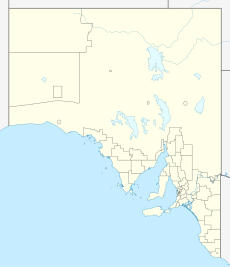

Wallaroo Mines, South Australia

| Wallaroo Mines Kadina, South Australia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Harvey's Pumping Station | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 33°57′58″S 137°41′53″E / 33.966202°S 137.698080°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 408 (SAL 2021)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 1860[2] | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 5554[3] | ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | Copper Coast Council | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Narungga[4] | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Grey[3] | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Footnotes | Coordinates[5] | ||||||||||||||

Wallaroo Mines is a suburb of the inland town of Kadina on the Yorke Peninsula in the Copper Coast Council area.[3] It was named for the land division in which it was established in 1860, the Hundred of Wallaroo, as was the nearby coastal town of Wallaroo. The boundaries were formally gazetted in January 1999 for "the long established name".[5]

History

[edit]With the arrival of British pioneers in the late 1830s and 1840s, pastoralists began grazing livestock in the vicinity but no permanent settlements were formed.

Development

[edit]On 17 December 1859, James Boor, a shepherd on the Wallaroo sheep run, owned by Walter Watson Hughes, discovered copper at what was to become Wallaroo Mines. Thirty or forty men were reportedly working at the site by the end of the year. By August 1860, the new copper mines employed 150 men and were "turning out ores of a rich quality", and by the end of 1860 there was a total population of 500. The mines had an enginehouse, office, a residence for the captain and secretary, and an assay office by this point, along with its own store for the miners. The growth of the mines saw the town of Kadina surveyed in 1860, with the first blocks being put up for sale in March 1861.[6] The proprietors formed the business into a private company, the Wallaroo Mining Company, with the first board meeting in August 1860 and Edward Stirling the first chairman.[7]

A settlement developed around the mine in 1860, described as "a collection of miners' cottages, sheds, mine shafts, enginehouses and other mine buildings".[2] A Primitive Methodist chapel was built in 1861.[8] A canvas structure that had served as a courthouse was moved from the mines to the present courthouse site in Kadina on 2 April 1861, with the "gipsy tent" police station following in January 1862. Lay Methodist services began at the mines in 1861, before a church was opened in Kadina in November 1862. In June 1862, the Kadina and Wallaroo Railway and Pier Company opened a horse-driven railway connecting the mines to the port at Wallaroo, with a branch into Kadina. It was subsequently bought out by the South Australian government on 1 March 1878, with the steam railway from Adelaide arriving in the same year; the old horse-driven line was later pulled up.[9] A Bible Christian church was built in 1866, and the Wallaroo Mines Wesleyan Methodist Church was built in 1867.[10]

Peak

[edit]The mine reached its peak between 1870 and 1875, when it had up to 1000 employees.[7] Wallaroo Mines Primary School opened on 31 January 1878 as the first public school in the Kadina area.[11][12] The mine temporarily closed from August 1878 until 1880 due to low copper prices, resulting in a large exodus from the district. It remained in restricted operations through much of the 1880s.[13][14] Wallaroo Mines Post Office opened on 1 July 1890.[15]

In 1889–90, the Wallaroo and Moonta Mines merged to form the Wallaroo and Moonta Mining and Smelting Company, becoming the largest industrial operation in South Australia.[7] Prior to their amalgamation, the Wallaroo Mine had produced 491,934 tonnes of copper, valued at £2,229,096, with dividends of £430,254. The production of the Wallaroo Mine outpaced that of the Moonta Mines in 1899.[16] 1n 1900, there was an outbreak of typhoid at Wallaroo Mines, and after a new doctor described the town's sanitary conditions as "disgusting and barbarous", the mining company undertook several improvements and mains water was introduced.[17] The Wallaroo Mines Institute was built by the mining company in 1902.[8] In 1904, a fire in Taylor's Shaft, then the main point of operations, lasted for over a month and cost £50,000, resulting in a "modernisation program" for the mine. The employment of the mine peaked in 1906 at a total of 2700 employees.[7]

Closure

[edit]The mines struggled in the years after World War I due to a downturn in the price of copper, closing for long periods and losing large amounts of money between 1919 and 1922. In November 1923, the mining company went into voluntary liquidation and the mine shut down.[18] The total production throughout its lifetime was about 165,000 tonnes with a value of £9.7 million.[19] The closure had a flow-on effect to the broader Kadina area, with an exodus from the region large enough to result in the closure of several churches and other facilities there.[20]

The Elders Engine House was demolished, with its stone being used several years later, in 1936, to build the new Kadina Catholic Church. The Primitive Methodist church was demolished in 1927.[21] The former Bible Christian church was demolished in the late 1930s; while it had closed as a church some decades before, it had later been used as a community hall and cinema.[10] Wallaroo Mines had a football club in the Yorke Peninsula Football Association as the "Federal Rovers"; however, the league went into recess in 1936.[22] A small store existed on Lipson Road for many years, run by Will Harwood from 1920. The original school building closed around 1967 and was demolished in 1977. Wallaroo Mines Post Office closed on 30 April 1976.[15] The Wallaroo Mines Methodist Church building was demolished in 1980, and the church subsequently moved into the Wallaroo Mines Institute.[8] An ore-processing plant was built on the former site of the school in 1988 by Moonta Mining NL, treating ore from their Poona mine 5 km north of Moonta; however, the Poona mine had closed by 1992.[23][24]

Wallaroo Mines today

[edit]

There is a self-guided walking trail around the former Wallaroo Mines site.[8] The former Harvey's Pumping Station (also known as Harvey's Enginehouse), dating from 1874, is the last of the former mine pumping stations to survive, and is listed on the South Australian Heritage Register.[25] The Kadina Heritage Trail also notes the site of an 1860 pioneer cemetery, the site of the former Methodist Church, the former police residence, the former post office, the mine explosives magazine, captains' residences, mine manager's residence ruins, the site of the Devon mine, and a number of old residences associated with the Wallaroo Mines settlement.[7] The Wallaroo Mines Primary School remains in operation on a new site to the north of the original location, and had 102 enrolled students in 2015.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Wallaroo Mines (suburb and locality)". Australian Census 2021 QuickStats. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ a b Drew, Greg (1990). Discovering Historic Kadina, South Australia. Department of Mines and Energy and the District Council of Northern Yorke Peninsula. p. 15.

- ^ a b c "Search result(s) for Wallaroo Mines, 5554". Location SA Map Viewer. Government of South Australia. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ Narungga (Map). Electoral District Boundaries Commission. 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Search result(s) for Wallaroo Mines, 5554". Property Location Browser. Government of South Australia. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ^ Bailey, Keith (1990). Copper City Chronicle: A History of Kadina. pp. 7–9.

- ^ a b c d e Drew, Greg (1990). Discovering Historic Kadina, South Australia. Department of Mines and Energy and the District Council of Northern Yorke Peninsula. p. 4.

- ^ a b c d Drew, Greg (1990). Discovering Historic Kadina, South Australia. Department of Mines and Energy and the District Council of Northern Yorke Peninsula. pp. 21–22.

- ^ Bailey, Keith (1990). Copper City Chronicle: A History of Kadina. pp. 16–18, 21, 49.

- ^ a b Bailey, Keith (1990). Copper City Chronicle: A History of Kadina. pp. 153–155.

- ^ "MEMORABILIA, 1878". Adelaide Observer. Vol. XXXVI, no. 1944. 4 January 1879. p. 22. Retrieved 28 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Bailey, Keith (1990). Copper City Chronicle: A History of Kadina. p. 31.

- ^ "Closing of the Wallaroo Mine". Evening Journal. Vol. X, no. 2935. Adelaide. 26 August 1878. p. 3 (Second Edition). Retrieved 28 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Bailey, Keith (1990). Copper City Chronicle: A History of Kadina. p. 45.

- ^ a b "Wallaroo Mines". Post Office Reference. Premier Postal. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ^ "IMPORTANCE OF THE WALLAROO MINES". Adelaide Observer. Vol. LXI, no. 3, 251. 23 January 1904. p. 34. Retrieved 28 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Bailey, Keith (1990). Copper City Chronicle: A History of Kadina. pp. 87–88.

- ^ Bailey, Keith (1990). Copper City Chronicle: A History of Kadina. p. 125.

- ^ Drew, Greg (1990). Discovering Historic Kadina, South Australia. Department of Mines and Energy and the District Council of Northern Yorke Peninsula. pp. 9–10.

- ^ Bailey, Keith (1990). Copper City Chronicle: A History of Kadina. pp. 21, 45.

- ^ Drew, Greg (1990). Discovering Historic Kadina, South Australia. Department of Mines and Energy and the District Council of Northern Yorke Peninsula. pp. 30, 152.

- ^ Bailey, Keith (1990). Copper City Chronicle: A History of Kadina. p. 163.

- ^ Drew, Greg (1990). Discovering Historic Kadina, South Australia. Department of Mines and Energy and the District Council of Northern Yorke Peninsula. p. 30.

- ^ "Poona and Wheal Hughes Cu Deposits, Moonta, South Australia" (PDF). Cooperative Research Centre for Landscape Environments and Mineral Exploitaiton. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ "Former Harvey's Pumping Station". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ^ "2015 Site Summary Statistics" (PDF). Department for Education and Child Development. Retrieved 28 January 2017.