Wood duck

| Wood duck Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Male (above) and female wood ducks, both at the Wissahickon Creek, Philadelphia. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | Aix |

| Species: | A. sponsa |

| Binomial name | |

| Aix sponsa | |

| |

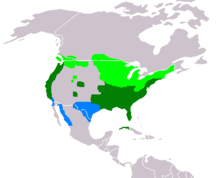

| Range of A. sponsa Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range | |

| Synonyms | |

| Anas sponsa (Linnaeus, 1758)Lampronessa sponsa | |

The wood duck or Carolina duck (Aix sponsa) is a partially migratory species of perching duck found in North America. The male is one of the most colorful North American waterfowls.[2][3]

Taxonomy

[edit]The wood duck was formally described in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Anas sponsa.[4] Linnaeus based his account on the "summer duck" from Carolina that had been described and illustrated by the English naturalist Mark Catesby in the first volume of his The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands that was published between 1729 and 1731.[5] Linnaeus specified the type locality as North America but this has been restricted to Carolina following Catesby.[6] The wood duck is now placed together with the mandarin duck in the genus Aix that was introduced in 1828 by the German naturalist Friedrich Boie. The species is monotypic: no subspecies are recognised.[7] The genus name is an Ancient Greek word for an unidentified diving bird mentioned by Aristotle. The specific epithet sponsa is Latin meaning "bride" (from spodere meaning "pledge").[8]

Description

[edit]The wood duck is a medium-sized perching duck. A typical adult is from 47 to 54 cm (19 to 21 in) in length with a wingspan of between 66 and 73 cm (26 and 29 in). The wood duck's weight ranges from 454–862 grams (16.0–30.4 oz).[9] This is about three-quarters the length of an adult mallard. It shares its genus with the Asian mandarin duck (Aix galericulata).[2]

The adult male has stunning multicolored iridescent plumage and red eyes, with a distinctive white flare down the neck. The female, less colorful, has a white eye-ring and a whitish throat. Both adults have crested heads. The speculum is iridescent blue-green with a white border on the trailing edge.[10]

The male's call is a rising whistle, jeeeeee; the females utter a drawn-out, rising squeal, do weep do weep, when flushed, and a sharp cr-r-ek, cr-e-ek for an alarm call.[11]

Distribution

[edit]The birds are year-round residents in parts of its southern range, but the northern populations migrate south for the winter.[12][13] They overwinter in the southern United States near the Atlantic Coast. 75% of the wood ducks in the Pacific Flyway are non-migratory.[13] Due to their attractive plumage, they are also popular in waterfowl collections and as such are frequently recorded in Great Britain as escapees—populations have become temporarily established in Surrey in the past, but are not considered to be self-sustaining in the fashion of the closely related mandarin duck.[citation needed] Along with the mandarin duck, the wood duck is considered an invasive species in England and Wales, and it is illegal to release them into the wild.[14] Given its native distribution, the species is also a potential natural vagrant to Western Europe and there have been records in areas such as Cornwall, Scotland and the Isles of Scilly, which some observers consider may relate to wild birds; however, given the wood duck's popularity in captivity, it would be extremely difficult to prove their provenance.[citation needed] There is a small feral population in Dublin.[citation needed]

Behavior

[edit]Breeding

[edit]Their breeding habitat is wooded swamps, shallow lakes, marshes, ponds and creeks in the eastern United States, the west coast of the United States, some adjacent parts of southern Canada, and the west coast of Mexico. They get their name from being one of the only species of ducks who perch and nest in trees. In recent decades, the breeding range has expanded towards the Great Plains. Currently most breeding occurs in the Mississippi alluvial valley.[15] They usually nest in cavities in trees close to water, although they will take advantage of nesting boxes in wetland locations. Other species may compete with them for nesting cavities, such as birds of prey, as well as mammals such as grey squirrels, and these animals may also occupy nest boxes meant for wood ducks. Wood ducks may end up nesting up to a mile away from their water source as a result.[16] Females line their nests with feathers and other soft materials, and the elevation provides some protection from predators such as raccoons, owls, and hawks.[17] Unlike most other ducks, the wood duck has sharp claws for perching in trees and can, in southern regions, produce two broods in a single season—the only North American duck that can do so.[11]

Wood ducks typically lay their first eggs from February to April.[18] Females typically lay seven to fifteen eggs which are incubated for an average of thirty days.[11] However, if nesting boxes are placed too close together, females may lay eggs in the nests of their neighbours, which may lead to nests with thirty eggs or more and unsuccessful incubation—a behaviour known as "nest dumping".[19][20]: 7

The day after they hatch, the precocial ducklings climb to the opening of the nest cavity and jump down from the nest tree to the ground. The morning after hatching the hen will leave the nest to feed and also make sure it is safe for her chicks. When she decides its safe she uses a maternal call to call the chicks out. Wood duck nests are over water to brace the fall when the chicks jump they can jump from as high as 50 feet.[18] The mother calls them to her and guides them to water.[17] The ducklings can swim and find their own food by this time. Wood ducks prefer nesting over water so the young have a soft landing.

Food and feeding

[edit]Wood ducks feed by dabbling (feeding from the surface rather than diving underwater) or grazing on land. They mainly eat berries, acorns, and seeds, but also insects, making them omnivores.[17] They are able to crush acorns after swallowing them within their gizzard.[21][22]

Conservation

[edit]The population of the wood duck was in serious decline in the late 19th century as a result of severe habitat loss and market hunting for both meat and plumage for the ladies' hat market in Europe. By the beginning of the 20th century, wood ducks had become rare, almost disappearing in many areas. In response to the Migratory Bird Treaty, established in 1916, and enactment of the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, wood ducks finally began to repopulate. By enforcing existing hunting regulations and protecting woodland and marsh habitat, wood duck populations began to rebound starting in the 1920s. The erection of nesting boxes starting in the 1930s further assisted wood duck conservation.[20] A synopsis of evidence from multiple studies performed by Williams et al. (2020) concluded that providing artificial nesting sites for wildfowl, including wood ducks, is beneficial.[23] Wood duck boxes have been found to be less effective than natural, hollow, dead trees but remain overall beneficial for the population.[24]

Landowners as well as park and refuge managers can encourage wood ducks by building wood duck nest boxes near lakes, ponds, and streams. Fulda, Minnesota, has adopted the wood duck as an unofficial mascot, and a large number of nest boxes can be found in the area.[citation needed]

Expanding North American beaver (Castor canadensis) populations throughout the wood duck's range have also helped the population rebound as beavers create an ideal forested wetland habitat for wood ducks.[13]

The population of the wood duck has increased a great deal in the last several years. The increase has been due to the work of many people constructing wood duck boxes and conserving vital habitat for the wood ducks to breed. During the open waterfowl season, U.S. hunters have been allowed to take only two wood ducks per day in the Atlantic and Mississippi Flyways. However, for the 2008–2009 season, the limit was raised to three. The wood duck limit remains at two in the Central Flyway and at seven in the Pacific Flyway. It is the second most commonly hunted duck in North America, after the mallard.[citation needed]

In popular culture

[edit]In 2013, the Royal Canadian Mint created two coins to commemorate the wood duck. The two coins are each part of a three coin set to help promote Ducks Unlimited Canada as well as celebrate its 75th anniversary.[25]

Gallery

[edit]- A Frontal View of a Drake

- Duckling

- A breeding pair

- Hen with two of her young swimming behind.

- Close up of the drake's head

- Drake in profile

- Male in eclipse plumage

- A female at Yellow Lake in Washington state

- A female swimming

- Lifting off from the water surface

- Taking off from ice

- Male in flight profile

- A male bird walking

- Male grooming himself

- Wood duck drake in New York

- Wood duck in Toronto

- drake in profile, Chicago

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Aix sponsa". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22680104A92843477. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22680104A92843477.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Wood Duck". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Dawson, William (2007). Neher, Anna (ed.). Dawson's Avian Kingdom Selected Writings. California Legacy. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-1-59714-062-1.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 128.

- ^ Catesby, Mark (1729–1732). The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands (in English and French). Vol. 1. London: W. Innys and R. Manby. p. 97, Plate 97.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 457.

- ^ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (December 2023). "Screamers, ducks, geese & swans". IOC World Bird List Version 14.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 37, 363. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ "Wood Duck Identification". All About Birds, TheCornellLab of Ornithology. Cornell University. 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ Gough, G.A.; Sauer, J.R.; Iliff, M. (1998). "Wood duck Aix sponsa". Patuxent Bird Identification Infocenter. Version 97.1. Laurel, Maryland: Eastern Ecological Science Center. Retrieved 20 February 2023 – via U.S. Geological Survey.

- ^ a b c "Wood Duck". Ducks Unlimited Canada. Archived from the original on 11 March 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ "Wood Duck". Hinterland's Who's Who. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ a b c "Wood Duck". BirdWeb: The Birds of Washington State. Seattle Audubon Society. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ^ Schedule 9 to the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981

- ^ "Wood Duck". Ducks Unlimited. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ Hoch, Greg (2020). "Cavities and Boxes". With Wings Extended. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-60938-695-5.

- ^ a b c "Wood Duck Fact Sheet, Lincoln Park Zoo". lpzoo.org. Archived from the original on 20 December 2015.

- ^ a b "10 Fun Facts About the Wood Duck". Audubon. 15 January 2024 [13 December 2023]. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Wood Duck (Aix sponsa) Dump-Nests". USGS. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. 1 February 2013. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013.

- ^ a b Wood Duck (Aix sponsa) Fish and Wildlife Habitat Management Leaflet (PDF) (Report). USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ Robbins, Chandler S.; Bruun, Bertel; Zim, Herbert S. (1983). Birds of North America: A Guide to Field Identification. Illustrated by Arthur Singer (Revised ed.). New York: Golden Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-307-37002-X.

- ^ Morris, Ron (16 April 2021) [15 February 2013]. "Birds use different methods to eat". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ Williams, D.R.; Child, M.F.; Dicks, L.V.; Ockendon, N.; Pople, R.G.; Showler, D.A.; Walsh, J.C.; zu Ermgassen, E.K.H.J.; Sutherland, W.J. (2020). "Bird Conservation". In Sutherland, W.J.; Dicks, L.V.; Petrovan, S.O.; Smith, R.K. (eds.). What Works in Conservation 2020. Cambridge, U.K.: Open Book Publishers. pp. 137–281. ISBN 978-1-78374-833-4. Retrieved 20 March 2023 – via Conservation Evidence.

- ^ Semel, Brad; Sherman, Paul W. (Autumn 1995). "Alternative Placement Strategies for Wood Duck Nest Boxes". Wildlife Society Bulletin. 23 (3): 463–471. ISSN 0091-7648. JSTOR 3782956.

- ^ "Royal Canadian Mint Coins Celebrate the 75th Anniversary of Ducks Unlimited Canada While Honouring Other Icons of Canadian Nature, Culture And History". Royal Canadian Mint. 6 March 2013. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

External links

[edit]- Wood Duck Society

- BirdLife species factsheet for Aix sponsa

- "Wood Duck media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Wood duck photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)