandela African Institute of Science and Technology in Arusha in 2011 should augment Tanzania’s academic capacity considerably. This university has been designed as a research-intensive institution with postgraduate programmes in science, engineering and technology. Life sciences and bio-engineering are some of the initial niche areas, taking advantage of the immense biodiversity in the region. Together with its sister institution set up in Abuja (Nigeria) in 2007, it forms the vanguard of a planned pan-African network of such institutes.[1]

A needed assessment in 2011 concluded that 'there must be a coordinated effort between the education and employment sectors to ensure that the education system is producing not only qualified graduates, but those whose knowledge and skills are both in demand and which will meet the development needs of the country. Unfortunately, issues of student performance, quality of teaching and students’ lack of readiness for jobs in science and technology are widespread in Tanzania'. The study also revealed that data gathered during the study 'show a lack of human and material resources throughout mainland Tanzania and Zanzibar. The needs appear to be more dire in rural versus urban areas, however, only marginally so'.[5]

A 2011 review of higher education in Tanzania found a certain indifference to research and resistance to

change in the institutional culture of universities. These showed an administrative bias, despite policy instruments being in place to develop and finance the traditional tasks of higher education, training, research and extension. 'The weak recognition of research and extension produces discrimination or lack of incentives for active researchers', observed the study. It also found that the insufficient quality and relevance of the research undertaken discouraged policy-makers and private sector from using local research outputs and prompted them to seek research findings from abroad. The study also pinpointed 'the lack of institutional and national mechanisms for assessing research performance' and the 'limited efforts in attracting the private sector, individuals, business people, trade unions and community organizations into contributing significantly to the national science, technology and innovation effort by way of funding or shared sponsorship of research programmes'.[6]

After its Innovation and Entrepreneurship Centre opened in 2015, the University of Dar es Salaam incorporated practice-oriented innovation and entrepreneurship courses into its curricula, as undergraduate and postgraduate electives. The Centre offers business counselling and incubation services to students, staff and SMEs, including business plan development, advertising and marketing and financial guidance.[3]

Research trends

[edit]Financial investment in research

[edit]In 2010, the United Republic of Tanzania devoted 0.38% of GDP to research and development. This was equivalent to $7.7 per capita (in current purchasing power parity dollars) and $110,000 per researcher (head counts) in current purchasing power parity dollars). The breakdown of research spending was as follows: government (57.5%), business (0.1%), higher education (0.3%), private non-profit (0.1%) and foreign sources (42.0%).[1] Tanzania was ranked 90th in the Global Innovation Index in 2021, up from 97th in 2019.[7][8][9][10][11]

By 2013, the most recent year with data as of 2021 according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, the United Republic of Tanzania devoted 0.51% of GDP to research and development.

Human investment in research

[edit]There were just 69 researchers (head count) per million population in 2010. This was similar to the researcher density in Mali and Mozambique (66), Angola (73) and Burkina Faso (74) but much lower than the research density in the other SADC countries of Namibia (343), Botswana (344) and, above all, South Africa (818).[1]

One in four researchers was a woman in Tanzania in 2010 (25.4%).[1] A 2011 assessment of women scientists’ participation in science, engineering and technological industries found that patriarchy and male dominance continued to influence gender inequalities in Tanzanian society and that this, in turn, had a negative impact on the levels of participation of women scientists even within industries based on science and engineering.[12]

Scientific output

[edit]In 2014, Tanzania counted 15 publications per million inhabitants in internationally catalogued journals, according to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded). This placed Tanzania tenth out of the 15 SADC countries, well behind Namibia (59), Mauritius (71), Botswana (103) and, above all, South Africa (175). The average for sub-Saharan Africa was 20 scientific publications per million inhabitants, compared to a global average of 176. Two-thirds of the publications produced by SADC countries had at least one foreign co-author. Between 2008 and 2014, Tanzania's main scientific partners were the USA and the UK, followed by Kenya, Switzerland and South Africa.[1]

In 2019, Tanzania produced 30 publications per million inhabitants. Its main scientific partners over the 2017–2019 period were the USA and UK, followed by South Africa, Kenya and Germany.[3]

Science policy

[edit]Institutional context

[edit]The main body in charge of science, technology and innovation policy in Tanzania is the Ministry of Communication, Science and Technology and its main co-ordination agency, the Commission for Science and Technology (COSTECH). COSTECH co-ordinates a number of research institutes engaged with industry, health care, agriculture, natural resources, energy and the environment.[1]

A 2011 survey found that the public policy making process was inadequately informed by research-based evidence in Tanzania, largely due to the limited interface between researchers and public policy-makers in the government. Among the challenges threatening the research-policy linkage, the study cited:[13]

- the poor quality of research findings capable of informing policy;

- political interference and the lack of a National Research Reference Bureau;

- lack of good governance;

- the preference for supply-driven research, rather than demand-driven research, leading to much of research being shelved;

- the ratification of too many international conventions with little prior analysis of their relevance to Tanzania and;

- an overdependence on donors.

Reform of national science policy

[edit]The reform of Tanzania’s national innovation system got under way on 15 December 2008 with the first consultation of stakeholders at a workshop in Bagamoyo (Tanzania). The reform was implemented under the umbrella of the One UN programme, which had been launched the previous year, inspired by a report by a high-level task force proposing that the United Nations focus on Delivering as One. Within the One UN programme, several United Nations agencies worked together to formulate joint programmes for each of the eight pilot countries, with funding originating mainly from the One UN Fund. Tanzania was one of these eight pilot countries. (The One UN programme has since become the United Nations Development Assistance Programme.)

UNESCO’s participation in the One UN Programme for Tanzania came in response to the request made by the President, His Excellency Jakaya Mrisho Kikwete, for UNESCO’s assistance in conducting a comprehensive review of Tanzania's first National Science and Technology Policy (1996), in a June 2007 letter to UNESCO’s Director-General. In August 2007, the heads of UN agencies agreed to UNESCO’s proposal for science components to be included in the One UN programme for Tanzania, in support of the government’s Vision 2025 (1998) objective of ‘transform[ing] the economy into a strong, resilient and competitive one, buttressed by science and technology’. Peter Msolla, Tanzanian Minister of Communications, Science and Technology, told fellow ministers attending the High-level Segment of the meeting of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission on 1 July 2008 that, ‘without a dose of innovation [in Tanzania], the macro-economic gains achieved over the years through the implementation of sound economic policies would be wiped out.’

Under the umbrella of the One UN Initiative, UNESCO and government departments and agencies formulated a series of proposals for a total reform budget of US$10 million, to be financed from the One UN fund and other sources. UNESCO began by providing support for the mainstreaming of science, technology and innovation into the new National Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy for the mainland and Zanzibar namely, Mkukuta II and Mkuza II, including in the field of tourism.

The revised science policy was published in 2010. Entitled National Research and Development Policy, it recognizes the need to improve the process of prioritization of research capacities, international co-operation in strategic areas of research and development and planning for human resources; it also makes provisions for the establishment of a National Research Fund. This policy was, in turn, reviewed in 2012 and 2013.[1]

In 2011, Tanzania signed a bilateral agreement with South Africa for scientific cooperation in the following areas: intellectual property; science, technology and innovation policy; biotechnology; information and communication technologies; and nanotechnology and materials science.[1]

The National Research and Development Policy was due to be updated in 2020 to incorporate innovation, industrialization and technology transfer but the 2021 edition of the UNESCO Science Report did not find evidence of the policy having materialized.[3]

Biotechnology policy

[edit]Tanzania published a policy on biotechnology in December 2010. This field faces a number of challenges in Tanzania. For instance:[1][14]

- although the first academic degree courses in biotechnology and industrial microbiology were introduced at Sokoine University of Agriculture in 2004 and at the University of Dar es Salaam in 2005, Tanzania still lacks a critical mass of researchers with skills in biotech-related fields like bioinformatics. Even when scientists have been sent abroad for critical training, poor infrastructure prevents them from putting their newly gained knowledge into practice upon their return.

- Problems encountered in diagnostics and vaccination stem from the reliance upon biologicals produced elsewhere. Biosafety regulations dating from 2005 prevent confined field trials with genetically modified organisms.

- Incentives are lacking for academics to collaborate with the private sector. Obtaining a patent or developing a product does not affect an academic’s remuneration and researchers are evaluated solely on the basis of their academic credentials and publications.

- The current lack of university–industry collaboration leaves academic research disconnected from market needs and private funding. The University of Dar Es Salaam has made an effort to expose students to the business world by creating a Business Centre and setting up the Tanzania Gatsby Foundation’s project to fund student research proposals of relevance to small and medium-sized enterprises. However, both of these schemes are of limited geographical scope and uncertain sustainability.

- Most research in Tanzania is largely donor-funded via bilateral agreements, with donor funds varying from 52% to 70% of the total. Research has benefited greatly from these funds but it does mean that research topics are preselected by donors.

- The conditions for export and business incubation have improved in recent years, thanks to the adoption of an export policy and a Programme for Business Environment Strengthening for Tanzania in 2009. However, no specific fiscal incentives have been envisioned to promote business in the biotechnology sector, resource limitations being given as the principal cause. Private entrepreneurs have appealed for tax regimes to support ideas developed domestically and for the provision of loans and incubation structures to allow them to compete against foreign products.

- Communication and co-ordination between the relevant ministries may also need optimizing, in order to provide the necessary resources for policy implementation. For example, in 2011, lack of co-ordination between COSTECH, the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare and the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Marketing appeared to be hindering potential implementation and exploitation of patent exemptions related to the agreement on Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights.

Information and communication technologies

[edit]Tanzania's National ICT Policy (2016) updates the government’s 2003 strategy. It aims to strengthen leadership and cultivate human capital in this field, while expanding the provision of reliable broadband.[3]

As of early 2021, there are plans to establish an accreditation body for ICT professionals and a separate mechanism connecting training institutions to employers. A new programme will empower citizens to use ICTs. Benchmarks include raising expenditure on ICTs to 0.3% of GDP and filling 90% of the National Data Centre’s capacity by mid-2021.[3]

The National Data Centre was established in 2016. In addition to offering public and private entities services such as data storage and back-up and domain registration, the Centre has ventured into fintech; in July 2020, it launched the N-Card enabling digital payments.[3]

Mobile financial services are beginning to substitute conventional banking and payment channels. By 2019, 78% of adults in rural Tanzania could reach formal financial services within a radius of 5 km. As these services have expanded, dependence on informal financial services has declined: from 16% to 7% over 2014–2017.[3][15]

Participation in international scientific networks

[edit]Tanzania is a member of several scientific networks in Africa, including the African Biosafety Network of Expertise.

The Biosciences Eastern and Central Africa Network (BecA) is one of four sub-regional research hubs established by NEPAD. It manages the African Biosciences Challenge Fund, which was established in 2010. Tanzanian scientists and graduate students from universities and national agricultural research organizations are entitled to apply to this fund for fellowships and to attend training workshops at BecA.

Since 2014, Tanzania has hosted one of the African Institutes for Mathematical Sciences.

Tanzania is a member of the African Regional Intellectual Property Organisation.

Tanzania is one of the signatories of the Gaborone Declaration for Sustainability in Africa (2012).

Global Health Security Agenda

[edit]The Ebola epidemic in 2014 highlighted the challenge of mobilizing funds, equipment and human resources to manage a rapidly evolving health crisis. In 2015, the United States of America decided to invest US$1 billion over the next five years in preventing, detecting and responding to future infectious disease outbreaks in 17 countries, within its Global Health Security Agenda. Tanzania is one of these 17 countries. The others are: (in Africa) Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania and Uganda; (in Asia): Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Viet Nam.

Regional policy framework for science and technology

[edit]The United Republic of Tanzania is not one of four SADC countries which had ratified the SADC Protocol on Science, Technology and Innovation (2008) by 2015. Ten of the 15 SADC countries must ratify the protocol for it to enter into force but, by 2015, only Botswana, Mauritius, Mozambique and South Africa had done so. The protocol promotes legal and political co-operation. It stresses the importance of science and technology for achieving 'sustainable and equitable socio-economic growth and poverty eradication'.

Two primary policy documents operationalize the SADC Treaty (1992), the Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan for 2005–2020, adopted in 2003, and the Strategic Indicative Plan for the Organ (2004). The Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan for 2005–2020 identifies the region’s 12 priority areas for both sectorial and cross-cutting intervention, mapping out goals and setting up concrete targets for each. The four sectorial areas are: trade and economic liberalization, infrastructure, sustainable food security and human and social development. The eight cross-cutting areas are:

- poverty;

- combating the HIV/AIDS pandemic;

- gender equality;

- science and technology;

- information and communication technologies (ICTs);

- environment and sustainable development;

- private sector development; and

- statistics.

Targets include:

- ensuring that 50% of decision-making positions in the public sector are held by women by 2015;

- raising gross domestic expenditure on research and development (GERD) to at least 1% of GDP by 2015;

- increasing intra-regional trade to at least 35% of total SADC trade by 2008 (10% in 2008);

- increasing the share of manufacturing to 25% of GDP by 2015; and

- achieving100% connectivity to the regional power grid for all member states by 2012.

A 2013 mid-term review of the Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan for 2005–2020 noted that limited progress had been made towards STI targets, owing to the lack of human and financial resources at the SADC Secretariat to co-ordinate STI programmes. Meeting in Maputo, Mozambique, in June 2014, SADC ministers of science, technology and innovation, education and training adopted the SADC Regional Strategic Plan on Science, Technology and Innovation for 2015–2020 to guide implementation of regional programmes.

Concerning sustainable development, in 1999, the SADC adopted a protocol governing wildlife, forestry, shared water courses and the environment, including climate change, the SADC Protocol on Wildlife Conservation and Law Enforcement (1999). More recently, SADC has initiated a number of regional and national initiatives to mitigate the impact of climate change. In 2013, ministers responsible for the environment and natural resources approved the development of the SADC Regional Climate Change programme. In addition, COMESA, the East African Community and SADC have implemented a joint five-year initiative since 2010 known as the Tripartite Programme on Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation, or The African Solution to Address Climate Change.

See also

[edit]- Science and technology in Botswana

- Science and technology in Cabo Verde

- Science and technology in Côte d'Ivoire

- Science and technology in Malawi

- Science and technology in Uganda

- Science and technology in Zimbabwe

Sources

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0. Text taken from UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030, 535-565, UNESCO, UNESCO Publishing.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0. Text taken from UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030, 535-565, UNESCO, UNESCO Publishing.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kraemer-Mbula, Erika; Scerri, Mario (2015). Southern Africa. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. pp. 535–565. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- ^ African Economic Outlook. African Development Bank, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and United Nations Development Programme. 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kraemer-Mbula, Erika; Sheikheldin, Gussai; Karimanzira, Rungano (2021). Southern Africa. In: UNESCO Science Report: the Race Against Time for Smarter Development. UNESCO Publishing. pp. 534–573. ISBN 978-92-3-100450-6.

- ^ "Tanzania SGR project timeline and all you need to know". Construction Review Online. 2020-07-24. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ^ Hamilton, Mark; et al. (2011). Needs Assessment Study of Tanzania's Science Education (PDF). Dar es Salaam: UNESCO study commissioned of Economic and Social Research Foundation.

- ^ Aguirre Bastos, Carlos; Rebois, Roland R. (2011). Review and Evaluation of the Performance of Tanzania's Higher Education Institutions in Science, Technology and Innovation (PDF). Dar es Salaam: UNESCO.

- ^ "Global Innovation Index 2021". World Intellectual Property Organization. United Nations. Retrieved 2022-03-05.

- ^ "Release of the Global Innovation Index 2020: Who Will Finance Innovation?". www.wipo.int. Retrieved 2021-09-02.

- ^ "Global Innovation Index 2019". www.wipo.int. Retrieved 2021-09-02.

- ^ "RTD - Item". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2021-09-02.

- ^ "Global Innovation Index". INSEAD Knowledge. 2013-10-28. Retrieved 2021-09-02.

- ^ Kasembe, Margaret K.; Mashauri, Specioza (2011). Assessment of Women Scientists' Participation in Science, Engineering and Technological Industries in Tanzania (PDF). UNESCO.

- ^ Research-Policy Linkages of Science-Related Ministries and their Research Organizations (PDF). Dar es Salaam: UNESCO study commissioned of Economic and Social Research Foundation. 2011.

- ^ Pahlavan, G. (2011). Biotechnology and Bioentrepreneurship in Tanzania (PDF). Dar es Salaam: UNESCO.

- ^ United Republic of Tanzania (2019). Voluntary National Review: Empowering People and Ensuring Inclusiveness and Equality (PDF). United Republic of Tanzania.

.