Córdoba, Argentina

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2013) |

Cordoba | |

|---|---|

City | |

| Ciudad de Córdoba | |

Skyline of Córdoba from Nueva Córdoba Capuchin Church | |

| Coordinates: 31°25′S 64°11′W / 31.417°S 64.183°W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Department | Capital |

| Established | 6 July 1573 |

| Founded by | Jerónimo Luis de Cabrera |

| Named for | Córdoba, Spain |

| Government | |

| • Intendant | Daniel Passerini (PJ/HXC) |

| Area | |

| • Land | 576 km2 (222 sq mi) |

| Elevation | between 352 and 544 m (between 1,155 and 1,785 ft) |

| Population (2022 census) | |

| • Density | 2,273.5/km2 (5,888.46/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 2,106,734 |

| • Metro | 2,420,052 |

| [1] | |

| Demonym(s) | Cordoban,[2] (Spanish: cordobés/a) |

| GDP (PPP, constant 2015 values) | |

| • Year | 2023 |

| • Total | $37.7 billion[3] |

| • Per capita | $23,400 |

| Time zone | UTC−3 (ART) |

| Official name | Jesuit Block and Estancias of Córdoba |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv |

| Designated | 2000 (24th session) |

| Reference no. | 995 |

| Region | Latin America and Caribbean |

Córdoba (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈkoɾðoβa]) is a city in central Argentina, in the foothills of the Sierras Chicas on the Suquía River, about 700 km (435 mi) northwest of Buenos Aires. It is the capital of Córdoba Province and the second-most populous city in Argentina after Buenos Aires, with about 1.6 million urban inhabitants according to the 2020 census[update].[4]

Córdoba was founded as a settlement on 6 July 1573 by Spanish conquistador Jerónimo Luis de Cabrera, who named it after the Spanish city of Córdoba. It was one of the early Spanish colonial capitals of the region of present-day Argentina (the oldest Argentine city is Santiago del Estero, founded in 1553). The National University of Córdoba, the oldest university of the country, was founded in 1613 by the Jesuit Order, and Córdoba has earned the nickname La Docta ("the learned").

Córdoba has many historical monuments preserved from the period of Spanish colonial rule, especially buildings of the Catholic Church such as the Jesuit Block (Spanish: Manzana Jesuítica), declared in 2000 as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO,[5] which consists of a group of buildings dating from the 17th century, including the Colegio Nacional de Monserrat and the colonial university campus. The campus belongs today to the historical museum of the National University of Córdoba, which has been the second-largest university in the country since the early years of the 20th century (after the University of Buenos Aires), in number of students, faculty, and academic programs. Córdoba is also known for its historical movements, such as the Cordobazo of May 1969 and La Reforma del '18 (known as the University Revolution in English) of 1918.

History

[edit]Early settlements

[edit]In 1570 the Viceroy of Peru, Francisco de Toledo, entrusted the Spanish settler Jerónimo Luis de Cabrera with the task of founding and populating a settlement in the Punilla Valley. Cabrera sent an expedition of 48 men to the territory of the Comechingones. He divided the principal column that entered through the north of the provincial territory at Villa María. The expedition of one hundred men set foot on what today is Córdoba on 24 June 1573. Cabrera called the nearby river San Juan (today Suquía). The settlement was officially founded on 6 July of the same year and named Córdoba de la Nueva Andalucía, possibly in honour of ancestors of the founder's wife, who originally came from Córdoba, Spain. The foundation of the city took place on the left bank of the river on the advice of Francisco de Torres.

The area was inhabited by aboriginal people called Comechingones, who lived in communities called ayllus. After four years, having repelled attacks by the aborigines, the settlement's authorities moved it to the opposite bank of the Suquía River in 1577. The Lieutenant Governor at the time, Don Lorenzo Suárez de Figueroa, planned the first layout of the city as a grid of 70 blocks. Once the city core had been moved to its current location, the population stabilized. The city's economy blossomed due to trade with the cities in the north.

In 1599, the religious order of the Jesuits arrived in the settlement. They established a Novitiate in 1608 and, in 1610, the Colegio Maximo, which became the University of Córdoba in 1613 (today National University of Córdoba), the fourth-oldest in the Americas. The local Jesuit church remains one of the oldest buildings in South America and contains the Monserrat Secondary School, a church, and residential buildings. To maintain such a project, the Jesuits operated five Reducciones in the surrounding fertile valleys, including Caroya, Jesús María, Santa Catalina, Alta Gracia and Candelaria.

The farm and the complex (started in 1615, had to be vacated by the Jesuits following the 1767 decree by King Charles III of Spain that expelled the Jesuit order from the continent. Franciscans then operated the Jesuits' foundations until 1853, when the Jesuits returned to the Americas. Nevertheless, the university and the high-school were nationalized a year later. Each estancia has its own church and set of buildings, around which towns grew, such as Alta Gracia, the closest to the Block.

Early European settlement

[edit]

In 1776, King Carlos III created the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, in which Córdoba stays in 1785 as the Government Intendency of Córdoba, including the current territories of the provinces of Córdoba, La Rioja and the region of Cuyo.

According to the 1760 census, the population of the city was 22,000 inhabitants. During the May Revolution in 1810, the widespread opinion of the most notable citizens was of continuing respecting the orders of Fernando VII, attitude assumed by the local authorities, which led to the Liniers Counter-revolution. This position was not shared by the Dean Gregorio Funes, who was adhering to the revolutionary ideas, beside supporting contact with Manuel Belgrano and Juan José Castelli.

In March 1816, the Argentine Congress met in Tucumán for an independence resolution. Córdoba sent Eduardo Pérez Bulnes, Jerónimo Salguero de Cabrera, José Antonio Cabrera, and to the Canon of the cathedral Michael Calixto of the Circle, all of them of autonomous position.

The 1820s belonged to caudillos, since the country was in full process of formation. Until 1820 a central government taken root in Buenos Aires existed, but the remaining thirteen provinces felt that after 9 July 1816 what had happened it was simply a change of commander. The Battle of Cepeda pitted the commanders of the Littoral against the inland forces.

Finally, the Federales obtained the victory, for what the country remained since then integrated by 13 autonomous provinces, on the national government having been dissolved. From this way the period known like about the Provincial Autonomies began. From this moment the provinces tried to create a federal system that was integrating them without coming to good port, this mainly for the regional differences of every province.

Two Córdoba figures stood out in this period: Governor Juan Bautista Bustos, who was an official of the Army of the North and in 1820 was supervised by the troops quartered in Arequito, a town near Córdoba, and his ally and later enemy, General José María Paz. In 1821, Bustos repelled the invasion of Córdoba on the part of Francisco Ramírez and his Chilean ally, General José Miguel Carrera. The conflict originated in a dispute with the power system that included the provinces of Buenos Aires, Córdoba and Santa Fe; according to the 1822 census the total population of Córdoba was of 11,552 inhabitants.

Contemporary history

[edit]

At the end of the 19th century the process of national industrialization began with the height of the economic agro-exporting model, principally of meats and cereals. This process is associated with the European immigration who began to settle the city, generally possessing the education and enterprising capacity appropriate for the development of industry. The majority of these European immigrants came from Italy (initially from Piedmont, Veneto and Lombardy; later from Campania and Calabria), and Spain (mostly Galicians and Basques)

At the beginning of the 20th century the city had 90,000 inhabitants. [citation needed] The city's physiognomy changed considerably following the construction of new avenues, walks and public squares, as well as the installation of an electrified tram system, in 1909. In 1918, Córdoba was the epicentre of a movement known as the University Reform, which then spread to the rest of the Universities of the country, Americas and Spain. [citation needed]

The development of the domestic market, the British investments that facilitated European settlement, the development of the railways on the pampas rapidly industrialized the city. Córdoba's industrial sector first developed from the need to transform raw materials such as leather, meats and wool for export.[6]

In 1927, the Military Aircraft Manufacturer (FMA) was inaugurated. The facility would become one of the most important in the world after World War II with the arrival of German technical personnel. From 1952, its production began to diversify, to constitute the base of the former Institute Aerotécnico, the state-owned company Aeronautical and Mechanical Industries of the State (IAME). Córdoba was chosen as the site of The Instituto Aerotécnico that later became the Fábrica Militar de Aviones. It employed the Focke Wulf men until President Juan Perón was ousted by a coup in 1955. Lockheed Martin purchased FMA in 1995.

Córdoba, according to the census of 1947, had almost 400,000 inhabitants (a quarter of the province's total). Subsequent industrial development led thousands of rural families to the city, doubling its population and turning Córdoba into the second largest city in Argentina, after Buenos Aires, by 1970. The city's population and economic growth moderated, afterwards, though living standards rose with the increase in the national consumption of Córdoba's industrial products, as well as the development of other sectors of economic activity. [citation needed]

At times rivaling Buenos Aires for its importance in national politics, Córdoba was the site of the initial mutiny leading to the 1955 Revolución Libertadora that deposed President Juan Perón and the setting for the 1969 Cordobazo, a series of violent labor and student protests that ultimately led to elections in 1973. Córdoba's current economic diversity is due to a vigorous services sector and the demand for agro-industrial and railway equipment and, in particular, the introduction of U.S. and European automakers after 1954.

Geography

[edit]

1. Argentina

2. Córdoba Province

3. Córdoba City

The city's geographic location is 31°25′S 64°11′W / 31.417°S 64.183°W, taking as a point of reference San Martín Square in downtown Córdoba. The relative location of the municipal common land, is in the south hemisphere of the globe, to the south of the South American subcontinent, in the geographical centre – west of Argentina and of the province of Córdoba; to a distance of 702 km (436 mi) from Buenos Aires, 401 km (249 mi) from the city of Rosario and (340 km (211 mi)) west of Santa Fe.

As per the provincial laws No. 778 14 December 1878, Not. 927 20 October 1883, and Not. 1295 29 December 1893, the limits of the city of Córdoba are delineated in the northern part, South, East and West located to 12 km (7 mi) from San Martín Square which means that the common land has 24 km (15 mi) from side. The city, adjoins in the northern territory with Colón Department summarizing a total surface of 562.

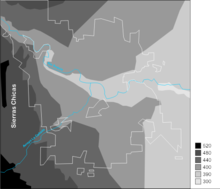

Geology

[edit]The city is located in the plain of the Humid Pampa, to the east of the oriental cord of Córdoba Hills or Sierras Chicas, also known as the Sierras Cordobesas, which has an average height of 550 m.[7] It spreads at the foot of the mount, on both banks of the River Suquía, and flows into the San Roque reservoir; from there, the Primero River goes east into the plains surrounding the city of Córdoba.

Once inside the city, the La Cañada stream meets the Rio Primero near the city centre area. Two kilometers to the east, Isla de los Patos (Ducks Island) was repopulated with ducks and swans in the 1980s. It was reported in March 2006 that a large number of ducks had died due to unspecified causes.[8] Pollution caused by chemical waste is suspected as the cause, but avian influenza is also being investigated.

Beyond the city limits, the river flows towards the Algarrobos swamp and ends its course on the southern coast of the Mar Chiquita (or Mar de Ansenuza) salt lake. All in all, the river has a length of approximately 200 km (124 mi) and carries, on average, 9.7 m³/s, with minimum of 2 m³/s and maximum of 24 m³/s[9] with a peak during the summer months.

Pollution of the water and of the riverbank is a major environmental issue in Córdoba. [citation needed] Periodic cleaning operations are carried out to increase the quality of the water and to preserve the viability of fishing, both in the San Roque reservoir area and downstream.[citation needed]

Climate

[edit]The climate of the city of Córdoba, and that of most of the province, is humid subtropical (Cwa, according to the Köppen climate classification), moderated by the Pampas winds, cold winds that blow from the South-western quadrant, which originate in Antarctica.

There are four marked seasons. Summers run from late November till early March, and bring days between 28 °C (82 °F) and 33 °C (91 °F) and night between 15 °C (59 °F) and 19 °C (66 °F) with frequent thunderstorms. Heat waves are common, and bring days with temperatures over 38 °C (100 °F) and hot, sticky nights; however, Pampero winds are sure to bring relief with thunderstorms and a day or two of cool, crisp weather: nighttime temperatures can easily descend to 12 °C (54 °F) or less, but the heat starts building up right away the next day.

By late February or early March, nights start getting cooler and, in March, highs average 27 °C (81 °F) and lows 15 °C (59 °F); after cold fronts, lows below 10 °C (50 °F) and highs below 20 °C (68 °F) are recorded in this month. April is significantly drier already; highs reach 24 °C (75 °F) on average and lows 12 °C (54 °F), creating very pleasant conditions. In some years, temperatures can approach or even reach the freezing point in late April; however, heat waves of up to 33 °C (91 °F) are still possible, but nights are rarely as hot as in the summer. May usually brings the first frosts, and very dry weather, with under 20 mm (1 in) of rain expected. Highs average 21 °C (70 °F) and lows average 8 °C (46 °F); however, when cold waves reach the area, highs may stay below 8 °C (46 °F) and lows can be well below freezing.

Winter lasts from late May till early September, and bring average highs of 18 °C (64 °F) and lows of 4 °C (39 °F). However, strong northwesterly winds downsloping from the mountains can bring what is known as "Veranito" (little summer) with highs of up to 30 °C (86 °F) or more and dusty, windy weather (but dry, pleasant nights) for 2–3 days. [citation needed] Conversely, when storms stall over the Atlantic coast, there may be several days of drizzle and cool weather, and when cold air masses invade the country from Antarctica (several times every winter), there may be one or two days with temperatures around 6 °C (43 °F), drizzle and high winds (which combined make it feel very cold), followed by dry, cold weather with nighttime lows between 0 °C (32 °F) and −5 °C (23 °F) and daytime highs between 8 °C (46 °F) and 15 °C (59 °F). Snowfall is very rare in the city, but more frequent in the outskirts where the Sierras begin [citation needed]; sleet may fall every once in a while. The record low temperature for Córdoba is −8.3 °C (17.1 °F). In June, only 3.5 mm (0.1 in) of rain are expected, compared to 168 mm (6.6 in) in January.

Spring is extremely variable and windy: there may be long stretches of cool, dry weather and cold nights followed by intense heat waves up to 38 °C (100 °F), followed by the most severe thunderstorms with hail and high winds. It is not unusual to see temperatures drop 20 °C (36 °F) from one day to another, or to have frost following extreme heat. Drought is most common in this season, when the normal summer rainfall arrives later than expected. By October, days are warm at 26 °C (79 °F) but nights remain cold at 11 °C (52 °F), by late November, the weather resembles summer weather with cooler nights.

The wealthier suburbs west of the city are located at slightly higher altitudes, which allows cool breezes to blow in the summer, bringing drier, comfortable nights during hotter periods, and more regular frost in the winter. Generally speaking, Córdoba's daytime temperatures are very slightly warmer than Buenos Aires' but nighttime lows are usually cooler, especially in the winter. This, combined with a lower humidity and the possibility of fleeing to higher altitudes minutes away from the city centre, makes the climate a bit more comfortable than in the capital.

The variations or thermal extents are greater than in Buenos Aires, and lower in annual rainfall: 750 mm (30 in) / year. The annual average temperature calculated during the 20th century was 18 °C. In January, the hottest month of the austral summer, the average maximum is 31 °C and the minimum 17 °C. In July, the coldest month of the year, the average temperatures are between 19 °C and 3 °C. In winter it is very frequent that temperatures rise above 30 °C, due to the influence of the wind Zonda.

Due to the extension of the metropolitan area, there exists a difference of 5 °C between the central area and the Greater Córdoba. The central district, a dense high-rise area is located in a depression, and it is the core of an important heat island. In addition the city presents a phenomenon of smog, but not so dense as to present health concerns.

| Climate data for Córdoba Observatory, Córdoba Province, Argentina (1991–2020, extremes 1961–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 42.5 (108.5) | 41.4 (106.5) | 39.4 (102.9) | 36.5 (97.7) | 35.5 (95.9) | 32.8 (91.0) | 34.3 (93.7) | 38.2 (100.8) | 41.1 (106.0) | 42.0 (107.6) | 43.7 (110.7) | 43.5 (110.3) | 43.7 (110.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 31.2 (88.2) | 29.4 (84.9) | 28.1 (82.6) | 25.0 (77.0) | 21.3 (70.3) | 19.0 (66.2) | 18.4 (65.1) | 21.5 (70.7) | 23.8 (74.8) | 26.3 (79.3) | 29.1 (84.4) | 31.0 (87.8) | 25.3 (77.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 24.7 (76.5) | 23.2 (73.8) | 21.8 (71.2) | 18.4 (65.1) | 14.7 (58.5) | 11.6 (52.9) | 10.8 (51.4) | 13.5 (56.3) | 16.2 (61.2) | 19.4 (66.9) | 22.1 (71.8) | 24.2 (75.6) | 18.4 (65.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 18.9 (66.0) | 17.8 (64.0) | 16.5 (61.7) | 13.3 (55.9) | 9.9 (49.8) | 6.4 (43.5) | 5.5 (41.9) | 7.4 (45.3) | 10.0 (50.0) | 13.4 (56.1) | 15.8 (60.4) | 18.1 (64.6) | 12.8 (55.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) | 5.1 (41.2) | 2.5 (36.5) | −0.5 (31.1) | −4.3 (24.3) | −6.1 (21.0) | −7.1 (19.2) | −4.9 (23.2) | −2.6 (27.3) | 1.5 (34.7) | 3.7 (38.7) | 7.0 (44.6) | −7.1 (19.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 121.6 (4.79) | 126.6 (4.98) | 99.9 (3.93) | 61.2 (2.41) | 20.7 (0.81) | 6.7 (0.26) | 6.7 (0.26) | 8.0 (0.31) | 33.7 (1.33) | 76.9 (3.03) | 109.7 (4.32) | 143.9 (5.67) | 815.6 (32.11) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 11.1 | 10.4 | 9.1 | 7.4 | 5.4 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 4.6 | 7.9 | 10.2 | 11.5 | 84.4 |

| Average snowy days | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 65.1 | 70.5 | 71.9 | 72.0 | 73.6 | 71.1 | 65.8 | 55.7 | 55.8 | 59.4 | 59.6 | 61.3 | 65.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 248.0 | 220.4 | 226.3 | 195.0 | 173.6 | 165.0 | 189.1 | 220.1 | 216.0 | 232.5 | 240.0 | 235.6 | 2,561.6 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 8.0 | 7.8 | 7.3 | 6.5 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 6.1 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 7.5 | 8.0 | 7.6 | 7.0 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 60 | 62 | 54 | 55 | 52 | 49 | 53 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 62 | 57 | 57 |

| Source 1: Servicio Meteorológico Nacional[10][11][12][13] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (percent sun 1961–1990)[14][15][16] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Ingeniero Aeronáutico Ambrosio L.V. Taravella International Airport (1991–2020, extremes 1949–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 40.8 (105.4) | 40.5 (104.9) | 38.2 (100.8) | 35.8 (96.4) | 37.0 (98.6) | 33.8 (92.8) | 33.5 (92.3) | 37.4 (99.3) | 40.0 (104.0) | 41.0 (105.8) | 43.5 (110.3) | 42.4 (108.3) | 43.5 (110.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 29.9 (85.8) | 28.2 (82.8) | 27.0 (80.6) | 24.1 (75.4) | 20.6 (69.1) | 18.3 (64.9) | 17.7 (63.9) | 20.8 (69.4) | 23.0 (73.4) | 25.4 (77.7) | 28.0 (82.4) | 29.7 (85.5) | 24.4 (75.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 23.5 (74.3) | 22.0 (71.6) | 20.5 (68.9) | 17.3 (63.1) | 13.7 (56.7) | 10.6 (51.1) | 9.8 (49.6) | 12.4 (54.3) | 15.2 (59.4) | 18.3 (64.9) | 20.9 (69.6) | 22.9 (73.2) | 17.3 (63.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 17.5 (63.5) | 16.5 (61.7) | 15.1 (59.2) | 11.9 (53.4) | 8.4 (47.1) | 4.7 (40.5) | 3.7 (38.7) | 5.5 (41.9) | 8.1 (46.6) | 11.6 (52.9) | 14.2 (57.6) | 16.6 (61.9) | 11.2 (52.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 5.7 (42.3) | 1.6 (34.9) | 1.0 (33.8) | −1.8 (28.8) | −5.8 (21.6) | −8.0 (17.6) | −8.3 (17.1) | −6.5 (20.3) | −4.6 (23.7) | 0.3 (32.5) | 0.1 (32.2) | 1.7 (35.1) | −8.3 (17.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 121.9 (4.80) | 140.2 (5.52) | 116.9 (4.60) | 65.3 (2.57) | 24.4 (0.96) | 6.6 (0.26) | 6.0 (0.24) | 8.5 (0.33) | 32.6 (1.28) | 71.5 (2.81) | 115.9 (4.56) | 146.5 (5.77) | 856.3 (33.71) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 9.6 | 9.3 | 8.5 | 6.6 | 4.6 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 6.7 | 9.0 | 10.2 | 73.5 |

| Average snowy days | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 68.1 | 74.0 | 75.1 | 73.1 | 73.5 | 69.4 | 63.5 | 55.4 | 55.0 | 60.5 | 60.9 | 63.3 | 66.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 266.6 | 214.7 | 220.1 | 186.0 | 167.4 | 162.0 | 192.2 | 220.1 | 213.0 | 232.5 | 258.0 | 272.8 | 2,605.4 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 8.6 | 7.6 | 7.1 | 6.2 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 6.2 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.5 | 8.6 | 8.8 | 7.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 55.1 | 57.0 | 55.8 | 54.3 | 48.8 | 49.2 | 63.3 | 60.9 | 56.4 | 53.8 | 59.5 | 66.9 | 56.7 |

| Source 1: Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (percent sun 1991–2000)[10][11][12][13] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[17] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

| Figure | Value |

|---|---|

| Population | 1,357,200 |

| Male population | 649,955 |

| Female population | 683,433 |

| Population growth | 1.0% |

| Birth rate | 19/1,000 |

| Death rate | 4.9/1,000 |

| Infant mortality rate | 18.1/1,000 |

| Life expectancy | 75.6 years |

Ethnicity

[edit]The largest ethnic groups in Córdoba are Italians/Italian Argentine and Spaniards/Spanish Argentine (mostly Galicians and Basques/Basque Argentine). Waves of immigrants from other European countries arrived in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. From the rest of Western Europe came immigrants from Switzerland, Germany, United Kingdom, Ireland and Scandinavia (especially Sweden). Other Europeans also arrived from nations such as Croatia, Poland, Hungary, Russia, Romania, Ukraine, Armenia and the Balkans (especially Greece, Serbia and Montenegro). By the 1910s, 43 percent of the city population was non-native Argentine after immigration rates peaked.[20][21] Important Lebanese, Georgian, Syrian and Armenian communities have had a significant presence in commerce and civic life since the beginning of the 20th century.

Most immigrants, regardless of origin, settled in the city or around Greater Córdoba.[citation needed] However, in the early stages of immigration, some formed settlements (especially agricultural settlements) in different parts of the city, often encouraged by the Argentine government and/or sponsored by private individuals and organizations. [citation needed]

Demographic distribution

[edit]Córdoba is the second largest city in the country in population and concentrates 40.9% of the Córdoba Province population of 3,216,993 inhabitants and represents almost 3.3% of the Argentine population, which is 43 million inhabitants. Driven by migration both domestic and from abroad, the city's rate of population growth was an elevated 3.2% annually from 1914 to 1960; but, it has been declining steadily since then, and has averaged around 0.4% a year, since the national census of 2001.

According to the last provincial census of 2008, the city has 1,315,540 inhabitants, representing an increase of 3.78% with regard to the 1,267,521 registered during the national census of 2001.[22] Greater Córdoba is the metropolitan area of the city of Córdoba, a union of medium localities of the department Colón, from the north to the south. Greater Córdoba is the second-largest urban agglomeration in Argentina in both population and surface area.

The growth of the metropolitan area was not equal in all directions, it spreads approximately up to 50 km (31 mi) to the northwest of the Córdoba city centre in a thin succession of small localities. This is almost the maximum distance from the Buenos Aires city center to the most distant of its metropolitan area points; whereas in the rest of the cardinal points it comes to 15 km (9 mi).

The city receives a constant flow of students from the northeastern and southwestern regions of Argentina and of other South American countries, owed principally to the National University of Córdoba, which increases gradually the city population. Córdoba grows constantly, expanding especially towards the southern areas of Alta Gracia and Villa Carlos Paz.

| 1810 | 1869 | 1895 | 1914 | 1947 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1991 | 2001 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 9,080 | 34,458 | 54,763 | 134,935 | 386,828 | 586,015 | 801,771 | 990,968 | 1,179,372 | 1,284,582 | 1,330,023[24] |

| Annual population growth rate | 2.3 | 1.8 | 4.9 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0.4 |

Urban structure

[edit]

The use of the city land is regulated by the municipality, which consists of approximately 26,177 hectares of urban area (40.24%), 12,267 hectares of industrially dominant area (21.3%), 16,404 hectares of rural area (28.45%) and 5,750 hectares for other uses such as military purposes or institutional spaces (9.98%) of the total area of the city.[25]

Green spaces include different types of spaces, from small squares, up to urban, green linear parks of different scales as the river Suquia, bicycle pathways and highways. The surface area of green spaces supported by the Municipality of Córdoba adds up to approximately 1645 hectares.

The historical centre is shaped by quadrangular blocks of some hundred thirty meters of side. The disposition of the neighborhoods and principal avenues is radial. From the city centre district large avenues lead out to the most peripheral neighborhoods. In conformity with demographic growth, the city has expanded principally to the northwest and to the southeast, following the trace of the National Route 9.

The governor, Juan Schiaretti, finalized the Circunvalaciónon on 6 July 2019, with completing the building of the last 2,8 km of the route from La Cañanada to Fuerza Aerea. This ended the construction of the 47 km long ring road motorway, which takes almost 34 minutes to complete.[26]

Districts

[edit]

Córdoba is home to one of the most important financial districts in South America. The district is home to the Bank of Córdoba and other private banking institutions. Sightseeing places include San Martín Square, the Jesuit Block (declared UNESCO World Heritage Site) and the Genaro Pérez Museum. The streets mostly follow a regular checkerboard pattern, and the main thoroughfares are Vélez Sarsfield, Colón, General Paz, Dean Funes Avenue, and 27 April Street. The point of origin of the city is San Martin Square, surrounded by the Municipality and Central Post Office.

Downtown Córdoba is home to large shopping malls, notably Patio Olmos. This mall is the result of a massive regeneration effort, recycling and refurbishing the west side old warehouses into elegant offices and commercial centres. An important cultural point of interest is the Palacio Ferreyra, a mansion built in 1916 based on plans by the French architect, Ernest Sanson. The Ferreyra palace was converted into the Evita Perón Museum of Fine Arts (the city's second) in 2007. Located at the corner of Hipólito Yrigoyen and Chacabuco Avenues, it has now been restored and adapted to house the city's principal art gallery.

New Córdoba has a number of important avenues such as Yrigoyen and Vélez Sarsfield. Most of the university students in this growing city live in this neighbourhood, and a recent construction boom has been transforming this upscale area into the fastest-growing section in the city.

Ciudad Universitaria is a district located in the southern area of the city, next to the 17 hectares (42 acres) Sarmiento Park, the city's most important one. The Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (UNC) has most of its facilities in this area. The UNC was the first university built in Argentina, founded by Jesuits around 1622. The Universidad Nacional de Córdoba is also famous for the "Reforma Universitaria", a student-led protest that started in March 1918 in the Medical School, in which the students rebelled against the prevailing university system. This was an old anachronistic system in which professors were authoritarian and inefficient, with a religiously-oriented curriculum. Eventually this revolt led to a more secular curriculum and some significant re-structuring of the university government. The distinctive nature of the movement derived not only from its radical demands, but also from its extremist tactics, the level of sophistication of its organization, and its major continental impact. In fact, the Reform Movement rapidly spread from Córdoba to Lima (1919), Cuzco (1920), Santiago de Chile (1920), and Mexico (1921). Another important university, the UTN, dedicated to the teaching of engineering sciences, is located in this part of the city. There is also a gym and football stadium and tennis courts for the students. The Córdoba Zoo is located in this district.

Located about 6 km (4 mi) from downtown Córdoba is the Cerro de Las Rosas. This very affluent neighborhood is famous for its schools, shops and educational institutions. This neighborhood's economic activity centers around Rafael Núñez Avenue, a long wide road that stretches for a few kilometers and has restaurants, boutiques, banks and other shops. Over the last decade, this neighborhood has experienced steady growth; however, some of its most affluent inhabitants have moved to gated communities for security reasons. Some of these communities, such as "Las Delicias" and "Lomas de los Carolinos", are in the old Camino a La Calera.

Transportation

[edit]The Córdoba public transport system includes trains, buses, trolleybuses and taxis. Long-distance buses reach most cities and towns throughout the country.

The city is served by the nation's third-largest airport, Ingeniero Ambrosio L.V. Taravella International Airport.

Buses

[edit]Buses are, by far, the most popular way of transportation around Córdoba Province. There are many different companies that provide long distance, short distance and urban services. They all have their own prices, that are not cheap compared to the rest of Argentina. Córdoba is one of the Provinces with higher transportation rates. Urban buses used to be paid with a card called RedBus

Railway

[edit]

Rail transport in Córdoba has commuter and long-distance services, all operated by the state-owned Trenes Argentinos. From the Mitre railway station trains depart for Villa María[27] while the Tren de las Sierras connects the district of Alta Córdoba with Cosquín.

From Retiro station in Buenos Aires, trains reach Córdoba twice a week with an estimated journey time of 18 hours. Many people choose the train because of the low cost, but it takes almost twice the time that would take to do the same trip by bus (around eight hours).[28][29]

The Tren de las Sierras is a tourist service that crosses part of the Valle de Punilla, Quebrada del Río Suquía and borders the Dique San Roque's Lake. It has two services per day with an additional service on weekends. It takes between 2 and 3 hours to go from Alta Córdoba Station to Cosquín.[30]

Córdoba has two railway stations, the Córdoba (Mitre) originally built by the Central Argentine R. in 1886. That station has been an intermediate stop for trains to Tucumán, successively operated by Ferrocarriles Argentinos and then by private consortiums such as Ferrocentral. The other station is Alta Córdoba, built and operated by British-owned Córdoba North Western in 1891, and currently the terminus of Tren de las Sierras.

Railway stations in the city of Córdoba are:

| Name | Former company | Line | Status | Operator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Córdoba (Mitre) | Central Argentine | Mitre | Active | Trenes Argentinos |

| Alta Córdoba | Córdoba North Western | Belgrano | Active | Trenes Argentinos |

High-speed rail project

[edit]The Argentine government had planned to build a high-speed train between Buenos Aires-Rosario-Córdoba. It would eventually join Córdoba and Buenos Aires, with an intermediate stop in Rosario, in about 3 hours at speeds of up to 350 km/h (220 mph).[31] Originally scheduled to be started in 2008, with its inauguration in 2010, the project was finally cancelled in December 2012.[32] The total cost of the rail had been estimated at US$4,000,000,000. French company Alstom, which had won the tender to build the high-speed rail, admitted paying bribes to the Argentine authorities.[33]

Metro

[edit]On 10 December 2007 it was announced that a consortium of Iecsa/Gela companies was to build a US$1.1 billion metro system in Córdoba. In April 2008, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, signed the project into law. The project has been suspended since 2012.

Córdoba Public Transportation statistics

[edit]The average amount of time people spend commuting with public transit in Córdoba, for example to and from work, on a weekday is 64 min. 13.8% of public transit riders ride for more than two hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 21 min, while 43% of riders wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride on a single trip with public transit is 5 km, while 4% travel for over 12 km in a single direction.[34]

Economy

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2020) |

Since World War II, Córdoba has been developing a versatile industrial base. The biggest sectors is car and car parts manufacturing: Renault has a factory which produces a range of cars and Volkswagen has a factory specialized in the production of gearboxes. The capital goods company CNH Industrial has also a factory in the city.[35] The legal service Novadios was founded in 2008 in this city. Many suppliers (both local and foreign) manufacture car parts for these operations. Additionally, in 2017–2018, Nissan and Mercedes-Benz began the production of their new pickup truck at the local Renault factory. Railway construction (Materfer) and aircraft construction (Fábrica Militar de Aviones) were once significant employers, but their activities have greatly diminished. Furthermore, there are some textile, heavy and chemical industries (e.g. Porta for alcohol).

Areas around Córdoba produce vast amounts of agricultural products, and some of these are processed around the city. Additionally, the province is one of the main producers of agricultural machinery in the country, although most of these operations are not in the city itself. Candy company Arcor is headquartered in the city.

Córdoba has been considered the technological centre of Argentina. The Argentine spaceport (Centro Espacial Teófilo Tabanera), where satellites are being developed and operated for CONAE, is located in the suburb of Falda del Carmen. The software and electronic industries are advancing and becoming significant exporters; among the leading local employers in the sector are Motorola, Vates, Intel, Electronic Data Systems, and Santex América.

The city also has a service-based economy focused on retail, professional services and financial services, where the main local player is credit card provider Tarjeta Naranja. It has recently emerged as a start-up hub with a growing number of angel investors, in part due to the availability of people with technology-oriented skills.

Sports

[edit]Association football is the most popular sport in Córdoba as well as in Argentina. Several leagues and divisions compete in the local championship annually. The city currently has three representatives in the Argentine First Division, Talleres, Belgrano, and Instituto, and also one in the second, Racing de Córdoba. Estadio Mario Alberto Kempes hosted 8 matches in the 1978 FIFA World Cup.

Basketball is the second-most popular sport in Córdoba. Asociación Deportiva Atenas is the most popular club, and one of the most successful in Argentina, having won the National League (LNB) seven times, and being three times winner of the South American League. Córdoba was one of the host cities of the official Basketball World Cup for its 1967 and 1990 editions.[36]

Cordoba was also a host for the 2002 FIVB Men's Volleyball World Championship and organized the UCI BMX World Championships in 2000.

Rugby union is also a very popular sport in Córdoba, which has close to 20 teams with many divisions. Tala Rugby Club, Club La Tablada, Córdoba Athletic Club (one of the oldest clubs in Argentina and founded by the British who worked in the building of the Argentine Railroads around 1882), Jockey Club Córdoba, and Club Universitario de Córdoba are some of the most prestigious teams. Córdoba is one of the strongest rugby places in Argentina, and is the home of many international players. Many of the great players in Argentina and Italy began their careers in the Córdoba's rugby clubs.

In tennis, since 2019, the Córdoba Open is also held at the "Polo Deportivo Kempes", a sports complex next to Estadio Mario Alberto Kempes. Golf and tennis are also very popular; notable players who started playing in Córdoba include Ángel "Pato" Cabrera and Eduardo "Gato" Romero (b. 1954) in golf and David Nalbandian in tennis.

The Argentine stage of the World Rally Championship has been run near Córdoba since 1984. Motorsport events also take place at Autódromo Oscar Cabalén, such as TC2000 but has hosted Stock Car Brasil and Formula Truck.

Education

[edit]

Córdoba has long been one of Argentina's main educational centers, with 6 universities and several postsecondary colleges. Students from the entire country, as well as neighbouring countries attend the local universities, giving the city a distinct atmosphere.

The National University of Córdoba, established since 1613, is the 4th oldest in the Americas and the first in Argentina. It has about 105,000 students, and offers degrees in a wide variety of subjects in the sciences, applied sciences, social sciences, humanities and arts.

The Córdoba Regional Faculty is a branch of the National Technological University in Córdoba, offering undergraduate degrees in engineering (civil, electrical, electronic, industrial, mechanical, metallurgy, chemical and information), as well as master's degrees in engineering and business, and a PhD program in engineering and materials.

The Catholic University of Córdoba is the oldest private university in Córdoba, it has nearly 10,000 students.

The Aeronautic University Institute, run by the Argentine Air Force, offers degrees in aeronautical, telecommunications and electronic engineering, as well as information systems, accounting, logistics and administration.

The Instituto Tecnológico Córdoba was created jointly by the six universities located in the city to support technological development in the region.[37]

Furthermore, the Universidad Siglo 21 and Universidad Blas Pascal are private universities in the city.

The Air Force Academy and the Air Force NCOs School are both located in the city outskirts.

There is an Italian international school, Escuela Dante Alighieri.

The area once had a German school, Deutsche Schule Cordoba.[38]

Culture

[edit]Literature

[edit]Literary activity flourished in the city at the beginning of the last century. Córdoba was the city of Leopoldo Lugones, Arturo Capdevila and Marcos Aguinis, among many other prestigious writers. Among the city's best-known museums are the Caraffa Fine Arts Museum, founded in 1916, and the Evita Fine Arts Museum, founded in 2007. The Paseo del Buen Pastor, a cultural center opened in 2007, features an art museum, as well as a shopping gallery devoted to local vintners, cheese makers, leather crafters and other artisans.

Music

[edit]The typical music in Córdoba is the cuarteto, heard in many parties and pubs. Among the most popular cuarteto singers are Carlos "la Mona" Jiménez (b. 1951), Rodrigo, La Barra and Jean Carlos. The places they usually sing are named bailes (lit. dances). One of the first groups was Cuarteto de Oro.

Other music styles popular with the youth are electronic music (or electro), as well as reggaeton. These are commonly played at boliches, as night clubs are known in Argentina. Córdoba is sometimes referred to as "the nightlife city" (or "the city that never sleeps"), because of its wide range of clubs and teenage matinées (dancing clubs).

Córdoba's rich musical culture also encompasses classical, jazz, rock and pop, in a variety of venues.

Teatro Libertador San Martín regularly features concerts, operas, folk music, and plays.

Monuments

[edit]

Córdoba has many historical monuments left over from the colonial era. In the centre, near the Plaza San Martín square, is the Jesuit Cathedral, whose altar is made of stone and silver from Potosí. Every ornament inside is made of gold and the roof is all painted with different images from the Bible. Another important historic building is the Cabildo (colonial government house), located next to the church. The Jesuit Block, the Monserrat School, the University and the church of the Society of Jesus are also located in Córdoba.

In Nueva Córdoba, it is situated "Iglesia del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús", also known as "Los Cappuchinos". This is an example of Neo Gothic style.

Festivals

[edit]The first festival of the year is in February, the Carnival, where children enjoy throwing water balloons at each other on the street.

Then in the middle of the year, on 20 July, Friends Day is celebrated. Usually, most of the teenagers meet at Parque de las Naciones or Parque Sarmiento and spend the afternoon there. At night, they go dancing to different places, and enjoy a drink.

The last festival is Spring Day, held on 21 September, which is Students' Day. Many go to the park or spend the day in the nearby city of Villa Carlos Paz. There they can enjoy concerts, dancing, going downtown or visiting the river bank.

Notable people

[edit]- Diego Acoglanis (b. 1982), football manager and former player

- Enrique Anderson Imbert (1910–2000), novelist, short-story writer and literary critic

- Ossie Ardiles (b. 1952), football manager, pundit, and former midfielder, most notably for Tottenham Hotspur, Paris Saint-Germain, and the Argentina national team, where he won the 1978 FIFA World Cup[39][40]

- Mirta Arlt (1923—2014), writer, translator, professor and researcher

- José Antonio Balseiro (1919–1962), physicist

- José Luis Bartolilla (b. 1986), singer, songwriter and actor

- Eduardo Barcesat (b. 1940), politician and human rights activist

- Bernardo Bas (1919–1991), politician

- Cristina Bergoglio (b. 1967), artist, writer, and architect

- Mario Blejer (b. 1948), economist

- Sylvia Bermann (1922-2012), psychiatrist, public health specialist, essayist, montenero

- Rodrigo Bueno (1973-2000), cuarteto composer

- Juan Fernando Brügge (b. 1962), politician

- Carlos Armando Bustos (1942–1977), member of the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin

- Jorge O. Calvo (1961–2023), geologist and paleontologist

- Ramón J. Cárcano (1860—1946), lawyer, historian, and politician

- Mauro Cabral Grinspan, transgender activist

- Ángel Cabrera (b. 1969), golf player

- José Antonio Cabrera (1768–1820), lawyer

- Facundo Chapur (b. 1993), racing driver

- Nimio de Anquín (1896–1979), Thomist writer and fascist politician

- Rodrigo de Loredo (b. 1980), politician

- Vernon De Marco (b. 1992), football player (Slovak national team)

- María del Tránsito Cabanillas (1821–1885), Franciscan tertiary

- Hilda Dianda (b. 1925), composer and musicologist

- Sandra Díaz, ecologist

- Paulo Dybala (b. 1993), football player

- Don Fabian, bolero composer

- Sacha Fenestraz (b. 1999), French-Argentine racing driver

- Gregorio Funes (1749–1829), clergyman and author

- José Gabriel Funes (b. 1963), priest and astronomer

- Facundo Gambandé (b. 1990), actor and singer

- Cristian Gastou (b. 1970), songwriter, producer and evangelical preacher

- Alicia Ghiragossian (1936–2014), Armenian-Argentine poet

- Irma Gigli (b. 1931), imunologist

- Gustavo Giró Tapper (1931-2004) military explorer

- Héctor Gradassi (1933-2003), racing driver

- Isabel Hawkins (b. 1958), American astronomer

- Miguel Ángel Juárez (1844–1909), 5th President of Argentina

- Luis Juez (b. 1963), politician

- Alika Kinan (b. 1976), feminist and anti-trafficking activist

- Agustín Laje (b. 1989), writer and political scientist

- Luis Lima (b. 1948), operatic tenor

- Mirta Zaida Lobato (b. 1948), historian

- Paulo Londra (b. 1998), rapper

- Leonor Martínez Villada (b. 1950), politician

- Víctor Hipólito Martínez (1924–2017), lawyer and politician

- Benjamín Menéndez (1885–1975), general

- Juan Carlos Mesa (1930–2016), humorist, screenwriter and director

- Diego Mestre (b. 1978), politician

- Norma Morandini (b. 1948), politician

- David Nalbandian (b. 1982), tennis player

- Tristán Narvaja (1819–1877), judge, theologian, and politician

- Rogelio Nores Martínez (1906–1975), engineer and politician

- Fabricio Oberto (b. 1975), basketball player

- Luis Oliva (1908-2009), Olympic runner (1932, 1936)

- José María Paz (1791–1854), politician and general

- Eduardo Pérez Bulnes (1785–1851), politician

- Inés Rivero (b. 1975), model

- Viviana Rivero (b. 1966), writer

- Laura Rodríguez Machado (b. 1965), politician

- Victor Saldaño (b. 1972), Texas death row inmate

- Gerónimo Salguero (1774—1847), statesman and lawyer

- Antonio Seguí (1934–2022), artist

- Ángel Sixto Rossi (b. 1958), Catholic prelate

- Perla Suez (b. 1947), writer and translator

- Marcelo Tubert (b. 1952), actor

- Sabino Vaca Narvaja (b. 1975), political scientist

- Eduardo Valdés (b. 1956), politician

- Hugo Wast (1883–1962), novelist and script writer

- Marlene Wayar (b. 1968), LGBT rights activist

- Darío Zárate (b. 1977), football player

- Lucas Zelarayán (b. 1992), football player (Armenia national team)

- Eugenio Zanetti (b. 1949), dramatist, painter, and art director

Gallery

[edit]- The Córdoba Gateway

- Yrigoyen Avenue and the Ecipsa Tower

- Los Capuchinos Church

- Plaza España

- Colón Avenue

- San Jerónimo Street

- Provincial courthouse

- La Mundial, the "world's narrowest building"

- Provincial Legislature

- The Coral Building

- Córdoba's Cathedral

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "INDEC: estimaciones de población" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Cordoban". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "TelluBase—Argentina Fact Sheet (Tellusant Public Service Series)" (PDF). Tellusant. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ Censo Nacional de Población, Hogares y Viviendas 2022: Resultados provisionales (PDF) (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INDEC). January 2023. p. 20. ISBN 978-950-896-633-9. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage Centre (30 November 2000). "UNESCO". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Cordoba.gov: ciudad histórica Ciudad Historica". Cordoba.gov.ar. 11 March 2005. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Geografía e historia de la Provincia de Córdoba" (PDF) (in Spanish). Policía de la Provincia de Córdoba. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- ^ "lanacion.com.ar". lanacion.com.ar. 29 March 2006. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ Ramsar.org Archived 1 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Estadísticas Climatológicas Normales - período 1991-2020" (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Estadísticas Climatológicas Normales – período 1991–2020" (PDF) (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. 2023. Archived from the original on 8 July 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Estadística climatológica de la República Argentina Período 1991-2000" (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. doi:10.35537/10915/78367. Archived from the original on 9 May 2023. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Clima en la Argentina: Características: Estadísticas de largo plazo". Caracterización: Estadísticas de largo plazo (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ "CORDOBA OBS Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ "87345: Cordoba Observatorio (Argentina)". ogimet.com. OGIMET. 7 November 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ "87345: Cordoba Observatorio (Argentina)". ogimet.com. OGIMET. 3 February 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ "Station Cordoba" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ "87344: Cordoba Aerodrome (Argentina)". ogimet.com. OGIMET. 7 November 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ "87344: Cordoba Aerodrome (Argentina)". ogimet.com. OGIMET. 3 February 2024. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ Velázquez, Guillermo Angel; Lende, Sebastián Gómez (2004). "Dinámica migratoria: coyuntura y estructura en la Argentina de fines del XX". Amérique Latine Histoire et Mémoire (9). Alhim.revues.org. doi:10.4000/alhim.432. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Buenosaires.gov.ar". Archived from the original on 29 September 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- ^ "Censo 2008: Somos menos que lo que se esperaba" (in Spanish). La Voz del Interior. Archived from the original on 30 December 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- ^ "Observatorio urbano – Guías estadísticas: Capítulo III: Demografía" (PDF) (in Spanish). Municipalidad de Córdoba. 2007. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ^ "Censo 2010" (in Spanish). La Voz del Interior. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ^ "Datos territoriales de Córdoba" (in Spanish). 2007. Archived from the original on 25 September 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ "Circunvalación completa: rodear la ciudad de Córdoba demanda 34 minutos" (in Spanish). LaVoz. 6 July 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ Córdoba - Villa María on Satélite Ferroviario

- ^ Horarios Buenos Aires-Córdoba, Trenes Argentinos website Archived 26 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 15 June 2015

- ^ Retiro Córdoba on Satélite Ferrovario

- ^ "15 trenes turísticos de la Argentina", Clarín, 25 May 2015

- ^ "Puesta en marcha del tren rápido Rosario-Buenos Aires-Córdoba" Archived 12 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine, La Capital, 8 May 2006

- ^ "Randazzo sepulta el proyecto de tren bala a Córdoba", La Voz, 20 December 2012

- ^ "Empresa que iba a construir tren bala argentino reconoció pago de coimas", La Noticia 1, 13 December 2014

- ^ "Córdoba Public Transportation Statistics". Global Public Transit Index by Moovit. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - ^ "The CNH Industrial Site in Córdoba, Argentina, Achieves Bronze Level Designation in World Class Manufacturing". London: CNH Industrial. 7 December 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ 1990 World Championship for Men, Archive.FIBA.com, Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ Montero, Sergio; Chapple, Karen (2018). Fragile Governance and Local Economic Development: Theory and Evidence from Peripheral Regions in Latin America. Routledge. p. 131. ISBN 9781351589437.

- ^ "Deutscher Bundestag 4. Wahlperiode Drucksache IV/3672" (Archive). Bundestag (West Germany). 23 June 1965. Retrieved 12 March 2016. p. 18/51.

- ^ "Osvaldo Ardiles: The Playmaker That Shaped English Football". 14 September 2021.

- ^ "Osvaldo Ardiles | Actor, Writer, Soundtrack". IMDb.

External links

[edit]- Municipality of Córdoba official website

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. VI (9th ed.). 1878. p. 390.

- Municipal information: Municipal Affairs Federal Institute (IFAM), Municipal Affairs Secretariat, Ministry of Interior, Argentina. (in Spanish)