Villard de Honnecourt

Villard de Honnecourt (Wilars dehonecort, Vilars de Honecourt) was a 13th-century artist from Picardy in northern France. He is known to history only through a surviving portfolio or "sketchbook" containing about 250 drawings and designs of a wide variety of subjects.

Life

[edit]Nothing is known of Villard apart from what can be gleaned from his surviving "sketchbook."[1] Based on the large number of architectural designs in the portfolio, it was traditionally thought that Villard was a successful, professional, itinerant architect and engineer.[2] This view is sometimes contested today, as there is no evidence of him ever working as an architect and the drawings contain some inaccuracies. However, Honnecourt compiled a manual that gave precise instructions for executing specific objects with explanatory drawings. In his writings he fused principles passed on from ancient geometry, medieval studio techniques, and contemporary practices. The author includes sections on technical procedures, mechanical devices, suggestions for making human and animal figures, and notes on the buildings and monuments he had seen. And his writings offer insights into the variety of interests and work of the 13th-century master mason in addition to providing an explanation for the spread of Gothic architecture in Europe.[3] He traveled to some of the major ecclesiastical building sites of his day to record details of these buildings. His drawing of one of the west facade towers of Laon Cathedral and those of radiating chapels and a main vessel bay, interior and exterior, of Rheims Cathedral are of particular interest.

Villard tells us, with pride, that he had been in many lands (Jai este en m[u]lt de tieres) and that he made a trip to Hungary where he remained many days (maint ior), but he does not say why he went there or who sent him. It has recently been proposed that he may have been a lay agent or representative of the cathedral chapter of Cambrai Cathedral to obtain a relic of St. Elizabeth of Hungary who had made a donation to the cathedral chapter and to whom the chapter dedicated one of the radiating chapels in their new chevet.[4] He also claimed to have made many of his drawings "from life" (al vif), an activity more usually associated with much later artists of the Renaissance.

Sketchbook

[edit]The "sketchbook" or "manual" of Villard de Honnecourt (more correctly, an album or portfolio) dates to about c.1225-1235. It was discovered in the mid-19th century and is presently housed in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), Paris, under the shelfmark MS Fr 19093. It consists of 33 parchment sheets measuring on average 235x155 mm, or 9.25 x 6.1 inches.[5] The manuscript is not complete and its original extent cannot be determined. Because the drawings and captions are oriented in many different directions, the album appears to have been assembled in an ad hoc fashion, as if the individual sheets were not originally intended to be bound together into book form. It is unclear whether it was Villard himself or a later party who assembled and bound the leaves into a book.[6]

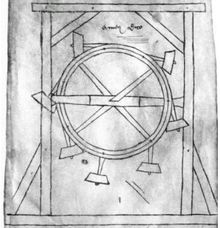

The album contains about 250 drawings. These include architectural designs (plans, elevations, and details, often of identifiable buildings), a great variety of human and animal subjects, ensembles of religious and secular figures perhaps derived from or intended as sculptural groups, ecclesiastical objects, mechanical devices (including a perpetual-motion machine), engineering constructions such as lifting devices and a water-driven saw, a number of automata, designs for war engines such as a trebuchet, and many other subjects. Many drawings are accompanied by annotations and labels.

The original purpose of the album is debatable. Originally it was thought to have served as a kind of training manual for practicing architects. This is rejected by some current researchers who think Villard's drawings seem ill-suited to such a purpose, though it can also be argued that the drawings are deliberately simplistic and abstracted to serve as coded mnemonic devices for architects who were initiated into the relevant oral tradition.[7]

Facsimiles

[edit]Several printed facsimiles of the album have appeared.

- (1859) Parker, J.H. and J. Facsimile of the Sketch-book of Wilars de Honnecourt, an Architect of the Thirteenth Century. London, 1859. - See(Lassus, Quicherat & Willis 1859).

- (1959) Bowie, Theodore. The Sketchbook of Villard de Honnecourt. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1959.

- (1972) Hahnloser, Hans R. Villard de Honnecourt. Kritische Gesamtausgabe des Bauhüttenbuches ms. fr. 19093 der Pariser Nationalbibliothek (2nd rev. ed.). Graz, 1972.

- (1986). Erlande-Brandenburg, Alain, et al. Carnet de Villard de Honnecourt. Paris, 1986.

- (2006) The Medieval Sketchbook of Villard de Honnecourt. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2006. (This publication contains the plates from Parker's 1859 edition accompanied by the introduction and captions from Bowie's 1959 edition.)

- (2009) Barnes, Carl F., Jr. The portfolio of Villard de Honnecourt (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Fr 19093): a new critical edition and color facsimile. Farnham; Burlington: Ashgate, 2009.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Villard De Honnecourt | Gothic architecture, drawings, Paris | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-09-08.

- ^ Gimpel, Jean (1976). The Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages. NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. pp. 114–146. ISBN 0030146364.

- ^ Gimpel, Jean (1984). The Cathedral Builders. New York: HarperPerennial. pp. 93–94. ISBN 0-06-09-1158-1.

- ^ BARNES, CARL F. JR. “An Essay on Villard de Honnecourt, Cambrai Cathedral, and Saint Elizabeth of Hungary,” New Approaches to Medieval Architecture, Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2011, pp. 77-91.

- ^ Bugslag, James (Oct–Dec 2001). "contrefais al vif: nature, ideas and the lion drawings of Villard de Honnecourt". Word & Image. 17 (4): 360–378. doi:10.1080/02666286.2001.10435726. S2CID 170295576.

- ^ Schlink, Wilhelm (1999). Joubert, Fabienne (ed.). "War Villard de Honnecourt Analphabet?". Pierre, Lumière, Couleur: études d'Histoire de l'Art du Moyen Age en l'Honneur d'Anne Prache. Paris: 213–222.

- ^ Beffeyte, Renaud. (2004). "The Oral Tradition and Villard de Honnecourt". Villard's Legacy: Studies in Medieval Technology, Science, and Art in Memory of Jean Gimpel, ed. Marie-Thérèse Zenner. Aldershot: Ashgate: 93–117.

References and further reading

[edit]- Barnes, Carl F., Jr. Villard de Honnecourt--the artist and his drawings: a critical bibliography. Boston, MA: G.K. Hall, 1982.

- Barnes, Carl F., Jr. "Le 'probleme' Villard de Honnecourt." In Les batisseurs des cathedrales gothiques, ed. Roland Recht (Strasbourg, 1989), pp. 209–223.

- Barnes, Carl F. JRr “An Essay on Villard de Honnecourt, Cambrai Cathedral, and Saint Elizabeth of Hungary,” New Approaches to Medieval Architecture, Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2011, pp. 77–91.

- Bugslag, James. “contrefais al vif: nature, ideas and the lion drawings of Villard de Honnecourt.” Word & Image 17, no. 4 (2001): 360–378.

- Gimpel, Jean. "Villard de Honnecourt: Architect and Engineer." In The Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages (NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976), pp. 114–142.

- Perkinson, Stephen. “Portraits and counterfeits: Villard de Honnecourt and thirteenth-century theories of representation.” In Excavating the Medieval Image: Manuscripts, Artists, Audiences: Essays in Honor of Sandra Hindman, eds. David S. Areford and Nina A. Rowe, 13–35. Aldershot and Burlington, VA: Ashgate, 2004.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus. "Villard de Honnecourt." In Pevsner on Art and Architecture, ed. Stephen Games (London: Methuen, 2002/2003), pp. 61–69.

- Rose, Leslie. "The Medieval Architect?: Villard de Honnecourt." In Leslie Rose, Artists of the Middle Ages(Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003), 61–80.

- Schlink, Wilhelm. “War Villard de Honnecourt Analphabet?” In Pierre, lumière, couleur : études d'histoire de l'art du Moyen Age en l'honneur d'Anne Prache, eds. Fabienne Joubert and Dany Sandron, 213–222. Paris: Presses de l'Université de Paris-Sorbonne, 1999.

- Key Figures in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia (Routledge Encyclopedias of the Middle Ages, Book 12), p. 651, ed. Richard K. Emmerson (London: Routledge, 2005).

- Wirth, Jean, Villard de Honnecourt. Architecte du XIIIe siècle, Genève, Droz, 2015.

- Zenner, Marie-Thérèse, ed. Villard’s Legacy: Studies in Medieval Technology, Science, and Art in Memory of Jean Gimpel. Aldershot, Hants., and Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate, 2004.

- Lassus, Jean Baptiste Antoine; Quicherat, Jules Etienne Joseph; Willis, Robert (1859), Facsimile of the sketch-book of Wilars de Honecort, an architect of the thirteenth century, London : John Henry and James Parker

External links

[edit] Media related to Villard de Honnecourt at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Villard de Honnecourt at Wikimedia Commons- AVISTA is a scholarly Villard de Honnecourt society for interdisciplinary study of medieval technology, science and art.

- La Cathedrale et Villard de Honnecourt at the French National Library has a sizeable number of sheets from Villard's portfolio.

- Association Villard de Honnecourt à Honnecourt"

- A full digital facsimile is available online via the BNF's online library, Gallica: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10509412z.r=villard%20de%20honnecourt