Timeline of Brussels

| History of Belgium |

|---|

|

| Timeline • Military • Jewish history • LGBT |

The following is a timeline of the history of Brussels, Belgium.

Prehistory

[edit]- 10,000–2600 BCE – Polished silex from the Mesolithic era are located in the Nekkersgat.[1]

- 3000–2200 BCE – First known settlements in the region during the Neolithic era, located in the Sonian Forest.[2]

- 1000–800 BCE – Celtic tribes settle in what is now Brussels.[3]

Roman Period

[edit]

- A fairly important Roman settlement is in existence in Stalle.[1]

- 1st century CE – A Roman villa is constructed in Anderlecht, located near today's Allée de la Villa Romaine/Romeinse-Villadreef.[4]

- 2nd century CE – A Gallo-Roman villa is constructed in Jette, located in today's King Baudouin Park.[5]

- 175 CE – A Roman villa is in existence in Laeken.[3]

Middle Ages

[edit]- 4th–6th centuries CE

- Frankish tribes occupy territories between the Meuse and Scheldt rivers.[3]

- A Frankish tomb is built on the Zeecrabbeweg.[1]

- 580 – Saint Gaugericus builds a chapel on an island in the river Senne, laying the origin of the settlement which is to become Brussels.[6]

- 843 – 10 August: The region becomes part of Lotharingia after the signing of the Treaty of Verdun.[3]

- 870 – First mention of the County of Uccle or Brussels is made in the Treaty of Meerssen.

- 959 – The city becomes part of Lower Lotharingia.[3]

- 977–979 – A castrum is constructed on Saint-Géry/Sint-Goriks Island.[3]

- 979 – Charles, Duke of Lower Lorraine, transfers the relics of Saint Gudula to the chapel built by Saint Gaugericus, marking the city's official founding.

- 1001 – Otto, Duke of Lower Lorraine, becomes Count of Uccle or Brussels.[3]

- 1012 – Saint Guy dies in Anderlecht on his return home from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.[7]

- 1015–1020 – Oldest written record of the city is made by Olbert of Gembloux.[8]

- 1041–1047 – The Palace of Coudenberg begins construction.[3]

- 1047 – The relics of Saint Gudula are transferred from Moorsel to the original Church of St. Michael.[3]

- 1063–1100 – The city's first fortifications are built.

- 1095 – Dieleghem Abbey is first attested.

- 1105 – Forest Abbey is founded.

- 1125 – The Amman of Brussels is first attested.[3]

- 1129 – The Lindekemale Mill is first attested.

- 1142 or 1147 – The Battle of Ransbeek takes place.

- 1150 – St. Peter's Hospital is established as a leper colony, run by a community of lay brothers and sisters, in what was then a remote area far from the city's original walls..[9]

- 1174 – The Grand-Place/Grote Markt is first attested as the Forum inferior or Nedermerckt.[10]

- 1183 – The Duchy of Brabant is formed after the merger of the Counties of Uccle or Brussels and Leuven and the Landgraviate of Brabant.

- 1190 – Richard I of England passes through the city.[3]

- 1195 – Saint John Clinic is established.

- 1196 – La Cambre Abbey is founded.

- 1209 – The Lordship of Carloo is first attested.[1]

- 1213 – The Ancien Grand Serment royal et noble des Arbalétriers de Notre-Dame au Sablon schutterij of arbalists is founded.[11]

- 1225 – The current Church of St. Michael and St. Gudula begins construction.[3][12]

- 1229 – 10 June: Henry I, Duke of Brabant, issues a charter of rights for the city.[13]

- 1250 – The Great Beguinage of Brussels is formalised by John the Victorious.[14]

- 1252 – The Beguinage of Anderlecht is founded.

- 1253 – Karreveld Castle is first attested.

- 1258 – The Convent of Boetendael is first attested.[1]

- 1262 – The Priory of Val-Duchesse is established by Adelaide of Burgundy, Duchess of Brabant.

- 1267 – John the Victorious relocates the capital of the Duchy of Brabant from Leuven to the city.

- 1282 – First mention of the Drapery Court and the Wise Council is made.[3]

- 1290 – 18 June: The hermit Mary the Miserable is buried alive for theft and witchcraft, with a chapel later built on her burial site.

- 1292 – John the Victorious grants the town the right to revenues collected at the city gates.[3]

- 1295 – John the Peaceful authorises aldermen to collect duty on beer as a town revenue.[3]

- 1296 – 14 February: Obbrussel becomes part of the Coop of Brussels.

- 1303–1306

- An unsuccessful revolt by the Guilds of Brussels to secure power-sharing with the patriciate takes place.

- The first democratic government is established.[3]

- 1304 – The Church of Our Blessed Lady of the Sablon is founded.[15]

- 1306 – The Seven Noble Houses of Brussels are first attested.[3]

- 1308 – The Meyboom is first attested.[16]

- 1318 – John of Ruusbroec becomes a parish priest at the Church of St. Michael and St. Gudula together with his uncle Jan Hinckaert.

- 1321 – Dry Borren is first attested as a hermitage.

- 1335 – 23 August: The Christian mystic Heilwige Bloemardinne, considered the city's first feminist, dies.[17]

- 1342 – The city bans the construction of thatched roofs to prevent fires.[18]

- 1348 – The Ommegang begins as a Marian procession.[19]

- 1349

- 1356

- The Joyous Entry of Joanna and Wenceslaus into the city takes place.

- 17 August: Battle of Scheut: Louis II, Count of Flanders defeats Joanna, Duchess of Brabant, who then besieges the city.

- 24 October – The city is liberated by group of Brabantian patriots led by Everard 't Serclaes, Lord of Kruikenburg.[3]

- The expansion of the city's fortifications begins.

- 1360–1364 – Unsuccessful revolts by the Guilds to secure power-sharing with the patriciate take place.

- 1368 – Jan Collaey donates land near the Droge Heergracht to the Alexians, on what is now Rue des Alexiens/Cellebroedersstraat.[21]

- 1367 – The Red Cloister is founded.[3]

- 1370 – 22 May: The Sacrament of Miracle occurs, killing 6–20, followed by the expulsion of the city's remaining Jewish population.

- 1380 – Geert Pipenpoy becomes the city's first mayor.

- 1381 – The Grand Serment des Arbalétriers de Bruxelles and Serment de Saint-Georges schutterijen of arbalists and archers are founded by the Duchess of Brabant.[22]

- 1383 – The original Halle Gate is built.

- 1388 – 31 March: Everard t'Serclaes dies at the L'Étoile/De Sterre guildhall on the Grand-Place.

- 1400 – Population: c. 20,000.[3]

- 1401 – The Town Hall begins construction on the Grand-Place.

- 1406

- The Joyous Entry of Anthony the Great Bastard into the city takes place.[3]

- 14 April: A fire destroys part of the Chapel Church and the surrounding neighbourhood.[18]

- 1411 – 12 June: The Homines Intelligentiae, supposedly founded by Ægidius Cantor, is first mentioned in an ecclesiastical ruling by Pierre d'Ailly, and are prosecuted, resulting in the imprisonment and exile of William of Hildernissen, though the overall outcome is unknown.

- 1420 – 5 February: Den Boeck chamber of rhetoric is recognised by John IV, Duke of Brabant.

- 1421

- 1424 – The city's aldermen issue the earliest known municipal regulation in the Low Countries on medicine and midwifery, detailing qualifications for doctors and midwives.[24]

- 1436 – Rogier van der Weyden is appointed city artist.[3]

- 1455

- The Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament of the Miracle is built.

- The Town Hall is completed.[3]

- 1457 – The Dominicans are authorized to establish a presence in the city and relocate to Lange Ridderstraete.[25]

- 1464 – Population: c. 39,000.[3]

- 1476 – The first printing press is in operation in the city.[26]

- 1477

- The Habsburgs come to power in the Burgundian Netherlands, with the city as their capital.[27]

- March: A popular insurrection under Willem van Marbais, Jan Bogaert and Willem van Ruysbroeck takes place.[3]

- 4 June: The Joyous Entry of Mary of Burgundy into the city takes place.

- 1479 – 13 October: De Corenbloem chamber of rhetoric is first attested.[28]

- 1480 – The Serment royal des Saints-Michel-et-Gudule ou des Escrimeurs de Bruxelles schutterij of archers and fencers is established.[29]

- 1486

- De Lelie chamber of rhetoric is first attested following the Joyous Entry of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor.[30]

- 6 May: De Violette chamber of rhetoric is first attested.[31]

- 1499 – 25 February: The Brotherhood of Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows is established by members of De Lelie and De Violette.

16th & 17th centuries

[edit]- 1507 – 15 September: 't Mariacranske chamber of rhetoric is established following the merger of De Lelie and De Violette, with Jan Smeken becoming its first factor.[32]

- 1511 – The Miracle of 1511 takes place.

- 1515 – 28 January: The Joyous Entry of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and Philip the Prudent into the city takes place.

- 1516 – 4 December: The Treaty of Brussels is signed, ending the War of the League of Cambrai.

- 1521 – May–October: Erasmus moves to Anderlecht for health, political, and religious reasons and stays in the house of Canon Peter Wijchmans.

- 1522

- September: The Amigo Prison is built.

- 8 February: The Treaty of Brussels between Charles V and Archduke Ferdinand, concerning the latter's sovereignty over the Austrian Hereditary Lands, is signed.

- 1523 – 1 July: Jan van Essen and Hendrik Vos are burned at the stake at the Grand-Place, becoming the first victims of the Inquisition in the Netherlands.

- 1526 – 20 October: A fire destroys three houses in the Rue des Six Jetons/Zespenningenstraat.[18]

- 1528 – 15 September: The body Lambrecht Thorn, a collaborator of Jan van Essen and Hendrik Vos, dies in captivity.

- 1536 – The original King's House is built on the Grand-Place for the Duke of Brabant.[33]

- 1539 – 3 January: The Supreme Charity is established in response to Charles V's 7 October 1531 edict, which banned begging and centralised town welfare revenue to combat pauperism.[34]

- 1543 – Brussels lace is explicitly mentioned for the first time in a list of presents given to Princess Mary for New Year's.[35]

- 1544 – Andreas Vesalius marries Anna van Hamme and has a daughter, moving into a large estate in Hellestraetken, near today’s Rue des Minimes/Minimenstraat.

- 1555 – 25 October: Charles V abdicates in the Aula Magna of the Palace of Coudenberg.[3]

- 1561 – 12 October: The city's port and the Willebroek Canal are opened.[36]

- 1565 – 11 November: The wedding of Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, and Maria of Portugal, Hereditary Princess of Parma, takes place.[37]

- 1566 – 5 April: The signatories of the Petition of the Nobles gain access to the Palace of Coudenberg to present it to Margaret of Parma.

- 1567

- 22 August: Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba, arrives in the city.[3]

- 30 August: Margaret of Parma resigns as Governess of the Netherlands and flees the city.

- 9 September: The Council of Troubles is established.

- 1568

- 1 June: Eighteen signatories members the Compromise of Nobles are decapitated at the Peerdemerct.[3]

- 5 June: The Counts of Egmont and Horn are executed at the Grand-Place.

- 1575 – A plague outbreak kills thousands.[3]

- 1576 – 4 September: The Calvinist Republic of Brussels is founded following the imprisonment of the Council of State and the Secret Council.

- 1577 – 24 September: The Joyous Entry of William the Silent into the city takes place.

- 1579 – 6 June: The Great Beguinage is looted by Scottish auxiliary troops as part of the larger Beeldenstorm.[38]

- 1580

- 1 May: All public displays of Catholicism are banned.[39]

- 9–10 July: The city tries to capture Halle under the command of Olivier van den Tympel.

- 1585 – 10 March: The city is besieged by the Army of Flanders.[40][41]

- 1587 – 20 July: During a mystery play performed by the Brethren of the Common Life, a lodge collapsed, killing the author Petrus Fabri and alderman Eustachius Pipenpoy, and injuring several spectators.[42]

- 1589 – October: The city grants the Augustinians a tax exemption in exchange for holding mass at the town hall for three months each year and serving as firemen when needed.[43]

- 1590 – 31 March: The city decides to construct the Simpelhuys, a complex featuring residential blocks, kitchens, a bakery, and sixty dedicated cells for individuals with mental health needs.[44]

- 1594

- 30 January: The Joyous Entry of Archduke Ernest of Austria into the city takes place.[45]

- 21 December: Anna Utenhoven, arrested with Anna and Catharina Rampaerts, was found guilty of heresy and buried alive on the Haerenheyde, becoming the last person executed for heresy in the Low Countries.

- 1595

- The Kaiserliche Reichspost postal service is established in the city.

- 13 September: Josyne van Beethoven is burned at the stake at the Grand-Place for wichcraft.[46]

- 1599

- 13 July: An ordinance mandates that slackers are both to be branded and flogged.[47]

- 5 September: The Joyous Entry of Albert VII, Archduke of Austria, and Isabella Clara Eugenia into the city takes place.[3]

- 1604 – 16 July: St John Berchmans College is established.

- 1607 – The Brussels Carmel is founded.

- 1618 – 28 September: The Mount of Piety of Brussels opens.

- 1619

- The original Manneken Pis statue is commissioned.

- 12 July: A riot breaks out after the city imposes a tax on wine and beer (the gigot).[3]

- 1622 – The funeral of Archduke Albert VII takes place.

- 1625 – The Deuchthuys opens to force beggars, slackers, and vagrants to produce textile goods, with Daniel Sirejacobs serving as its first director.[48]

- 1631 – The Royal Grand Brotherhood of St Guido is first attested.[49][50]

- 1646

- The Small Beguinage of Brussels is founded.

- 6 October: Purple rain falls on the city; the downpour elicits scientific examination and explanation.[3]

- 1654 – The Barony of Jette is formed.[51]

- 1657 – De Wijngaard theatre company is established, possibly out of 't Mariacranske.[52]

- 1659 – The Barony of Jette is elevated to a county.[51]

- 1668

- 7 June: The city enacts an ordinance to combat the Black Death and appoints a Plague Master to oversee the care of the sick.[53]

- 27 July: To prevent the spread of the Black Death, the city restricts movement to evenings, bans gatherings, and prohibits the sale of certain foods, while confiscating and destroying grain, flour, and meat.[53]

- 1670 – 7 January: A posthumous mass is held in honor of the victims of the Black Death.[53]

- 1672 – The Fort of Monterey is built.

- 1682 – 24 January: The Opéra du Quai au Foin opens as the first public theatre in the city.

- 1690 – 11–12 October: A fire breaks out in La Louve/De Wolvin guildhall on the Grand-Place.

- 1695 – 13–15 August: The city is bombarded by the French, destroying a third of its buildings, including the Grand-Place.

- 1697–1698: Reconstruction of the Grand-Place is largely completed.[3]

- 1698 – 1 May: Manneken Pis receives his first costume from the Governor of the Austrian Netherlands, Maximilian II Emanuel of Bavaria.[54][55]

- 1700 – 17 October: The first Theatre of La Monnaie, then spelled La Monnoye, opens.

18th century

[edit]- 1701 – The Nassau Palace suffers extensive damage from a fire.

- 1703 – 3 February: The Chamber of Commerce and Industry is founded by Isidro de la Cueva y Benavides, much to the displeasure of the Drapery Court.[56]

- 1705 – The Fort Jaco is built.

- 1706 – The English–Dutch army enters the city.[3]

- 1711 – 30 September: The Royal Academy of Fine Arts is established.[3]

- 1714

- March 6: The Treaty of Rastatt is signed; the city becomes part of the Austrian Netherlands.[3]

- 25 July: The Belfry of Brussels collapses.

- 1717 – 14–18 April: Peter the Great visits the city.[3][57]

- 1719 – 19 September: François Anneessens is executed at the Grand-Place.

- 1724 – March: The Senne floods: The lower city is 3 feet underwater.[58]

- 1731 – 3–4 February: The Palace of Coudenberg is destroyed by fire.[3]

- 1733 – 10 February: The city instructs gravediggers to bury corpses at least three feet deep to prevent dogs from uncovering them and causing infections.[21]

- 1744 – Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine enters the city.

- 1746 – 29 January–22 February: The city is besieged and captured by the French.

- 1749 – January: The city is returned to Austria with the rest of the Austrian Netherlands following the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle.

- 1755 – Population: 57,370.[3]

- 1769 – Vanparys Confiserie is established by Felix Vanparys.

- 1771–1778 – Au Vieux Spijtigen Duivel is first attested on the Ferraris map.

- 1772

- The Opéra flamand is established.

- Faro is first attested.

- 16 December: The Imperial and Royal Academy is established.[59]

- 1774 – The Rue Royale/Koningsstraat is laid out.[15]

- 1775

- Brussels Park is laid out.

- The Place des Martyrs/Martelaarsplein, then called the Place Saint-Michel/Sint-Michielsplein, is laid out.[3]

- 1778 – The Palace of the Nation begins construction.

- 1779 – The Brussels Arsenal is built.

- 1781 – Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor visits the city.

- 1782

- The Place Royale/Koningsplein is laid out.

- 1 May: The brothers Alexandre and Herman Bultos receive permission to construct the Royal Park Theatre as an annex to the Theatre of La Monnaie.[60]

- 1787 – The Vauxhall opens.

- 1783 – The Royal Palace of Brussels begins construction.

- 1784

- The city's gates are demolished, except for the Halle Gate.

- The Palace of Schonenberg is built.

- 1787 – 29 October: The Church of St. James on Coudenberg is consecrated.

- 1789 – The Brabant Revolution reaches the city and makes the Austrian authorities flee.

- 1790

- 10 January: Albert Casimir and Maria Christina, the Governors of the Austrian Netherlands, flee the city to Vienna.[61]

- 11 January: The city becomes the capital of the United Belgian States.

- 6 October: Willem van Criekinge is lynched after insulting the Capuchin Josse Huyghe during a Marian procession.

- 2 December: The Austrians take the city back and pledge to reverse the reforms of Joseph II.

- 1792 – 14 November: General Charles-François Dumouriez enters the city.[3]

- 1795 – 1 October: The French rule begins; the city becomes the chef-lieu of the department of the Dyle.

- 1796

- The Guilds of Brussels are suppressed.[62]

- La Cambre Abbey and Forest Abbey are abolished.

- The Church of St. Gaugericus is demolished.

- 1800

- Population: 66,297.[3]

- 10 January: The Société de littérature de Bruxelles literary society is established.

19th century

[edit]- 1801 – 8 July: The Brussels Stock Exchange is founded by decree of First Consul Napoleon.[3]

- 1803

- The Museum of Fine Arts opens.[63]

- Napoleon visits the city.[3]

- 1805 – D'Ieteren is established by the master coachbuilder Joseph-Jean D'Ieteren.

- 1806 – 25 March: The Academy of Brussels, an academy of the Imperial University of France, is established.

- 1810

- Emperor Napoleon officially visits the city.[3]

- 19 May: An ordinance is issued to build the Small Ring.[3]

- 14 December: The Bar Association of Brussels is established by imperial decree.

- 1811 – 4 November: The first Brussels Salon is held.

- 1813 – The Royal Conservatory of Brussels is founded.

- 1815

- 15 June: The Duchess of Richmond's ball takes place.

- 24 August: The city becomes the joint capital of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands.

- 1817: 19 February: William III of the Netherlands is born in the Palace of the Nation.

- 1819

- The city is claims Jean-Baptiste Van Mons' experimental La Fidélité orchard, once the city's largest, to subdivide it.[64]

- 25 May: The new Theatre of La Monnaie is inaugurated.

- The city is illuminated by gas.[3]

- 1821

- De Wijngaard is integrated into 't Mariacranske.[65]

- The liberal Courrier des Pays-Bas newspaper starts publication succeeding Vrai Libéral.

- 1822 – The Société générale de Belgique is headquartered in the city.[66]

- 1823 – The Société des douze is established as a continuation of the Société de littérature de Bruxelles.

- 1826

- 8 June: The Royal Observatory of Belgium is founded by King William I of the Netherlands under the impulse of Adolphe Quetelet.

- 1829

- The Delvaux leather luxury goods brand is established by Charles Delvaux.

- Maison Dandoy biscuiterie is established on the Rue au Beurre/Boterstraat by Jean-Baptiste Dandoy.

- 1 September: The Botanical Garden of Brussels opens.

- 1830

- Population: 98,279 city; 120,981 metro.[67]

- The Établissement géographique de Bruxelles is founded by Philippe Vandermaelen.

- The Royal Theatre Toone is founded.

- 25 August: The Belgian Revolution starts in the city.[68]

- 22 October: Nicolas-Jean Rouppe is appointed the first Mayor of Brussels in an independent Belgium by royal decree.

- 1831

- 7 February: The Constitution of Belgium is ratified; the city becomes the capital of the Kingdom of Belgium.[27]

- 25 February: Érasme-Louis Surlet de Chokier takes the constitutional oath at the Palace of the Nation.

- 21 July: King Leopold I takes the constitutional oath at the Place Royale/Koningsplein.

- 1832

- A cholera epidemic kills over 3,000.[3]

- 22 September: The Brussels–Charleroi Canal opens.[69]

- 1833 – 23 February: The Grand Orient of Belgium secedes from the Grand Orient of the Netherlands.

- 1834

- 7 February: The Royal Military Academy is founded.

- 5–6 April: The city's nobility is looted by pro-Belgian protesters on the Orangist nobility.

- 20 November: The Free University of Brussels is founded.[3]

- 1835 – 5 May: The first passenger train on a public railway in continental Europe departs from the Allée Verte/Groendreef railway station.

- 1936 – 22 February: The Brussels Meridian is installed in the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula.

- 1837

- The Bollandist Society is reestablished under the patronage of the Belgian Government.

- 19 June: The Royal Library of Belgium is founded.[70]

- 1838 – 13 September: Guillaume-Hippolyte van Volxem is appointed mayor by royal decree.

- 1841 – 14 April: François-Jean Wyns de Raucour is appointed mayor by royal decree.

- 1842

- Charlotte and Emily Brontë enroll at the boarding school run by Constantin Héger, located at what is now the Centre for Fine Arts.

- 8 February: The Cercle du Parc private club is established when a group of Belgicist noblemen left the Orangist Cercle de l'Union.[71]

- 1844 – The Belgian-Bavarian friturist Jean Frédéric Krieger, also known as Monsieur Fritz, opens Fritz à l'instar Paris, the first friterie in the city.[72]

- 1845

- Saint Mary's Royal Church begins construction.

- The first telegraph line links the city with Antwerp.[3]

- 1846

- Population: 123,874 city.[73]

- 31 March: The Museum of Natural Sciences is founded.

- 24 September: The Société Pantechnique et Palingénésique des Agathopèdes is founded by Antoine Schayes.

- 1847

- The Avenue Louise/Louizalaan is commissioned.

- May: Systematic construction of sidewalks begins.[3]

- 20 June: The Royal Saint-Hubert Galleries open alongside the Théâtre Royal des Galeries.[3]

- August: The German Workers' Society is founded in the city by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels.

- 1848

- September: The second International Peace Congress is held in the city.

- 5 October: Charles de Brouckère becomes mayor.

- 23 November: The Cercle artistique et littéraire de Bruxelles artist collective is established with Adolphe Quetelet as its first president.

- 1850

- Population: 142,289 city; 222,424 metro.[67]

- 5 May: The National Bank of Belgium is established by Minister Walthère Frère-Orban, replacing the Société générale de Belgique as fiscal agent of the Belgian Government.

- 1851 – 6 October: The École moyenne A is founded within the Free University of Brussels.[74]

- 1852 – The Tooneel der Volksbeschouwing is established as a permanent Flemish theatre company in the city.

- 1853 – 7 April: The European Quarter is annexed from Saint-Josse-ten-Noode, Etterbeek and Schaerbeek by the City of Brussels.

- 1855

- Brussels-Luxembourg railway station is built.

- The last public execution is held at the Halle Gate.[3]

- 1856

- 28 March: The reconstructed Royal Theatre of La Monnaie opens.

- 11 June: The Société royale belge des aquarellistes is founded under the chairmanship of Jean-Baptiste Madou.

- 1857

- The Ancienne Belgique opens.

- Saint-Louis University moves to the city from Mechelen.

- The first municipal water service is established.[3]

- 1859 – The Congress Column is erected.

- 1860

- Population: 185,982 city; 300,341 metro.[67]

- Duties and tolls on goods entering the city are abolished.

- 21 April: André-Napoléon Fontainas becomes mayor.

- 1861 – The Bois de la Cambre/Ter Kamerenbos is laid out.

- 1862 – 28 November: The Congregation of the Immaculate Heart of Mary is established in Scheut by Théophile Verbist.

- 1863 – 15 December: Jules Anspach is appointed mayor by royal decree.[3]

- 1864

- The Avenue Louise and Bois de la Cambre are annexed from Ixelles by the City of Brussels.

- The first Luizenmolen is build.

- 26 September: Nadar launches the hot air balloon Le Géant from the Botanical Garden. To ensure the crowd's safety, Jules Anspach erects mobile barriers, thereby inventing crowd control barriers.

- 3 October: The Isabelle Gatti de Gamond Royal Atheneum is established as the first non-denominational educational institution for girls in Belgium.

- 1865 – 17 December: King Leopold II takes the constitutional oath at the Palace of the Nation.

- 1866 – Population: 157,905 city.[3]

- 1867

- The covering of the Senne begins.

- The Legend of Thyl Ulenspiegel and Lamme Goedzak is published by Charles De Coster.

- The Grand Serment royal et de Saint-Georges des Arbalétriers de Bruxelles is established as a continuation of the Grand Serment des Arbalétriers de Bruxelles and Serment de Saint-Georges schutterijen.

- Witlof is sold for the first time in a market, likely the New Market at the steps of the Congress Column, after being created by Frans Bresiers.

- 1868

- The Antoine Wiertz Museum opens.

- 1 March: The Société Libre des Beaux-Arts is established.

- 1869 – 1 May: Trams begin operating in the city.

- 1871

- The covering of the Senne is completed; the Central Boulevards are laid out.

- The Bank of Brussels is established.[66]

- The Halle Gate is renovated in the neo-Gothic style.[75]

- 27–28 May: A protest erupts at Victor Hugo's house in Barricadenplein/Place des Barricades after he writes an open letter denouncing the Belgian government for fearing the arrival of Paris Communards. A week later, he is expelled from the country.[76]

- 1872 – The Church of Our Lady of Laeken is consecrated.

- 1873

- The new building for the Brussels Stock Exchange is completed.

- The daily Old Market on the Place du Jeu de Balle/Vossenplein is established.

- The Concert Noble opens in the Leopold Quarter.

- 10 July: In a drunken rage, Paul Verlaine shoots Arthur Rimbaud, wounding him in the left wrist with a revolver he had purchased earlier that day.[77]

- 1874

- The Royal Greenhouses of Laeken begin construction.

- Brussels Cemetery is laid out.

- The Ateliers Mommen are established by the ébéniste Félix Mommen, becoming the oldest art commune in the city.

- 2 May: The first Conference of Mayors is held.[78]

- 23 December: Les Tramways Bruxellois is formed.

- 1875 – The Panopticum de Maurice Castan opens on the Place de la Monnaie/Muntplein.

- 1876 – The Noirauds children's charity is founded by Jean Bosquet and friends.[79]

- 1877

- The Anderlecht Municipal Hall is built.[80]

- Ixelles Cemetery is created.

- 6 May: The Musical Instruments Museum opens.

- 1878

- 12 January: The Cirque Royal/Koninklijk Circus opens.

- 20 September: The Great Synagogue of Brussels is consecrated.

- 1879 – 20 May: Felix Vanderstraeten is appointed mayor by royal decree.

- 1880

- A National Exhibition is held to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Belgian independence;[3] the Parc du Cinquantenaire/Jubelpark is laid out.

- The White slave trade affair scandal is exposed and attracts international attention.

- The Midi Fair begins.

- 1881

- L'Echo newspaper begins its publication.[81]

- 17 December: Charles Buls is appointed mayor by royal decree.

- 1882 – 7 January: The accountant Guillaume Bernays is killed by Léon Peltzer on behalf of his brother Armand Peltzer at 159, rue de la Loi/Wetstraat.

- 1883

- 15 October: The Palace of Justice of Brussels is inaugurated.

- 28 October: Les XX artistic society is founded by Octave Maus.

- 1884 – 3 September: 80,000 Catholics gather in support of the Law Jacobs. Local residents disperse them by dumping sacks of laundry bluing.[3]

- 1885

- Population: 171,751 city.[73]

- The Beursschouwburg opens as the Brasserie flamande.[82]

- 15 June: Saint-Gilles Prison opens.[3]

- 1886

- The city is linked by telephone to Paris.[3]

- Le Cirio café is established on the Rue de la Bourse/Beursstraat by Francesco Cirio.

- 1887

- Le Soir newspaper begins its publication.[81]

- The Palace for Fine Arts is built.

- The Brussels City Museum opens in the King's House.

- The Schaerbeek Municipal Hall is built.[83]

- 16 June: The Société d'Archéologie de Bruxelles is established.

- 1 October: The Brussels Arsenal reopens as the Royal Flemish Theatre.

- 1888

- Het Laatste Nieuws newspaper begins its publication.[81]

- 24 November: The first Saint Verhaegen/Sint-Verhaegen takes place as a student protest against a reorganisation of the Free University.

- 1889

- The Molenbeek-Saint-Jean Municipal Hall is built.[84]

- 18 November: The Brussels Anti-Slavery Conference begins.

- 1890

- The Abattoirs of Anderlecht enter service as a central abattoir for the whole city.

- The Square du Petit Sablon/Kleine Zavelsquare is laid out.

- 1891

- August: The International Socialist Labor Congress is held in the city.

- 12 December: The Compagnie intercommunale des eaux de l'Agglomération bruxelloise (CIE) is established.

- 1892

- La Paix restaurant is established.

- 27 November: The Belgian League for the Rights of Women is established by Marie Popelin and her lawyer Louis Frank.

- 1893

- The Paris–Brussels cycle race begins.[85]

- The Hôtel Tassel is built.

- The Hankar House is built.

- The Autrique House is built.

- Chez Léon is established, laying the basis for the French restaurant chain Léon de Bruxelles.

- 11–18 April: The Belgian general strike of 1893 is called after politicians of Catholic and Liberal parties joined to block a proposal to expand the suffrage.[86]

- 29 October: La Libre Esthétique artistic society is founded by Octave Maus as a successor of Les XX.

- 1894

- The Société Belge d'Études Coloniales is headquartered in the city.

- 4 February: The first Scharnaval is held.[87]

- 25 October: The New University of Brussels is established after Élisée Reclus was barred from teaching for political reasons, prompting liberal and socialist faculty members from the Free University to plan an independent institution.

- 1895 – The Hotel Métropole opens at the Place de Brouckère/De Brouckèreplein.

- 1896

- The King's House is rebuilt in the neo-Gothic style.

- The Villa Bloemenwerf is built.

- 1 March: The first public showing of moving pictures takes place in the Royal Saint-Hubert Galleries.

- 1897

- The Avenue de Tervueren/Tervurenlaan is laid out.

- The Oriental Pavilion is built.

- 10 May–8 November: The Brussels International world's fair is held.

- 1 November: Royale Union Saint-Gilloise is founded.

- 16 December: Emile De Mot is appointed mayor by royal decree.

- 1898 – The Saint Roch Quarter is demolished.

- 1899

- 2 April: The Maison du Peuple/Volkshuis is opened by the Belgian Labour Party.[88]

- 28–29 June: The June Riots erupt, after a Catholic proposal to rewrite the electoral law in their favour leads to tumultuous parliamentary debates.

- 1 October: The Pavilion of Human Passions is inaugurated.

- 1900

- Population: 183,686 city.[3]

- The Cantillon brewery is founded.

- New Saint John Clinic is built.[89]

- 4 April: Edward, Prince of Wales, is shot at by Jean-Baptiste Sipido at Brussels-North railway station.[3]

20th century

[edit]1901–1913 – La Belle Époque

[edit]- 1901 – The Maison & Atelier Horta is built.

- 1902

- À la Mort Subite café is built.

- The Sino-Belgian Bank is established at the request of King Leopold II.

- 12 April: Riots erupt in the Marolles/Marollen during the Belgian general strike of 1902.

- 15 November: An attempted assassination of King Leopold II by Gennaro Rubino takes place.

- 1903 – Le Falstaff café is built.

- 1904

- The Saint-Gilles Municipal Hall is built.[90]

- 26 June: Josaphat Park opens.

- 1905

- The Cauchie House is built.

- Busses begin operating in the city.[3]

- 21 September: St. Michael's College opens in Etterbeek.

- 25 September: The Cinquantenaire Arcade is completed.[3]

- 1906

- 13 January: Besix is founded by the Stulemeijer family.

- 7 February: The dismembered body of Jeanne Van Calck is found at 22, rue des Hirondelles/Zwaluwenstraat.

- 24 February: Chilean diplomat Ernesto Balmaceda Bello is shot and killed by Carlos Waddington, the brother of his fiancé Adelaida Waddington.

- 2 May: The Yachting Club de Bruxelles is established.

- 1908

- The Chapel of the Resurrection is built.

- 27 May: R.S.C. Anderlecht is founded.

- 1909

- 6 December: Adolphe Max is appointed mayor by royal decree.

- 23 December: King Albert I takes the constitutional oath at the Palace of the Nation.

- 1910

- The Hôtel Astoria opens.

- 10 March: Le Mariage de mademoiselle Beulemans is first preformed at the Théâtre de l'Olympia.

- 23 April–1 November: The Brussels International world's fair is held.

- 1911

- The Stoclet Palace is built.

- The North–South connection begins construction.[3]

- 16–17 April: The Schaerbeek Municipal Hall is partially destroyed by a suspected arson fire.[83]

- 30 October–3 November: The first Solvay Conference is held.

- 23 December: The Cercle de la Toison d'Or private club is founded.

- 1913

- The Belle-Vue Brewery is established.

- 14–24 April: The Belgian general strike of 1913 takes place.

1914–1918 – First World War

[edit]

- 1914

- 1 May: Tram line 81 begins service.

- 11 May–4 June: The Great Zwanz Exhibition is held.

- 21 August: World War I: The city is captured and occupied by the German Army.[3]

- 26 August: The city becomes the seat of the Imperial German General Government of Belgium.

- The Imperial German Air Service establishes Flugplatz Brüssel military airfield in Haren.

- 1915

- 7 June: A Zeppelin hangar on Flugplatz Brüssel is partially destroyed during an attack on airship LZ38.

- 12 October: Edith Cavell is executed by firing squad at the Tir National/Nationale Schietbaan.

- 1917 – The Constant Vanden Stock Stadium opens.

- 1916 – 1 April: Gabrielle Petit is executed by firing squad at the Tir National.

- 1918

- 10 November: The Brussels Soldiers' Council is established by German troops in German-occupied Belgium.

- 22 November: King Albert I returns to the city.

1919–1939 – Interwar period

[edit]- 1919

- Population: 685,268 metro.[91]

- The Lignes Farman airline begins operating its Paris–Brussels route.[92]

- The New University is reintegrated into the Free University.

- 1920

- The Oscar Bossaert Stadium opens.

- The Mundaneum opens.

- 15–26 August: The fencing events of the Games of the VII Olympiad are held at Egmont Palace.[93]

- 20 August: Belga news agency is established by Pierre-Marie Olivier and Maurice Travailleur in Schaerbeek.

- 28 August–5 September: Some of the football events of the Games of the VII Olympiad are held in the Joseph Marien Stadium.[94]

- 1921 – 30 March: Haren, Laeken and Neder-Over-Heembeek are annexed by the City of Brussels.[3]

- 1922

- The Experimental Garden Jean Massart is established.[95]

- 12 November: Tour & Taxis officially opens. [96]

- 1923

- The Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and Military History opens.

- Brugmann Hospital opens.

- 1 January: The Vlaamse Club voor Kunsten, Wetenschappen en Letteren is established.

- 2 January: Tram line 23 begins service.

- 23 May: The Societé anonyme belge d'Exploitation de la Navigation aérienne (Sabena) is established.[3]

- 1925 – St Andrew's Church is consecrated.

- 1926

- The École nationale supérieure des arts visuels de La Cambre (ENSAV) is established.

- The Comme chez Soi restaurant is established.

- 1927 – 24–29 October: The fifth Solvay Conference, perhaps the most famous, is held.

- 1928

- The Charlier Museum opens.

- The Villa van Buuren is built.[97]

- 1929

- 4 January: Tintin first appears in Le Petit Vingtième newspaper.

- 19 October: The Centre for Fine Arts opens.

- 1930

- Population: 200,433 city.[3]

- The Hotel Le Plaza opens.

- 18 June: The National Institute for Radio Broadcast (NIR) is established.

- 23 August: The Jubilee Stadium opens.

- 1931 – The Brussels Symphony Orchestra is founded.

- 1932 – 7 October: The Luna-Theater opens on the site of a former luna park.[98]

- 1933 – 6 April: The Synagogue of Anderlecht is consecrated.

- 1934

- The Villa Empain is built.

- The Citroën Garage is built.

- 22 February: The funeral of King Albert I takes place.

- 23 February: King Leopold III takes the constitutional oath at the Palace of the Nation.

- 1935

- The Brussels International world's fair is held; the Palais des Expositions is built.

- The Basilica of the Sacred Heart is consecrated.

- 1937 – The Queen Elisabeth Competition begins.

- 1938

- The Royal Belgian Film Archive is established.

- The Forest Municipal Hall is built.[99]

- The Flagey Building is built.

- Scabal is established as a cloth merchant and supplier of fabrics by Otto Hertz.

- 28 February: Bossemans et Coppenolle is first preformed at the Théâtre du Vaudeville.

- 1939

- The Constantin Meunier Museum opens.

- 28 November: Joseph Van De Meulebroeck is appointed mayor by royal decree.

1940–1945 – Second World War

[edit]

- 1940

- 17 May: World War II: The German occupation begins;[3] the Belgian Government flees the city to Bordeaux.[100]

- 31 May: The German Military Administration in Belgium and Northern France is headquartered in the city.[100][101]

- 1 July: The Zéro intelligence network in formed by employees of the Bank of Brussels.[100]

- 20 July: The Frontstalag 110 prisoner-of-war camp is established by the Germans.[102][103]

- 31 July: The Radio Bruxelles and Zender Brussel radio stations are established by the Military Administration.[100]

- 15 August: La Libre Belgique clandestine newspaper begins its publication.[100]

- 17 December: The Belgian National Movement is established.[100]

- 1941

- 1 February: Le Drapeau Rouge and De Roode Vaan clandestine newspapers begin their publication by the Communist Party of Belgium.[100]

- 13 March: The Frontstalag 110 POW camp is dissolved.[102][103]

- 29 May: The 'Hunger march for the release of prisoners of war', 3,000 women rally behind slogans and march through the city.[100]

- June: A passenger train derails in Uccle after a failed sabotage attempt by the Belgian National Movement of a tank transport from Charleroi on line 154.[104]

- 30 June: Joseph Van De Meulebroeck is arrested and deported; Jules Coelst is designated deputy mayor.

- 18 August: The Comet Line starts operating.[105]

- 10 October: Bombing of the Rex headquarters on the Rue de Laeken/Lakensestraat; Jean-Joseph Oedekerken is killed.[100]

- 25 November: The Free University of Brussels closes.[100][106]

- 1942

- January: Groupe G is formed by a group of former students of the Free University.

- 10 March: Violence erupts in the city during a parade of the Walloon Legion before leaving for the Eastern Front, marked by bombings and attacks from communist militants against collaborators and military targets.[107]

- 3 September: A razzia occurs in the Marolles, 718 are arrested and transported to Dossin.[108]

- 24 September: Greater Brussels is formed by merging 18 municipalities into the City of Brussels; Jan Grauls is appointed mayor.[100]

- 1943

- 20 January: An attack on the Gestapo headquarters by Baron Jean de Selys Longchamps takes place.

- 14 April: Paul Colin is assassinated by Arnaud Fraiteur.[109]

- 27 April: A failed assassination attempt on Icek Glogowski, occurs at his residence on Rue Vanderkindere/Vanderkinderestraat when a pistol jams, after which he is transported daily by the Gestapo.

- 7 September: The city is bombarded by the Allies, killing 342.

- 1944

- 28 February: Alexandre Galopin is assassinated by Flemish collaborators from DeVlag.

- 1 August: Attacks in the city against the Germans and collaborators take place; they retaliate and execute 30 people.[100]

- 23 August: 15 people are executed by the Germans.[100]

- 3–4 September: The city is liberated by the Welsh Guards; the Palace of Justice is burnt by the Germans to destroy legal records during their retreat.

- 8 September: The Belgian Government in exile returns to the city after four years in London.

- 20 September: Prince Charles, Count of Flanders takes the constitutional oath at the Palace of the Nation, and becomes regent.[110]

- 20 November: The Free University reopens.

- 15 December: The District of Brussels, formed by Nazi Germany, is no longer in control of the territory.

- 1945 – 10 June: A mock funeral procession for Adolf Hitler is held in the Marolles, during which funds were raised to support the victims of Auschwitz.[111][112]

1946–1979 – Post-war era

[edit]- 1946 – Tintin comics magazine starts publication by Le Lombard.

- 1948

- The Treaty of Brussels, founding the Western Union (WU), is signed.

- Brussels Airport opens in Zaventem.

- 1950

- 1 August: King Leopold III asks the Government and Parliament to vote on a law delegating his powers to Prince Baudouin, Duke of Brabant.[113]

- 11 August: Prince Baudouin takes the constitutional oath and for the first time and becomes the Prince Royal.[113]

- 1951

- 13 March: The Cercle artistique et littéraire de Bruxelles is integrated into the Cercle royal Gaulois to become the Cercle royal Gaulois artistique et littéraire.

- 17 July: King Baudouin takes the constitutional oath for the second time at the Palace of the Nation, and becomes the King of the Belgians.[113][114]

- 1952 – The North–South connection is completed; Brussels-Central railway station and Brussels-South railway station open.

- 1953

- 17 June: Transports Intercommunaux de Bruxelles is formed, replacing Les Tramways Bruxellois as the city's main public transport operator.

- 1 August: The Brussels Heliport commences operations under Sabena.

- 15–19 August: The 7th Summer Deaflympics are held in the city.

- 1955 – 25 May: The Royal Flemish Theatre suffers extensive damage from a fire.[115]

- 1956

- The Atomium starts construction.

- 14 February: Lucien Cooremans is appointed mayor by royal decree.

- 1957 – Delhaize inaugurates the first supermarket on the European continent at the Place Eugène Flagey/Eugène Flageyplein.[116]

- 1958

- The city becomes one of the seats of the European Community.

- The Pro-Cathedral of the Holy Trinity is consecrated.

- 17 April–19 October: Expo 58 world's fair is held.

- September – The European School, Brussels I (ESB1) opens.

- 1959 – The State Administrative Centre begins construction.[3]

- 1960

- The city hosts the Congolese Round Table Conference.

- Ballet of the 20th Century contemporary dance company is established.

- 1 November: The city becomes the seat of the Secretariat-General of the Benelux.[117]

- 15 December: The wedding of King Baudouin and Fabiola de Mora y Aragón takes place.

- 1961

- The Serment royal des Saints-Michel-et-Gudule ou des Escrimeurs de Bruxelles is reestablished as La Maison de l'Escrime by Charles Debeur.

- 15 February: Sabena Flight 548 crashes on approach to Brussels Airport, killing all 72 people on board and one person on the ground.[3]

- 27 February: The Royal Association of the Descendants of the Lineages of Brussels is established.

- 21 December: The Film Museum is founded.

- 1962

- The Royal Institute for Theatre, Cinema and Sound (RITCS) is established.

- The Vicariate of Brussels is established.

- 1963 – 2 August: The city becomes part of the bilingual Brussels-Capital administrative area.[118]

- 1965 – The Maison du Peuple/Volkshuis is demolished and is replaced with the Sablon Tower.[3]

- 1966 – 1 November: The Brussels Heliport ceases operations.

- 1967

- The South Tower is built.

- 17 February: The Manhattan Plan, is approved by Prime Minister Paul Vanden Boeynants, paving the way for the construction of the Northern Quarter.

- 1 May: The European Commission starts moving into the Berlaymont.

- 22 May: The À L'Innovation department store is destroyed by fire.[3]

- 16 October: NATO's headquarters are established in the city.

- 13 December: The Study and Documentation Centre for War and Contemporary Society (Cegesoma) is established.

- 1968

- 9 January: Tram line 19 begins service.

- 19 April: Tram line 44 begins service.

- 16 April: Tram line 39 begins service.

- May: Student demonstrations take place at the Free University.[3]

- 6 July: Tram line 55 begins service.

- September: Jan-van-Ruusbroeckollege opens in Laeken.[119]

- 1969

- The Brussels Hilton opens.

- 8 September: The El Al airline offices are bombed.

- 1 October: The Free University splits along linguistic lines into the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB) and Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB).

- 1970

- 12 September: Jacques Georgin is attacked by members of the Order of Flemish Militants while pasting election posters in Laeken and later dies of a heart attack.

- 8 October: Forest National/Vorst Nationaal opens.

- 1971

- The Flower carpet begins at the Grand-Place.

- 7 May: The Bulletin initiates a petition calling for a car-free Grand-Place, signed by many locals, including Jacques Brel, followed by a picnic protest, blocking car access to the square. Months later, the mayor yields.[120]

- 26 July: The Brussels Agglomeration is created.[121]

- 1 September: Mayor Roger Nols of Schaerbeek sets up separate counters in the Town Hall, violating the Language Law on Administrative Affairs requiring bilingual municipal officials.

- 25 November: The first and only elections of the Brussels Agglomeration Council are held.[3]

- 1972 – La Villa Lorraine becomes the first restaurant outside France to earn a Michelin star.

- 1974

- The first Brussels Independent Film Festival is held.

- January: The first Brussels International Film Festival is held.

- 1975

- The Université catholique de Louvain's Jardin des plantes médicinales Paul Moens is established.

- Trademart Brussels is established.

- March: Bruneau restaurant is opened by the chef Jean-Pierre Bruneau.

- 14 May: Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles is released by Chantal Akerman during the 28th Cannes Film Festival.

- 26 April: The first Congress of Brussels Flemings takes place to prepare for the creation of the Brussels-Capital Region.[122]

- 30 July: Bank Brussels Lambert is established.

- 30 August: Pierre Van Halteren is elected mayor.

- 1976

- 20 September: The Brussels Metro begins operating.

- 28 September: The Brussels Planetarium opens.

- 1977 – The first Memorial Van Damme is organised by a group of journalists in honour of Ivo Van Damme in the Heysel Stadium.

- 1978

- The Brussels Ring is constructed.

- The RTBF Symphony Orchestra is formed.[123]

- The Oriental Pavilion is transformed into the Great Mosque of Brussels.

- 1979

- The Archives of the City of Brussels moves into the former Magasins Waucquez.[124]

- The city celebrates the 1,000th anniversary of its founding.[3]

- Au Stekerlapatte restaurant is established by the Flemish radio and television presenter Daniël Van Avermaet.

- 28 August: The Brussels bombing occurs, injuring 18.

1980–2000

[edit]- 1980

- Population of the Brussels-Capital Region: 1,008,715.[125]

- The Flemish Community and the French Community of Belgium each designate Brussels as their capital city.

- 4 December: A French-Algerian man is killed by members of the Front de la Jeunesse, sparking a massive anti-racist demonstration; Justice Minister Philippe Moureaux introduces a law against racism in Parliament, which is adopted a few months later.[126]

- 1981

- 21 March: King Baudouin Park is laid out.[3]

- 1 April: Studio Brussel is established as a regional radio station of the BRT.

- 1 July: Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) representative Naïm Khader is assassinated in the early hours in front of his home in Ixelles.

- 18 July: Lawyer and diplomat Fernand Spaak is shot dead in his flat with a hunting rifle by his estranged wife, Anna-Maria Farina.

- 4 December: The Wittockiana is founded by Michel Wittock.

- 31 December: A burglary by the Brabant Killers at the Gendarmerie barracks in Etterbeek stealing weapons, ammunition, and a car, some of which were allegedly found later in Madani Bouhouche's garage.

- 1982 – The Brussels Urban Transport Museum is established.

- 1983

- First Brussels International Festival of Fantastic Film (BIFF) is held.

- 9 January: Robbery and murder of Greek-born taxi driver Constantin Angelou by the Brabant Killers. The car and body are later found in Mons.[127][128]

- 28 January: Raymond Dewee's Peugeot 504, along with his ID and driving licence, are stolen at gunpoint in Watermael-Boitsfort. Two weeks later, the car is used in an armed robbery at a Genval Delhaize, linked to the Brabant Killers.[129]

- 25 February: The Brabant Killers carry out an armed robbery at a Delhaize in Fort Jaco, stealing less than 600,000 BEF with no fatalities.[130]

- 4 March: Hervé Brouhon is elected mayor.

- 17 May: La Fonderie, Brussels Museum of Industry and Labour, is established.

- 14 July: Turkish administrative attaché Dursun Aksoy is assassinated near his home on Avenue Franklin Roosevelt/Franklin Rooseveltlaan.

- 23 October: The Peace March occurs, with over 400,000 participants, protesting the NATO plan to place nuclear weapons at Kleine-Brogel and Florennes under the Double-Track Decision.

- 1984

- 13 February: The body of Christine Van Hees is discovered in an abandoned mushroom farm in Auderghem.

- 7 September: The Bar Association of Brussels is split into French-speaking and Dutch-speaking orders.[131]

- 2–8 October: The Cellules Communistes Combattantes (CCC) carry out three attacks against companies cooperating with NATO, resulting in minimal damage.[132]

- 15 October: Attack on the liberal Paul Hymans Institute in Ixelles by the CCC.[132]

- 1985

- 15 January: The CCC attacks a NATO/SHAPE support group in Woluwe-Saint-Lambert.[132]

- 1 May: The CCC attacks the Federation of Belgian Enterprises offices on the Rue des Sols/Stuiversstraat, killing two firefighters and injuring 13 others.[132]

- 6 May: The CCC carries out an attack against a Gendarmerie building, blaming them for the death of the two firefighters on 1 May.[132]

- 16 May: Pope John Paul II visits the city.[133]

- 29 May: The Heysel Stadium disaster takes place.[133]

- 8 October: The CCC attacks the headquarters of electricity producer Intercom.[133]

- 4 November: The CCC attacks the bank BBL in Etterbeek.[133]

- 21 November: During Ronald Reagan's visit to NATO headquarters in Evere, a bomb explodes in an office building targeting Motorola for its cooperation with the military.[132]

- 14 December: The French-language television station Télé Bruxelles is established.

- 1986

- 29 September: Autoworld opens.

- 8 December: The Flemish private club De Warande is founded and establishes itself in the Hôtel Empain.

- 1987

- Jeanneke Pis statue is erected as counterpoint to Manneken Pis.

- 9 May: The 32nd edition of the Eurovision Song Contest is held at Brussels Expo.

- 1988

- 2 October: Metro line 2 begins service.

- November: Kinepolis Brussels opens.

- 1989

- 9 March: The Jewish Museum of Belgium opens.

- 29 March: Saudi Arabian Imam Abdullah al-Ahdal is fatally shot at the Great Mosque of Brussels by members of the Lebanese Soldiers of the Right.

- 12 June: Mini-Europe opens.

- 18 June: The Brussels-Capital Region is formed; the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region is established.[134]

- 12 July: Charles Picqué becomes the first Minister-President of the Brussels-Capital Region.

- 14 July: The Flemish, French and Common Community Commissions are established.[135]

- 6 October: The Belgian Comic Strip Center opens.

- 1990

- Population of the Brussels-Capital Region: 964,385.[125]

- The first Couleur Café is held.

- 25 February: Kosovar human rights activist Enver Hadri is assassinated by three Yugoslavs working for the State Security Administration.

- 22 March: Canadian engineer Gerald Bull is assassinated by Mossad outside his apartment in Uccle.

- 26 October: The first Le Pain Quotidien bakery is established on the Rue Antoine Dansaert/Antoine Dansaertstraat by Alain Coumont.

- 23 December: The Brussels Intercommunal Transport Company is formed by the Government of the Brussels-Capital Region, replacing Transports Intercommunaux de Bruxelles.

- 1991

- The first comic strip murals is created on the Rue du Marché au Charbon/Kolenmarkt.

- 5 March: The Brussels-Capital Region adopts its first flag.

- 10–12 May: Riots erupt in Forest in response to police violence, leading to the arrest of 273 people.

- 12 December: The Jeugdtheater Brussel is established after uncertainty regarding youth theatre within the Beursschouwburg.

- 1992

- 27 March: Riots erupt in Cureghem/Kuregem.

- 5 August: Loubna Benaïssa is killed on her way to the supermarket by Patrick Derochette.

- 1993

- The Espace Léopold opens.

- The first Brussels International Festival of Eroticism is held.

- 20 January: The kidnapping of Ulrika Bidegård takes place.

- 20 July: Michel Demaret is appointed mayor by the City Council.

- 7 August: The funeral of King Baudouin takes place.

- 9 August: King Albert II takes the constitutional oath at the Palace of the Nation.

- 15 September: The Dutch-language television station TV Brussel is launched from the Royal Flemish Theatre.[136]; Beliris is established as a joint venture between the Belgian Federal Government and the Brussels-Capital Region.

- 7 October: An ordinance is adopted to establish a framework for enhancing vulnerable neighbourhoods, later referred to as "neighbourhood contracts".[2][4]

- 4 December: Tram line 82 begins service.

- 1994

- The City of Brussels is designated capital of Belgium and seat of the Federal Government.[137]

- 1 April: The first Kunstenfestivaldesarts is held.

- 28 April: Freddy Thielemans is elected mayor for the first time.[138]

- 16 April: The Fuse nightclub opens.

- May: The Kunstenfestivaldesarts (KFDA) begins.

- 30 June: The Performing Arts Research and Training Studios (P.A.R.T.S.) contemporary dance school is established by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and Bernard Foccroulle.[139]

- 14 November: The international terminal of Brussels-South railway station opens.

- 1995

- The Erasmus Brussels University of Applied Sciences and Arts (EhB) is established.

- 1 January: The Province of Brabant is split into Flemish Brabant and Walloon Brabant; The Governor of the Administrative Arrondissement Brussels-Capital is established.

- 5 April: Riots erupt in Molenbeek; several gendarmes and a TV Brussel cameraman are injured.

- 5 May: The Belgian Pride is established.

- 21 May: François-Xavier de Donnea is appointed mayor by the City Council.

- 1996

- The South Tower is renovated.

- 20 October: The White March takes place as a protest against the mishandling of the Dutroux affair.[140]

- 1997 – 7 November: Riots erupt in Cureghem after police shot and killed Saïd Charki in his car.

- 1998

- The Musical Instruments Museum (MIM) relocates to the Hôtel de Spangen and the former Old England department store.

- The first Brussels Short Film Festival is held.

- 5 March: The Cercle de Lorraine business club is founded at the Château Fond'Roy.

- 26 December: A fire breaks out in the Royal Park Theatre.[60]

- 17 November: Anti-Kurdish violence erupt, as around 300 Turkish youths targeted the Kurdish community of Saint-Josse-ten-Noode, setting fires at three associations and attacking several families.

- 2 December The Grand-Place is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[3][141]

- 1999

- Het Zinneke statue is erected by analogy with Manneken and Jeanneke Pis.

- 5 June: The René Magritte Museum opens.

- 15 July: Jacques Simonet becomes Minister-President of the Brussels-Capital Region.

- 8 September: The Clockarium is established.

- 4 December: The wedding of Prince Philippe and Mathilde d'Udekem d'Acoz takes place.

- 2000

- The city is named European Capital of Culture alongside eight other European cities.[142]

- The Hôtel Tassel, Hôtel Solvay, Hôtel van Eetvelde and Maison & Atelier Horta are listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

- 27 May: The first Zinneke Parade is held.

- 28 July: The city is divided into five police zones.[143][144][145][146][147]

- 18 October: François-Xavier de Donnea becomes Minister-President.

21st century

[edit]- 2001

- Tour & Taxis begins redevelopment.

- 16 January: Freddy Thielemans is elected mayor for the second time.

- 28 April: Police Zone: Brussels - Ixelles is formed as the sixth police zone in the city.[148]

- 13 July: The Lambermont Accord is signed, increasing the representation of Dutch speakers in Parliament.

- 25 October: Princess Elisabeth, Duchess of Brabant is born at Erasmus Hospital.

- 2002

- 7 May: Ahmed Isnasni and Habiba El-Hajji are shot and killed by their neighbour, Hendrik Vyt, at their residence in Schaerbeek. Vyt also wounds two of their sons before committing self-immolation.[149][150]

- 10 December: The Film Museum in integrated into CINEMATEK.

- 2003

- 13 March: The Iris Festival is created by ordinance.[151]

- 6 June: Daniel Ducarme becomes Minister-President.

- 26 June: Brasserie de la Senne is established.

- 20 September: The Wittockiana opens to the public.

- 2004

- The North Galaxy Towers are built.

- 18 February: Jacques Simonet becomes Minister-President for the second time.

- 14–17 April: The BRussells Tribunal is held as part of the World Tribunal on Iraq.

- 2005

- the first Be Film Festival is held.

- 19 July: The BELvue Museum opens in the Hôtel Belle-Vue; Charles Picqué becomes Minister-President for the second time.

- 2006

- The Atomium is renovated.[152]

- 6 March: Tram line 24 begins service.

- 12 April: Joe Van Holsbeeck is fatally stabbed at Brussels-Central railway station in an attempted robbery of his MP3 player.

- 29 August: Benjamin Rawitz-Castel is murdered during a robbery by Junior Kabunda.

- 17 September: The Cyclocity bicycle-sharing system is launched in the Pentagon.[153]

- 23–29 September: Riots break out in the Marolles after Fayçal Chaaban is found dead in his cell.

- 2007

- The Hogeschool-Universiteit Brussel (HUB) is established.[154]

- 25 March: Brussels Airlines is formed.

- 25 May: The WIELS contemporary art centre opens in the former Wielemans-Ceuppens brewery.

- 2 July: Tram line 4 begins service.

- 28 September: The Manga murder occurs.

- 2008

- Denis-Adrien Debouvrie, a wealthy local restaurant owner and creator of Jeanneke Pis, is stabbed and killed by the Tunisian restaurant owner Tarek Ladhari.[155]

- The first Brussels Gallery Weekend is held.[156]

- The first Offscreen Film Festival is held.

- 30 June: Tram lines 3 and 51 commence service.

- 2009

- The Stoclet Palace is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- 4 April: Reorganisation of the Metro resulted in the creation of lines 1, 5, and 6.

- 16 May: Cyclocity is rebranded to Villo! and expanded to the whole region.

- 2 June: The Magritte Museum opens.

- 17 November: Olivier Bastin is appointed the first Architect of the Brussels-Capital Region.[157]

- 12 December: The funeral of Queen Fabiola takes place.

- 2010

- Population of the Brussels-Capital Region: 1,089,538.[125]

- 24 November: The Cercle de Lorraine is reestablished at the Hôtel de Mérode-Westerloo.[158]

- 26–29 November: The European Assembly for Climate Justice is held.

- 2011 – 14 March: Tram line 7 begins operations, replacing the routes previously covered by lines lines 23 and 24.

- 2012

- 13 March: Muslim scholar Abdullah al-Dahdouh is murdered in an unprovoked attack in the Islamic Center of Imam Reza.

- 10 June: The first Picnic the Streets occurs.

- 2013

- 7 May: Rudi Vervoort becomes Minister-President of the Brussels-Capital Region.

- 21 July: King Philippe takes the constitutional oath at the Palace of the Nation.

- 6 December: The Fin-de-Siècle Museum opens.

- 13 December: Yvan Mayeur is elected mayor.

- 2014

- 1 January: Odisee is established.

- 10 March: Vlaams-Brusselse Media forms.

- 23 May: Choco-Story Brussels is established.

- 24 May: The Jewish Museum of Belgium shooting occurs, killing 4.

- 18 June: The .brussels generic top-level domain is added to the DNS root zone.

- 1 July: The Governor of the Administrative Arrondissement Brussels-Capital is replaced with the Senior Official of the Administrative Arrondissement Brussels-Capital.[159]

- 2015

- 9 January: The Brussels-Capital Region adopts a new flag.

- 25 September: Train World opens in Schaerbeek railway station.

- 21–25 November: The Brussels lockdown occurs, the Federal Government imposes a security lockdown, due to information about potential terrorist attacks in the wake of the November 2015 Paris attacks by Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant on 13 November.

- 11 December: Design Museum Brussels opens.

- 13 December: The Brussels S Train begins operating.[160]

- 2016

- 7–11 January: The Call Brussels initiative occurs, promoting the city after the November 2015 Paris attacks and subsequent lockdown of the city.

- 8 March: The CIVA architectural centre is established.

- 15–18 March: Police raids are conducted in connection to the attacks in Paris four months earlier.

- 22 March: The Brussels bombings occur, killing 34 and injuring 230.[161][162][163][164]

- 4 April: The Schuman-Josaphat tunnel opens.

- 5 October: The Brussels stabbing attacks occur, 4 injured including the suspect.

- 2017

- Parts of the Sonian Forest becomes part of the transnational 'Ancient and Primeval Beech Forests of the Carpathians and Other Regions of Europe' UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- 6 May: The House of European History (HEH) opens.

- 25 May: NATO's new headquarters open.[165]

- 9 June: Philippe Close is appointed mayor by the Government of the Brussels-Capital Region.[166]

- 20 June: The Brussels-Central bombing occurs, the perpetrator is killed.

- 25 August: The Brussels stabbing attack occurs, the perpetrator is killed and 2 injured.

- 7 December: 45,000 people gather in the city for Wake Up Europe! in support of Catalan independence.

- 2018

- 5 May: KANAL - Centre Pompidou opens in the former Citroën Garage.

- 12 May: Manneken Pis receives his 1000th costume, created by fashion designer Jean-Paul Lespagnard.[167][168]

- 5 June: Nigerian sex worker Eunice Osayande is fatally stabbed by a client. Her death leads to protests by migrant sex worker communities.[169]

- 20 June: The reastablised Brussels International Film Festival is held.

- 2 December: The first School Strike for Climate occurs in the city, drawing 65,000 people to the streets, demanding clean air, renewable energy, and political action.[170]

- 30 September: Océade closes to make way for NEO.

- 20 November: The Brussels stabbing attack occurs, injuring 2 including the perpetrator.

- 2019

- 26 May: Brussels regional elections are held.

- 6 July: The 2019 Tour de France starts in the city.

- 12 October: The MigratieMuseumMigration opens.

- 14 December: Wolf Sharing Food Market opens in the former ASLK/CGER counter room, becoming the city's first food market.

- 2020

- 2 February: The first recorded case of COVID-19 in Belgium after nine Belgian nationals living in Hubei are repatriated.

- 11 March: The first COVID-19 related death in Belgium is confirmed of a 90-year-old female patient who was being treated in Etterbeek.[171]

- 18 March: The city joins the rest of Belgium in a nationwide lockdown that lasts until 8 June in an attempt to reduce the number of cases.

- 7 June: About 10,000 protesters gather as part of the George Floyd protests in Belgium.[172][173]

- 2021

- 14 January: Riots erupt following the death of Ibrahima Barrie in police custody.

- 10 October: The Back to the Climate protest occurs on the eve of COP26, with police reporting 25,000 participants and organizers claiming 50,000 to 70,000.

- 2022

- 24 January: More than 50,000 people protest against COVID-19 rules.

- 30 September: Haren Prison opens.

- 4 October: The Suzan Daniel Bridge opens over the Brussels–Scheldt Maritime Canal.

- 10 November: The Brussels stabbing occurs, killing 1 and 2 injured including the perpetrator.

- 2023

- 14 September: The Université Saint-Louis – Bruxelles becomes part of Université catholique de Louvain.[174]

- 16 October: The Brussels shooting occurs, killing 3 including the perpetrator and injuring 1.

- 2024

- 1 February: The Monument to John Cockerill is vandalised during a farmers' protest in front of the European Parliament.[175]

- 9 June: Brussels regional elections are held.

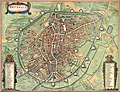

Evolution of the Brussels map

[edit]16th century

[edit]- 1555

- 1567

17th century

[edit]- 1610

- ~1657

18th century

[edit]- ~1700

- ~1711

- 1740

- ~1745

- 1777

19th century

[edit]- 1830

- 1837

- 1843

- 1876

- 1894

20th century

[edit]- 1900

- 1907

See also

[edit]- History of Brussels

- List of mayors of the City of Brussels (largest municipality in the Brussels-Capital Region)

- List of municipalities of the Brussels-Capital Region

- Timeline of Belgian history

- Timelines of other municipalities in Belgium: Antwerp, Bruges, Ghent, Leuven, Liège

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "INLEIDING TOT DE GESCHIEDENIS VAN UKIŒL" (PDF). Ucclensia (14): 22. 14 March 1968.

- ^ a b "Microsoft Word - resume_poster_Prignon.doc". archive.wikiwix.com. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd State, Paul F. (2004). Woronoff, Jon (ed.). Historical Dictionary of Brussels (PDF). United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 0-8108-5075-3.

- ^ a b "De Frankische tijd". www.delbeccha.be. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ "Archeologische site in Laarbeekbos krijgt infoborden". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ State, Paul F. (2004). Historical Dictionary of Brussels. Scarecrow Press. p. 269.

- ^ "CatholicSaints.Info » Blog Archive » Weninger's Lives of the Saints – Saint Guido, Confessor". Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ De Sancto Verono Lembecae et Montibus Hannoniae.

- ^ "Verloren verleden: De Brusselse lepralijders". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ Hennaut, Eric; Hulsbosh, Laurent. De Grote Markt van Brussel. Solibel Edition.

- ^ "Ancien Grand Serment Royal et Noble des Arbalétriers de Notre Dame du Sablon". Erfgoedcel Brussel (in Dutch). Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ Charles Harrison Townsend (1916), Beautiful buildings in France & Belgium, New York: Hubbell, OL 7213871M

- ^ "De keure van 1229", Brussel: Waar is de Tijd, 6 (1999), pp. 133-135.

- ^ "Begijnhof – Inventaris van het bouwkundig erfgoed". monument.heritage.brussels (in Dutch). Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ a b Grant Allen (1904), Belgium: its cities, Boston: Page, OL 24136954M

- ^ "Histoire". www.meyboom.be. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ NWS, VRT (22 January 2020). "Waarom een monnik het hoofd van "de eerste feministe" van Brussel verplettert in de kathedraal". vrtnws.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ a b c Vannieuwenhuyze, Bram. "Brussel in vuur en vlam. Feiten, preventie, bestrijding en verwerking van historische stadsbranden" (PDF). Tijd-Sc (2): 20.

- ^ "L'Ommegang". patrimoine.brussels (in French). Direction du Patrimoine culturel.

- ^ Cluse, C.M. "DE JODENVERVOLGINGEN TEN TIJDE VAN DE PEST (1349-50) IN DE ZUIDELIJKE NEDERLANDEN" (PDF).

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Verloren verleden: Het begraven van de doden". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Un peu d'histoire". GSR BXL (in French). Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ David M. Nicholas, The Later Medieval City: 1300–1500 (Routledge, 2014), p. 139.

- ^ "Verloren verleden: De Brusselse vroedvrouwen". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Verloren verleden: De Brusselse dominicanen". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ Robert Proctor (1898). "Books Printed From Types: Belgium: Bruxelles". Index to the Early Printed Books in the British Museum. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner and Company. hdl:2027/uc1.c3450632 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ a b BBC News (29 February 2012). "Belgium Profile: Timeline". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ DBNL. "De Corenbloem, Repertorium van rederijkerskamers in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden en Luik 1400-1650, Anne-Laure Van Bruaene". DBNL (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ "De Wapengilden van Brussel — Patrimoine - Erfgoed". erfgoed.brussels. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ DBNL. "De Lelie, Repertorium van rederijkerskamers in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden en Luik 1400-1650, Anne-Laure Van Bruaene". DBNL (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ DBNL. "De Violette, Repertorium van rederijkerskamers in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden en Luik 1400-1650, Anne-Laure Van Bruaene". DBNL (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ DBNL. "DBNL rederijkerskamer - Het Mariacransken". DBNL (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ Hennaut 2000, p. 17.

- ^ N., R. (1932). "Bonenfant (Paul). — La création à Bruxelles de la Suprême Charité. Annexe au Rapport annuel de la Commission d'Assistance publique de la ville de Bruxelles pour 1928,1930". Revue du Nord. 18 (71): 231–231.

- ^ Strickland, Agnes (1903). Lives of the queens of England, from the Norman conquest;. unknown library. Philadelphia, Printed for subscribers by G. Barrie & son.

- ^ "Tijdsbalk - 1560 tot 1570 jaar in onze jaartelling" (in Dutch). willebroek.be. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ Jamieson, Frances (formerly Thurtle) (1820). The History of Spain, from the Earliest Ages ... to the Return of Ferdinand VII. in 1814. Whittaker.

- ^ Vanden Bossche, Hugo. "Deel 4: Begijnhofkerk Sint-Jan-de-Doper" (PDF). Begijnhofkrant (49).

- ^ van Stipriaan, René (2021). De zwijger. Het leven van Willem van Oranje. p. 610.

- ^ "Farnese, Alessandro", in Historical Dictionary of Brussels, by Paul F. State (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015 p.163

- ^ Demetrius C. Boulger, The History of Belgium: Cæsar to Waterloo (Princeton University Press, 1902) p.335

- ^ "Verloren verleden: Broeders van het Gemene Leven". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Verloren verleden: De Brusselse augustijnen". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Verloren verleden: Waanzin in het Simpelhuys". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Anonymous, German, 16th century | Entrance of the Archduke Ernest to Brussels, January 30, 1594". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ De Schrijver, Machteld. Een voorouder van Ludwig Van Beethoven als heks verbrand (PDF) (in Dutch).

- ^ "Verloren verleden: Dwangarbeid in het Deuchthuys". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Verloren verleden: Dwangarbeid in het Deuchthuys". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Groot Broederschap van de Heilige Sint-Guido stelt zichzelf tentoon". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ "De Swaene | broederschap-van-sint-guido-2023". De Swaene (in Flemish). Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Commune de Ganshoren". ArchivIris (in French). 17 June 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Sleiderink, Remco; Geysen, Frederik. "UITZONDERLIJKE ONTHULLING VAN HET OUDSTE ARCHIEFSTUK IN HET AMVB" (PDF). Arduin (15).

- ^ a b c "Verloren verleden: De pest in Brussel". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ De Roose, Fabien (1999). De Fonteinen van Brussel [The Fountains of Brussels] (in Dutch). Brussels. ISBN 978-90-209-3838-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Henne & Wauters 1845.

- ^ "Chambre de Commerce et d'Industrie de Bruxelles". search.arch.be. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ DBNL. "Tsaar Peter de Grote: identiteit en imago Rietje van Vliet, Literatuur. Jaargang 13". DBNL (in Dutch). Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ "KMI - 16de - 18de eeuw - Ancien Régime". KMI (in Dutch). Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ James E. McClellan (1985). "Official Scientific Societies: 1600-1793". Science Reorganized: Scientific Societies in the Eighteenth Century. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-05996-1.

- ^ a b "L'histoire du Parc". Théâtre Royal du Parc. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ "Politieke spanningen tijdens Brabantse Omwenteling". Historiek (in Dutch). 4 December 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ A. Graffart, "Register van het schilders-, goudslagers- en glazenmakersambacht van Brussel, 1707–1794", tr. M. Erkens, in Doorheen de nationale geschiedenis (State Archives in Belgium, Brussels, 1980), pp. 270–271.

- ^ Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. "Museum History". Archived from the original on 7 June 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ "BIG CITY. In Argentinië eten ze een Brusselse peersoort". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ "De Rederijkers vierden feest". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Belgium". International Banking Directory. New York: Bankers Publishing Company. 1922. hdl:2027/hvd.hb1sji.

- ^ a b c "Belgium". Statesman's Year-Book. London: Macmillan and Co. 1869. hdl:2027/nyp.33433081590337.

- ^ "Belgium". Political Chronology of Europe. Europa Publications. 2003. ISBN 978-1-135-35687-3.

- ^ "Het project". www.kanaalnaarcharleroi.be. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ "KBR door de eeuwen heen • KBR". KBR (in Dutch). Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ "Cercle Royal du Parc – Histoire". Cercle Royal du Parc (in French). Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ "De Belgische Frietkotcultuur · Centrum Agrarische Geschiedenis (CAG)". cagnet.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ a b Chambers 1901.

- ^ "Recherche". Le Soir (in French). Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ Spapens 2005, p. 19.

- ^ "De Commune van Parijs en Brussel". Historiek (in Dutch). 10 January 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2024.