uMgungundlovu

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2010) |

uMgungundlovu was the royal capital of the Zulu King Dingane (1828–1840) and one of several military complexes (amakhanda) which he maintained. He established his royal kraal in 1829 in the eMakhosini valley against Lion hill (Singonyama), just south of the White Umfolozi River.

The name uMgungundlovu stems from the Zulu word or phrase ungungu we ndlovu, which means "the secret conclave of the elephant". Some sources also refer to uMgungundlovu as "the place of the elephant". The word indlovu (elephant) refers to the king of the Zulu people.

Description

[edit]Dingane established his royal kraal, or capital, at uMgungundlovu in 1829. He took power in 1828 after assassinating Shaka, his half-brother. This was one of the king's military complexes (amakhanda) and was located in the eMakhosini valley, just south of the White Umfolozi River on the slope of the Lion hill. It lay between two streams, the Umkhumbane to the south and Nzololo to the north.

Encampment (iKhanda)

[edit]The oval-shaped ikhanda (military settlement) contained between 1,400 and 1,700 huts, which could house between 5,000 and 7,000 residents. This number varied as regiments were called up at different times. The huts stood six to eight deep and formed a huge ring around an open area, known as the large cattle kraal (isibaya esikulu). This space was also utilised for military parades and gatherings. The circle of huts was enclosed both inside and out by a strong defensive palisade.

The main entrance (isango) was on the northern, or lower, side of the slope against which the complex lay. This entrance was divided into two sections to control incoming and outgoing traffic. Narrow entrances at several places in the palisade controlled access to the ikhanda. Inside the arena were smaller cattle enclosures; these were built bordering the inside palisade of the hut circle, and contained the herds.

From the main entrance, which served as a dividing line between the eastern and western sections (uhlangothi), the huts of the warriors stretched round the circle of the royal area (isigodlo). On the eastern side were huts occupied by four selected regiments under the leadership of the chief (induna) Ndlela. On the western side were those under the command of the induna Dambuza. Scattered among these huts were stilted huts used for storage of warriors' shields.

Royal enclosure

[edit]The royal enclosure (isigodlo) was situated behind a palisade fence on the southern, or higher, side of the oval-shaped complex, directly opposite the main entrance. The king, his mistresses and female attendants (Dingane never married officially), a total of at least 500 people, resided here.[1] The women were divided into two groups, namely the black isigodlo and the white isigodlo. The black isigodlo comprised about 100 privileged women, and within that group another elite called the bheje, a smaller number of girls, favoured by the king as his mistresses. A small settlement was built for them behind the main complex where they could enjoy some privacy. The remainder of the king's women were called the white isigodlo. These consisted mainly of girls presented to the king by his important subjects. He also selected other girls at the annual first fruit ceremony (umkhosi).

A large half-moon shaped area was included in the black isigodlo; here the women and the king sang and danced. The huts in the black isigodlo were divided into compartments of about three huts each, enclosed by a two-metre-high hedge of intertwined withes, which created a network of passages.[2]

The king's private hut (ilawu) was located in one such triangular compartment and had three or four entrances.[2] His hut was very large and was kept very neat by attendants; it could easily accommodate 50 people. Modern archaeological excavations have revealed that the floor of this large hut was approximately 10 metres in diameter. Archaeologists found evidence inside the hut of 22 large supporting posts completely covered in glass beads.[3] These had been noted in historical accounts by Piet Retief, leader of the Voortrekkers, and the British missionary Owen and American missionary Champion.

On the south side, just behind the main complex, were three separate enclosed groups of huts. The centre group was used by the uBheje women of the black isigodlo. In this area, they initiated chosen young girls into the service of the king.

Execution hill

[edit]KwaMatiwane, or Execution hill, is the ridge northeast of uMgungundlovu. It is so named after chief Matiwane who, around 1829/30, was executed here with his followers after they had gone against Dingane's rule. Reverend Francis Owen resided a short distance from the hill during the 1830s and remarked that the vultures circling over the bodies of those newly slain were a regular sight.[1]

Dingane would pronounce a verdict in the company of his chiefs and principal men, while the executioners, armed with knobbed clubs, would await their orders. The condemned were made to walk to this hill, their executioners following. Upon arriving at the spot, the condemned were clubbed to death. Their bodies were left in the open to be devoured by the birds by day, and hyenas by night. When a chief (induna) was condemned, his people shared the same fate.[1] Witches, identified as such by a witch doctor (sangoma), were instantly condemned to die without a hearing. Dingane's subjects were often executed for supposed witchcraft, besides possessing prohibited beads, wearing clothes of a particular colour, or clothes that resembled those worn by the king. Casting a glance at any of the king's 500 concubines was also punishable by death.[1]

Retief massacre

[edit]

28°25′37″S 31°16′12″E / 28.42694°S 31.27000°E

On 6 February 1838, Execution hill became the place where Dingane directed the killing of the Voortrekker Piet Retief and his entourage. The British missionary and his staff had warned Retief that he was in danger from Dingane, but the chief had won the trekkers' trust and they did not listen. Dingane had them killed after agreeing to a large cession of land (which he may not have fully understood, as the document was in English).

Despite warnings, Retief left the Tugela region on 28 January 1838, in the belief that he could negotiate with Dingane for permanent boundaries for the Natal settlement. The deed of cession of the Tugela-Umzimvubu region, although dated 4 February 1838, was signed by Dingane on 6 February 1838, with the two sides recording three witnesses each. Dingane invited Retief's party to witness a special performance by his soldiers. Dingane ordered his soldiers to capture Retief's party of 70 and their coloured servants.

Retief, his son, men, and servants, about 100 people in total, were taken to kwaMatiwane hill, the site where Dingane had thousands of other enemies executed. The Zulus killed the entire party by clubbing them and killed Retief last, so as to witness the deaths of his comrades. Their bodies were left on the hillside to be eaten by wild animals, as was Dingane's custom with his enemies. Dingane immediately directed the attack on the Voortrekker laagers, which plunged the migrant movement into serious disarray.

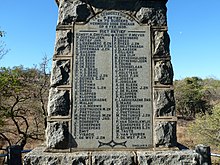

Following the decisive Voortrekker victory at Blood River, Andries Pretorius and his "victory commando" recovered the remains of the Retief party, and buried them in a mass grave on 21 December 1838. Also recovered was the undamaged deed of cession from Retief's leather purse, as later verified by a member of the "victory commando", E. F. Potgieter. An exact copy survives, though the original was presumably lost in transit to the Netherlands during the Anglo-Boer War.[4] The site of the Retief grave was more or less forgotten until pointed out in 1896 by J. H. Hattingh, a surviving member of Pretorius' commando. A monument recording the names of the members of Retief's delegation was erected near the grave in 1922.[5]

Dingane ruled until 1840. His forces were overwhelmingly defeated by the Boers at the Battle of Blood River. Leaders of his people assassinated him during a military expedition, and he was succeeded as king by his half-brother Mpande.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Bonar, Andrew Redman (1849). "1. Superstitions of the heathen: The Zulus". Incidents of Missionary Enterprise (3 ed.). Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson. pp. 15–21. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ a b Laband, John (1995). Rope of sand: the rise and fall of the Zulu Kingdom in the nineteenth century. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball. p. 66. ISBN 1-86842-023-X.

- ^ Mitchell, Peter (2002). The Archaeology of southern Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 373–375. ISBN 0-521-63389-3.

- ^ Wood, William (1840). "An Eyewitness Account of the Massacre of Retief". Statements Respecting Dingaan, King of the Zulus. Collard & Co. Archived from the original on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- ^ Stander, Eerw. P. P. Dingaanstat: die Graf van Piet Retief en Sy Sewentig Burgers.