167th (1st London) Brigade

| West London Brigade 167th (1st London) Brigade | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1888–1919 1920–1946 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry Motorised infantry |

| Size | Brigade |

| Part of | 56th (London) Division |

| Nickname(s) | "The Black Cats" (Second World War, divisional nickname) |

| Engagements | First World War Second World War |

The 167th (1st London) Brigade was an infantry formation of the British Territorial Army that saw active service in both the First and Second World Wars. It was the first Territorial formation to go overseas in 1914, garrisoned Malta, and then served with the 56th (London) Infantry Division on the Western Front. In the Second World War, it fought in the North African and Italian campaigns in the Second World War.

Origin[edit]

The Volunteer Force of part-time soldiers was created following an invasion scare in 1859, and its constituent units were progressively aligned with the Regular British Army during the later 19th Century. The Stanhope Memorandum of December 1888 introduced a Mobilisation Scheme for Volunteer units, which would assemble in their own brigades at key points in case of war. In peacetime these brigades provided a structure for collective training.[1][2]

The West London Brigade was one of the formations organised at this time. Brigade Headquarters was at 93 Cornwall Gardens in Kensington and the commander was retired Lt-Gen Lord Abinger (subsequent commanders were also retired, Regular officers). The assembly point for the brigade was at Caterham Barracks, the Brigade of Guards' depot conveniently situated for the London Defence Positions along the North Downs. The brigade's original composition was:[3]

West London Brigade

- 1st Volunteer Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

- 2nd Volunteer Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

- 3rd Middlesex Rifle Volunteer Corps

- 2nd Volunteer Battalion, Middlesex Regiment

- 11th (Railway) Middlesex Rifle Volunteer Corps

- 17th Middlesex Rifle Volunteer Corps

- Supply Detachment, Army Service Corps

- Bearer Company, Medical Staff Corps

The West London Brigade was redesignated the 1st London Brigade in the reorganisations following the Second Boer War.[3]

Territorial Force[edit]

This organisation was carried over into the Territorial Force (TF) created under the Haldane Reforms in 1908, the 1st London Brigade joining the 1st London Division. All of the Volunteer Battalions in the Central London area became part of the all-Territorial London Regiment and were numbered sequentially through the London brigades and divisions:[3][4][5][6]

1st London Brigade

- 1st (City of London) Battalion, London Regiment (former 1st VB, Royal Fusiliers)

- 2nd (City of London) Battalion, London Regiment (former 2nd VB, Royal Fusiliers)

- 3rd (City of London) Battalion, London Regiment (former 11th Middlesex RVC, 3rd VB, Royal Fusiliers)

- 4th (City of London) Battalion, London Regiment (former 1st Tower Hamlets RVC, 4th VB, Royal Fusiliers, from East London Brigade)

The 3rd Middlesex RVC and 2nd VB Middlesex Regiment became the 7th and 8th Battalions Middlesex Regiment respectively in the Home Counties Division, while the 17th Middlesex RVC became the 19th Battalion, London Regiment (St Pancras) in the 2nd London Division.

Brigade HQ was at Friar's House, New Broad Street (the HQ of 1st London Division). On the outbreak of war in August 1914 the brigade commander was Colonel The Earl of Lucan, a former Regular officer.[3]

First World War[edit]

The division was mobilised on the outbreak of the First World War in early August 1914 and, when asked to serve overseas (as, according to the Territorial and Reserve Forces Act 1907, Territorial soldiers were not obliged to serve overseas), most of the men of the division volunteered. Those who didn't, together with the many recruits, were formed into 2nd Line battalions, the 2/1st London Brigade, part of 2/1st London Division, which later became 58th (2/1st London) Division.[7] The battalions adopted the prefix '1/' (1/4th Londons, for example) to distinguish them from the 2nd Line battalions, which adopted the '2/' prefix (2/4th Londons).[8]

However, between November 1914 and April 1915, most of the battalions of the division were sent overseas[9] either to reinforce the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front or to overseas postings such as Malta (in the case of the 1/1st London Brigade) so as to relieve to Regular Army troops for service in France and Belgium and so, as a result, the 1st London Division was broken up.[10]

In early February 1916, however, the War Office authorised the 1st London Division to be reformed, now to be known as 56th (1/1st London) Division. Consequently, the brigade was reformed in France in February 1916, now as the 167th (1/1st London) Brigade, but with mostly different units, except the 1/1st and 1/3rd Londons (both original battalions of the brigade),[10] and both the 1/7th and 1/8th battalions of the Middlesex Regiment, both of which had previously been part of the Middlesex Brigade of the Home Counties Division and had served in Gibraltar before returning to England and fighting in France.[11]

The brigade served for the rest of the First World War in the trenches of the Western Front in Belgium and France, fighting a diversionary attack, alongside 46th (North Midland) Division, on the Gommecourt salient, to distract German attention away from the Somme offensive a few miles south in July 1916.[12] In March 1917, the 56th Division pursued the German Army during their retreat to the Hindenburg Line in March 1917, Arras, Langemarck, Passchendaele, Cambrai, First Arras, Albert and the Hundred Days Offensive.[10] The First World War finally came to an end with the signing of the Armistice of 11 November 1918. By the end of the war the 56th Division had suffered nearly 35,000 casualties.[13]

Order of battle[edit]

The brigade was composed as follows during the war:

- 1/1st (City of London) Battalion, London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers) (left May 1915, rejoined February 1916)[8]

- 1/2nd (City of London) Battalion, London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers) (left February 1915)

- 1/3rd (City of London) Battalion, London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers) (left May 1915, rejoined February 1916, left January 1918)

- 1/4th (City of London) Battalion, London Regiment (Royal Fusiliers) (left January 1915)

- 1/7th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment (from February 1916)[14]

- 1/8th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment (from February 1916)

- 167th Machine Gun Company, Machine Gun Corps (formed 22 March 1916, moved to 56th Battalion, Machine Gun Corps 1 March 1918)

- 167th Trench Mortar Battery (formed 14 June 1916)

- 4th Battalion, North Staffordshire Regiment (from 7 October until 15 November 1917)[15]

Due to a shortage of manpower in the BEF, British infantry brigades serving on the Western Front were reduced from four to three battalions throughout early 1918. Therefore, the 1/3rd Londons were, in early January, transferred to 173rd (3/1st London) Brigade of 58th (2/1st London) Division where they absorbed the 2/3rd Battalion and were renamed the 3rd Battalion once again. In February the 1/1st Londons absorbed the 2/1st Battalion and were renamed the 1st Battalion.[9]

Commanders[edit]

The following officers commanded 167th Brigade during the war:[16]

- Brigadier-General F. H. Nugent (5 February 1916)

- Lieutenant-Colonel E. J. King (acting, 22 July 1916)

- Brigadier-General G. H. B. Freeth (27 July 1916)

- Lieutenant-Colonel P. L. Ingpen (acting, 20 July 1917)

- Brigadier-General G. H. B. Freeth (23 July 1917)

- Lieutenant-Colonel R. H. Husey (acting, 26 April 1918)

- Brigadier-General G. H. B. Freeth (6 May 1918)

Between the wars[edit]

Disbanded after the war, the brigade, along with the rest of the division, was reformed in the Territorial Army (formed on a similar basis to the Territorial Force) as the 167th (1st London) Infantry Brigade, again with the same composition as it had before the First World War, of four battalions of the Royal Fusiliers.[17] The brigade had its headquarters in Birdcage Walk, London, at the Regimental Headquarters of the Scots Guards. In 1922 they dropped the 'battalion' from their title becoming, for example, 1st City of London Regiment (The Royal Fusiliers).[18]

Throughout the second half of the 1930s there was a need to increase the anti-aircraft defences of the United Kingdom, particularly so for London and Southern England. As a result, in 1935,[19] the 4th (City of London) Battalion, London Regiment (The Royal Fusiliers)[19] was converted into an artillery role, transferring to the Royal Artillery and converted into 60th (City of London) Anti-Aircraft Brigade, Royal Artillery and becoming part of 27th (Home Counties) Anti-Aircraft Group, 1st Anti-Aircraft Division (formed by conversion of the Headquarters of 47th (2nd London) Infantry Division).[20] They were replaced in the brigade by the 10th London Regiment (Hackney) from the 169th (3rd London) Infantry Brigade. The battalion was previously known as the 10th (County of London) Battalion, London Regiment (Hackney).[21] After the 47th Division was disbanded the 56th Division was redesignated as the London Division and the brigade became 1st London Infantry Brigade.

In 1938, after most of its battalions were posted away or converted to other units, the London Regiment ceased to exist and was disbanded. As a result, the 1st, 2nd and 3rd battalions became the 8th, 9th and 10th battalions, respectively, of the Royal Fusiliers[18] and the 10th London Regiment (Hackney) became the 5th (Hackney) Battalion, Royal Berkshire Regiment.[22] In the same year the 10th (3rd City of London) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) was transferred to the Royal Artillery, becoming 10th (3rd City of London) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (69th Searchlight Regiment)[23] but remained part of the Royal Fusiliers until 1940.[24] In 1938 when all British infantry brigades were reduced to three battalions, in August, the 5th (Hackney) Battalion, Royal Berkshire Regiment was transferred to 161st (Essex) Infantry Brigade of the 54th (East Anglian) Infantry Division and were replaced in the brigade by the London Irish Rifles (Royal Ulster Rifles)[25] from 3rd London Infantry Brigade,[26] previously the 18th London Regiment (London Irish Rifles) and, in 1908, the 18th (County of London) Battalion, London Regiment (London Irish Rifles).[27] Again in 1938 the division was converted and reorganised as a motorised infantry division.

Second World War[edit]

The Territorial Army, and therefore the brigade and the rest of the division, was mobilised between late August and early September 1939, and the German invasion of Poland began on 1 September, and the Second World War officially began two days later, after Britain and France declared war on Germany. Mobilised for full-time war service, the brigade was brought up to War Establishment strength in late October 1939 with large drafts of militiamen, men had been called up earlier in the year with the introduction of conscription in the United Kingdom and had just completed their basic training.

The division was destined not to be sent to France to join the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) but instead remained in the United Kingdom under Home Forces in a home defence role and was sent to Kent in April 1940 to come under command of XII Corps. Like most of the rest of the British Army after the events of Dunkirk, the division spent most of its time in an anti-invasion role training to repel an expected German invasion.[28]

In July 1940, after receiving the 35th Infantry Brigade from the recently disbanded 12th (Eastern) Infantry Division,[29] the division was reorganised as a standard infantry division[30] and later in the year, on 18 November, the division was redesignated and converted into the 56th (London) Infantry Division[30] and, on 28 November, the brigade was renumbered again as the 167th (London) Infantry Brigade.[26] In the same month the 1st Battalion, London Irish Rifles was transferred to 168th (London) Infantry Brigade[31] and was replaced by 15th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, a hostilities-only battalion raised only a few months before, making the brigade, temporarily, an all-Royal Fusiliers brigade. However, the 15th Fusiliers were posted elsewhere in February 1941 and replaced by 7th Battalion, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, a battalion created in September 1940, by the redesignation of 50th (Holding) Battalion.[32]

In November 1941 the brigade was sent to Suffolk and in July 1942 was preparing for a move overseas[33] and was inspected by General Sir Bernard Paget, at that time Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces, and also His Majesty King George VI.[34] The 56th Division, now composed largely of a mixture of Territorials, Regulars and wartime volunteers, left the United Kingdom on 25 August 1942, moving to Iraq and, together with 5th Infantry Division, became part of III Corps under the British Tenth Army, came over underall control of Persia and Iraq Command.[35] The brigade left for Egypt on 19 March 1943 and covered the journey by road, arriving there on 19 April 1943, and was then ordered to Tunisia, a distance covering about 3,200 miles.[36]

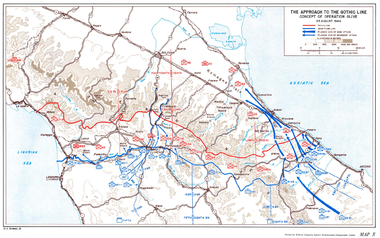

The division came under command of X Corps, part of the British Eighth Army, and saw only comparatively minimal service in the Tunisia Campaign, which ended in mid-May 1943 with the surrender of over 230,000 German and Italian soldiers, a number equal to Stalingrad the year before, who would later become prisoners of war. However, the 167th Brigade had been blooded, and all three battalions had suffered over 100 casualties each. Unable to see service in Operation Husky (the Allied invasion of Sicily), the brigade was destined to see almost two years service mountain warfare in the Italian Campaign and began training in amphibious warfare.

Now under command of Lieutenant General Mark Wayne Clark, the youngest three-star general in the U.S. Army,[37] and his U.S. Fifth Army, the 167th Brigade, with most of 56th Division (minus the 168th Brigade, temporarily replaced by 201st Guards Brigade), landed at Salerno on 9 September 1943, D-Day, where they were involved in tough fighting almost from the landing, with the 8th Royal Fusiliers in particular being battered by German Tiger tanks. Throughout the fighting the brigade, supported by A Squadron of the Royal Scots Greys, had suffered heavy casualties (roughly 360 per battalion)[38] and, after being relieved by other units, secured the Salerno beachhead and later advanced up the spine of Italy, crossing the Volturno Line and later fought at Monte Camino and crossed the Garigliano river in January 1944. With the rest of the Allied Armies in Italy (AAI), however, the brigade, by now very tired and below strength, was held up by the formidable German defences known as the Gustav Line (also the Winter Line).[39]

In January 1944, the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill envisioned an attempt to outflank the Winter Line, by way of an amphibious assault near Anzio, to capture Rome, the current objective which was being fought for in the Battle of Monte Cassino. As a result, after fighting at the Bernhardt Line and crossing the Garigliano, the division was pulled out of the line, and was transferred to Naples, to come under command of U.S. VI Corps. Arriving at Anzio on 12 February,[40] they were almost immediately involved in heavy combat in the Battle of Anzio in very tough and severe fighting to secure the beachhead, and sustained very heavy losses, which could not easily be replaced. In late March the division was relieved by the 5th British Division and moved to Egypt[41] to rest, refit, retrain and absorb replacements, after sustaining devastating casualties and enduring terrible conditions similar to those of the trenches of the Western Front during the First World War. By the time they were relieved, casualties in the brigade, and the rest of 56th Division, by now very weak, had been so severe that one unit, the 7th Battalion, Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry, were reduced to 60 all ranks, less than a company, from an initial strength of almost 1,000 officers and men.[42] Both Royal Fusiliers battalions had also suffered heavy casualties. In particular was the case of the 8th Battalion when, on 16 February during a heavy counterattack, X Company, was reduced to only one officer and 20 men. All that remained of Y Company was merely a single officer and 10 other ranks, after being heavily attacked by German infantry and Tiger tanks, which had fought against the battalion at Salerno. The battalion had, overall, suffered nearly 450 casualties at Anzio, more than half the strength of the battalion.[43] During the fighting on 18 February, the worst day of the counterattack, Second lieutenant Eric Fletcher Waters was killed and his son, Pink Floyd star Roger Waters, wrote a song in his memory–When the Tigers Broke Free–which describes the death of his father.

Whilst in Egypt the 167th Brigade, which had been reduced to less than 35% effective strength,[44] and division were both reinforced and brought up to strength largely by retrained anti-aircraft gunners of the Royal Artillery who had been transferred to the infantry, and had now found their original roles largely redundant, due largely to the absence of the Luftwaffe. While they were there the brigade was inspected, again, by General Sir Bernard Paget, now Commander-in-chief (C-in-C), Middle East Command, and who had inspected the division nearly two years earlier, shortly before the 56th ("The Black Cats") departed for overseas service.[45]

The 56th Division, now commanded by Major-General John Yeldham Whitfield, returned in July to Italy, where they were inspected by another man who had also inspected them two years prior, H.M. The King George VI. Almost as soon as it arrived the brigade, now under Eighth Army command, found itself fighting on the Gothic Line, throughout the summer, in Operation Olive (where Eighth Army suffered 14,000 casualties, at the rate of nearly 1,000 a day[46]) at the Battle of Gemmano, where the brigade and division suffered particularly heavy casualties. Due to these heavy losses suffered by the division (nearly 6,000)[47] in August and September and a severe lack of British infantry replacements in the Mediterranean theatre (although large numbers of anti-aircraft gunners were being retrained as infantry, they had only began their conversion in August and would not available until, at the earliest, October),[48] the 8th Royal Fusiliers and 7th Ox and Bucks were both reduced to cadres and transferred to the 168th (London) Brigade,[36] which was being disbanded, with the surplus personnel of the 8th Royal Fusiliers transferring to the 9th Battalion[36] and most of the men of 7th Ox and Bucks transferring to fill gaps in the 2/5th, 2/6th and 2/7th battalions of the Queen's Royal Regiment (West Surrey) of the 169th (Queen's) Brigade.[49] They were replaced in the brigade by 1st Battalion, London Scottish and 1st Battalion, London Irish Rifles, both from the 168th Brigade, although 1st London Irish had originally been with 167th Brigade at the outbreak of war. This, however, was not actually enough to keep them at full strength and the battalions were placed on a reduced establishment of only three rifle companies.[48] With the autumn rains and the oncoming winter, and no hope of a successful offensive in either weather, the Fifth and Eighth Armies reverted to the defensive and began preparing for an offensive on the Germans in the spring, scheduled for 1 April 1945.[50]

In April–May 1945 the brigade and division, with the rest of 15th Army Group, took part in the Spring 1945 offensive in Italy, where the 56th Division fought alongside 78th Battleaxe Division in the Battle of the Argenta Gap. The offensive effectively ended the Italian Campaign, and the brigade ended the war in Austria with the Eighth Army.[51]

Order of battle[edit]

167th Infantry Brigade was constituted as follows during the war:[40]

- 8th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (merged into 9th Bn 23 September 1944)

- 9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

- 1st Battalion, London Irish Rifles (Royal Ulster Rifles) (left 4 November 1940, rejoined 23 September 1944)

- 1st London Infantry Brigade Anti-Tank Company (formed 11 May 1940 until 27 November 1940, when renamed)

- 167th (London) Infantry Brigade Anti-Tank Company (renamed 28 November 1940, joined 56th Reconnaissance Battalion January 1941)[52] [53]

- 15th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (from 9 November 1940, left 13 February 1941)

- 7th Battalion, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry (from 14 February 1941, left 23 September 1944)

- 1st Battalion, London Scottish (Gordon Highlanders) (from 23 September 1944)

Commanders[edit]

The following officers commanded 167th Brigade during the war:[40]

- Brigadier C.R. Britten (until 11 July 1941)

- Brigadier J.C.A. Birch (from 11 July 1941 until 21 June 1943)

- Brigadier C.E.A. Firth (from 21 June 1943 until 29 January 1944)

- Brigadier J. Scott-Elliott (from 29 January until 27 October 1944, again from 7 November to 17 December 1944, and from 11 January 1945)

- Lieutenant Colonel J.R. Cleghorn (Acting, from 27 October until 7 November 1944)

- Lieutenant Colonel A.T. Law (Acting, from 17 December 1944 until 11 January 1945)

Post-war[edit]

The division was disbanded in Italy after the war in 1946. It was reformed in 1947 as the 56th (London) Armoured Division in the reorganisation of the Territorial Army.[51] However, the 167th Brigade was not reformed until 1956 when 56th Division was rereganised as an infantry division once more. As 167 (City of London) Infantry Brigade it had the following organisation:[54]

- Honourable Artillery Company (infantry battalion)

- 8 Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

- City of London Yeomanry (Rough Riders) (converted to infantry)

- 332 Signal Squadron, Royal Corps of Signals[55]

56th Division was disbanded in 1961.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Beckett, pp. 135, 185–6.

- ^ Dunlop, pp. 60–1.

- ^ a b c d Monthly Army Lists, 1889–1914.

- ^ Martin.

- ^ Money Barnes, Appendix IV.

- ^ Westlake.

- ^ "The 58th (2/1st London) Division of the British Army in 1914-1918". 1914-1918.net. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ a b Baker, Chris. "The London Regiment". The Long, Long Trail. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ a b "London Regiment - Regiment History, War & Military Records & Archives". forces-war-records.co.uk. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ a b c "The 56th (1st London) Division of the British Army in 1914-1918". 1914-1918.net. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "Middlesex Regiment - Regiment History, War & Military Records & Archives". forces-war-records.co.uk. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "Gommecourt, 1st July 1916 - The Combatants". gommecourt.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "56th (London) Division 1916-1918". 50megs.com. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Chris Baker. "The Middlesex Regiment". 1914-1918.net. Archived from the original on 28 June 2001. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "North Staffordshire Regiment - Regiment History, War & Military Records & Archives". forces-war-records.co.uk. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Becke (1936), p. 142.

- ^ "56 (1 London) Division (1930-36)" (PDF). British Military History. 14 December 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ a b "1st City of London Regiment (The Royal Fusiliers) [UK]". regiments.org. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ a b "4th City of London Regiment (The Royal Fusiliers) [UK]". regiments.org. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "1 Anti-Aircraft Division (1936-38)" (PDF). British Military History. 13 January 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ^ "10th London Regiment (Hackney) [UK]". regiments.org. Archived from the original on 22 February 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "The Royal Berkshire Regiment (Princess Charlotte of Wales's) [UK]". regiments.org. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "3rd City of London Regiment (The Royal Fusiliers) [UK]". regiments.org. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "The London Division (1937-38)" (PDF). British Military History. 14 December 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Administrator. "1920 - 1939". londonirishrifles.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ a b "1 London Division (1939)" (PDF). British Military History. 14 June 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ "London Irish Rifles [UK]". regiments.org. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "United Kingdom 1939-1940". British Military History. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "12 Infantry Division (1940)" (PDF). British Military History. 6 June 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ a b Joslen, p. 37.

- ^ "1940". London Irish Rifles Association. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Horan, Lt Col K. "Record of the 7th Battalion Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry June 1940-July 1942". LIGHTBOBS. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "BBC - WW2 People's War - 56 london division". BBC. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "January to June 1942". London Irish Rifles Association. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ "56th (London) Infantry Division" (PDF). British Military History.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Joslen, p. 228.

- ^ "U.S. Army's Youngest General – Mark W. Clark". Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ Blaxland, p. 34.

- ^ "56th Division". 50megs.com. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ a b c Joslen, p. 227.

- ^ Blaxland, p. 71.

- ^ "BBC - WW2 People's War - Oxs and Bucks at Anzio". BBC. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Paule, Edward D. "A History of the Royal Fusiliers Company Z". rogerwaters.org. Archived from the original on 31 August 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ D'Este, p. 515.

- ^ "7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JANUARY 1944-JUNE 1944". LIGHTBOBS. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Hoyt, p. 204.

- ^ Administrator. "September 1944". londonirishrifles.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ a b Blaxland, p. 202.

- ^ "7th Bn OXF & BUCKS LI JUNE 1944–JANUARY 1945". LIGHTBOBS. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Blaxland, p. 239.

- ^ a b "56 (LONDON) INFANTRY DIVISION (1943-45)" (PDF). British Military History. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2012.

- ^ Joslen, pp. 227–8.

- ^ 56th Recce Regiment at Recce Corps website.

- ^ Edwards, pp. 194–5.

- ^ Lord & Watson, p. 205.

References[edit]

- Becke, A. F. (1936). Order of Battle of Divisions Part 2A. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

- Ian F.W. Beckett, Riflemen Form: A Study of the Rifle Volunteer Movement 1859–1908, Aldershot: Ogilby Trusts, 1982, ISBN 0 85936 271 X.

- Blaxland, Gregory (1979). Alexander's Generals (the Italian Campaign 1944-1945). London: William Kimber. ISBN 0-7183-0386-5.

- John K. Dunlop, The Development of the British Army 1899–1914, London: Methuen, 1938.

- D.K. Edwards, A History of the 1st Middlesex Volunteer Engineers (101 (London) Engineer Regiment, TA) 1860–1967, London, 1967.

- d'Este, Carlo (1991). Fatal Decision: Anzio and the Battle for Rome. New York: Harper. ISBN 0-06-015890-5.

- Hoyt, Edwin Palmer (2002). Backwater War: the Allied Campaign in Italy, 1943–1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-97478-7.

- Cliff Lord & Graham Watson, Royal Corps of Signals: Unit Histories of the Corps (1920–2001)

- H.R. Martin, Historical Record of the London Regiment, 2nd Edn (nd)

- Joslen, H. F. (2003) [1960]. Orders of Battle: Second World War, 1939–1945. Uckfield, East Sussex: Naval and Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-474-1.

- R. Money Barnes, The Soldiers of London, London: Seeley Service, 1963.

- Ray Westlake, Tracing the Rifle Volunteers, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2010, ISBN 978-1-84884-211-3.