Upper Mississippian culture

| |

| Geographical range | American Midwest |

|---|---|

| Period | Prehistoric, Protohistoric |

| Dates | c. 1000 — c. 1700 AD |

| Major sites | Oak Forest, Carcajou Point, Zimmerman, Anker, Fisher |

| Preceded by | Late Woodland |

| Followed by | New France |

The Upper Mississippian cultures were located in the Upper Mississippi basin and Great Lakes region of the American Midwest. They were in existence from approximately A.D. 1000 until the Protohistoric and early Historic periods (approximately A.D. 1700).[1][2]

Archaeologists generally consider "Upper Mississippian" to be an attenuated version of "Middle Mississippian" cultures represented at Cahokia and other sites exhibiting more complex social and political structures, perhaps at a chiefdom level of development. The Middle Mississippians were capable of forming large cities and were thus heavily dependent on agriculture to support large populations. This civilization had its origins about A.D. 1000 or slightly earlier, and was at its peak in the 12th and 13th centuries A.D. when the population at Cahokia was estimated to be 40,000 and the city itself covered an area of 3,480 acres (in contrast, Upper Mississippian sites are usually well under 10 acres). Although the Middle Mississippian declined after its peak, there were still advanced chiefdom-level societies present at the time of the DeSoto expedition in the 1530s and 1540s.[3][4]

The Upper Mississippians had their origins about the same time as the Middle Mississippians, around A.D. 1000. They attained larger populations and heavier emphasis on agriculture than the previous Late Woodland cultures but still relied to a large extent on hunting and gathering and lacked the chiefdom-level form of society and the large centralized cities. The Late Woodland peoples with their emphasis on small villages and hunting and gathering adaptation had previously occupied the Upper Mississippi Valley and Great Lakes Region prior to A.D. 1000. In some areas, the Late Woodland population persisted until European contact, and even occasionally coexisted in the same time and place with the Upper Mississippians.[5][3][1][2]

Most of the Upper Mississippian entities are grouped together under the Oneota aspect. The Grand River, Lake Winnebago, Koshkonong, Green Bay (aka Mero Complex), Orr and Utz are Foci grouped under Oneota. Fisher and Huber are placed by James A. Brown in an "unnamed tradition" (or focus) within the Oneota aspect. The Langford tradition is seen as contemporaneous with Fisher and Huber and is considered Upper Mississippian due to its similarity to Fisher material culture (especially pottery).[6][5][7] The Fort Ancient Aspect in the Ohio River Valley is sometimes considered an Upper Mississippian entity.[3]

Characteristics

[edit]The major diagnostic trait of the Upper Mississippian cultures is their use of shell to temper their pottery, a practice which they shared in common with the Middle Mississippians. In contrast, the Late Woodland pottery was grit-tempered up until European contact. The Langford Tradition pottery is actually grit-tempered, but is still designated as Upper Mississippian because of the stylistic similarities with Fisher Ware.[3]

Other than the pottery, the Upper Mississippian way of life was essentially similar to that of the Late Woodland cultures. They may have been slightly more dependent on maize agriculture, but hunting and gathering were still part of their subsistence base.[3][5]

The triangular projectile points called “Madison Points” are a trait the Upper Mississippians share with the Late Woodland. These artifacts were used for warfare, hunting and fishing, and are almost always present in large numbers at any site after A.D. 1000, usually dominating the stone tool assemblages. It may be that this reflects increased levels of conflict during this period.[2][8]

Other artifacts that are diagnostic of the Upper Mississippian cultures specifically are double-pointed biface knives, long thin ovate blades, uniface humpbacked end scrapers, expanding base drills, sandstone abraders (aka "arrow shaft straighteners"), elk or bison scapula hoes, deer metatarsal beamers, pot sherd discs that seem to have been used as spindle whorls, and antler or bone cylinders that appear to be game pieces.[9][10] In 1945 WC McKern provided a list of diagnostic traits he felt represented the Upper Mississippian cultures in Wisconsin.[11]

Origins

[edit]The origin of the Upper Mississippian cultures is a matter of debate among archaeologists. They may have been local Late Woodland populations who were influenced by the large-scale chiefdom entities; or they may have originated in one of these more advanced societies and set out to “colonize” the marginal areas to the north. Aztalan is a site that represents an incursion of Middle Mississippians into Wisconsin;[12] however, it is apparent that the Aztalan material culture is quite distinct from Upper Mississippian, so it does not necessarily follow that one evolved out of the other. There is evidence that from A.D. 1200-1500 there was a climatic cooling trend which appears to have made the growing system much less reliable in the Upper Mississippi area. This may have been why the culture “reverted” back to a smaller scale society with lesser dependence on agriculture for subsistence, and more emphasis on hunting and gathering.[3][10][7]

There is significant evidence that the Middle Mississippians and Upper Mississippians had frequent contact with each other. In particular, the Anker site near Chicago, Illinois, yielded grave goods with clear ties to the south including a mask gorget with a “weeping eye” motif which was also found on an artifact from the Nodena site in Arkansas, and is considered to be associated with the Southern Ceremonial Complex. It is unclear whether this represents trade or an actual movement of people from the Middle Mississippian heartland to the Great Lakes.[13]

Environment

[edit]The Upper Mississippian sites are mostly located on what is known as the Prairie Peninsula region of the American Midwest; including the states of Iowa, Missouri, Illinois, northern Indiana and southwestern Michigan. This was prime habitat for the bison, which comprised a major food source as well as raw material for bone tools. Archaeologists believe that the range of the bison did not extend across the Mississippi into Illinois until about A.D. 1600.[5]

Sites in the Prairie Peninsula are generally located in major river valleys like the Illinois or Mississippi. These areas were ideally suited for the inhabitants to access resources in several different ecosystems; the prairie (bison, elk); river bottoms (nuts, berries, wild turkey), oak savannas (deer, elk, bear, wild berries) and the river itself with associated marshes and wetlands (fish, water lily tubers, mussels, turtles, waterfowl).[5][14]

Other sites characterized as Upper Mississippian or Oneota are found farther north, in present day Minnesota and Wisconsin. These include the Tremaine Site Complex in Wisconsin and the Grand Meadow Chert Quarry and sites in the Blue Earth River Region in Minnesota. Settlement patterns and diets varied significantly across these sites. [15][16][17]

Architecture

[edit]

Several types of houses have been noted at Upper Mississippian sites. At the Huber sites of Oak Forest and Anker, large oval structures measuring from 25–55 feet long and 10–15 feet wide were excavated.[18][13][19] At the Fisher and Zimmerman sites, square to rectangular semi-subterranean wall-trench houses were found, similar to houses at the Middle Mississippian site of Aztalan.[20][21]

Forms of structures may have also changed over time. It was thought that the square houses found at the Zimmerman site may date to an earlier time period when growing seasons were more reliable and a settled agricultural life way led to construction of more substantial structures. Later structures at the site were much more ephemeral, and may represent temporary wigwams at a time period when growing seasons were less reliable and the hunting of bison contributed more to subsistence. The temporary structures facilitated movement as the bison herds were followed as part of a seasonal round.[21]

Pit features

[edit]

Most Upper Mississippian sites have large numbers of pit features which functioned as storage pits, refuse pits, roasting pits and hearths. The storage pits were thought to be constructed to help preserve food for extended periods of time; possibly through the winter, if the site is a permanent village. As the contents of these pits soured, they were converted to refuse pits. These pits often contain abundant information for archaeological analysis; pot sherds, lithic flakes and tools, animal bone, plant remains and occasionally even human remains.[7][15]

Mortuary customs

[edit]While the people associated with the Upper Mississippian sphere were not prolific mound builders (in contrast with Middle Mississippian cultures), they would often bury their dead under existing mounds built by other cultures or natural mound-like formations.[22] Examples include the Fisher Mound Group and Gentleman Farm site. Another notable exception was Aztalan which had three platform mounds.[23] However, a resurgence of mound building occurred towards the end of the 17th century, for example at the Oneota site of Blood Run. These mounds are linked to a cultural revitalization movement in response to European contact.[24]

Some Upper Mississippian sites consist of a village area in conjunction with a cemetery. Both extended burials and bundle burials are present. Other burials are found directly under houses.[22] Grave goods are present with some burials. It is common to see the deceased buried alongside material remains such as pottery, weapons, tools, or other utilitarian objects, as well as organic materials such as clams and mussels.[25] The most common artifacts included with burials are shell spoons and pottery vessels; at the Fisher Mound Group, the spoons and vessel interiors had a greasy feel, and small amounts of bone were present; implying that the pots contained food when they were buried.[26][20]

A large number of burials were excavated at the Anker Site which included exceptionally rich grave goods, implying they were wealthy or of higher status.[13]

Another site that has been well documented by archaeologists is the cemetery associated with Morton Village, called Norris Farms 36. A total of 264 people are buried there, and many of the bodies exhibit evidence of violent deaths. Injuries include decapitation, scalping, projectile wounds, and blunt force trauma. Indications of traumatic injuries are roughly distributed equally among men and women, suggesting that gender did not determine who would participate in warfare. Some children buried at Norris Farms 36 also suffered from violent injuries.[22] Many of the graves are associated with ceramic artifacts, most of which are Upper Mississippian in style. However, some ceramics, particularly those interred with children, are distinctly Middle Mississippian. One interpretation of this evidence is that children played an important role in bridging the gap between cultures at Morton Village.[27] Further evidence of this role include the fact that human hands were found interred with an infant. Additionally, many of the children buried at Norris Farms 36 were interred with carefully arranged avian remains. Both hands and birds are important symbols associated with Middle Mississippian culture.[27]

At the Aztalan and adjacent, Lake Koshkonong sites, there is also evidence of interpersonal violence.[23] In an excavation of human remains from both formal and informal burials at the site, 1402 disarticulated bones were uncovered, which would amount to anywhere from 84 and 92 people buried there. A significant number of the individuals buried at informal burials showed evidence of perimortem trauma such as cut marks, chop marks, fractures, and scalping.[23] Some scholars speculate that these injuries are due to internal conflict or mortuary practices.[23] Aztalan was also a heavily-fortified site, which is also considered evidence of violent conflict.[23]

At Lake Koshkonong, the settlements there exhibit no evidence of complex fortifications.[23] However, there is evidence of interpersonal violence from marks on the human remains at Lake Koshkonong. At the Crescent Bay Hunt Club site, a site in the Lake Koshkonong locality, 36% of the skeletons buried there show evidence of perimortem injuries.[23] Some of these injuries include cranial fractures and embedded projectiles.[23] While the inhabitants of Lake Koshkonong typically buried their dead in multigenerational graves, a large number of excavated skeletal remains were buried in random locations alongside general waste from the site, which could indicate high levels of interpersonal violence at Lake Koshkonong.[23]

In excavations of human remains done in the central Illinois River Valley, which was an area of cultural interaction between the Upper and Middle Mississippian, many skeletons were partially decomposed before burial.[28] While this physical evidence is typically interpreted as a sign of interpersonal violence, it is likely that this was a specific mortuary practice.[28] The recovery and interment of decomposing remains is believed to be rooted in Upper Mississippian mortuary ideology, which involved the movement of human remains over long distances long after they had died.[28] These practices likely played a role in preserving collective social memory and allowed for further engagement in surrounding landscape.[28]

Subsistence

[edit]The Upper Mississippian subsistence pattern had a primary emphasis on agriculture but hunting, gathering and fishing were also of importance. Compared to Late Woodland, the Upper Mississippian pattern tends to be more focused on efficient procurement of large-scale resources as opposed to utilizing every resource available. Therefore, efforts were focused on maize-beans-squash agriculture and hunting of large animals such as deer, elk and bison which provide significant amounts of meat to support larger populations.[5][10][9] Evidence from the Morton Village site in western Illinois demonstrates a combination of Upper Mississippian and Middle Mississippian agricultural and subsistence practices. [29]

At sites where flotation techniques were used to recover small-scale plant remanis, the Eastern Agricultural Complex (EAC) of cultivated seeds such as goosefoot (Chenopodium berlandieri), little barley (Hordeum pusillum), knotweed (Polygonum) and sumpweed (Iva annua) are often present. These seeds were first in use during Middle Woodland times and their use persisted until early Historic times.[30][31]

Gathering of wild plants was still an important economic activity and at Upper Mississippian sites sampled by flotation, the remains of plants such as nutshell (hickory nut, black walnut, hazelnut and acorn), wild rice, plum, wild grape, sumac, hawthorn and other wild seeds are commonly found.[2][1][30] Additionally, fish, freshwater mussels, and other aquatic resources were important in many Upper Mississippian sites. [15]

There are some sites showing evidence of focused seasonal resource exploitation of food sources such as sturgeon and water lily tubers. Sturgeon represented a potentially large supply of food at the time they made their annual spawning run. Specialized roasting pit features have been excavated at some sites which appear to be ethnographically documented by the early French explorers and described as “macopin roasting pits”. The tubers of American Lotus (Nelumbo lutea) and white water lily (Nymphaea tuberosa) have been recovered from roasting pits at some sites. At the Schwerdt and Elam sites on the Kalamazoo River in southwestern Michigan, sturgeon bone and American Lotus tubers were found together in the same roasting pits; indicating a specialized seasonal encampment.[21][10][32][33]

Daily life

[edit]The archaeological record often lacks evidence of daily activities because so much of the material culture is made of wood, fiber, plants and textiles that rarely survive for the archaeologist. However items made of bone, stone, shell, antler and copper usually survive and offer valuable glimpses into daily life.[citation needed]

At any given Upper Mississippian site, on a daily basis the Native American inhabitants undertook a variety of tasks and activities.[citation needed]

Evidence of hunting activities is found in the chipped stone projectile points. They were hafted to arrow shafts and used as bows-and-arrows.(Fenner 1963) They could also be used as spear points to harvest fish.[1] Arrow shafts were made of small branches that were straightened using a sandstone abrader. Bone and antler projectile points and harpoons are additional hunting and fishing implements commonly found at Upper Mississippian as well as Late Woodland sites.[10][9]

The Upper Mississippians occasionally went to war, and their main weapon was the bow-and-arrow tipped with a triangular projectile point. In the Protohistoric and early Historic periods additional artifacts such as gunflints and iron tomahawks provide evidence of conflict.[2][8][34]

A wide variety of stone knives was used in the butchering of meat; preparation of hides; cutting fibers or ropes; processing of plant foods; or any other domestic activity requiring a sharp cutting implement.[10][9] Sometimes knives made from scapula bone are also present in the archaeological record; which may be broken hoes that have been repurposed as knives.[10]

Hide-working required its own set of tools; knives to separate the skin from the body; beamers to de-hair the hide; scrapers to further process; drills and awls to punch holes if needed; and bone needles if sewing is required.[10][9][21]

Woodworking tools included adzes and axes to cut the large branches or the tree itself; scrapers and knives to shape the wood into the desired shape; and drills if holes or indentations are needed.[10][9]

Sewing activities utilizing bone needles took place in the manufacture of clothing and reed mats.[21][35]

The manufacture of stone tools was an essential activity in a Prehistoric society. In the archaeological record, it results in a number of waste flakes and unused “cores”.[2] Antler flakers and socketed antler “punches” which were used the knapping process are commonly recovered at Upper Mississippian sites.[10]

Hoes made out of elk or bison scapula were used during agricultural activities, or just for any digging function. They may have been used in the building of subterranean houses; in preparation for a burial; or to dig the pit features which are usually abundant at all Upper Mississippian sites: storage pits, refuse pits or roasting pits.[10][21]

Daily meal preparation and serving is one of the most basic of household functions and takes place multiple times a day. Usually this is well represented in the archaeological record in the form of cooking pots, serving instruments and animal bone. Where flotation techniques are used, additional information may be obtained in the form of small seeds and even wood charcoal from the hearths and roasting pits. Shell spoons used for serving implements have been found at several Upper Mississippian sites.[14] The cooking pots used for food cooking and storage often have encrusted food residue resulting from accidentally burning the contents. It's been noted that shell tempering adds some efficiency to the pottery vessel by allowing for thinner walls which result in lighter weights.[2] Most of the Upper Mississippian pottery wares feature handles which facilitate picking up and moving the vessels.[3]

The health of people living in Upper Mississippian sites varied significantly based on location and diet. Excavation and analysis of human remains from the Tremaine Site Complex in Wisconsin found that malnutrition was not a regular problem at the site. However, the same study found that the complex's inhabitants showed signs of childhood growth disruption and had deficiencies in fiber, calcium, folate, and Vitamin A, suggesting dietary issues. [15]

Human remains from the Tremaine Site Complex also demonstrated poor dental health, and 26% of the remains analyzed displayed signs of a bone condition called porotic hyperstosis. This condition is usually the result of anemia, which is often caused by deficiencies in iron. Archaeologists Ryan Tubbs and Jodie O'Gorman believe that the prevalence of porotic hyperstosis at the Tremaine Site Complex is likely the result of parasitic infections, as the human remains from that site all demonstrated very high levels of iron. [15]

In excavations of remains at the Aztalan and adjacent, Lake Koshkonong sites, there also is evidence of several health issues.[23] The inhabitants of Aztalan were likely overly dependent on maize, the staple food for Mississippian peoples.[23] This resulted in poor dental health as evidenced by the skeletal remains.[23] In addition, the inhabitants of Aztalan experienced a wide variety of health issues such as porotic hyperostosis, periosteal reaction, arthritis, as well as unspecified lesions.[23]

Like the inhabitants of Aztalan, inhabitants of Lake Koshkonong had a diet that was heavily dependent upon maize.[23] However, their diet appears to have been more diversified than Aztalan, as the Lake Koshkonong diet included higher proportions of foods like acorns and wild rice.[23] The inhabitants of Lake Koshkonong consumed low levels of meat and fish protein.[23] They experienced a wide array of dental issues like abscesses, caries, and linear enamel hypoplasia.[23] Linear enamel hypoplasia is when teeth fail to form correctly in children due to malnutrition and poor health, which also indicates that childhood malnutrition was present.[23]

Recreational/artistic/personal adornment/ceremonial life

[edit]These categories are combined because in Upper Mississippian culture (and Prehistoric Native American culture in general) the boundaries between them are blurred.

The bone and antler cylinders are thought to be game pieces. At the Fisher site, these game pieces are found in conjunction with a stone tablet which apparently taken together forms a “game set”.[26][10] It is possible that this was a gambling game, since early Native American tribes were observed to engage in gambling activities.[36][37]

Bone rasps (musical instrument) have been recovered and may have been used for making music for enjoyment or as part of a ceremony.[9][13]

Smoking pipes were also used for both recreational smoking and for use in a ceremony. Generally unstemmed pipes were for recreational use and stemmed pipes such as calumets were used for ceremonies.[9][14]

Many items of personal adornment have been recovered such as stone, bone and copper ornaments or pendants; bone plume holders and hair tubes made of bird bone. Some of these may have been worn on a daily basis but also may have been a part of a costume for a ceremony. In early Historic times, sometimes Jesuit rings have been found, indicating profession of Catholic faith as a result of French missionary activities.[21][35]

Works of art have been found at Upper Mississippian sites and it is probable that most of them were not looked upon simply for enjoyment or cultural appreciation, but for objects used by medicine men and/or to be used in ceremonies. These include mask gorgets with artistic motifs, engraved pebbles, and animal or bird figurines made of bone, shell or copper. A common artifact found in Late Prehistoric or Protohistoric components is a serpent figurine made of copper; in early Historic times these may be made from imported European copper.[10][13]

In general, the prehistoric Native American religious system was based on animism and polytheism. Objects were thought to have magical qualities; using them in ceremonies would help to appease or get the support of deities or totem animals; and putting them in graves may assist the deceased into the afterlife. Sometimes the bones of certain totem animals such as heron, bald eagle, crane, otter, or beaver were included in the grave, possibly as part of “medicine bundles”.[36][37][38]

Dogs were often sacrificed in order to entreat the gods prior to undertaking a difficult task or during an emergency. Dog meat was also eaten during ceremonies, so dog bone recovered from a site generally implies a spiritual or ceremonial context.[36][37]

It is also possible that certain entire sites were specialized for spiritual purposes, such as for conducting ceremonies or preparing burials for interment in a mound.[38]

Artifacts

[edit]Some representative artifacts of the Upper Mississippian cultures are displayed here:

| Material | Description | Image | Site | Function / Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chipped stone | Small triangular points (aka Madison points) |  | Moccasin Bluff site in Berrien County, Michigan[9] | Hunting/fishing/warfare |

| Chipped stone | Large leaf-shaped blade |  | Anker site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Domestic function / cutting applications |

| Chipped stone | Uniface humpback end scraper | Griesmer site in Lake County, Indiana[10] | Domestic function / processing wood or hides | |

| Chipped stone | Drills (expanding base) |  | Zimmerman site in LaSalle County, Illinois[21] | Domestic function / processing wood or hides |

| Stone | Sandstone abrader (aka arrow shaft straightener) |  | Anker Site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Domestic function / straightening arrow shafts for bows-and-arrows |

| Bone | Elk scapula hoes |  | Moccasin Bluff site in Berrien County, Michigan[9] | Domestic function / Agricultural-horticultural or general digging tool |

| Bone | Deer cannon bone beamer |  | Griesmer site in Lake County, Indiana[10] | Domestic function / hide-working tool |

| Antler | Antler harpoon | Fifield site in Porter County, Indiana[10] | Fishing function | |

| Antler | Antler projectile points; socketed and tanged |  | Griesmer site in Lake County, Indiana[10] | Hunting/fishing/warfare |

| Iron | Tomahawk |  | Zimmerman site in LaSalle County, Illinois[34] | Warfare function |

| Bone | Scapula knife or scraper |  | Griesmer site in Lake County, Indiana[10] | Domestic function / cutting applications |

| Bone | Matting needle |  | Hotel Plaza site in LaSalle County, Illinois[35] | Domestic function / sewing mats or clothing |

| Shell | Spoons |  | Zimmerman site in LaSalle County, Illinois[20] | Domestic function / Food preparation, serving |

| Bone | Bone cylinders or dice / game pieces |  | Anker site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Entertainment function |

| Bone | Styliform deer bone ornament (possibly a plume holder) |  | Zimmerman site in LaSalle County, Illinois[21] | Personal Adornment and/or Ceremonial function |

| Bone | Bone pendants (one in the shape of a bird and the other is fragmentary and in the shape of a wheel) |  | Zimmerman site in LaSalle County, Illinois[21] | Personal Adornment / Art Work |

| Bone | Bird bone tubes (may have been used for hair tubes; or possibly used by medicine men to "suck out" evil spirits) |  | Zimmerman site in LaSalle County, Illinois[21] | Personal Adornment and/or Ceremonial function |

| Brass | Jesuit finger rings | Hotel Plaza site in LaSalle County, Illinois[35] | Personal Adornment / Religious Function | |

| Stone | Elbow pipe fragment |  | Anker site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Ceremonial-Recreational function / pipe smoking |

| Stone | Disc pipe fragment |  | Anker site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Ceremonial-Recreational function / pipe smoking |

| Stone | Rectangular block-shaped pipe fragment |  | Anker site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Ceremonial-Recreational function / pipe smoking |

| Stone | Bear effigy pipe fragment (Whittlesey or Late Woodland style) |  | Anker site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Ceremonial-Recreational function / pipe smoking |

| Stone | Turtle-head effigy pipe fragment (Whittlesey or Late Woodland style) |  | Griesmer site in Lake County, Indiana[10] | Ceremonial-Recreational function / pipe smoking |

| Stone | Human head effigy pipe (Iroquoian style) |  | Anker site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Ceremonial-Recreational function / pipe smoking |

| Stone | Celt shaped pipe with incised decoration depicting bison and arrow |  | Anker site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Ceremonial-Recreational function / pipe smoking |

| Bone | Pipe stem made of human bone |  | Anker site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Ceremonial-Recreational function / pipe smoking |

| Bone | Rasp (musical instrument) made of human bone |  | Anker site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Ceremonial-Recreational function / entertainment or use at ceremony |

| Antler | Bird figurine with socketed pedestal |  | Anker site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Art work / Decorative and/or Ceremonial application |

| Bone | Wolf mandible pendant |  | Anker site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Personal Adornment and/or Ceremonial application |

| Bone | Snake vertebrae necklace |  | Anker site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Personal Adornment and/or Ceremonial application |

| Copper | Serpent effigy | Anker site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Personal Adornment and/or Ceremonial application | |

| Marine shell | Seashell duck effigy pendant |  | Oak Forest site in Cook County, Illinois[19] | Art work / Personal Adornment and/or Ceremonial application |

| Potsherd | Sherd pendant |  | Fifield site in Porter County, Indiana[10] | Art piece or Religious function |

| Shell | Mask gorget with "weeping eye" motif |  | Anker site in Cook County, Illinois[13] | Art Piece / Religious application |

Trade

[edit]There is ample evidence that the Upper Mississippian cultures traded amongst themselves as well as other cultures across a large area of the North American continent. The apparent connection with the Middle Mississippians has already been pointed out above; the shell gorget with “weeping-eye” motif and Middle Mississippian pottery vessels from the Anker site show a clear link to sites in Arkansas.[13][2][1]

Copper artifacts are often found at Upper Mississippian sites. These were apparently fashioned from the native copper located in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. It's unclear whether the copper was fashioned into artifacts in Michigan prior to trading to other areas, or if the Upper Mississippians traded for the raw copper and fashioned the artifacts themselves.[2][1]

Obsidian artifacts obtained at Upper Mississippian sites have been traced to volcanic sources in the Western Plains such as in modern day Wyoming and Idaho, and Southwest regions such as New Mexico. This suggests established trade relations with other cultures farther West.[39]

There are also signs of trade with the Iroquoian and Fort Ancient peoples to the east. Iroquoian pipes, Whittlesey-style pipes and Fort Ancient-like pottery have been found at Upper Mississippian sites.[13][10]

Trade between the individual Upper Mississippian tribes or populations can often be inferred through careful examination of the archaeological record. Minority pottery types are usually present in the form of a few vessels out of a complete assemblage that are of another ware group. Archaeologists often call these “trade vessels” but they could also result from intermarriage with neighboring tribes or other factors. In the early Historic Period it was often reported that two or more tribes shared a village and that would also result in multiple ware groups at the same site.[20][34][10]

Upper Mississippian traditions and pottery ware types

[edit]

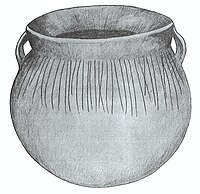

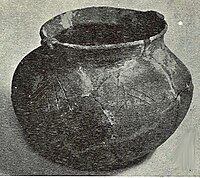

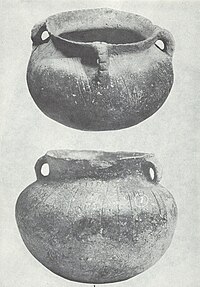

Upper Mississippian pottery usually comes in the form of globular, round-bottomed vessels commonly called “jars”, with restricted orifices and vertical to flared rim profiles. The different ware styles and types are based on differences in temper (shell or grit), surface finish (plain, smooth or cordmarked) and decorative techniques which usually occur on the section of the vessel between the rim and shoulder, and on the lip.[10][6][38][7][21] Occasionally other vessel forms are present, such as bowls with vertical sides, or shallow pans.[7]

Some representative complete and reconstructed Upper Mississippian vessels are illustrated below:

| Ware group | Type | Illustration | Site | Tempering material |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fisher Ware | Fifield Bold |  | Griesmer site in Lake County, Indiana[10] | Shell |

| Huber Ware | Huber Trailed |  | Griesmer site in Lake County, Indiana[10] | Shell |

| Langford Ware | Langford Trailed |  | Zimmerman site in LaSalle County, Illinois[21] | Grit |

| Langford Ware | Heally Trailed |  | Zimmerman site in LaSalle County, Illinois[34] | Grit |

| Orr focus | Allamakee Trailed |  | O'Regan site in Allamakee County, Iowa | Shell |

| Orr focus | Allamakee Trailed |  | Hogback site in Allamakee County, Iowa | Shell |

Some information on representative Upper Mississippian ware groups is presented in subsections below.

Huber phase (aka Blue Island)

[edit]- Representative sites: Griesmer, Huber, Palos, Hoxie Farm, Oak Forest, Anker, Knoll Spring (Au Sagaunashke Component), Zimmerman (minority type), Moccasin Bluff (Berrien Phase Groups 1, 2 and 3), Schwerdt (Berrien Phase)

- Pottery: Huber Ware, characterized by shell-tempering, predominantly plain surfaces and linear decorations[10][38]

- Radiocarbon Dates: A.D. 1520, 1530 (Griesmer),[10] A.D. 1425-1625 (Oak Forest),[18] A.D. 1590, 1640 (Moccasin Bluff),[9] A.D. 1445-1450 (Schwerdt)[32]

- Chronological trends: Early Huber is often cordmarked; has notched lips; and is decorated with medium- to wide-trailed lines. Late Huber is almost never cordmarked; notched lips decrease in frequency; and decorations are applied in fine-trailed lines. Huber is also thought to have derived from and/or replaced Fisher, since Fisher exhibits essentially the same traits as early Huber.[10][38]

- Sites with European trade goods: Palos, Oak Forest, Hoxie Farm

- Probable Ethnic Identification: Chiwere Sioux, Winnebago or Miami[41][10][9]

Fisher tradition

[edit]- Representative sites: Fisher Mound Group, Griesmer, Fifield, Moccasin Bluff (Berrien phase groups 4 and 5), Hoxie Farm (minority type)

- Pottery: Fisher Ware, characterized by shell-tempering, cordmarked surfaces and curvilinear decorations; lips are often notched[6][10]

- Radiocarbon Dates: A.D. 1520, 1530 (Griesmer)[10]

- Sites with European trade goods: Hoxie Farm

- Probable Ethnic Identification: Algonquian-speaking tribe[1]

Langford tradition

[edit]- Representative sites: Fisher Mound Group, Zimmerman (Heally Complex), Hotel Plaza (Upper Mississippian component), Gentleman Farm

- Pottery: Langford Ware, characterized by grit-tempering, cordmarked and smoothed surfaces, and curvilinear decorations[6][21][34]

- Radiocarbon Dates: A.D. 1630 (Zimmerman)[20]

- Sites with European trade goods: none

- Probable Ethnic Identification: Illinois or Kaskaskia[21][41][10]

Grand River focus

[edit]- Representative sites: Carcajou Point, Walker-Hooper

- Pottery: Grand River Ware, characterized by shell-tempered pottery with smooth surface and curvilinear decorations[7]

- Radiocarbon Dates: A.D. 998-1528[7]

- Sites with European trade goods: Carcajou Point

- Probable Ethnic Identification: Winnebago or Chiwere Sioux[7]

Koshkonong focus

[edit]- Representative sites: Carcajou Point, Summer Island (Upper Mississippian component)

- Pottery: Koshkonong Ware and Carcajou Ware, characterized by shell-tempered pottery with smooth surface and curvilinear decorations[7]

- Radiocarbon Dates: A.D. 998-1528[7]

- Sites with European trade goods: Carcajou Point

- Probable Ethnic Identification: Winnebago or Chiwere Sioux[7]

Orr focus

[edit]- Representative sites: Upper Iowa River Oneota site complex, Shrake-Gillies, Midway and Pammel Creek

- Pottery: Allamakee trailed[42]

- Radiocarbon dates: A.D. 1426-1660[5]

- Sites with European trade goods: Upper Iowa River Oneota site complex

- Probable ethnic identification: Ioway and Otoe

Green Bay focus (aka Mero complex)

[edit]- Representative sites: Mero

- Pottery: large proportion of grit-tempered pottery; handles and decoration are rare; related to Grand River focus

- Radiocarbon dates: none, but dated to A.D. 1200-1400 based on the artifacts present

- Sites with European trade goods: none

- Probable Ethnic Affiliation: unknown

See also

[edit]- Mississippi Valley: Culture, phase, and chronological periods table - List of archaeological periods

- List of Mississippian sites

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Quimby, George Irving (1960). Indian Life in the Upper Great Lakes: 11,000 B.C. to A.D. 1800. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mason, Ronald J. (1981). Great Lakes Archaeology. New York, New York: Academic Press, Inc.

- ^ a b c d e f g Griffin, James Bennett (1943). The Fort Ancient Aspect: Its Cultural and Chronological Position in Mississippi Valley Archaeology (1966 ed.). Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology.

- ^ Brose, David S. (1970). The Archaeology of Summer Island: Changing Settlement Systems in Northern Lake Michigan. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology, Anthropological Papers No. 41.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brown, James A.; Asch, David L. (1990). "Chapter 4: Cultural Setting: the Oneota Tradition". In Brown, James A.; O'Brien, Patricia J. (eds.). The Oak Forest Site: Investigations into Oneota Subsistence-Settlement in the Cal-Sag Area of Cook County, Illinois, IN At the Edge of Prehistory: Huber Phase Archaeology in the Chicago Area. Kampsville, Illinois: Center For American Archaeology.

- ^ a b c d Griffin, John W. (1948). "Upper Mississippi at the Fisher Site". American Antiquity. 14 (2): 124–126. doi:10.2307/275224. JSTOR 275224. S2CID 164036868.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hall, Robert L. (1962). The Archaeology of Carcajou Point. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.

- ^ a b Lepper, Bradley T. (2005). Ohio Archaeology (4th ed.). Wilmington, Ohio: Orange Frazer Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bettarel, Robert Louis; Smith, Hale G. (1973). The Moccasin Bluff Site and the Woodland Cultures of Southwestern Michigan. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology, Anthropological Papers No. 49.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Faulkner, Charles H. (1972). "The Late Prehistoric Occupation of Northwestern Indiana: A Study of the Upper Mississippi Cultures of the Kankakee Valley". Prehistory Research Series. V (1): 1–222.

- ^ McKern, Will C. (1945). "Preliminary Report on the Upper Mississippi Phase in Wisconsin". Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee. 16 (3): 109–285.

- ^ Barrett, S.A. (1933). "Ancient Aztalan". Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Bluhm, Elaine A.; Liss, Allen (1961). "The Anker Site". In Bluhm, Elaine A. (ed.). Chicago Area Archaeology. Urbana, Illinois: Illinois Archaeological Survey, Bulletin No. 3.

- ^ a b c Fenner, Gloria J. (1963). "The Plum Island Site, LaSalle County, Illinois". In Bluhm, Elaine A. (ed.). Reports on Illinois Prehistory: I. Urbana, Illinois: Illinois Archaeological Survey, Bulletin No. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Tubbs, Ryan M.; O'Gorman, Jodie A. (2005). "Assessing Oneota Diet And Health: A Community And Lifeway Perspective". Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology. 30 (1): 119–163. ISSN 0146-1109.

- ^ Trow, Tom; Wendt, Dan (2021). "The Grand Meadow Chert Quarry". The Minnesota Archaeologist. 77: 75–98 – via Research Gate.

- ^ Alex, Lynn Marie (2002). "Office of the State Archaeologist Educational series 7: Oneota". University of Iowa Digital Library. Iowa. Office of the State Archaeologist.

- ^ a b Brown, James A. (1990). Brown, James A.; O'Brien, Patricia J. (eds.). The Oak Forest Site: Investigations into Oneota Subsistence-Settlement in the Cal-Sag Area of Cook County, Illinois, IN At the Edge of Prehistory: Huber Phase Archaeology in the Chicago Area. Kampsville, Illinois: Center For American Archaeology.

- ^ a b Bluhm, Elaine A.; Fenner, Gloria J. (1961). "The Oak Forest Site". In Bluhm, Elaine A. (ed.). Chicago Area Archaeology. Urbana, Illinois: Illinois Archaeological Survey, Bulletin No. 3.

- ^ a b c d e Brown, James A. (1967). The Gentleman Farm Site. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Museum , Report of Investigations No. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Brown, James A. (1961). The Zimmerman Site: A Report on Excavations at the Grand Village of Kaskaskia, LaSalle County, Illinois. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Museum, Report of Investigations No. 9.

- ^ a b c A. O’Gorman, Jodie; Bengtson, Jennifer D.; Michael, Amy R. (2020-01-01). "Ancient history and new beginnings: necrogeography and migration in the North American midcontinent". World Archaeology. 52 (1): 16–34. doi:10.1080/00438243.2019.1736138. ISSN 0043-8243.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Krus, Anthony M; Richards, John D; Jeske, Robert J (2022). "Chronology for Mississippian and Oneota Occupations at Aztalan and the Lake Koshkonong Locality". American Antiquity. 87 (1): 124–41.

- ^ Betts, Colin M. (2010). "Oneota Mound Construction: An Early Revitalization Movement". Plains Anthropologist. 55 (214): 97–110. ISSN 0032-0447.

- ^ Rich, Jennifer. "Comparative study of human mortuary practices and cultural change in the upper Midwest." PhD diss., 2009.

- ^ a b Langford, George (1927). "The Fisher Mound Group: Successive Aboriginal Occupations near the Mouth of the Illinois River". American Anthropologist. 29 (3): 152–206. doi:10.1525/aa.1927.29.3.02a00260.

- ^ a b Bengtson, Jennifer D.; O'Gorman, Jodie A. (2016-01-02). "Children, Migration and Mortuary Representation in the Late Prehistoric Central Illinois River Valley". Childhood in the Past. 9 (1): 19–43. doi:10.1080/17585716.2016.1161910. ISSN 1758-5716.

- ^ a b c d Bengtson, Jennifer D (2022). "Death at Distance: Mobility, Memory, and Place among the Late Precontact Oneota in the Central Illinois River Valley". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 32 (3): 607–18.

- ^ Painter, Jeffrey M.; O’Gorman, Jodie A. (2019-06-26). "Cooking and Community: An Exploration of Oneota Group Variability through Foodways". Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology. 44 (3): 231–258. doi:10.1080/01461109.2019.1634327. ISSN 0146-1109.

- ^ a b Asch, David L.; Sidell, Nancy Asch (1990). "Chapter 13: Archaeobotany". In Brown, James A.; O'Brien, Patricia J. (eds.). The Oak Forest Site: Investigations into Oneota Subsistence-Settlement in the Cal-Sag Area of Cook County, Illinois, IN At the Edge of Prehistory: Huber Phase Archaeology in the Chicago Area. Kampsville, Illinois: Center For American Archaeology.

- ^ O'Gorman, Jodie (2003). "Revisiting the Moccasin Bluff Site". Michigan Archaeologist. 49 (1–2): 7–38.

- ^ a b Cremin, William M. (1980). "The Schwerdt site: A Fifteenth Century Fishing Station on the Lower Kalamazoo River, Southwest Michigan". Wisconsin Archaeologist. 61: 280–292.

- ^ DeRoo, Brian David (1991). Flotation Data Sampling Strategies in Archaeobotanical Research: An Experiment at the Elam Site (20AE195), Allegan County, Michigan (MA thesis). Kalamazoo, Michigan: Western Michigan University. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Brown, Margaret Kimball (1975). The Zimmerman Site: Further Excavations at the Grand Village of the Kaskaskia. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Museum, Report of Investigations No. 32.

- ^ a b c d Schnell, Gail Schroeder (1974). Hotel Plaza. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Museum, Report of Investigations No. 29.

- ^ a b c Kinietz, W. Vernon (1940). The Indians of the Western Great Lakes 1615-1760 (1991 ed.). Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- ^ a b c Blair, Emma Helen (1911). The Indian Tribes of the Upper Mississippi Valley and Region of the Great Lakes (1996 ed.). Omaha, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

- ^ a b c d e Herold, Elaine Bluhm; O'Brien, Patricia J.; Wenner, David J. Jr. (1990). Brown, James A.; O'Brien, Patricia J. (eds.). Hoxie Farm and Huber: Two Upper Mississippian Archaeological Sites in Cook County, Illinois, IN At the Edge of Prehistory: Huber Phase Archaeology in the Chicago Area. Kampsville, Illinois: Center for American Archaeology.

- ^ Logan, Brad; Hughes, Richard E.; Henning, Dale R. (2001). "Western Oneota Obsidian: Sources and Implications". Plains Anthropologist. 46 (175): 55–64. doi:10.1080/2052546.2001.11932057. ISSN 0032-0447.

- ^ Feathers, James K. (2006-06-01). "Explaining Shell-Tempered Pottery in Prehistoric Eastern North America". Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 13 (2): 89–133. doi:10.1007/s10816-006-9003-3. ISSN 1573-7764.

- ^ a b Brown, James A. (1990). "Chapter 5: Ethnohistoric Connections". In Brown, James A.; O'Brien, Patricia J. (eds.). The Oak Forest Site: Investigations into Oneota Subsistence-Settlement in the Cal-Sag Area of Cook County, Illinois, IN At the Edge of Prehistory: Huber Phase Archaeology in the Chicago Area. Kampsville, Illinois: Center For American Archaeology.

- ^ Wedel, Mildred Mott (1959). "Oneota Sites on the Upper Iowa River". The Missouri Archaeologist. 21 (2–4): 1–181.

Further reading

[edit]- Charles H. Faulkner (1972), "The Late Prehistoric Occupation of Northwestern Indiana: A Study of the Upper Mississippi Cultures of the Kankakee Valley", Prehistory Research Series, Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, Indiana, V (1): 1–222

- Robert Louis Bettarel; Hale Gilliam Smith (1973), The Moccasin Bluff Site and the Woodland cultures of southwestern Michigan

- Robert L. Hall (1962), The Archaeology of Carcajou Point, University of Wisconsin Press

- James A. Brown; Patricia J. O'Brien, eds. (1990), At The Edge of Prehistory: Huber Phase Archaeology in the Chicago Area, Center for American Archaeology

- James A. Brown, ed. (1961), The Zimmerman Site: A Report on Excavations at the Grand Village of Kaskaskia, LaSalle County, Illinois

- Margaret Kimball Brown (1975), The Zimmerman Site: Further Excavations at the Grand Village of Kaskaskia

- James Bennett Griffin (1943), The Fort Ancient Aspect: Its Cultural and Chronological Position in Mississippi valley Archaeology, University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology