Tunnels of Claudius

Cunicoli di Claudio | |

Entrances to the "major" tunnel | |

| Location | Avezzano, Capistrello, Province of L'Aquila, Abruzzo, Italy |

|---|---|

| Region | Marsica |

| Coordinates | 41°59′18.7″N 13°26′0.2″E / 41.988528°N 13.433389°E |

| History | |

| Cultures | Ancient Rome |

| Site notes | |

| Management | Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici dell'Abruzzo |

| Website | cultura.regione.abruzzo.it (in Italian) |

The Tunnels of Claudius (Italian: Cunicoli di Claudio) consist principally of a 6 km-long tunnel (or emissary) together with several monumental service tunnels which Roman Emperor Claudius had built by 52 AD[1] to partially drain the Fucine Lake in Abruzzo, protecting riparian villages from floods and creating agricultural land. It was a massive engineering project involving 30,000 workmen and slaves who completed it in just 11 years, and considered among the grandest in antiquity.[2] It was the longest tunnel ever built until the inauguration of the Fréjus Rail Tunnel in 1871.[3]

The lake water flowed under Mount Salviano and emptied into the Liri River beneath the present town of Capistrello.

Without regular maintenance the emissary often became clogged, and the lake returned to its original size with regular flooding.[4] It was only in 1854 when Alessandro Torlonia renovated the tunnels mostly following the Roman ones[5] that knowledge of the Roman tunnel was increased whilst also causing the destruction of its superficial features. Original Roman features can be seen in opus reticulatum in the entrance and exit areas.

In 1902 the "Tunnels of Claudius" (including the many service tunnels) were included among Italian national monuments;[6] the tunnel area represents a site of archaeological and speleological interest, provided with a park inaugurated in 1977 with the purpose of protecting and exploiting the whole system.[7][8]

History

[edit]Lake Fucino was once the 3rd largest lake in Italy and the area is a basin completely enclosed by mountains and with no natural outlet. It is fed by snow meltwater and the seasonal ancient water level variation is estimated to be typically 12 m.

Planning

[edit]

The Marsi, the local inhabitants, had made petitions to Rome to control the unstable level of the lake which very often flooded villages because of the frequent cloggings of the only natural swallow-hole at Petogna near Luco dei Marsi. In summer because of the receding waters, the lands surrounding the inhabited areas often became marshy causing serious health problems due to malaria.[9]

The first plan to drain the lake was of Julius Caesar (r. 49-44 BC) but he died before it could be advanced.[7]

In 41 AD[1] Emperor Claudius resumed the ambitious plan and, thanks to substantial public financing, entrusted a Roman enterprise with the works. The easiest plan was to dig the shortest tunnel through the low Cesolino hill and into the Salto River and eventually into the Tiber. This was discarded because it would be a flood threat to Rome. The second, more difficult, plan was therefore adopted with a longer, deeper tunnel to lead the water into the Liri River [7]

The aim was to only regulate the water level and not drain the lake completely. The tunnel had to be designed to be the shortest compatible with a very shallow slope and in a compass direction that ensured it entered the Liri river at a level lower than the lake, a remarkable feat considering the instruments of the time. Once the direction was decided, the required inclination then determined the location of the tunnel ends.

The emissary has a variable cross-section of 5 to 10 m2 (54 to 108 sq ft), an average flow rate of 9.1 m3/s (320 cu ft/s)[1] and an average gradient of 1.5 m/km (7.9 ft/mi).[10][11]

Construction

[edit]

The system consisted of three main parts:[12]

- The incile: the canal for collecting the water in a set of tanks and dam

- The main tunnel

- The cunicola: the secondary service tunnels and wells.

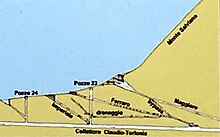

The system of vertical wells with a square section and the inclined tunnels increased the number of places where the main tunnel could be excavated to speed up construction. They also provided air and ventilation as well as allowing removal of waste and water during construction. Where the rock was weak the tunnels had to be supported with scaffolding and remains of this was found in Torlonia's renovation.[13] Once a well was dug to the appropriate depth, tunnel excavation started proceeding in opposite directions. At least 40 wells were dug, 29 of which are on the west side of the mount Salviano and 11 on the east slope. The depth of the wells varies from 19 m to 122 m (number 22) while those on the western side are generally greater than 80 m.

The depth of the wells was determined through the use of a surveying technique known as cultellatio consisting of mapping and finding the level of the land in places along the route by means of a series of horizontal and vertical steps. The sum of the vertical and horizontal measurements made possible the calculation of levels and distances. A vertical well was then dug to a required depth relative to the water intake. Subsequently, other vertical wells were dug along the route using the same technique.

The long section under Mount Salviano where wells could not be dug was the most difficult and went through loose rock and pebbles making a deviation necessary.

Accidents during the construction included several landslides in the most vulnerable and sandiest sections and in the dam between the mouth of the tunnel near the Fucine inlet.[14]

Completion

[edit]When the works were concluded Claudius, before the opening of the locks, celebrated the work by organising a great naumachia, a naval battle with warships on the lake with 19000 combatants made up of gladiators and criminals, with the presence of his wife Agrippina and the young Nero.[15] Crowds of spectators came from all over Italy to see the show.

It was soon discovered that the emissary was not deep enough so the outlet was dammed and the tunnel excavated further. On completion Claudius held a second gladiatorial battle on the lake on a huge stage of pontoons.

The lake shrank by about 6,000 hectares (15,000 acres) and warded off the flood danger. The economy of Marsica and especially of the cities of Alba Fucens, Lucus Angitiae and Marruvium thrived and the surrounding mountainous areas became popular as holiday resorts.[16]

Later under Trajan, between 98 and 117 AD, and Hadrian, between 117 and 138 AD clearance of blockages and repairs became necessary.

Neglect

[edit]The tunnel was soon neglected by Nero (r.54-68)[17] and became blocked, but was re-opened by Hadrian.[18] It was blocked again before 235.[19]

With the fall of the Roman Empire and the Barbarian invasions maintenance inevitably failed and also because of a serious earthquake in 508 AD,[20] the canal was clogged with the consequent return of the Fucine Lake to its previous levels.[21] In the subsequent centuries Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (13th century) and Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies (1790) tried to restore the water drainage into the Roman emissary, failing due to the scarcity of funds and the complexity of the project.[22] In 1854 Torlonia finally renovated the tunnel mostly following that of Claudius.

Recent Restoration

[edit]In June 1977, with the aim of protecting and exploiting the work, the Archaeological Park of Claudius was established, between the entrances to the tunnels and the Fucine Inlet.[8][23]

The work was included among the Luoghi del Cuore ("Places of the Heart") for the year 2016 by FAI.[24]

The tunnels

[edit]The most impressive service tunnels were on the eastern side:

- Major Tunnel (Italian: Cunicolo Maggiore), located on the eastern side of the mountain, is the most monumental and features three large arches for entrances which join together after a short inner stretch. It gave access to the deepest section under the mountain. Inside is the oblique tunnel (the so-called bypass).

- Blacksmith Tunnel (Italian: Cunicolo del Ferraro), on the eastern side of the mountain. The first stretch was paved and equipped with lighting. The bypass connects it with the Major tunnel.

- Imperial Tunnel (Italian: Cunicolo Imperiale), located lower than the previous one, connected to it through well no. 23.

- Coppersmith, Machine and Oil-Lamp Tunnels (Italian: Cunicoli del Calderaro, della Macchina e della Lucerna), on the western side of the mountain.[25][26][27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Campanelli 2001, p. 9

- ^ Suetonius, The Life of Claudius, 20

- ^ Maidl, Bernhard (2018). Faszination Tunnelbau : Geschichte und Geschichten. Berlin: Ernst und Sohn. ISBN 978-3-433-03113-1.

- ^ Reitz-Joosse, Bettina, 'Debating the Draining of the Fucine Lake', Building in Words: Representations of the Process of Construction in Latin Literature (New York, 2022), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197610688.003.0003

- ^ "Storia del consorzio" (in Italian). Consorzio di bonifica ovest bacino Liri - Garigliano. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Elenco degli edifizi monumentali in Italia". archive.org (in Italian). Ministero della pubblica istruzione. 1902. p. 382. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ a b c Abruzzo Molise. Guida d'Italia (in Italian). Touring Club Italiano. 1997. ISBN 88-365-0017-X.

- ^ a b Burri 2002.

- ^ Palmieri 2006, p. 17.

- ^ Servidio et al. 1977, p. 144.

- ^ Santoriello, Marino. "Il prosciugamento" (in Italian). Terre Marsicane. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ L Di Angelo et al., The 3D virtual reconstruction of an engineering work of the past, 2018 IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 364 012010 doi:10.1088/1757-899X/364/1/012010

- ^ Southern Polytechnic State University ROMAN GROMATICI PRACTICES, http://www.surveyhistory.org/southern_polytechnic_state_university1.htm

- ^ Campanelli 2001, p. 26

- ^ Tacitus Annals, Book XII 56

- ^ Grossi 2002, p. 24.

- ^ Pliny, Natural History 36.24

- ^ Historia_Augusta, Hadrian, 22.12

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History 60, 11

- ^ Campanelli 2001, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Santellocco 2004, p. 88.

- ^ Grossi 2002, pp. 24–25

- ^ "Una nuova sinergia muove la Marsica intorno ai Cunicoli di Claudio" (in Italian). Marsica Live. 22 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ "Emissario di Claudio/Torlonia" (in Italian). Fondo Ambiente Italiano. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ Tudico, Luigi (2009). "Fucino, il prosciugamento del lago" (PDF) (in Italian). Aercalor.altervista.org. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ Servidio et al. 1977, p. 152

- ^ Colarossi, Patrizia (19 September 2015). "Cunicoli di Claudio: l'opera idraulica di età romana" (in Italian). MiBACT. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- Afan de Rivera, Carlo (1836). Progetto della restaurazione dello emissario di Claudio e dello scolo del Fucino (in Italian). Naples: Stamperia e cartiera del Fibreno. SBN IT\ICCU\SBL\0484194.

- Burri, Ezio (2002). Il parco naturalistico archeologico dei cunicoli di Claudio (Avezzano, Italia centrale) (in Italian). Firenze: Associazione Nazionale dei Musei Scientifici (estratto da Museologia scientifica). SBN IT\ICCU\IEI\0325809.

- Campanelli, Adele; et al. (2001). Il tesoro del lago: l'archeologia del Fucino e la Collezione Torlonia (in Italian). Pescara: Carsa edizioni. SBN IT\ICCU\UMC\0099815.

- Grossi, Giuseppe (2002). Marsica: guida storico-archeologica (in Italian). Luco dei Marsi: Aleph. SBN IT\ICCU\RMS\1890083.

- Jetti, Guido (2016). Avezzano e il prosciugamento del Fucino (in Italian). Avezzano: Kirke (repr.). SBN IT\ICCU\RAV\2037877.

- Maria Palanza, Ugo (1990). Avezzano: guida alla storia e alla città moderna (in Italian). Avezzano: Amministrazione comunale. SBN IT\ICCU\AQ1\0060998.

- Palmieri, Eliseo (2006). Avezzano, un secolo di immagini (in Italian). Pescara: Paolo de Siena. SBN IT\ICCU\TER\0011256.

- Santellocco, Attilio Francesco (2004). Marsi: storia e leggenda (in Italian). Luco dei Marsi: Touta Marsa. SBN IT\ICCU\AQ1\0071275.

- Servidio, A.; Radmilli, A. M.; Letta, C.; Messineo, G.; Mincione, G.; Gatto, L.; Vittorini, M.; Astuti, G. (1977). Fucino cento anni: 1877-1977 (in Italian). L'Aquila: Roto-Litografia Abruzzo-Press. SBN IT\ICCU\IEI\0030150.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Tunnels of Claudius at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tunnels of Claudius at Wikimedia Commons

- "Cunicoli di Claudio". regione.abruzzo.it (in Italian). Regione Abruzzo. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2017.