1940–1946 in French Indochina

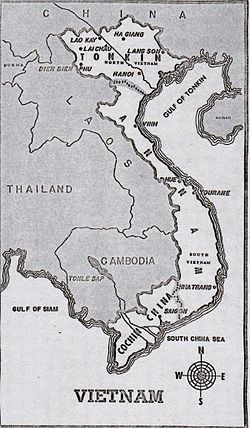

1940—1946 in French Indochina focuses on events that happened in French Indochina during and after World War II and which influenced the eventual decision for military intervention by the United States in the Vietnam War. French Indochina in the 1940s was divided into four protectorates (Cambodia, Laos, Tonkin, and Annam) and one colony (Cochinchina). The latter three territorial divisions made up Vietnam. In 1940, the French controlled 23 million Vietnamese, Laotians, Cambodians with 12,000 French soldiers, about 40,000 Vietnamese soldiers, and the Sûreté, a powerful police force. At that time, the U.S. had little interest in Vietnam or French Indochina as a whole. Fewer than 100 Americans, mostly missionaries, lived in Vietnam and U.S. government representation consisted of one consul resident in Saigon.[1]

The years 1940 to 1946 saw the rise of the communist-led Việt Minh insurgents whose objective was independence from France. The Việt Minh was most prominent in northern Vietnam (Tonkin) with a plethora of other, semi-allied insurgent groups developing in central (Annam) and southern (Cochinchina) Vietnam. During World War II (1939–1945), Japan stationed a large number of soldiers in Vietnam and reduced French influence. The Việt Minh also contested the growing Japanese influence. Late in WW II the United States gave limited assistance to the Việt Minh to assist it in its struggle against the Japanese. After World War II, France attempted to regain its colonial domination of Indochina (Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos) which led in 1946 to the outbreak of an insurgency against France by the Việt Minh. The U.S., which initially favored Vietnamese independence, came to support France due to Cold War politics and American fears that an independent Vietnam would be dominated by communists.

The most important events occurring in the 1940–1946 period were: (1) The creation of the Việt Minh by Ho Chi Minh and other communist leaders in 1941; (2) The Japanese takeover of the government of Vietnam from France in March 1945; (3) The partition of Indochina into two occupation zones to be pacified by the British in the south and China in the north as decided at the Potsdam Conference in July 1945; and (4) The August Revolution in August and September 1945 in which Ho Chi Minh declared independence from France; (5) The beginning of the First Indochina War, usually dated in December 1946, although preceded by many clashes, as France attempted to regain full control of Indochina.[2]

This timeline is continued in 1947–50 in the Vietnam War and subsequent articles. The article titled First Indochina War describes in more detail the struggle for independence from France led by the Việt Minh.

1940

[edit]- 22 September

The French government agreed to allow Japan to station soldiers in Tonkin after clashes between French and Japanese soldiers. During World War II Japan would station a large number of soldiers and sailors in Vietnam although the French administrative structure was allowed to continue to function.[3]

- 23 December

The rising power of Japan in Vietnam encouraged nationalist groups to revolt from French rule in Bac Son near the Chinese border and in Cochinchina. The American Consul in Saigon reported that "thousands of natives have been killed and more are in prison awaiting execution." He described "promiscuous machine-gunning" of Vietnamese civilians" by French soldiers.[4]

1941

[edit]- 10 May

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam, chaired by Ho Chi Minh (then known as Nguyen Ai Quoc), held its 8th Plenum in the Vietnamese village of Pac Bo in Cao Bằng province, near the border of Vietnam with China. This was the first time that Ho had set foot in Vietnam since 1911 after living in England, France, the United States, the USSR, and China.

The Central Committee created the Việt Minh as a broad-based, nationalist organization to struggle for independence from France and Japan. "By founding the Việt Minh, Ho Chi Minh brought together...the dynamism of nationalism and that of international communism.[5] As a temporary measure, the Central Committee emphasized patriotism and nationalism more than communist objectives. The resolution of the Central Committee toned down its previous support for seizing the land of landlords to redistribute it to peasants, instead promoting reductions of rent for land and land seizures only from French colonialists and Vietnamese "traitors."[6]

The Central Committee also concluded that the independence of Vietnam would be won only by armed rebellion which linked urban nationalism with rural rebellion. Armed forces were to be created in all areas of the country in which the Communist Party was active. Võ Nguyên Giáp would become the primary leader of the armed forces.[7]

- 14 July

Japan demanded and received approval from the Vichy French government to establish military bases in southern Vietnam in addition to bases in northern Vietnam.[8]

- 25 July

News that Japanese warships and troopships were near Cam Ranh Bay in Vietnam caused the U.S. to freeze Japanese assets, impose an embargo, and terminate the export of petroleum to Japan. For Japan the potential economic consequences of the U.S. actions were dire. The U.S. "now preferred to risk war rather than allow Japan to become more powerful."[9]

- 8 December

The United States declared war on Japan after the Japanese launched invasions throughout Southeast Asia and bombed Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Japan already had garrisoned 50,000 troops in Vietnam with the consent of the Vichy French government.[4]

1943

[edit]- April

U.S. Navy Commodore Milton E. Miles, stationed in Chongqing, China proposed that twenty Office of Strategic Services (OSS) agents be parachuted into the Central Highlands of Vietnam to organize guerrilla bands among the highland peoples to oppose the Japanese forces. The plan was approved, but never implemented. The United States, however, established a network of Vietnamese and French colonials for intelligence and espionage.[10]

1944

[edit]- 24 January

President Roosevelt of the United States wrote that "Indo-China should not go back to France...France has had the country...one hundred years, and the people are worse off than they were at the beginning." Roosevelt envisioned a post-World War II trusteeship for Indochina.[11]

- 8 July

The French Sûreté discovered a Việt Minh base in Cao Bằng Province with arms and other material and warned of an immediate need "to re-establish authority." The Việt Minh at this time controlled much of the border areas on northern Vietnam in Cao Bằng, Bắc Kạn, and Lạng Sơn provinces.

November

A major peasant revolt erupted north of Hanoi in Thai Nguyen and Tuyen Quang provinces. It stemmed out of frustration at agricultural policies that exacerbated an ongoing famine, with the French imposing unfavourable exchange ratios, charging laborers fees to work, and expropriating the crops for Japan - who already appropriated rice-growing land for industrial crops like jute. 6,000-7,000 peasants, aided by Viet Minh involvement, fought Foreign Legionnaires until artillery and tanks dispersed them into the jungles. [12]

25 December

Viet Minh forces won their first battle against the French, overrunning remote French outposts and capturing weaponry.

- 27 December

U.S. General Albert C. Wedemeyer in Chongqing reported that Ambassador Patrick J. Hurley was displeased with aid given to intelligence operatives in Vietnam. Hurley "had increasing evidence that the British, French, and Dutch are working...for the attainment of imperialistic policies and he felt we should do nothing to assist them in their endeavors which run counter to U.S. policy." Hurley was reflecting President Roosevelt's position.[13]

- 31 December

The Việt Minh claimed to have 500,000 members of whom 200,000 were in Tonkin, 150,000 in Annam, and 100,000 in Cochinchina. The Việt Minh military and political structure was strongest and best organized in Tonkin."[14]

1945

[edit]

- 23 January

United States Airforce planes shot down three British bombers over Indochina, mistaking them for Japanese planes. The British were conducting clandestine operations in Indochina without informing the United States.[15]

- February

A famine began in northern Vietnam which would result in about one million people dying—approximately 10 percent of the population of Tonkin and Annam—within a few months. Vietnamese blamed France and Japan for the disaster. The Việt Minh were credited with seizing stocks of rice and distributing it to the poor to ameliorate the famine.[16]

- 20 February

President Roosevelt at the Yalta Conference said he was "in favor of anything that is against the Japanese in Indochina provided that we do not align ourselves with the French."[17]

- 7 March

U.S. General Claire Lee Chennault in Chongqing said that "any help or aid given by us [to Vietnam] shall be in such a way that it cannot possibly be construed as furthering the political aims of the French."[17]

- 9 March

Japan demanded that the French colonial government of Vietnam be placed under its control, including the banks and French and Vietnamese armed forces. When the French did not immediately accede to their demands the Japanese seized the government by force, defeating the French in several battles. The reason for the Japanese action was a fear that the United States would invade Vietnam. Japan was fortifying its defenses and eliminating the remaining French influence in the country. Japan persuaded the former emperor Bảo Đại to declare Vietnam independent of France and set up a puppet government headed by Trần Trọng Kim.[18]

- 10 March

U.S. General Robert B. McClure in China authorized air support to the French resisting Japanese control of Indochina. However, President Roosevelt in Washington said that he wanted "to discontinue colonialization" in Southeast Asia and did not wish that any military assistance be given to the French in Indochina.[19]

- 14 March

French Leader Charles de Gaulle in Paris criticized the United States and its allies for not helping the French in Indochina. De Gaulle affirmed that France would regain control of Indochina.[20]

- 17 March

Ho Chi Minh and Phạm Văn Đồng met with American Captain Charles Fenn who worked for the Office of Strategic Services in Kunming, China. Three days later the OSS agreed to provide radio equipment, arms, and ammunition to the Việt Minh. Ho agreed to gather intelligence, rescue downed American pilots, and sabotage Japanese installations. Fenn was favorably impressed with Ho.[21]

- 18 March

Yielding to pressure from the French and his advisers, President Roosevelt authorized American aid to the French in Indochina. The French would charge that U.S. aid was limited and late.[22] Historians disagree about whether or not Roosevelt's action was a change in his policy of opposing a French return to power in Indochina.[23]

- 24 March

France issued a declaration, which assumed that France would regain control of Vietnam, announcing the formation of an Indochinese Federation in which France would extend additional rights to Indochinese, but retain control of defense and foreign affairs. Vietnamese nationalists of all political persuasions condemned the declaration, especially the continued division of Vietnam into three parts: Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina.[24]

- 29 March

Ho Chi Minh met with U.S. General Chennault in Kunming, China. Chennault thanked Ho for rescuing downed American pilots. Ho requested and received an autographed photograph of Chennault which he used to demonstrate the support he had from the United States.[25]

- 7 April

The United States Department of War authorized General Wedemeyer in China to support French forces in Vietnam "providing they represent only a negligible diversion" from U.S. priorities. Wedemeyer was hard pressed for resources and dropped mostly medicine to the French.[26]

- 12 April

U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt died. Harry S. Truman became president.

- 13 April

U.S. Under Secretary of the Army Robert A. Lovett said that former President Roosevelt's prohibition on a definite U.S. policy regarding Indochina was a "serious embarrassment to the military." Lovett's statement initiated a debate among Washington government agencies.[27]

- 16 April

A policy paper given new U.S. President Truman by the European office of the Department of State advocated a pro-French policy in Indochina. Southeast Asian specialists at the State Department complained later that the policy paper deliberately excluded information about President Roosevelt's opposition to the French in Indochina.[28]

- 30 April

The United States Department of State approved a policy paper stating that the U.S. would not oppose restoration of French sovereignty in Indochina, but would seek to ensure that the French permitted the Indochinese peoples more autonomy. This new policy was a large step away from Roosevelt's previous opposition to the French, but, except for Asian experts in the State Department, there was little support in the U.S. government for continuing to follow Roosevelt's policy.[27]

- 28 May

U.S. General Wedemeyer in China complained of a "British and French plan to reestablish their pre-war political and economic positions in Southeast Asia" and said they were using American supplies to "invade Indochina...and re-establish French imperialism. In the response from Washington, Wedemeyer was informed that the U.S. now "welcomes French participation in the Pacific War."[29]

- 2 June

The U.S. Secretary of State sent a report to President Truman stating that "the United States recognizes French sovereignty over Indochina." Thus, the U.S. had reversed Roosevelt's opposition to supporting the French in their efforts to regain control of Indochina.[30]

During this month, the Japanese also launched a series of raids against the Viet Minh, with the 21st Division striking bases in Tonkin while the military police arrested 300 suspects. [31]

- 16 July

Three U.S. soldiers from the OSS led by Major Allison Thomas parachuted into the Việt Minh's base camp in northern Viet Nam. They were cordially greeted. Thomas said "Việt Minh league is not Communist. Stands for freedom and reforms against French harshness."[32] The objective of the Americans was to organize a guerrilla group to attack a Japanese railroad. Ho Chi Minh introduced himself to them as Mr. Hoo.[33]

19 July

A major Viet Minh strike occurred at Tam Dao internment camp, in which 500 soldiers killed fifty Japanese guards and officials, freeing French civilians who were escorted to the Chinese border. [34]

- 26 July

The Potsdam Conference of victorious allies decided that the British would accept the surrender of Japanese troops in Indochina south of the 16th parallel and China would accept their surrender north of the 16th parallel.

- 17 August

The August Revolution broke out. The National Congress of the Việt Minh declared a general uprising to take political power in Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh was elected to preside over the National Liberation Committee. The call for the general uprising was prompted by the news that Japan would surrender.[35]

- 19 August

The Việt Minh organized a very large demonstration in Hanoi and took charge of the government in the city and much of northern Vietnam.[36]

- 22 August

American intelligence officer Major Archimedes L. Patti arrived in Hanoi to secure the release of American POWs held by the Japanese in Indochina. Accompanying Patti was a French team headed by Jean Sainteny, ostensibly in Indochina to care for French POWs. Ho Chi Minh warned Patti that Sainteny's real objective was to reassert French control over Vietnam.[37] Patti reported to his superiors in China that "Việt Minh strong and belligerent and definitely anti-French. Suggest no more French be permitted to enter French Indo-China and especially not armed." Patti refused to allow the release of 4,500 French soldiers imprisoned in Hanoi by the Japanese.[38]

- 26 August

Ho Chi Minh entered the city of Hanoi. The Việt Minh military force that had taken control of Hanoi consisted of about 200 men. The Việt Minh army numbered about 1,200 trained men and hundreds of thousands of militia, men and women, most of them without firearms.[39]

- 2 September

Japan signed the instrument of surrender in Tokyo Bay ending World War II.

In Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh declared independence from France, the creation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, and the formation of his government. In his speech Ho referred to the U.S. Declaration of Independence and appealed to the victorious allies of World War II "to oppose the wicked schemes of the French imperialists, and...to recognize our freedom and independence."[40]

In Saigon and southern Vietnam, there was political disorder with competition, often violent, among religious sects and political factions. The Việt Minh organized a large demonstration which resulted in attacks on French residents of the city. A recently arrived team of American OSS personnel enlisted Japanese soldiers to protect French citizens.[41]

- 9 September

The main force of a 150,000 men Chinese army arrived in Hanoi to accept the surrender of Japanese forces and preserve law and order north of the 16th parallel of Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh initially cooperated with the Chinese who unceremoniously evicted the French from the Governor-General's Palace.[42] American advisers accompanied the Chinese but were ordered "not to become involved...in French-Chinese relations or in any way become associated with either side in possible conflicts."[43]

- 10 September

To combat disorder and establish Vietnamese rule in southern Vietnam, nationalists set up a Committee of the South in Saigon. The committee was composed of 13 persons, including 4 members of the communist party, and headed by a nationalist.[44]

- 13 September

British forces of the Indian Army numbering 20,000, led by General Douglas Gracey, entered Saigon to accept the surrender of Japanese troops south of the 16th parallel of Vietnam.[45] Gracey refused to meet with Vietnamese leaders and said that "Civil and military control [of Vietnam] by the French is only a matter of weeks."[46]

- 20 September

General Philip E. Gallagher, commander of the U.S. military mission in Hanoi, reported that Ho Chi Minh was a "product of Moscow" but that "his party represented the real aspirations of the Vietnamese people for independence.[47]

- 21 September

General Gracey, commander of British forces in Saigon, declared martial law and released and armed more than 1,000 French soldiers held prisoner by the Japanese.

- 23 September

The French Flag once again flew over the major government buildings of Saigon. Historian Frederick Logevall has suggested this as the start date for the Việt Minh war against the French.[48]

- 24 September

In Saigon, the Việt Minh declared a general strike and they and other nationalist groups attacked French, British, and Japanese, and European civilians. About 20,000 French citizens lived in Saigon. Over the next several days, 150–300 French and Eurasian civilians and about 200 Vietnamese were killed.[49]

- 26 September

Lt. Colonel A. Peter Dewey, a relative of U.S. presidential nominee Thomas E. Dewey, was killed, apparently by mistake, by Việt Minh soldiers in Saigon – the first American to die in Vietnam. Dewey was in Saigon to arrange for the repatriation of American prisoners of war captured by the Japanese.[50] Dewey had complained about abuses of power by British and French soldiers in Saigon and had been prohibited by British commander Douglas Gracey from flying a U.S. flag on his vehicle. The Việt Minh apparently thought that he was French.[51]

Dewey's appraisal of the situation was that "Cochinchina is burning, the French and the British are finished here, and we [the United States] ought to clear out of Southeast Asia."[52]

French general Marcel Alessandri, visiting Hanoi, asked help of U.S. General Gallagher in persuading the Chinese military forces to release all French prisoners, rearm the French police and military, and return control of the radio station and public utilities to the French. The Chinese commander agreed only to release French prisoners.[53]

- 27 September

In a meeting with U.S. Army officers General Gallagher and Major Patti, Ho Chi Minh "expressed the fear that the Allies considered Indochina a conquered country and that the Chinese came as conquerors." Gallager and Patti attempted to reassure him and urged continued negotiations with the French.[53]

- 4 October

U.S. General Gallagher in Hanoi reported a "noticeable change in the attitude of the Annamites [Vietnamese] here...since that became aware of the fact that we were not going to interfere and would probably help the French.[53]

- 5 October

French general Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque arrived in Saigon as head of a regiment of French soldiers. He and General Gracey and a large number of Japanese troops pushed the Việt Minh out of Saigon and captured nearby areas. More than 1,000 Japanese soldiers deserted rather than fight with the British and French and fought on the side of the Việt Minh. By early November, the British and Japanese fighting the Việt Minh had suffered 19 and 54 soldiers killed respectively.[54]

- 9 October

The British and French governments concluded an agreement in London in which the British recognized France as the "sole legitimate authority" south of the 16th parallel. The United Kingdom agreed to help transport French troops to southern Vietnam to reinforce General Leclerc. In the meantime, the agreement specified "close and friendly cooperation between the French and British commanders."[55] The ships used to transport French soldiers included eight U.S. flag vessels, the first significant American aid to the French in Vietnam.[56]

- 25 October

French General Leclerc with 35,000 French, British, and Japanese soldiers launched an offensive against the nationalist forces, including the Việt Minh, who controlled much of the countryside of southern Vietnam. By the middle of December, Leclerc had gained control of most towns and cities south of the 16th parallel. The Việt Minh and others began a guerrilla campaign against the French. A journalist said, "What was needed was not 35,000 men...but 100,000 and Cochinchina was not the only problem."[57]

- 31 October

Former Catholic monk and supporter of French leader Charles de Gaulle, Thierry d'Argenlieu arrived in Saigon as High Commissioner for Indochina. Described by one wag as having "the most brilliant mind of the twelfth century", D'Argenliu shared De Gaulle's belief that the French empire, including Indochina, should be retained intact.[58]

- 11 November

At a meeting in Hanoi the Indochina Communist Party dissolved itself, citing a need to foster national unity in search of independence from France as the reason. Communist domination of the Việt Minh had been criticized by other nationalist groups and Ho Chi Minh had apparently decided that unity was more important for the moment than communist ideology.[59]

- 1 December

Ho Chi Minh began negotiations in Hanoi with French Commissioner for Tonkin, Jean Sainteny. Ho's concern was that the 150,000 Chinese troops in northern Vietnam would not go home and that they were aiding the Việt Minh's rival nationalist groups, the Vietnamese Nationalist Party and the Nationalist Party of Greater Vietnam. Ho had decided to seek cooperation with the French even though that might delay Vietnam attaining independence from France.[60]

- 12 December

U.S. General Gallagher departed Hanoi and shut down the U.S. advisory mission in northern Vietnam. The U.S. was blamed by the French for colluding with the Việt Minh and by the Việt Minh for facilitating the resumption of French control over Indochina[61]

- 31 December

The French estimated that the Việt Minh army in northern Vietnam, mostly Tonkin, numbered 28,000 men.[62]

1946

[edit]- 1 January

After negotiations with other nationalist groups, a new government in Hanoi was set up with Ho Chi Minh as president and Nguyen Hai Than as vice president. Elections were to follow to elect a national assembly with some seats guaranteed to two nationalist organizations. Earlier, Ho had abolished the communist party of Vietnam to emphasize his nationalist credentials.[63]

- 6 January

In an election for the National Assembly in northern Vietnam, the Việt Minh and allied nationalist groups won 300 of 350 seats. Most observers believed the elections were fair, although there were a few charges that voters had been intimidated.[64]

- 5 February

French General Leclerc declared that, as a result of his military campaigns against nationalist groups, "the pacification of Cochinchina [southern Vietnam] is entirely achieved."[65] Author Bernard Fall later commented that Leclerc gained control of Cochinchina but only "to the extent of 100 yards on either side of all major roads."[66]

- 20 February

Despite his apparent success pacifying Cochinchina General Leclerc appealed to France to grant concessions to the Việt Minh. At this time Ho Chi Minh was engaged in negotiations with French representative Sainteny in Hanoi. De Gaulle and d'Argenlieu opposed any concessions toward independence for Vietnam.[67]

- 27 February

Twenty-one thousand French soldiers boarded ships in Saigon for Tonkin with the goal of reoccupying northern Vietnam, putting pressure on Ho Chi Minh to come to terms in his negotiations with France about the future of Vietnam, and gaining the release of 3,000 French soldiers still held prisoner in Hanoi.[68]

- 28 February

France completed an agreement with the Chinese government for the withdrawal of Chinese soldiers from Vietnam north of the 16th parallel.[69]

Việt Minh leader Ho Chi Minh sent a telegram to U.S. President Truman appealing to the U.S. "to interfere urgently in support of our [Vietnamase] independence." This was one of several letters and telegrams that Ho sent to the United States appealing for support. The U.S. never answered him.[70]

- 4 March

The British completed their withdrawal from Vietnam south of the 16th parallel, leaving French forces in control of the government of Cochinchina.[69]

- 6 March

In the morning, the French armada of 35 ships and 21,000 men attempted to land at Haiphong in Tonkin. Their landing was prevented by Chinese soldiers occupying the harbor who exchanged fire with the French ships. The Chinese pressured both the French and the Vietnamese to sign an agreement.

In the afternoon, Ho Chi Minh and Sainteny concluded a provisional agreement. France recognized the "Republic of Vietnam" as a "free state" within the French Union. The Vietnamese agreed to the stationing of 25,000 French troops for five years in Tonkin to replace the departing Chinese. France agreed to allow an election to decide whether the three regions of Vietnam would be united.

Ho Chi Minh was severely criticized by other nationalists for the agreement, which offered Vietnam less than independence and that only on a provisional basis. He reportedly said that "I prefer to sniff French shit for five years than eat Chinese shit for the rest of my life."[71]

- 10 April

Insurgent leader Nguyễn Bình in Cochinchina announced the creation of a National United Front to unite nationalist groups to fight the French and gain independence. In June, Nguyen would join the Communist party but would retain some independence from the Việt Minh in northern Vietnam.[72]

- 31 May

Ho Chi Minh left Vietnam for negotiations concerning Vietnamese independence in Paris. He was warmly received in France.[73]

- 1 June

French High Commissioner for Indochina Thierry d'Argenlieu in Saigon said that the 6 March agreement between the Việt Minh and the French did not apply to Cochinchina and announced the formation of the Republic of Cochin China for southern Vietnam.[74]

- 8 June

General Leclerc (who had departed Vietnam) wrote a letter to the French ruling party stating that the war in Vietnam was practically won and that France should not concede much to the Vietnamese negotiators in Paris. Leclerc said "it would be very dangerous for the French representatives at the negotiations to let themselves be fooled by the deceptive language (democracy, resistance, the new France) that Ho Chi Minh and his team utilize to perfection."[75]

- 15 June

The last Chinese soldiers departed northern Vietnam.

- 21 June

Illustrating the paucity of military capability among the Việt Minh and other nationalist groups resisting the French, a commander named Nguyen Son in the Central Highlands had about 12,000 fighters under his command, but one of his brigades had only 1,500 rifles for 4,000 men. Nevertheless, Nguyen was able to turn back a French offensive aiming to capture the coastal city of Qui Nhơn.[76]

- 9 August

The U.S. vice-consul in Hanoi, James L. O'Sullivan, reported "an imminent danger of an open break between the French and Viet Nam", and said "that, although the French could quickly overrun the country, they could not...pacify it except through a long and bitter military operation."[74]

- 31 August

A report by the French authorities in southern Vietnam (Cochinchina) was much more pessimistic than earlier reports. Insurgent groups, earlier reported as destroyed, had reconstituted themselves and the Việt Minh was gaining strength by accepting "semi-complicity" by the population, e.g. cooperating openly with the French and secretly with the Việt Minh.[77]

- 14 September

In Paris, Ho Chi Minh achieved a modus vivendi in negotiations with France by which a ceasefire in southern Vietnam was to come into effect on 30 October. France, however, did not promise independence for Vietnam. The fact that the ceasefire proved to be effective was a measure of the control the Việt Minh had over nationalist groups in southern Vietnam even though its power base was in the north.[78]

- 20 October

Ho Chi Minh arrived in Haiphong after an absence of more than 4 months. He had been negotiating, with little success, for Vietnamese independence with the French government in Paris.[79] In his absence, Việt Minh military leader Võ Nguyên Giáp had prepared for war with the French. With the departure of the Chinese army in June, Giap had crushed the pro-Chinese nationalist groups in northern Vietnam, killing hundreds or thousands of their followers and, despite a cease fire, engaged the French when they attempted to expand their control out of the cities to the countryside. The Việt Minh, said historian Frederik Logevall, "previously had genuine legitimacy in calling themselves a broad-based nationalist front" but were now "synonymous with the Communist movement."[80]

- 31 October

The French estimated that Việt Minh fighters in northern Vietnam (mostly Tonkin) numbered 40,000 to 45,000, an increase from an estimated 28,000 at the end of 1945. In southern Vietnam, there were probably only about 5,000 Việt Minh fighters of unquestioned loyalty, although many other nationalistic insurgent groups existed. The French had 75,000 soldiers in Vietnam, more than one-half in the north.[62]

- 8 November

The Việt Minh in Hanoi demanded that the three regions of Vietnam—Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina—be united into one.[81]

- 10 November

The anti-communist leader of the French-backed government of Cochinchina, Dr. Nguyen Van Thinh, committed suicide.[82]

- 20 November

Fighting broke out in Haiphong between the French and the Việt Minh. A cease fire was arranged.[81]

- 22 November

The French commander in Tonkin was ordered "to teach a hard lesson to those [the Việt Minh] who have so treacherously attacked us. By every possible means you must take complete control of Haiphong and force the Vietnamese government and army into submission."[83]

- 23 November

In what became known as the Haiphong Massacre, after giving the Việt Minh an ultimatum to withdraw from Haiphong, the French under General Jean Étienne Valluy began a naval and aerial bombardment of the city that endured 2 days and destroyed much of the Vietnamese and Chinese quarters of the city. An estimated 6,000 civilians were killed. French Commissioner General d'Argenlieu in Paris informed Valluy that he approved of the bombardment.[84]

- 5 December

As American diplomat Abbot Low Moffat prepared to meet with Ho Chi Minh in Hanoi, Under Secretary of State Dean Acheson instructed him to "keep in mind Ho's clear record as [an] agent of international communism." Acheson said that the worst outcome of the French/Việt Minh struggle in Vietnam would be a "Communist-dominated, Moscow-oriented state." The policy struggle in the Department of State about Vietnam between the Europeanists, represented by Acheson, and the Asian hands had been won by the Europeanists whose priority was maintaining a friendly French government in power in France to further American aims in Europe.[85]

- 9 December

American diplomat Moffat reported to the Department of State about his visit to Hanoi. Moffat had met with Ho Chi Minh. His brief was to assure Ho of U.S. support of "autonomy" for Vietnam but to warn Ho not to use force to achieve his objective. Ho asked for U.S. assistance and offered a naval base to the U.S. at Cam Ranh Bay. Moffat reported to Washington that the Việt Minh communists were in control of the Vietnamese government and that a French presence in Vietnam was required to prevent an expansion of Soviet and possible Chinese communist influence. However, Moffat also expressed sympathy with the nationalist aspirations of the Việt Minh and said that France had no viable option other than compromise.[86]

- 17 December

The U.S. Department of State in Washington informed its personnel worldwide that the Việt Minh were communists and that the French presence in Vietnam was imperative "as an antidote to Soviet influence [and] future Chinese imperialism. Thus, Vietnam was identified by the United States as a participant in the intensifying Cold War tension between the Soviet Union and the United States. In the opinion of some authorities, this was a moment in which the U.S. might have averted the First Indochina War (and the later Vietnam War) had the U.S. told France bluntly to observe the 6 March agreement which recognized the Việt Minh as a legitimate government authority.[87]

Socialist Léon Blum became premier of France. A few days earlier, Blum had stated that "We must reach agreement [with the Việt Minh] on the basis of independence [for Vietnam]". Blum's assumption of power came too late to decelerate the movement toward outright war between the French and the Việt Minh. France feared that any concessions to the Việt Minh would inspire rebellion in France's African colonies plus the takeover by the Việt Minh of all French assets in Indochina.[88]

French and Việt Minh forces clashed in Hanoi with casualties on both sides as the French advanced to take control of the city.[89]

French leader Charles de Gaulle met with French High Commissioner for Indochina Thierry d'Argenlieu in France and expressed support for the Commissioner's uncompromising stance against independence for Vietnam.[90]

- 19 December

The Việt Minh launched their first ever large-scale attack against the French. The Việt Minh military leader, Võ Nguyên Giáp, had three divisions of soldiers stationed near Hanoi and used his few pieces of artillery to blast away at the French. French negotiator Jean Sainteny was seriously wounded when a land mine blew up his car. It would take the French two months to expel the Việt Minh from Hanoi as combat spread to all parts of Vietnam.

This date and the Việt Minh attack—actually a counter-attack—is often considered by pro-French historians the beginning of the First Indochina War.[91]

- 21 December

Ho Chi Minh broadcast by radio a nationwide appeal to Vietnamese to rise up in resistance to French rule.[92]

- 23 December

The Communist Party of France voted in favor of a message supporting French troops in Vietnam. The communists were attempting to maintain a place in the Cabinet of Ministers and in mainstream politics of France and had little interest in supporting the Việt Minh in Vietnam.[93]

- 24 December

U.S. State Department Asian expert John Carter Vincent wrote that the French lacked the military strength to gain control of Vietnam, lacked public support in France for the war, and had a weak and divided government. He predicted that guerrilla war would continue indefinitely.[92]

- 31 December

The Việt Minh army numbered about 60,000 of whom 40,000 had rifles. Another 40,000 were in militia and para-military organizations.[94]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Logevall, Fredrik (2012), Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America's Vietnam, New York: Random House, p.32, 72

- ^ Tonnesson, Stein (1985), "The Longest Wars: Indochina 1945–1975", Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 22, No. 1, p. 10. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- ^ Bowman, John S. (1985), The World Almanac of the Vietnam War, New York: Pharos Books, p. 14

- ^ a b Spector, Ronald H. (1983), Advice and Support: The Early Years, 1941–1960, Washington, D.C.: Superintendent of Documents, p. 18

- ^ Logevall, pp. 34–36

- ^ Duiker, William J. (1996), The Communist Road to Power in Vietnam, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, p. 721-73

- ^ Duiker, pp. 73–75

- ^ Logevall, p. 39

- ^ Logevall, pp 41–42

- ^ Spector, pp. 26–27

- ^ Spector, p. 22, Tonnesson (1985), p. 11

- ^ Hanyok, Robert (1995). "Guerillas in the Mist: COMINT and the Formation and Evolution of the Viet Minh 1941-45" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Spector, p. 28

- ^ Pentagon Papers, "Vietnam and the U.S., 1940–1950", p. B-4

- ^ Spector, p. 47

- ^ Logevall, p. 81

- ^ a b Spector, p. 30

- ^ Logevall, pp. 67–72

- ^ Spector, pp. 31–32

- ^ Logevall p 73

- ^ Logevall, pp 82–84

- ^ Spector, pp. 33–34

- ^ See "Tonnesson, Stein, "Franklin Roosevelt, Trusteeship, and Indochina: A Reassessment" in The First Vietnam War (2007, Eds. Mark Atwood Lawrence and Fredrik Logevall, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 56–73

- ^ Logevall, pp. 75–76

- ^ Logevall, p. 84

- ^ Spector, p. 34

- ^ a b Spector, p. 44

- ^ Tonnessson (2007), p.68-69

- ^ Spector, p. 49

- ^ Spector, p. 45

- ^ Hanyok, Robert (1995). "Guerillas in the Mist: COMINT and the Formation and Evolution of the Viet Minh 1941-45" (p.107).

- ^ Logevall, p. 85

- ^ "Ho Chi Minh and the OSS", History Net, http://www.historynet.com/ho-chi-minh-and-the-oss.htm, accessed 29 Oct 2015

- ^ Hanyok, Robert (1995). "Guerillas in the Mist: COMINT and the Formation and Evolution of the Viet Minh 1941-45" (p.107).

- ^ Duiker, p. 92, 96

- ^ Duiker, p. 98

- ^ Logevall, p. 100

- ^ Spector, p. 57-59

- ^ Logevall, p. 93; Marr, David G. (2007), "Creating Defense Capacity in Vietnam, 1945–1947", in The First Vietnam War, Mark Atwood Lawrence and Frederik Logevall, eds., Cambridge: Harvard University Press, p. 76

- ^ Logevall, pp. 97–98

- ^ Spector, p. 66

- ^ Logevall, pp. 109–110

- ^ Springhall, John (Jan 2005), "'Kicking out the Vietnminh': How Britain Allowed France to Reoccupy South Indochina, 1945–46, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 40, No. 2, p. 119. Downloaded from JSTOR.; " Spector, p. 56

- ^ Pentagon Papers, "Vietnam and the U.S., 1940–50", p. B-37

- ^ "The Vietnam War: Seeds of Conflict", The History Place, http://www.historyplace.com/unitedstates/vietnam/index-1945.html, accessed 1 Nov 2015

- ^ Logevall, p. 113

- ^ Spector, p. 61

- ^ Logevall, p. 115

- ^ Pentagon Papers, p. B-38; Logevall, p 115; Springhall, p. 123

- ^ Morgan, Ted (2010). Valley of Death: The Tragedy at Dien Bien Phu that Led America into the Vietnam War. New York: Random House. p. 66.

- ^ Lee, Clark (1947). "French Colonials Are Sad Sacks". One Last Look Around. Duell, Sloane and Pearce. pp. 200–211.

- ^ Logevall, p. 117

- ^ a b c Spector, p. 64

- ^ Logevall, pp. 117–118

- ^ Pentagon Papers, p. B-39

- ^ Logevall, pp. 118–119

- ^ Pentagon Papers pp. B-39-40; Logevall, p. 119

- ^ Logevall, pp. 124–125

- ^ Pentagon Papers, pp B-42-43

- ^ Logevall, p. 128

- ^ Spector, pp 72

- ^ a b Marr, p. 101

- ^ Duiker, pp. 116–117

- ^ Duiker, p. 122

- ^ Marr, p. 77

- ^ Logevall, p. 131

- ^ Logevall, pp. 131–132

- ^ Logevall, pp. 132–133

- ^ a b Pentagon Papers, B-47

- ^ National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/todays-doc/?dod-date=228;, Logevall, p. 104

- ^ Logevall, p. 133

- ^ Logevall, p. 153

- ^ Logevall, pp 137–139

- ^ a b Spector, p. 79

- ^ Logevall, pp. 149–150

- ^ Marr, p. 94

- ^ Marr, p. 96

- ^ Tonnesson (1985), p. 13

- ^ Tonnesson, Stein (2009), Vietnam 1946: How the War Began, Berkeley: University of California Press, p 89

- ^ Logevall, p. 151

- ^ a b Spector, p. 81

- ^ Logevall, p. 154

- ^ Logevall, p. 157

- ^ Logevall, pp. 157–158; Spector, p. 81; Tonnesson (1985), p. 13

- ^ Spector, p. 83-84

- ^ Logevall, pp 158–159

- ^ Logevall, pp 158–160

- ^ Logevall, p. 160; Tonnesson (1985), p. 16

- ^ Logevall, p. 162

- ^ Logevall, p. 165

- ^ Logevall, p. 161-164

- ^ a b Spector, p. 83

- ^ Tonnesson (1985), p. 17

- ^ Asprey, Robert B. (1994), War in the Shadows: The Guerrilla in History, New York: William Morrow and Company, p. 480