Clomazone

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

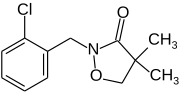

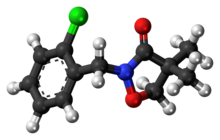

| Preferred IUPAC name 2-[(2-Chlorophenyl)methyl]-4,4-dimethyl-1,2-oxazolidin-3-one | |

| Other names Dimethazone | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.125.682 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID | |

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C12H14ClNO2 | |

| Molar mass | 239.69806 |

| Appearance | white solid |

| Melting point | 33.9 °C (93.0 °F; 307.0 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

Clomazone is an agricultural herbicide, and has been the active ingredient of products named "Command" and "Commence". The molecule consists of a 2-chlorobenzyl group bound to a N-O heterocycle called isoxazolidinone. It is a white solid.

Clomazone was first registered by the USEPA on March 8, 1993, and was commercialized by FMC Corporation. It is used for broadleaf weed control in several crops, including soybeans, peas, maize, oilseed rape, sugar cane, cassava, pumpkins and tobacco.[1] It may be applied pre-emergence of incorporated before planting the crop. Clomazone is relatively volatile (vapor pressure is 19.2 mPa) and vapors induce striking visual symptoms on non-target sensitive plants. Clomazone undergoes biological degradation, exhibiting a soil half life of one to four months.[2] Adsorption of the herbicide to soil solids slows degradation and volatilization.[3] Encapsulation helps reduce volatility and therefore reduces off-target damage to sensitive plants.[4]

Clomazone suppresses the biosynthesis of chlorophyll and other plant pigments.[5][6]

References

[edit]- ^ Tomlin, CD. 1997. The pesticide manual, 11th edition. British Crop Protection Council. Farnham, Surrey, UK. p 256-257. ISBN 978-1901396881.

- ^ Mervosh, T. L., G.K. Sims, and E.W. Stoller. 1995. Clomazone fate in soil as affected by microbial activity, temperature, and soil moisture. J. Agric. Food Chem. 43:537-543. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf00050a052.

- ^ Mervosh, T. L., G.K. Sims, E.W. Stoller, and T.R. Ellsworth. 1995. Clomazone sorption in soil: Incubation time, temperature, and soil moisture effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 43:2295-2300. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf00056a062.

- ^ Mervosh, T. L., E.W. Stoller, T.R. Ellsworth, and G.K. Sims. 1995. Effects of starch encapsulation on clomazone and atrazine movement in soil and clomazone volatilization. Weed Science. 43:445-453. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043174500081455.

- ^ Storzer, Werner "The residue behaviour of new herbicides in crop plants" Nachrichtenblatt des Deutschen Pflanzenschutzdienstes 2002, vol. 54, 193-203.

- ^ Gara, Pedro M. David; Rosso, Janina A.; Martin, Marcela V.; Bosio, Gabriela N.; Gonzalez, Monica C.; Martire, Daniel O. "Characterization of humic substances and their role in photochemical processes of environmental interest" Trends in Photochemistry & Photobiology 2011, vol. 13, pages 51-70.