2022 Winter Olympics

Emblem of the 2022 Winter Olympics | |

| Location | Beijing, China |

|---|---|

| Motto |

|

| Nations | 91 |

| Athletes | 2,871 |

| Events | 109 in 7 sports (15 disciplines) |

| Opening | 4 February 2022 |

| Closing | 20 February 2022 |

| Opened by | |

| Closed by | |

| Cauldron | |

| Stadium | Beijing National Stadium |

Winter Summer 2022 Winter Paralympics | |

The 2022 Winter Olympics, officially called the XXIV Olympic Winter Games (Chinese: 第二十四届冬季奥林匹克运动会; pinyin: Dì Èrshísì Jiè Dōngjì Àolínpǐkè Yùndònghuì) and commonly known as Beijing 2022 (北京2022), were an international winter multi-sport event held from 4 to 20 February 2022 in Beijing, China, and surrounding areas with competition in selected events beginning 2 February 2022.[1] It was the 24th edition of the Winter Olympic Games.

Beijing was selected as host city on 31 July 2015 at the 128th IOC Session in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, marking its second time hosting the Olympics, and the last of three consecutive Olympics hosted in East Asia following the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang County, South Korea, and the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, Japan. Having previously hosted the 2008 Summer Olympics, Beijing became the first city to have hosted both the Summer and Winter Olympics. The venues for the Games were concentrated around Beijing, its suburb Yanqing District, and Zhangjiakou, with some events (including the ceremonies and curling) repurposing venues originally built for Beijing 2008 (such as Beijing National Stadium and the Beijing National Aquatics Centre).

The Games featured a record 109 events across 15 disciplines, with big air freestyle skiing and women's monobob making their Olympic debuts as medal events, as well as several new mixed competitions. A total of 2,871 athletes representing 91 teams competed in the Games, with Haiti and Saudi Arabia making their Winter Olympic debut.

Beijing's hosting of the Games was subject to various concerns and controversies including those related to human rights violations in China, such as the persecution of Uyghurs in China, which led to calls for a boycott of the games.[2][3] Like the Summer Olympics held six months earlier in Tokyo, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the implementation of health and safety protocols, and, for the second Games in a row, the Games being closed to the public (with selected events open to invited guests at a reduced capacity).

Norway finished at the top of the medal table for the second successive Winter Olympics, winning a total of 37 medals, of which 16 were gold, setting a new record for the largest number of gold medals won at a single Winter Olympics. The host nation China finished fourth with nine gold medals and also eleventh place by total medals won, marking its most successful performance in Winter Olympics history.[4][5][6]

Bidding process

[edit]The bidding calendar was announced by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in October 2012, with the application deadline set for 14 November 2013.[7] The IOC Executive Board reviewed the bids from all applicant cities on 7 July 2014 and selected three cities, Oslo (Norway), Almaty (Kazakhstan), and Beijing (China), as the final candidates.[8]

Several bid cities withdrew their bids during the process, citing the high costs or the lack of local support and funding for hosting the Games.[9] The Oslo bid, considered the clear frontrunner, was canceled in the wake of a series of revelations about the IOC's demands for luxury treatment of IOC members that strongly turned public opinion and the parliamentary majority against the bid. The city withdrew its application for government funding after a majority of the Norwegian parliament had stated their intention to decline the application. In the days before the decision, Norwegian media had revealed the IOC's "diva-like demands for luxury treatment" for the IOC members themselves, such as special lanes on all roads only to be used by IOC members and cocktail reception at the Royal Palace with drinks paid for by the royal family. The IOC also "demanded control over all advertising space throughout Oslo" to be used exclusively by IOC's sponsors, something that is not possible in Norway because the government doesn't own or control "all advertising space throughout Oslo" and has no authority to give a foreign private organization exclusive use of a city and the private property within it.[10] Several commentators pointed out that such demands were unheard of in a western democracy; Slate described the IOC as a "notoriously ridiculous organization run by grifters and hereditary aristocrats."[11][12][13][14] Ole Berget, deputy minister in the Finance Ministry, said "the IOC's arrogance was an argument held high by a lot of people."[15] The country's largest newspaper commented that "Norway is a rich country, but we don't want to spend money on wrong things, like satisfying the crazy demands from IOC apparatchiks. These insane demands that they should be treated like the king of Saudi Arabia just won't fly with the Norwegian public."[15]

Beijing was selected as the host city of the 2022 Winter Olympics after beating Almaty by four votes on 31 July 2015 at the 128th IOC Session in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

| City | Nation | Votes |

|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 44 | |

| Almaty | 40 |

Development and preparations

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2022) |

Venues

[edit]

In February 2021, Beijing announced that the 26 venues (including training venues) for these sports would be running on entirely renewable energy.[16][17]

There were three different clusters of venues designed and constructed for the 2022 Winter Olympics, each respectively known as the Beijing Zone, the Zhangjiakou Zone, and the Yanging Zone.[18]

Beijing Zone

[edit]Venues in the Beijing Zone exist in different conditions; some were recently constructed exclusively for the 2022 games, while the rest were renovated from the 2008 Summer Olympics or other existing sites.[19] The Beijing Zone of the 2022 Winter Olympics consisted of six competition venues and was where the Opening and Closing Ceremonies, for both the 2022 Winter Olympics and 2008 Summer Olympics, would take place.[19]

Five ice events were held at the Olympic Green, the Capital Indoor Stadium and the Beijing Wukesong Sports Center, which had been some of the main venues of the 2008 Summer Olympics. The Big Air snowboarding and freestyle skiing events were held in a former industrial area in Shijingshan District, at Western Hills area.[20] Since the end of 2009, the Beijing Olympic Village apartments on the Olympic Green had been transformed into a residential area. There was therefore a need to build another Olympic Village on a smaller scale for the Winter Olympics. These new buildings are located in the southern area of Olympic Green on the neighbourhood of the National Olympic Sports Center and will serves as Chinese Olympic Committee residential complex for those athletes who will undergo training sessions at the nearby venues.[21]

The Beijing National Stadium was an iconic venue in the Beijing Zone, and it is also known as the Bird's Nest (鸟巢; Niǎocháo). The Beijing National Stadium was the site that hosted the Opening and Closing Ceremonies for the 2022 Winter Olympics, but it was no longer a venue for any competition in 2022.[22]

The National Aquatics Center (国家游泳中心 Guójiā Yóuyǒng Zhōngxīn /gwor-jyaa yoh-yong jong-sshin/), also known as the Water Cube, was the venue for Curling competition.[23] In the 2022 Winter Olympics, the National Aquatics Center became the first Olympic venue to incorporate a curling track in the swimming pool.[24]

The Shougang Big Air (首钢滑雪大跳台中心 Shǒugāng Huáxuě Dàtiàotái Zhōngxīn /shoh-gung hwaa-sshwair daa-tyao-teye jong-sshin/) was a newly constructed site for the 2022 Winter Olympics.[25] The Shougang Big Air hosted the freestyle skiing and snowboarding events.

The Wukesong Sports Centre (五棵松体育馆 Wǔkēsōng Tǐyùguǎn /woo-ker-song tee-yoo-gwan/) was under an 8-month renovation for the 2022 Winter Olympics. In February 2022, the Wukesong Sports Centre hosted the 2022 Winter Olympics Men's and Women's ice hockey tournaments.[26]

The National Indoor Stadium (国家体育馆 Guójiā Tǐyùguǎn /gwor-jyaa tee-yoo-gwan/) was the second venue for the ice hockey tournament for the 2022 Winter Olympics, besides the Wukesong Sports Centre.[27]

The National Speed Skating Oval (国家速滑馆 Guójiā Sùhuáguǎn /gwor-jyaa soo-hwaa-gwan/) has the nickname "Ice Ribbon" due to its exterior design. The National Speed Skating Oval was the venue for speed skating in the 2022 Winter Olympics.

The Capital Indoor Stadium (首都体育馆 Shǒudū Tǐyùguǎn), also known as the Capital Gymnasium, was a venue adapted from the 2008 Summer Olympics and was reconstructed for short-track speed skating and figure skating competitions in the 2022 Winter Olympics.[28]

- Beijing National Stadium – opening, awarding and closing ceremonies / 80,000 existing

- Beijing National Aquatics Centre – curling / 3,795 renovated

- Beijing National Indoor Stadium – ice hockey / 19,418 existing

- Beijing National Speed Skating Oval – speed skating / 11,950 new

- Capital Indoor Stadium – figure skating, short track speed skating / 13,289 existing

- Wukesong Sports Centre – ice hockey / 15,384 existing

- Big Air Shougang – snowboarding (Big Air), freestyle skiing (Big Air) – 4,912 new

- Beijing 2022 Winter Olympic Village – new

Yanqing District is a suburban district localized at the Beijing's far north. Competitions for luge, skeleton, bobsleigh and alpine skiing were held in Xiaohaituo Mountain area in the West Dazhuangke village[29] of Zhangshanying in Yanqing District, northwest of the urban area of Beijing, 90 kilometres (56 miles) away from the city center of Beijing and 17.5 kilometres (10.9 miles) away from the town of Yanqing, using artificial snow because of the rarity of natural snow in this region.[30][31]

- National Alpine Ski Centre (Rock, Ice River) – alpine skiing 4,800 new

- National Sliding Centre – bobsleigh, luge, skeleton / 7,400 new

- Yanqing Olympic Village / new

Zhangjiakou Zone

[edit]All other skiing events were held in Taizicheng Area in Chongli District, Zhangjiakou city, Hebei province. It is 220 km (140 mi) from downtown Beijing and 130 km (81 mi) away from Xiaohaituo Mountain Area. The ski resort earned over ¥ 1.54 billion (US$237.77 million) in tourism during the 2015–16 winter season for a 31.6% growth over the previous season. In 2016, it was announced that Chongli received 2.185 million tourists, an increase of 30% from the previous season, during the first snow season after winning the Olympic bid. The snow season lasted for five months from November, during which Chongli has hosted thirty-six competitions and activities, such as Far East Cup and Children Skiing International Festival. A total of twenty-three skiing camps have also been set up, attracting the participation of 3,800 youths. All the venues construction started in November 2016 and was finished by the end of 2020 to enable the city to hold test events.[32][needs update]

- Snow Ruyi – ski jumping, Nordic combined (ski jumping) 6,000

- National Biathlon Centre – biathlon 6,024

- Genting Snow Park

- Park A – Ski and snowboard cross 1,774

- Park B – Halfpipe and Slopestyle (freestyle skiing and snowboard) 2,550

- Park C – Aerials and Moguls 1,597

- National Cross-Country Centre – Nordic combined (cross-country), cross-country 6,023

- Zhangjiakou Olympic Village

- Zhangjiakou Medals Plaza

Medals

[edit]The design for the Games' medals was unveiled on 26 October 2021. The concept is based on the 2008 Summer Olympics medals and Chinese astronomy and astrology as the games were held coinciding with the Chinese New Year festivities.[33]

The uniforms for medal presenters at medal ceremonies were unveiled in January 2022.[34] The uniforms have been designed in a joint project by the Central Academy of Fine Arts and Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology.[34]

Torch relay

[edit]

The torch relay started on 18 October 2021 in Greece. On 20 October 2021, it was announced that the local leg would start on 2 February and end on 4 February 2022 during the Opening Ceremonies. The local leg only visited two cities: Beijing and Zhangjiakou.[35] Activists staged a protest at the Olympic torch lighting ceremony in Greece.[36]

The inclusion and television appearance of Qi Fabao, a People's Liberation Army commander well known in China for his involvement in the 2020–2021 China–India skirmishes, as one of 1,200 torchbearers have been controversial, with India launching a diplomatic boycott of the Games as a result.[37]

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

[edit]

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in changes in the qualifying process for curling and women's ice hockey due to the cancellation of tournaments in 2020. Qualification for curling was based on placement in the 2021 World Curling Championships and an Olympic Qualification Event that completed the field (in place of points earned across the 2020 and 2021 World Curling Championships). The IIHF based its qualification for the women's tournament upon existing IIHF World Rankings, without holding the 2020 Women's World Championship.[38][39]

On 29 September 2021, the IOC announced biosecurity protocols for the Games; all athletes were required to remain within the bio-secure bubble (referred to as a "closed-loop management system") for the duration of their participation, which included daily COVID-19 testing, and only being allowed to travel to and from Games-related venues. Unless they are fully-vaccinated or have a valid medical exemption, all athletes were required to quarantine for 21 days upon their arrival. Mirroring a protocol adopted for the 2020 Summer Olympics before they were moved behind closed doors, the IOC also announced that only residents of the People's Republic of China would be permitted to attend the Games as spectators.[40][41]

On 23 December 2021, the United States' National Hockey League (NHL) and its labor union, the National Hockey League Players' Association (NHLPA), announced that they had agreed to withdraw their players' participation in the Games' men's hockey tournament, citing concerns over COVID-19 and the need to make up games that had been postponed due to COVID-19 outbreak[42] As part of their latest collective agreement with the NHLPA, the NHL had agreed to accommodate a break for the Olympics and player participation for the first time since 2014.[43]

On 17 January 2022, amid increasing lockdowns across China and the first detected case of the Omicron variant in Beijing, it was announced that ticket sales to the general public were cancelled, and that limited numbers of spectators would be admitted by invitation only. These, therefore, became the second Olympics in a row that were closed to the general public.[44] In the lead-up to the Games, organizers stated that they had aimed for at least 30% capacity at each venue, divided equally between spectators from within the "closed loop" (including dignitaries, delegations, and the press), and invited guests from outside of it (including local residents, school students, winter sports enthusiasts, and marketing partners). At least 150,000 spectators from outside the "closed loop" were expected to attend. Spectators were only present at events held in Beijing and Zhangjiakou; all events in Yanqing were held behind closed doors with no spectators permitted.[45][46]

Everyone present at the Games, including athletes, staff, and attendees, were required to use the My2022 mobile app as part of the biosecurity protocols, which was used for submissions of customs declarations and health records for travel to the Games, daily health self-reporting, and records of COVID-19 vaccination and testing. The app also provided news and information relating to the Games, and messaging functions. Concerns were raised about the security of the My2022 app and how information collected by it would be used, so several delegations advised their athletes to bring burner phones and laptops for the duration of the games.[47][48]

Because of the strict COVID-19 protocol, some top athletes, considered to be medal contenders, were not able to travel to China after having tested positive, even if asymptomatic. The cases included Austrian ski jumper Marita Kramer, the leader of the World Cup ranking,[49] and Russian skeletonist Nikita Tregubov, silver medalist of the 2018 Winter Olympics.[50]

Transportation

[edit]

The new Beijing–Zhangjiakou intercity railway opened in late 2019, starting from Beijing North railway station and ending at Zhangjiakou railway station. It was built for speeds of up to 350 km/h (220 mph); with this new road system, the travel time from Beijing to Zhangjiakou was decreased to around 50 minutes. A dedicated train for the Winter Olympics began to run on this line in January 2022, featuring a mobile television studio that supports live broadcast on the train.[51]

On 31 December 2021, the Beijing Subway reached the planned 783 km (487 mi) at the bid book.[52]

Planned before the city was awarded the rights to the Games, the Beijing Daxing International Airport opened in 2019, and due to the strategic location, it would be the main focus for the arrival and entry of delegations on Chinese soil. Chinese officials had hoped that this airport would replace Beijing Capital International Airport as the country's main hub for arrivals and departures between its opening and the Winter Games and reduce the international and domestic demands of the older airport. This airport replaced the old Beijing Nanyuan Airport which was out of date and was on the list of the most dangerous airports in the world because of its location and since its opening, it has been sharing the local and international demands of the city and the country with the older Beijing Capital International Airport.[53] However, according to the COVID-19 pandemic security protocol manual issued by BOCWOG and International Olympic Committee, all foreign delegations could only enter and leave Beijing via the Capital International Airport due to its smaller size and the fact that it is closer to the city center and Olympic Green and has specific isolation areas and a better health protocols.[54]

Budget

[edit]The original estimated budget for the Games was US$3.9 billion, less than one-tenth of the $43 billion spent on the 2008 Summer Olympics.[55] Although there were reports that the games might cost more than US$38.5 billion,[56] the final official budget was US$2.24 billion and turning a profit of $52 million, of which the International Olympic Committee (IOC) donated $10.4 million of that surplus to the Chinese Olympic Committee (COC) to help with the development of sport in China.[57][58]

Ceremonies

[edit]Opening ceremony

[edit]

The opening ceremony of the 2022 Winter Olympics was held on 4 February 2022 at Beijing National Stadium.

Amid the political controversies and tensions impacting the Games, IOC president Thomas Bach instructed athletes to "show how the world would look like, if we all respect the same rules and each other", and pledged that "there [would] be no discrimination for any reason whatsoever."[59]

The final seven torchbearers reflected multiple decades of Chinese athletes, beginning with the 1950s, and concluding with two skiers competing in the Games—21 year-old skier Zhao Jiawen from Shanxi (the first Chinese athlete to compete in Nordic combined), and 20-year-old Dinigeer Yilamujiang from the Xinjiang autonomous region (cross-country, and the first Chinese cross-country skier to win a medal in an ISF event).[60][61]

For the first time in Olympic history, the final torchbearers did not light a cauldron: instead, they fitted the torch into the centre of a large stylised snowflake, constructed from placards bearing the names of the delegations competing in the Games.[61] Three similar snowflakes were also erected as public flames, with one outside of the stadium lit by a volunteer, one in Yanqing District lit by speed skater Yu Jongjun, and the third in Zhangjiakou lit by skier Wang Wezhuo.[60]

Closing ceremony

[edit]The closing ceremony of the 2022 Winter Olympics was held at Beijing National Stadium on 20 February 2022; it included a cultural presentation, closing remarks, and the formal handover to Milan and Cortina d'Ampezzo as hosts of the 2026 Winter Olympics.[62]

Sports

[edit]The 2022 Winter Olympics included a record 109 events over 15 disciplines in seven sports.[63] There are seven new medal events, including men's and women's big air freestyle, women's monobob, mixed team competitions in freestyle skiing aerials, ski jumping, and snowboard cross, and the mixed relay in short track speed skating.[64]

Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of medal events contested in each discipline.

Alpine skiing (11) ()

Alpine skiing (11) () Biathlon (11) ()

Biathlon (11) () Bobsleigh (4) ()

Bobsleigh (4) () Cross-country skiing (12) ()

Cross-country skiing (12) () Curling (3) ()

Curling (3) () Figure skating (5) ()

Figure skating (5) () Freestyle skiing (13) ()

Freestyle skiing (13) () Ice hockey (2) ()

Ice hockey (2) () Luge (4) ()

Luge (4) () Nordic combined (3) ()

Nordic combined (3) () Short track speed skating (9) ()

Short track speed skating (9) () Skeleton (2) ()

Skeleton (2) () Ski jumping (5) ()

Ski jumping (5) () Snowboarding (11) ()

Snowboarding (11) () Speed skating (14) ()

Speed skating (14) ()

New events

[edit]In October 2016, the International Ski Federation (FIS) announced plans to begin permitting women's competitions in Nordic combined, to contest the discipline at the Olympic level for the first time in Beijing.[65] In November 2017, a further three events were put forward by the FIS for possible Olympic inclusion: a ski jumping mixed team competition and men's and women's big air in freestyle skiing.[66] At their May 2018 Congress at the Costa Navarino resort in Messenia, Greece, the FIS submitted several additional events for consideration, including a proposal to make telemark skiing an Olympic discipline for the first time in Beijing, with proposed competitions to include the men's and women's parallel sprint and a mixed team parallel sprint. The Congress also approved to submit the aerials mixed team event, and several new snowboarding events: the men and women's snowboard cross team event; a mixed team alpine parallel event; the men's and women's parallel special slalom; and a mixed team parallel special slalom event.[67] The individual parallel special slalom events were featured at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia, but were dropped from the Olympic program in 2018 to make way for the snowboarding big air competitions.[citation needed]

The International Luge Federation (FIL) proposed the addition of six new events, including natural track luge (men's and women's singles), a women's doubles competition on the artificial track, and sprint events (men, women, and doubles) on the artificial track.[68][69]

The International Skating Union (ISU) continued to campaign for the addition of synchronized skating as a new event within the discipline of figure skating.[70] The ISU also proposed a new mixed team event in short track speed skating.[68]

In biathlon, a single mixed relay was proposed by the International Biathlon Union (IBU) to complement the four-person mixed relay that featured at the 2018 Winter Olympics.[68] Also, the International Bobsleigh and Skeleton Federation (IBSF) proposed a new team event, but there was no plan to introduce a four-woman bobsleigh event despite the recommendation from the federation's executive board to propose such an event in the interests of gender equality.[68]

In July 2018, the IOC announced changes to the program for the 2022 Winter Olympics as part of a goal to increase the participation of women, and appeal to younger audiences. Seven new medal events were added (expanding the total program to 109 events), including men's and women's big air freestyle, women's monobob, mixed team competitions in freestyle skiing aerials, ski jumping, and snowboard cross, and the mixed relay in short track speed skating.[71] Women's Nordic combined was not added; Nordic combined remains the only Winter Olympic sport only contested by men.[72]

Participating National Olympic Committees

[edit]On 9 December 2019, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) banned Russia from all international sport for four years, after the Russian government was found to have tampered with lab data that it provided to WADA in January 2019 as a condition of the Russian Anti-Doping Agency being reinstated. As a result of the ban, WADA planned to allow individually cleared Russian athletes to take part in the 2020 Summer Olympics under a neutral banner, as instigated at the 2018 Winter Olympics, but they were not permitted to compete in team sports. WADA Compliance Review Committee head Jonathan Taylor stated that the IOC would not be able to use "Olympic Athletes from Russia" (OAR) again, as it did in 2018, emphasizing that neutral athletes cannot be portrayed as representing a specific country.[73][74][75] Russia later filed an appeal to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) against the WADA decision.[76]

After reviewing the case on appeal, CAS ruled on 17 December 2020 to reduce the penalty WADA had placed on Russia. Instead of banning Russia from sporting events, the ruling allowed Russia to participate in the Olympics and other international events, but for two years, the team cannot use the Russian name, flag, or anthem and must present themselves as "Neutral Athlete" or "Neutral Team." The ruling does allow for team uniforms to display "Russia" on the uniform as well as the use of the Russian flag colors within the uniform's design, although the name should be up to equal predominance as the "Neutral Athlete/Team" designation.[77]

On 19 February 2021, it was announced that Russia would compete under the acronym "ROC" after the name of the Russian Olympic Committee although the name of the committee itself in full could not be used to refer to the delegation. Russia would be represented by the flag of the Russian Olympic Committee.[78]

On 8 September 2021, the IOC Executive Board suspended the Olympic Committee of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) through at least the end of 2022 for violations of the Olympic Charter, over its refusal to send athletes to the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo due to COVID-19 pandemic-related concerns. North Korean athletes would be allowed to participate under the Olympic flag.[79][80][81][82] However, North Korean Ministry of Sports and the National Olympic Committee said in a letter to the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics Organizing Committee, the Chinese Olympic Committee, and the General Administration of Sport of China on 7 January 2022 that "Due to the "action of hostile forces" and the COVID-19 pandemic, they would not be able to participate in the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics."[83] In addition, the North Korean Olympic Committee said "supports all the work of our comrades in China to host a grand and wonderful Olympics. The United States and its followers are plotting anti-Chinese conspiracies to obstruct the successful hosting of the Olympics, but this is an insult to the spirit of the Olympic Charter and an act to damage China's international image. We firmly oppose and reject these actions."[84]

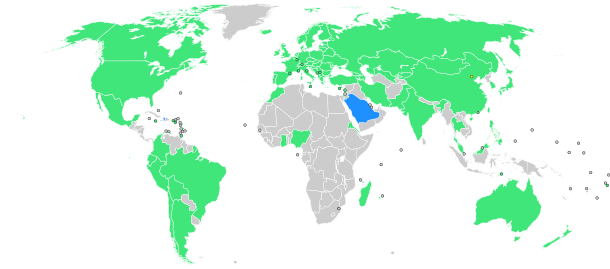

The following 91 National Olympic Committees have qualified athletes (two fewer than four years earlier), with Haiti and Saudi Arabia making their Winter Olympic débuts.[85][86] Kenya qualified one athlete, but withdrew.[87]

Number of athletes by National Olympic Committee

[edit]Calendar

[edit]Competition began two days before the opening ceremony on 2 February, and ended on 20 February 2022.[182] Organizers went through several revisions of the schedule, and each edition needed to be approved by the IOC.[183]

- All times and dates use China Standard Time (UTC+8)

| OC | Opening ceremony | ● | Event competitions | 1 | Event finals | EG | Exhibition gala | CC | Closing ceremony |

| February 2022 | 2nd Wed | 3rd Thu | 4th Fri | 5th Sat | 6th Sun | 7th Mon | 8th Tue | 9th Wed | 10th Thu | 11th Fri | 12th Sat | 13th Sun | 14th Mon | 15th Tue | 16th Wed | 17th Thu | 18th Fri | 19th Sat | 20th Sun | Events | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OC | CC | — | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 | |||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 11 | ||||||||||||

| ● | 1 | 1 | ● | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 12 | |||||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 1 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| ● | ● | 1 | ● | 1 | ● | 1 | ● | 1 | ● | 1 | EG | 5 | |||||||||

| ● | 1 | 1 | ● | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 13 | ||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 1 | ● | ● | 1 | 2 | |||

| ● | 1 | ● | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 9 | |||||||||||||||

| ● | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | ● | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||||||||

| ● | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ● | 2 | 11 | |||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 14 | |||||||||

| Daily medal events | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 109 | |

| Cumulative total | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 12 | 21 | 31 | 37 | 45 | 52 | 58 | 65 | 69 | 78 | 86 | 92 | 97 | 104 | 109 | ||

| February 2022 | 2nd Wed | 3rd Thu | 4th Fri | 5th Sat | 6th Sun | 7th Mon | 8th Tue | 9th Wed | 10th Thu | 11th Fri | 12th Sat | 13th Sun | 14th Mon | 15th Tue | 16th Wed | 17th Thu | 18th Fri | 19th Sat | 20th Sun | Total events | |

Medal table

[edit]

Norway finished at the top of the medal table for the second successive Winter Olympics, winning a total of 37 medals, of which 16 were gold, setting a new record for the largest number of gold medals won at a single Winter Olympics.[4] Germany finished second with 12 golds and 27 medals overall. United States finished third with 9 golds and 25 medals overall, and the host nation China finished fourth with nine gold medals, marking their most successful performance in Winter Olympics history.[4] The team representing the ROC ended up with the second largest number of medals won at the Games, with 32, but finished ninth on the medal table, as only five gold medals were won by the delegation. Traditional Winter powerhouse Canada; despite having won 26 medals, only four of them were gold, resulting in a finish outside the top ten in the medal table for the first time since 1988 (34 years).[184][185]

* Host nation (China)

| Rank | NOC | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | 8 | 13 | 37 | |

| 2 | 12 | 10 | 5 | 27 | |

| 3 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 25 | |

| 4 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 15 | |

| 5 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 18 | |

| 6 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 17 | |

| 7 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 18 | |

| 8 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 15 | |

| 9 | 5 | 12 | 15 | 32 | |

| 10 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 14 | |

| 11–29 | Remaining | 23 | 40 | 47 | 110 |

| Totals (29 entries) | 109 | 109 | 110 | 328 | |

Podium sweeps

[edit]| Date | Sport | Event | Team | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 February | Bobsleigh | Two-man bob | Francesco Friedrich Thorsten Margis | Johannes Lochner Florian Bauer | Christoph Hafer Matthias Sommer | [187] |

Changes in medal standings

[edit]On 29 January 2024, CAS disqualified Kamila Valieva for four years retroactive to 25 December 2021 for an anti-doping rule violation.[188] On 30 January 2024, the ISU reallocated medals in the figure skating team event to upgrade the United States to gold and Japan to silver while downgrading ROC to bronze.[189]

Marketing

[edit]Emblem

[edit]

The emblem for the 2022 Winter Olympics, "Winter Dream" (冬梦), was unveiled on 15 December 2017 at the Beijing National Aquatics Center. Designed by Lin Cunzhen (who previously designed the emblem of the 2014 Summer Youth Olympics in Nanjing), the emblem is a stylised rendition of the Chinese character for winter (冬) as a multi-coloured ribbon, reflecting upon the landscapes of the host region. The beginning of the ribbon symbolizes an ice skater, while the end of the ribbon symbolizes a skier. The emblem carries a blue, red, and yellow colour scheme: the latter two colours represent both the flag of China, and "passion, youth, and vitality".[190]

Mascot

[edit]Bing Dwen Dwen was the mascot of the 2022 Winter Olympics. Bing Dwen Dwen was chosen from thousands of Chinese designs in 35 countries worldwide. "Bing" (冰) means ice in Chinese, and was meant to suggest purity and strength. "Dwen Dwen" (墩墩) was meant to suggest robustness, liveliness, and youth. Bing Dwen Dwen's astronaut-like clothes implied that the Winter Olympics embraced new technologies and created possibilities.[191]

Slogan

[edit]The Games' official slogan, "Together for a Shared Future" (Chinese: 一起向未来; pinyin: Yīqǐ xiàng wèilái), was announced on 17 September 2021; organisers stated that the slogan was intended to reflect "the power of the Games to overcome global challenges as a community".[192]

The slogan was compared in media with Chinese leader Xi Jinping's policy slogan: 'Building the Common Future of Humanity'.[193]

Viewership

[edit]- Independent research conducted on behalf of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) recorded 2.01 billion viewers across television and digital platforms.[194][195]

- A total of 713 billion minutes of coverage was watched on various Olympic Media Rights Partners' channels, which represents an 18 per cent increase when comparing with the last Winter Olympics.[194]

Broadcasting

[edit]In China, domestic rights to these Games were owned by China Media Group (CMG), with rights being sublicensed by China Mobile's Migu streaming service.[196] In some countries, broadcast rights to the 2022 Winter Olympics were already agreed upon through existing long-term deals. In France and the United Kingdom, these were the first Games where Eurosport would be the main rightsholder; the BBC sub-licensed a limited amount of coverage on free-to-air television, as part of a deal in which the BBC sold the pay-TV rights to the 2018 and 2020 Games to Eurosport.[197][198] In January 2022, the BBC announced it would broadcast over 300 hours of free-to-air live coverage, as well as highlights programmes.[199][200]

The scheduling of the Games impacted the U.S. broadcast rights to the Super Bowl—the championship game of the National Football League (NFL), and historically the most-watched television broadcast in the United States annually—as the game's date fell within an ongoing Olympic Games for the first time in its history. Under the NFL's broadcast rights at the time, the rights to the Super Bowl alternated annually between CBS, Fox, and long-time Olympic broadcaster NBC (whose last Super Bowl also fell in a Winter Olympic year, but was held prior to the opening ceremony).[201] To prevent the Games from competing for viewership and advertising sales with Super Bowl LVI—which was scheduled for 13 February 2022 at Los Angeles' SoFi Stadium—CBS and NBC announced in March 2019 that they would invert the rights for Super Bowl LVI and LV (2021), so that both the 2022 Winter Olympics and Super Bowl LVI would be broadcast by NBC.[202][203] In a break from the established practice of airing premieres or special episodes of entertainment programmes after the Super Bowl to take advantage of its large audience, NBC aired its prime time coverage for Day 10 of the Games immediately following Super Bowl LVI.[204] Furthermore, the NFL's new media rights beginning in 2023 extends the Super Bowl rotation to four networks by adding ABC and ESPN, thus codifying this scenario by giving NBC rights to the Super Bowl in 2026, 2030, and 2034, all of which are Winter Olympic years.[205][206]

These Games also confirmed an ongoing trend in U.S. viewership of the Olympics; while television viewership had seen a further decline, they were offset by increases in social media engagement and streaming viewership of the Games. Similar trends were seen in Europe, where amidst falling TV ratings Eurosport reported an eight-fold increase in streaming viewership on its platforms and Discovery+ over Pyeongchang 2018.[207][208][209]

Concerns and controversies

[edit]

During the bidding process, critics questioned the Beijing bid, arguing that the proposed outdoor venue sites do not have reliable snowfall in winter for snow sports. Concerns have been raised that snow may need to be transported to the venues at great cost and with uncertain environmental consequences.[210][211]

Additional concerns about weather conditions were raised during certain events. Swedish athlete Frida Karlsson nearly collapsed after the women's skiathlon due to low temperatures.[212] Afterwards, the Swedes considered putting in a request for races to be moved to earlier in the day, stating that the afternoons and early evenings scheduled for European TV audiences were hurting the performance of the athletes.[213]

As in 2008, activists, human rights groups, and diplomats made calls to boycott the Olympic Games when hosted by China. In the aftermath of the 2019 leak of the Xinjiang papers, the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests, and the persecution of Uyghurs in China,[214][215] calls were made for a boycott of the 2022 Games.[216][217][218] Because of these issues, the selection of an athlete from Xinjiang as part of the final torchbearers received a mixed reaction.[219][220][61]

In February 2021, the Chinese Communist Party-owned tabloid Global Times warned that China could "seriously sanction any country that follows a boycott."[221][222] In March 2021, Chinese spokesperson Guo Weimin stated that any attempt to boycott the Olympics would be doomed to fail.[223] China's Foreign Minister Wang Yi also told the EU's foreign policy chief Josep Borrell that they should attend the games to "enhance exchanges on winter sport", and to "foster new highlights" in bilateral cooperation.[224]

The IOC stated that it remains neutral in all global political issues and that the award of hosting the games does not signal agreement with the host country's political or social situation or its human rights standards. The committee's response to Agence France-Presse read: "We've repeatedly said it: the IOC isn't responsible for the government. It only gives the rights and opportunity for the staging of the Olympic Games. That doesn't mean we agree with all the politics, all the social or human rights issues in the country. And it doesn't mean we approve of all the human rights violations of a person or people." The statement attracted criticism, with Pacific University professor Jules Boykoff accusing the IOC of "hypocrisy".[224]

On 19 November 2021, a group of 17 members of the Lithuanian national parliament Seimas released an official letter encouraging Lithuania to withdraw from the 2022 Winter Olympics due to human rights violations in China.[225] On 3 December 2021, Lithuania was the first nation to announce a diplomatic boycott of the games.[226]

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022, The New York Times published a report alleging that China requested Russia to delay the invasion until after the Olympics to avoid damaging the Games' public image.[227] Russia invaded Ukraine just four days after the Games' Closing Ceremony. Liu Pengyu, spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy in Washington, has rejected the claims as "speculations without any basis, and intended to blame-shift and smear China".[228]

American diplomatic boycott

[edit]The United States boycott of China's Winter Olympics was predominantly due to China's human rights issues on topics such as the systematic oppression of the Uyghurs, Tibetans and the riots in Hong Kong in 2019.[229] The Chinese government implemented many coercive activities in those regions, such as the reeducation camps, mass detention camps, and restricted access to social media.

Key event timeline

[edit]In October 2018, American senator Marco Rubio, Senator Jeff Merkley, and Congressmen Jim McGovern and Chris Smith sent a letter, on behalf of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC), to the International Olympic Committee (IOC) requesting the revocation of China's host right on the 2022 Winter Olympics.[230] The letter stated that "no Olympics should be held in a country whose government is committing genocide and crimes against humanity."

In November 2021, President Biden proposed "a diplomatic boycott of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics."[231] The United States was aware of the prospective harsh punishment of being suspended by the National Olympic Committee and was careful regarding the scale and severity of the boycott.[231]

In December 2021, the Biden administration officially initiated a diplomatic boycott of the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, restricting United States government officials' presence at the games.[232] The attendance of Team USA athletes was not affected by the diplomatic boycott.

Reactions

[edit]The IOC remained relatively neutral regarding the letter from CECC or the boycott.[233] The IOC negotiated with the Chinese government on specific protocols to ensure the Olympic Games ran smoothly, such as providing unrestricted internet access to foreign journalists.[231]

From China's perspective, the United States was "politicizing sports" with the Biden Boycott of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics.[234] The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson, Zhao Lijian, accused the United States of violating the spirit of political neutrality endorsed in the Olympic Charter, emphasizing that an Olympic game should not be a place for political posturing and manipulation.[235] China announced that the United States was not yet officially invited by the host committee; thus, the United States should not have initiated the boycott in the first place.[236]

Following the United States, many countries in the Western world decided to join the diplomatic boycott to show disapproval of China's human rights issues.[231]

Environmental impact

[edit]An estimated 49 million US gallons (190,000,000 L; 41,000,000 imp gal) of water was expected to be used to create snow at the various venues. Pyeongchang, South Korea, which held the previous Winter Olympics, also had a cold but similarly arid climate that required vast quantities of artificial snow. Professor Carmen de Jong, a geographer at the University of Strasbourg, argued that these would be the "most unsustainable" Winter Olympics in history. The IOC stated that "a series of water-conserving and recycling designs have been put into place to optimize water usage for snowmaking, human consumption, and other purposes.[237][needs update]

Artificial snow forms a harder piste compared to real snow. It is often favoured by professionals for being fast and "hyper-grippy" but also raises their fear of falling on it.[237][238] American snowboarder Jamie Anderson compared it to "pretty bulletproof ice" while her teammate Courtney Rummel compared it to the man-made snow in Wisconsin.[238]

According to Jules Boykoff in February 2022, Beijing's electricity came largely from coal and this coal power was what supported the construction of some Olympic venues. To offset emissions from construction and air travel, China had planted roughly 60 million trees.[239]

Sporting controversies

[edit]There were concerns about decisions and disqualification in several events during the games. These issues included the following:

- An official appeal to the Court of Arbitration for Sport over the disqualification of two South Korean athletes from the men's 1000 metres short track speed skating event filed by the Korean Sport & Olympic Committee, after having their protests rejected by the International Skating Union.[240][241][242]

- Controversy surrounding a ruling of an obstruction in the 5000 metres relay event.[243]

- A potential missed call by judges during the men's snowboard slopestyle and men's half pipe event events.[244][245][246][247]

- A ruling of a false start in the men's 500 metres speed skating event.[248]

- The disqualification of racers for their uniforms during the mixed team normal hill event of ski jumping.

- The continued participation of the figure skater Kamila Valieva in the women's singles competition after a preliminary positive drug test from a sample 2 months prior.[249]

- Three athletes failed the doping test during the Olympics and were suspended: Iranian alpine skier Hossein Saveh-Shemshaki, Ukrainian cross-country skier Valiantsina Kaminskaya, and Ukrainian bobsledder Lidiia Hunko.[250] The positive test of the Spanish figure skater Laura Barquero was announced after the Olympics.[251][252]

- U.S. skater Joey Mantia alleged that South Korean skater Lee Seung-hoon made contact with him and pulled him back, preventing him from winning a bronze medal in the Mass Start final. Mantia lost by a 0.002-second margin. Team USA challenged the result, but Lee was awarded the bronze medal.[253][254][255]

Athlete and officials complaints

[edit]The food and overall conditions in quarantine hotels given to athletes testing positive for COVID-19 were criticised early on.[256][257] Team officials from delegations including Belgium, Germany, Poland, Finland and the Russian Olympic Committee all brought up issues their athletes faced in quarantine hotels, among them were the lack of internet connections, low-quality food, insufficient facilities and no training equipment.[258][259][260]

With China's Zero-COVID policy, there were issues raised about the process of quarantine at the games.[256] On 2 February, Belgian skeleton athlete Kim Meylemans posted on social media and was in tears about the conditions she faced while in quarantine.[261][262] According to Newsweek and Time, the hotels' conditions appeared to have improved after the athletes' complaints were made public.[257][263]

There were some complaints about the food served outside of quarantine. Germany's alpine coach Christian Schweiger called the catering "extremely questionable" for not having hot meals but he echoed athletes from several nations that the food at the nearby Athletes' Village was great.[264] The US and South Korean teams elected to bring their own food.[265] Austrian skier Matthias Mayer said that Kitzbuehel would have offered "the best of the best" but also that a hot meal right before a race might not bring out top performances.[264][266]

Other complaints included low temperatures and related safety concerns. Sweden's Frida Karlsson nearly collapsed at the conclusion of the women's skiathlon cross-country race. Afterwards, her team considered requesting that races held in afternoons and evenings for European TV audiences be moved to earlier during the day.[213][212] Some athletes resorted to putting tape on their faces and noses to protect them from the bitter cold.[267] Heavy snowfall disrupted a number of competition and training events on 13 February. Thirty-three skiers did not finish their first run of the men's giant slalom. Henrik Kristoffersen of Norway said that he "couldn't see shit." Switzerland's Loic Meillard said, "It's not what I was hoping for but it's part of the game ... we've raced in conditions like that before."[268]

See also

[edit]- 2022 Winter Paralympics

- Olympic Games held in China

- 2008 Summer Olympics – Beijing

- 2014 Summer Youth Olympics – Nanjing

- 2022 Winter Olympics – Beijing

Notes

[edit]- ^ Xi Jinping is current China's nominal head of state, serving as Chinese president. Xi is also the general secretary of the Communist Party, the most powerful position in China, serving as the paramount leader of China.

- ^ Neutral athletes from Russia competed under the flag of the Russian Olympic Committee.

- ^ NOC suspended.

References

[edit]- ^ "SuperSport". supersport.com (in Zhuang). Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Reyes, Yacob (8 December 2021). "Beijing Olympics: These countries have announced diplomatic boycotts". Axios. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ Allen-Ebrahimian, Bethany; Baker, Kendall (1 February 2022). "The IOC stays silent on human rights in China". Axios. Archived from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Church, Ben (20 February 2022). "Norway tops Beijing 2022 medal table after record-breaking performance". CNN. Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ McNicol, Homero De la Fuente, Andrew (30 January 2024). "US figure skaters awarded Olympic gold, Canada snubbed from bronze after Russian skater disqualified". CNN. Archived from the original on 30 January 2024. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "U.S. figure skaters to get Olympic team event gold after Kamila Valiyeva DQ". NBC Sports. 30 January 2024. Archived from the original on 31 January 2024. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ "Host City Election". International Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ Wilson, Stephen (7 July 2014). "Almaty, Beijing, Oslo make list for 2022 Olympics". New York City, New York, U.S. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Abend, Lisa (3 October 2014). "Why Nobody Wants to Host the 2022 Winter Olympics". Time. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ "IOC hits out as Norway withdraws Winter Olympic bid". The Financial Times. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ "Winter Olympics: What now for 2022 after Norway pulls out?". BBC Sport. 2 October 2014. Archived from the original on 5 May 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Mathis-Lilley, Ben (2 October 2014). "The IOC Demands That Helped Push Norway Out of Winter Olympic Bidding Are Hilarious". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ "IOC reportedly made some ridiculous demands to help push Oslo out of 2022 Winter Olympics bidding". National Post. 2 October 2014. Archived from the original on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ "IOC krever gratis sprit på stadion og cocktail-fest med Kongen". October 2014. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Oslo 2022 bid hurt by IOC demands, arrogance". Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ Yin, Ivy; Yep, Eric (11 February 2022). "Winter Olympics 2022 is the 'carbon neutral template' for future global events". S&P Global Platts. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Beijing intends to run the Olympic games next year on purely green energy". Indus Tribune. 28 February 2021. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ Omatiga, Mary (13 February 2022). "2022 Winter Olympics: Everything you need to know about the Beijing Winter Olympics". OlympicTalk | NBC Sports. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Beijing 2022 Venue Guide: Beijing Zone". Team Canada - Official Olympic Team Website. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ Morgan, Liam (12 June 2017). "Beijing 2022 Coordination Commission chair praises plans for snowboard big air after venue visit". Inside the Games. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ^ "北京冬奥村不出售 赛后成人才公租房". Beijing2022.cn. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ Mullin, Eric (15 February 2022). "Here's Where the Closing Ceremony Is Being Held in Beijing". NBC Bay Area. Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Coliseum (3 December 2020). "'Water Cube' revamped for Beijing 2022". Coliseum. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "Explainer: Water Cube where Phelps ruled turns into Ice Cube". AP NEWS. 3 February 2022. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "Big Air Shougang set to host ski jumping at Beijing Winter Olympics". Dezeen. 3 February 2022. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "五棵松体育中心_北京2022年冬奥会_新华网". www.news.cn. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ world, STIR. "A look at the stadiums hosting the Olympic Games Beijing 2022". www.stirworld.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ "A look at the venues for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics - Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ Originally simply Zhuangke. It is said that the village Dazhuangke has been officially renamed Xidazhuangke/West Dazhuangke to avoid confusion with the other Dazhuangke, also in Yanqing District. Zhuangke (庄窠) approximately means peasant dwellings/households in certain dialects of Jin Chinese; Zhuangke (庄科) is a Mandarin corruption of Jin Chinese Zhuangke (庄窠).

- ^ Phillips, Tom (31 July 2015). "Beijing promises to overcome lack of snow for 2022 Winter Olympics". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 June 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Mills, Chris (1 August 2015). "Here's the 2022 Winter Olympics Venue, In The Middle of Winter". Archived from the original on 2 August 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ gaiazhang. "Beijing 2022 Games Ski Venue Receives Over 2 Million Tourists". Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Beijing 2022 Olympic medals design unveiled with 100 days to go". Beijing2022.cn. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ a b Barker, Philip (2 January 2022). "Beijing 2022 reveals uniforms for medal ceremonies heavily influenced by snow". InsideTheGames.biz. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Beijing 2022 welcomes Olympic flame to China". Beijing2022.cn. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ O'Donnell, Noreen (28 January 2022). "Uyghurs, Tibetans, Hong Kongers Join Together to Protest Beijing Olympics". nbcchicago.com. NBC Chicago. Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ Ramachandran, Sudha. "India Joins Diplomatic Boycott of Beijing Winter Olympics". thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ "Curling wants 2021 world championships to determine qualifying for Beijing Olympics". CBC Sports. 9 April 2020. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ "U.S., Canada in same 2022 Olympic hockey group". NBC Sports. 24 April 2020. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ Gan, Nectar (30 September 2021). "Beijing Winter Olympics will be open to fans – if they live in China". CNN. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "Overseas fans banned from 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics". Aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "NHL will not send players to Beijing". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ "NHL players to participate in '22 Beijing Olympics". ESPN.com. 3 September 2021. Archived from the original on 10 September 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ "Beijing 2022 tickets will not be sold to general public due to COVID-19 concerns". Inside the Games. 17 January 2022. Archived from the original on 17 January 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "Beijing Olympics organizers hope to have 30% capacity in venues". Nikkei Asia. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ "Beijing 2022 expect 150,000 spectators from outside closed loop to attend events". www.insidethegames.biz. 3 February 2022. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ "Winter Olympics: Athletes advised to use burner phones in Beijing". BBC News. 18 January 2022. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ Schad, Tom. "Olympic burner phones? Athletes warned about bringing personal devices to China for 2022 Beijing Games". USA Today. Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ "Skispringster Kramer, favoriet voor goud, mist Spelen door coronabesmetting". NOS (in Dutch). 1 February 2022. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ "Skeleton medalist out of Beijing Olympics with virus". Associated Press. 31 January 2022. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ "记者揭秘:冬奥列车高铁5G超高清演播室有啥新科技?" (in Chinese). China Central Television. 6 January 2022. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "官宣!北京9段新地铁今天开通!线路图、新站抢先看". Ie.bjd.com.cn. 31 December 2021. Archived from the original on 30 December 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ^ "New Beijing airport to open on Oct 1, 2019, able to accommodate 620,000 flights per year". The Straits Times. 17 May 2018. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "北京2022年冬奥会和冬残奥会运动员和随队官员防疫手册(第二版)" (PDF). Beijing Organizing Committee for the 2022 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games. 13 December 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Beijing won't have a big budget for the 2022 Winter Olympics". CNNMoney. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "Beijing 2022 may cost more than US$38.5bn, says report". SportsPro. 1 February 2022. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "Beijing Olympics Report $52 Million Profit, IOC To Donate $10.4 To Chinese Sport". Boxscore World Sportswire. 6 May 2023. Archived from the original on 18 May 2023. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ "IOC donates its $10.4m share of $52m Beijing 2022 surplus to Chinese sport". www.insidethegames.biz. 6 May 2023. Archived from the original on 30 May 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ "2022 Winter Olympics officially begin". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Uyghur athlete lights Olympic Cauldron as Beijing 2022 officially opens". Inside the Games. 4 February 2022. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Chappell, Bill (4 February 2022). "The Beijing Winter Olympics' cauldron lighting made a political statement". NPR. Archived from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ Carpenter, Les (2 December 2021). "The Beijing Olympics begin Feb. 4. Here's what you need to know". The Washington Post. Washington D.C, United States of America. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "Athletes to compete in 109 events of 7 sports at Beijing Winter Olympics". Helsinki Times. Helsinki, Finland. 18 December 2021. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Zaccardi, Nick (18 July 2018). "Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics add seven new events". Olympics.nbcsports.com/. NBC. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ "FIS target Nordic Combined women's competition at Beijing 2022". 3 October 2016. Archived from the original on 9 December 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ "FIS Council Decisions from Autumn 2017 Meeting". fis-ski.com/. FIS. 18 November 2017. Archived from the original on 16 December 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "FIS propose telemark skiing for Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics". Insidethegames.biz. 18 May 2018. Archived from the original on 20 May 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d Butler, Nick (5 March 2018). "Exclusive: Women's Nordic combined and synchronised skating among new disciplines proposed for Beijing 2022". insidethegames.biz. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ "FIL submits full package of events for Olympic bid". fil-luge.org/. FIL. 31 October 2017. Archived from the original on 13 September 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "Synchronized Skating has been proposed as a new "event" by the ISU". jurasynchro.com/. Jura Synchro. 9 February 2018. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ "Here's a look at the new women's, gender-balanced disciplines for the 2022 Winter Games". ESPN.com. 25 July 2018. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Latham-Coyle, Harry (4 February 2022). "What is Nordic Combined and why won't there be a women's event". The Independent. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ MacInnes, Paul (9 December 2019). "Russia banned from Tokyo Olympics and football World Cup". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ "Russia banned for four years to include 2020 Olympics and 2022 World Cup". BBC Sport. 9 December 2019. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ "WADA lawyer defends lack of blanket ban on Russia". The Japan Times. 13 December 2019. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "Russia Confirms It Will Appeal 4-Year Olympic Ban". Time. 27 December 2019. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019.

- ^ Dunbar, Graham (17 December 2020). "Russia can't use its name and flag at the next 2 Olympics". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 17 December 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ "Olympics: Russia to compete under ROC acronym in Tokyo as part of doping sanctions". Reuters. 19 February 2021. Archived from the original on 20 February 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ "IOC Executive Board suspends NOC of Democratic People's Republic of Korea". International Olympic Committee. 8 September 2021. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ "North Korea suspended from IOC after Tokyo no-show". Reuters. 8 September 2021. Archived from the original on 9 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ "North Korea suspended from IOC until end of 2022". CBC Sports. 8 September 2021. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ "North Korea banned from Beijing 2022 after IOC suspends NOC". Inside the Games. 8 September 2021. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ "North Korea, already banned from 2022 Olympics, announces it will not send team". Special Broadcasting Service. 7 January 2021. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "North Korea blames Beijing 2022 ban on "hostile forces" and criticises "vicious" US actions". Inside the Games. 7 January 2022. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "Haïti Pour La Première Fois De Son Histoire Qualifié Aux Jo D'hiver en 2022 !" [Haiti for the First Time in Its History Qualified for the Winter Olympics in 2022!]. Haitiski.com/ (in French). Haiti Ski Federation. Archived from the original on 10 December 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Pavitt, Michael (17 December 2021). "Haiti and Saudi Arabia to debut at Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics as Alpine skiers qualify". Insidethegames.biz/. Dunsar Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 17 January 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ a b Ayodi, Ayumba (18 January 2022). "Kenya withdraws from Beijing Winter Olympics". Daily Nation. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "Denni Xhepa represents Albania at the Beijing Winter Olympics". Oculus News. 17 January 2022. Archived from the original on 17 January 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ a b Burke, Patrick (23 January 2022). "American Samoa NOC commends first Winter Olympic athlete since 1994". www.insidethegames.biz/. Dunsar Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 23 January 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^