Li Sao

Two pages from "Li Sao" from a 1645 illustrated copy of the Songs of Chu, showing the poem "The Lament", with its name being enhanced by the addition of the character 經 (jing), which is usually only so used in the case of referring to one of the Chinese classics. | |

| Author | (trad.) Qu Yuan |

|---|---|

| Published | c. 3rd century BCE |

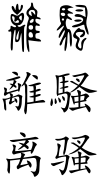

| Li Sao | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Li Sao" in seal script (top), Traditional (middle), and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 離騷 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 离骚 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Encountering Sorrow" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"Li Sao" (Chinese: 離騷; pinyin: Lí Sāo; translation: "Encountering Sorrow") is an ancient Chinese poem from the anthology Chuci traditionally attributed to Qu Yuan. Li Sao dates from the 3rd century BCE, during the Chinese Warring States period.

Background

[edit]The poem "Li Sao" is in the Chuci collection and is traditionally attributed to Qu Yuan[a] of the Kingdom of Chu, who died about 278 BCE.

Qu Yuan manifests himself in a poetic character, in the tradition of Classical Chinese poetry, contrasting with the anonymous poetic voices encountered in the Shijing and the other early poems which exist as preserved in the form of incidental incorporations into various documents of ancient miscellany. The rest of the Chuci anthology is centered on the "Li Sao", the purported biography of its author Qu Yuan.

In "Li Sao", the poet despairs that he has been plotted against by evil factions at court with his resulting rejection by his lord and then recounts a series of shamanistic spirit journeys to various mythological realms, engaging or attempting to engage with a variety of divine or spiritual beings, with the theme of the righteous minister unfairly rejected sometimes becoming exaggerated in the long history of later literary criticism and allegorical interpretation. It dates from the time of King Huai of Chu, in the third century BCE.

Meaning of title

[edit]The meaning of the title "Li Sao" is not straightforward. In the biography of Qu Yuan, li sao is explained as being as equivalent to li you 'leaving with sorrow' (Sima Qian, Shiji or the Records of the Grand Historian). Inference must be made that 'meeting with sorrow' must have been meant.[1]

However, the 1st century CE scholar Ban Gu explicitly glossed the title as "encountering sorrow".[2][3]

Content

[edit]The Li Sao begins with the poet's introduction of himself, his ancestry, and his former shamanic glory.

Of the god-king Gao-yang I am the far offspring, | 帝高陽之苗裔兮, |

| —Li Sao, stanzas 1 to 3 (Stephen Owen, trans.)[4] |

He references his current situation, and then recounts his fantastical physical and spiritual trip across the landscapes of ancient China, real and mythological. "Li Sao" is a seminal work in the large Chinese tradition of landscape and travel literature.[5]

I knelt with robes open, thus stated my case, | 跪敷衽以陳辭兮, |

| —Li Sao, stanzas 46–49 (Owen, trans.)[6] |

"Li Sao" is also a political allegory in which the poet laments that his own righteousness, purity, and honor are unappreciated and go unused in a corrupt world. The poet alludes to being slandered by enemies and being rejected by the king he served (King Huai of Chu).

Those men of faction had ill-gotten pleasures, | 惟黨人之偷樂兮, |

| —Li Sao, stanzas 9 to 11 (Owen, trans.)[7] |

As a representative work of Chu poetry it makes use of a wide range of metaphors derived from the culture of Chu, which was strongly associated with a Chinese form of shamanism, and the poet spends much of "Li Sao" on a spirit journey visiting with spirits and deities. The poem's main themes include Qu Yuan's falling victim to intrigues in the court of Chu, and subsequent exile; his desire to remain pure and untainted by the corruption that was rife in the court; and also his lamentation at the gradual decline of the once-powerful state of Chu.

The poet decides to leave and join Peng Xian (Chinese: 彭咸), a figure that many believe to be the God of Sun. Wang Yi, the Han dynasty commentator to the Chuci, believed Peng Xian to have been a Shang dynasty official who, legend says, drowned himself after his wise advice was rejected by the king (but this legend may have been of later make, influenced by the circumstances of Qu Yuan drowning himself).[8] Peng Xian may also have been an ancient shaman who later came to symbolize hermit seclusion.[9]

It is now done forever! | 已矣哉, |

| —Li Sao, ending song (Owen, trans.)[10] |

The poem has a total of 373 lines[11] and close to 2500 characters, which makes it one of the longest poems dating from Ancient China. It is in the fu style.[11] The precise date of composition is unknown, it would seem to have written by Qu Yuan after his exile by King Huai; however, it seems to have been before Huai's captivity in the state of Qin began, in 299 BCE.

Reissue

[edit]The poem was reissued in the 19th century by Pan Zuyin (1830–90), a linguist who was a member of the Qing Dynasty staff. It was reissued as four volumes with two prefaces, with one by Xiao Yuncong.[12]

Translations into Western languages

[edit]- English

- E.H. Parker (1878–1879). "The Sadness of Separation or Li Sao". China Review 7: 309–14.

- James Legge (1895). The Chinese Classics (Oxford: Clarendon Press): 839–64.

- Lim Boon Keng (1935). The Li Sao: An Elegy on Encountering Sorrows by Ch'ü Yüan (Shanghai: Commercial Press): 62–98.

- David Hawkes (1959). Ch'u Tz'u: Songs of the South, an Ancient Chinese Anthology (Oxford: Clarendon Press): 21–34.

- Stephen Owen (1996). An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911 (New York: W.W. Norton): 162–75.

- Red Pine (2021). A Shaman's Lament (Empty Bowl).

- French

- Marie-Jean-Léon, Marquis d'Hervey de Saint Denys (1870). Le Li sao, poéme du IIIe siècle avant notre ére, traduit du chinois (Paris: Maisonneuve).

- J.-F. Rollin (1990). Li Sao, précédé de Jiu Ge et suivie de Tian Wen de Qu Yuan (Paris: Orphée/La Différence), 58–91.

- Italian

- G.M. Allegra (1938). Incontro al dolore di Kiu Yuan (Shanghai: ABC Press).

See also

[edit]- Chu Ci

- Kunlun Mountain (mythology)

- List of Chu Ci contents

- Liu An

- Liu Xiang (scholar)

- Qu Yuan

- Wang Yi (librarian)

- Wu (shaman)

- Xiao Yuncong

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Qu Yuan 屈原, alias Qu Ping 屈平.

References

[edit]- Citations

- ^ Zikpi (2014), p. 110, 114

- ^ Zikpi (2014), p. 137, 279, citing Cui & Li (2003), pp. 5–6: "'Li' is like 'to meet with'; 'Sao'is 'sorrow'; to express that he met with sorrow and composed the lyrics 離,猶遭也。騷,憂也。明己遭憂作辭也".

- ^ Su, Xuelin 苏雪林, ed. (2007). Chusao xingu 楚骚新诂. Wuhan University. p. 4.

离,犹遭也。骚,忧也

- ^ Owen (1996), p. 162.

- ^ Stephen Owen, An Anthology of Chinese Literature – Beginnings to 1911 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1996), 176.

- ^ Owen (1996), pp. 168–69.

- ^ Owen (1996), pp. 163–64.

- ^ Knechtges (2010), p. 145.

- ^ David Hawkes, Ch'u Tz'u: Songs of the South, an Ancient Chinese Anthology (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1959), 21.

- ^ Owen (1996), p. 175.

- ^ a b Davis (1970), p. xlvii.

- ^ "Illustrated Poem of Li Sao". World Digital Library. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- Works cited

- Cui, Fuzhang 崔富章; Li, Daming 李大明, eds. (2003). Chuci jijiao jishi 楚辭集校集釋 [Collected Collations and Commentaries on the Chuci]. Chuci xue wenku 楚辞学文库 1. Wuhan: Hubei jiaoyu chubanshe.

- Davis, A. R., ed. (1970). The Penguin Book of Chinese Verse. Baltimore: Penguin Books.

- Hawkes, David (1959). Ch'u Tz'u: Songs of the South, an Ancient Chinese Anthology. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hawkes, David, trans. (2011 [1985]). The Songs of the South: An Ancient Chinese Anthology of Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044375-2

- Hawkes, David (1993). "Ch'u tz'u 楚辭". In Loewe, Michael (ed.). Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. pp. 48–55. ISBN 1-55729-043-1.

- Hinton, David (2008). Classical Chinese Poetry: An Anthology. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-10536-7 / ISBN 978-0-374-10536-5

- Knechtges, David R. (2010). "Chu ci 楚辭 (Songs of Chu)". In Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping (eds.). Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide, Part One. Leiden: Brill. pp. 144–147. ISBN 978-90-04-19127-3.

- Owen, Stephen (1996). An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-97106-6.

- Yip, Wai-lim (1997). Chinese Poetry: An Anthology of Major Modes and Genres . (Durham and London: Duke University Press). ISBN 0-8223-1946-2

- Zikpi, Monica Eileen Mclellan (2014). Translating the Afterlives of Qu Yuan (PDF) (Ph. D.). New York: University of Oregon.

External links

[edit]- Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang, verse: full text, an English translation