1592–1593 London plague

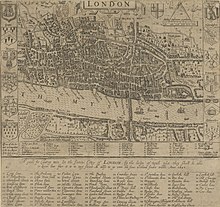

Map of London in 1576 | |

| Date | August 1592 – December 1593, with cases until 1595 |

|---|---|

| Duration | Several years |

| Location | London, Kingdom of England |

| Type | Outbreak part of the ongoing second plague pandemic since the 14th century |

| Cause | Yersinia pestis |

| Deaths | 19,900+ [1] |

From 1592 to 1593, London experienced its last major plague outbreak of the 16th century. During this period, at least 15,000 people died of plague within the City of London and another 4,900 died of plague in the surrounding parishes.[1]

London in 1592

[edit]London in 1592 was a partially-walled city of 150,000 people made of the City of London and its surrounding parishes, called liberties, just outside the walls. Queen Elizabeth I had ruled for 34 years and her government struggled with London's quickly growing population. Due to increasing economic and food shortages, disorder had grown among the underclasses in the city and beyond, whom moralist authorities increasingly struggled to govern.[2] A large and impoverished population made up the surrounding liberties, which became the first communities to be hit severely by the plague.[3]

Plague activity in England

[edit]Plague had been present in England since the Black Death, infecting various fauna in the countryside, and known as plague since the 15th century.[4] Occasionally Yersinia pestis was transmitted to human society by infectious contact with the fleas of wild animals, with disastrous results for trade, farming, and social life.[5][6]

Increasing plague activity along England's southern and eastern coasts appeared during the late 1580s and the early 1590s. An outbreak at Newcastle in 1589 killed 1727 residents by January 1590, while from 1590 to 1592 Plymouth and Devon were affected with 997 plague deaths at Totnes and Tiverton.[7]

The plague in London

[edit]

1592

[edit]London's first cases of plague were noticed in August. On 7 September, soldiers marching from England's north to embark on foreign campaigns were rerouted around the city due to concerns about infection,[1][6] and by the 21st at least 35 parishes were infected with the plague.[8] A group transporting the spoils of a Spanish carrack from Dartmouth couldn't get further than Greenwich due to the outbreak in London and news of the plague had spread regionally.[1] London's theatres, which had been temporarily closed by city authorities since a riot in June, had their shutdown orders extended to 29 December by the government.[9][10] Members of the aristocratic class sensed danger as the disease continued to spread and fled the city: "The plague is so sore that none of worth stay about these places" remarked one contemporary.[11] In November, London's College of Physicians convened a meeting to discuss the "insolent and illicit practice" of London's unlicensed medical physicians with the intention to "summon them all" before the college for quackery.[12] Queen Elizabeth's royal court also decided not to host the annual Accession Day tilt celebrations for the month due to the possibility of contagion at the royal court.[13]

Some records of the plague were copied by John Stow during his own research in the 17th century and have survived time despite the original documents being lost.[14] Around 2,000 Londoners died of plague between August 1592 and January 1593. The Company of Parish Clerks began regularly keeping and publishing records of plague mortality on 21 December 1592. Government orders forbidding performances at theatres were again extended, into 1593.[15]

1593

[edit]

Death and infection rates rose steadily during the winter months, even low temperatures often slow down flea activity during plague epidemics.[16] This was seen as ominous by Londoners observing the epidemic.[1] More resourceful, upper-class individuals continued fleeing during 1593 as the government's countermeasures proved ineffective due to the disease-harboring conditions in some areas of London. Poorer, unsanitary parishes and neighbourhoods were located near the city wall and River Thames[17] while the Fleet Ditch area of London, around Fleet Prison, became the most heavily infected part of the city. A prisoner named William Cecil (not to be confused with Lord Burghley), kept in Fleet Prison by Queen Elizabeth's command, wrote that by 6 April 1593 "The place where [William] lies is a congregation of the unwholesome smells of the town, and the season contagious, so many have died of the plague." Government letters indicated that the plague was "very hot" in London by 12 June and that the queen's royal court "was out in places, and a great part of the household is cut off."[14][11] By August Queen Elizabeth's royal court had evacuated to Windsor Castle in order to escape the increasingly dangerous outbreak in London. The city's sugar refineries continued their business unabated[11] even though public houses and theatres remained closed on government orders to halt the spread of infection.[18]

Alarm was raised at Windsor by the death of Queen Elizabeth's chambermaid Lady Scrope from plague on 21 August within the castle, which almost sent the royal court fleeing a second time.[19] But the government remained at Windsor Castle through November where Queen Elizabeth hosted her tilt celebrations.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Creighton, Charles (November 1891). A History of Epidemics in Britain: From A.D 664 to the Extinction of Plague. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 353–354.

- ^ "RIOTS AND LIBERTIES". Wesleyan University. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ Kohn, George (2008). Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: From Ancient Times to the Present. Infobase Publisher. p. 228.

- ^ Benedictow, Ole (2004). The Black Death 1345-1353: The Complete History. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-84383-214-0.

- ^ Fowler, Catherine (May 2015). Moving the Plague: the Movement of People and the Spread of Bubonic Plague in Fourteenth Century through Eighteenth Century Europe (Bachelor thesis). University of Southern Mississippi. p. 17. S2CID 126478296.

- ^ a b Scott, Susan; Duncan, Christopher (2004). Biology of Plagues: Evidence from Historical Populations. Cambridge University Press. p. 165.

- ^ Creighton, Charles (1891). A History of Epidemics in Britain: From AD 644 to the Extinction of Plague. Cambridge University Press. p. 351.

- ^ Berry, Herbert (Winter 1995). "A London Plague Bill for 1592, Crich, and Goodwyffe Hurde". English Literary Renaissance. 25. The University of Chicago Press: 12. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6757.1995.tb01425.x. S2CID 145156545 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Berry, Herbert (Winter 1995). "A London Plague Bill for 1592, Crich, and Goodwyffe Hurde". English Literary Renaissance. 25: 5. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6757.1995.tb01425.x. S2CID 145156545.

- ^ Cheney, Patrick; Cheney, Patrick Gerard; Patrick, Cheney (25 November 2004). Shakespeare, National Poet-Playwright. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-521-83923-5.

- ^ a b c Mary Anne Everett Green, ed. (1867). "Queen Elizabeth – Volume 244: February 1593". Calendar of State Papers:Elizabeth 1591-1594. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 360.

- ^ Kassell, Lauren (2005). Medicine and Magic in Elizabethan London: Simon Forman: Astrologer, Alchemist, and Physician. London: Clarendon. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-19-927905-0.

- ^ a b Strong, Roy C. (1977). The Cult of Elizabeth: Elizabethan Portraiture and Pageantry. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-520-05841-5.

- ^ a b Creighton, Charles (1891). A History of Epidemics in Britain from AD 644 to the Extinction of Plague. Cambridge University Press. pp. 352–353.

- ^ Acheson, Arthur (1920). Shakespeare's Lost Years in London 1586-1592, Giving New Light on the Pre-sonnet Period: Showing the Inception of Relations Between Shakespeare and the Earl of Southampton and Displaying John Florio as Sir John Falstaff. New York: Brentano's. pp. 85.

- ^ Kohn, George C. (2007). Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: From Ancient Times to the Present. Infobase Publishing. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-4381-2923-5.

- ^ Cummins, Neil; Kelly, Morgan; Ó Gráda, Cormac (February 2016). "Living standards and plague in London, 1560–1665" (PDF). Economic History Review. 69: 3–34. doi:10.1111/ehr.12098. S2CID 5712346 – via LSE Research Online.

- ^ "William Shakespeare". History.com. 2011.

- ^ Urban, Sylvanus (1850). The Gentleman's Magazine (London, England), Volume 187. John Nichols & Son. p. 142. Retrieved 5 May 2019.