Acrodermatitis enteropathica

| Acrodermatitis enteropathica | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Acrodermatitis enteropathica, zinc deficiency type[1] |

| |

| Acrodermatitis enteropathica inheritance | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Dry skin, Emotional lability, Blistering of skin[2] |

| Causes | Mutation of the SLC39A4 gene[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Skin biopsy, Plasma zinc level[3] |

| Treatment | Dietary zinc supplementation[1] |

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal recessive metabolic disorder affecting the uptake of zinc through the inner lining of the bowel, the mucous membrane. It is characterized by inflammation of the skin (dermatitis) around bodily openings (periorificial) and the tips of fingers and toes (acral), hair loss (alopecia), and diarrhea. It can also be related to deficiency of zinc due to other, i.e. congenital causes.[3][4]

Other names for acrodermatitis enteropathica include Brandt syndrome and Danbolt–Cross syndrome.[5]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Individuals with acrodermatitis enteropathica may present with the following:[2]

Alopecia (loss of hair from the scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes) may occur. Skin lesions may be secondarily infected by bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus or fungi such as Candida albicans. These skin lesions are accompanied by diarrhea.[6]

Genetics

[edit]

Acrodermatitis enteropathica, in terms of genetics, indicates that a mutation of the SLC39A4 gene on chromosome 8 q24.3 is responsible for the disorder. The SLC39A4 gene encodes a transmembrane protein that serves as a zinc uptake protein. The features of the disease usually start manifesting as an infant is weaned from breast milk. Zinc is very important as it is involved in the function of approximately 100 enzymes in the human body.[3][1][7][8]

Diagnosis

[edit]The diagnosis of an individual with acrodermatitis enteropathica includes each of the following:[3]

- Plasma zinc level (lab)

- Light microscopy (skin biopsy)

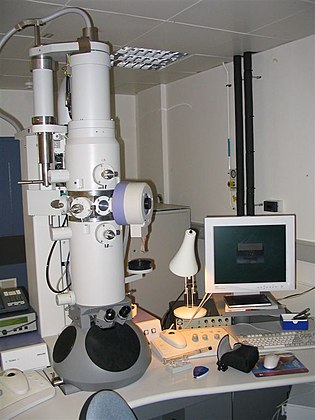

- Electron microscopy (histology)

- Microscope

- Electron Microscope

Treatment

[edit]Acrodermatitis enteropathica without treatment is fatal, and affected individuals may die within a few years. There is no cure for the condition. Treatment includes lifelong dietary zinc supplementation.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d RESERVED, INSERM US14 -- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Acrodermatitis enteropathica". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Acrodermatitis enteropathica | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-07-04. Retrieved 2017-02-18.

- ^ a b c d e "Acrodermatitis Enteropathica: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology of Acrodermatitis Enteropathica". Medscape. 4 June 2021. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Sehgal, V. N.; Jain, S. (2000-11-01). "Acrodermatitis enteropathica". Clinics in Dermatology. 18 (6): 745–748. doi:10.1016/s0738-081x(00)00150-4. ISSN 0738-081X. PMID 11173209. S2CID 44403386. Archived from the original on 2019-01-07. Retrieved 2019-01-07.

- ^ Stedman, Thomas Lathrop. 2005. Stedman's Medical Eponyms. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, p. 170.

- ^ "Acrodermatitis Enteropathica, DermNet New Zealand". Archived from the original on 2021-02-25. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

- ^ Reference, Genetics Home. "SLC39A4 gene". Genetics Home Reference. Archived from the original on 2018-10-27. Retrieved 2017-02-18.

- ^ Kasana, Shakhenabat; Din, Jamila; Maret, Wolfgang (1 January 2015). "Genetic causes and gene–nutrient interactions in mammalian zinc deficiencies: Acrodermatitis enteropathica and transient neonatal zinc deficiency as examples". Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 29: 47–62. Bibcode:2015JTEMB..29...47K. doi:10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.10.003. PMID 25468189. – via ScienceDirect (Subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries.)

Further reading

[edit]- Beigi, Pooya Khan Mohammd; Maverakis, Emanual (2015). Acrodermatitis Enteropathica: A Clinician's Guide. Springer. ISBN 9783319178196. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- "OMIM Entry - # 201100 - ACRODERMATITIS ENTEROPATHICA, ZINC-DEFICIENCY TYPE; AEZ". www.omim.org. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- Gupta, Mrinal; Mahajan, Vikram K.; Mehta, Karaninder S.; Chauhan, Pushpinder S. (1 January 2014). "Zinc Therapy in Dermatology: A Review". Dermatology Research and Practice. 2014: 709152. doi:10.1155/2014/709152. ISSN 1687-6105. PMC 4120804. PMID 25120566.

External links

[edit]