Djadjawurrung

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2,500[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Djadjawurrung, English | |

| Religion | |

| Australian Aboriginal mythology, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Bunurong, Taungurung, Wathaurong, Wurundjeri see List of Indigenous Australian group names |

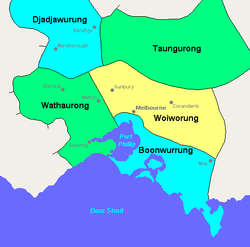

Dja Dja Wurrung (Pronounced Ja-Ja-war-rung), also known as the Djaara or Jajowrong people and Loddon River tribe, are an Aboriginal Australian people who are the traditional owners of lands including the water catchment areas of the Loddon and Avoca rivers in the Bendigo region of central Victoria, Australia.[2] They are part of the Kulin alliance of Aboriginal Victorian peoples.[1] There are 16 clans, which adhere to a patrilineal system. Like other Kulin peoples, there are two moieties: Bunjil the eagle and Waa the crow.[3]

Name

[edit]The Dja Dja Wurrung ethnonym is often analysed as a combination of a word for "yes" (djadja, dialect variants such as yeye /yaya, are perhaps related to this) and "mouth" (wurrung). This is quite unusual, since many other languages of the region define their speakers in terms of the local word for "no".[4] It had, broadly speaking, two main dialects, an eastern and western variety.[5]

Language

[edit]Dja Dja Wurrung is classified as one of the Kulin languages. Some 700 words were taken down by Joseph Parker in 1878, while R. H. Mathews produced an outline of its grammar, published in German in 1904.[6]

Country

[edit]According to Norman Tindale and Ian D. Clark, Their lands once extended over 16,000 square kilometres (6,200 sq mi), embracing the Upper Loddon and Avoca rivers, running east, through Maldon and Bendigo to around Castlemaine and west as far as St. Arnaud. It takes in the area close to Lake Buloke. The northern reaches touch Boort and, northwest, Donald, while Creswick, Daylesford and Woodend marks its southern frontier, and to the southwest, Navarre Hill and Mount Avoca. Stuart Mill, Natte Yallock and Emu and the eastern headwaters of the Wimmera River all lie within Dja Dja Wurrung traditional land.[7][8]

History

[edit]The Dja Dja Wurrung are bound to their land by their spiritual belief system deriving from the Dreaming, when mythic beings had created the world, the people and their culture. They were part of established trade networks which allowed goods and information to flow over substantial distances. The Tachylite deposits near Spring Hill and the Coliban River may have been important trade goods as stone artefacts from this material have been found around Victoria.[9]

There is evidence that smallpox, perhaps introduced first from the north by Macassan traders, swept through the Djadja Wurrung in 1789 and 1825. According to a census undertaken in 1840, there were 282 Djadja wurrung, all that remained of the 900–1900 people estimated to be in Djadja wurrung territory in 1836 when the first white colonizer, Thomas Mitchell, passed through their territory.[10] Mitchell reported finding large fertile plains. The settlement of the Goulburn and Loddon Districts began the following year by squatters eager to carve out a station and run.[11] As to the epidemics, they were incorporated into Aboriginal mythology as a giant snake, the Mindye, sent by Bunjil, to blow magic dust over people to punish them for being bad.[12]

Munangabum

[edit]Munangabum was an influential clan head of the Liarga balug and spiritual Leader or neyerneyemeet of the Djadja wurrung who lived through two smallpox epidemics and shaped his people's response to European settlement in the 1830s and 1840s. On 7 February 1841, Munangabum was shot and wounded by settlers while his companion Gondiurmin died at Far Creek Station, west of Maryborough. Three settlers were later apprehended and tried on 18 May 1841 but were acquitted for want of evidence as aborigines could not give evidence in courts of law.[13] He was murdered in 1846 by a rival clan-head from the south.[14]

Massacres

[edit]The European settlement of Western Victoria in the 1830s and 1840s was marked by resistance to the invasion, often by the driving off of sheep, which then resulted in conflict and sometimes a massacre of aboriginal people. The Dja Dja Wurrung peoples experienced two waves of settlement and dispossession: from the south from 1837 and from the north from 1845.[3]

Very few of these reports were acted upon to bring the settlers to court. On the few occasions when this did happen, the cases were dismissed as aborigines were denied the right to give evidence in courts of law. Neil Black, a squatter in Western Victoria writing on 9 December 1839, states the prevailing attitude of many settlers:

The best way (to procure a run) is to go outside and take up a new run, provided the conscience of the party is sufficiently seared to enable him without remorse to slaughter natives right and left. It is universally and distinctly understood that the chances are very small indeed of a person taking up a new run being able to maintain possession of his place and property without having recourse to such means – sometimes by wholesale...[15]

Table: reported killings in Dja Dja Wurrung territory to 1859[16]

| Date | Location | Aborigines involved | Europeans involved | Aboriginal deaths reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| March–April 1838 | Unknown | Dja Dja Wurrung, clan unknown | two Europeans | Koonikoondeet and another man |

| Winter 1838 | Darlington Station, about 16 km from Lancefield | Dja Dja Wurrung or Taungurung | Captain Sylvester Brown's employees | 13 people |

| June 1838 | Waterloo Plains massacre | unknown | employees of WH Yaldwyn, CH Ebden, H Munro, and Dr W Bowman | 7 or 8-but probably many more people |

| February 1839 | Maiden Hills | Dja Dja Wurrung, clan unknown | John Davis and Abraham Braybrook, convict shepherds, and William Allan | Noorowurnin and another person |

| May 1839[17] | Campaspe Plains, see the Campaspe Plains massacre for detail | Taungurung, clan unknown | Charles Hutton and party of settlers | About 40 killed |

| June 1839 | Campaspe Plains, known as the Campaspe Plains massacre | Dja Dja Wurrung, clan unknown | Charles Hutton and party of mounted police | At least 6 people killed, many wounded |

| late 1839 or early 1840 | Middle Creek, known as the Blood Hole | Dja Dja Wurrung, clan unknown | Captain Dugald McLachlan and his employees | Unknown |

| August 1840 | unknown | Dja Dja Wurrung, clan unknown | one of Henry Dutton's assigned servants | Pandarragoondeet |

| 7 February 1841 | 14 Mile Creek, Glenmona Station west of Maryborough | Dja Dja Wurrung, Galgal gundidj clan | William Jenkins, William Martin, John Remington, Edward Collin, Robert Morrison | Gondiurmin, Munangabum wounded |

| 15 May 1844 | 100 km north of Pyrenee range | presumably Dja Dja Wurrung | Native Police Corps in the charge of Crown Commissioner FA Powlett and HEP Dana | Leelgoner |

| 28 June 1846 | Avoca River near Charlton | Dja Dja Wurrung, clan unknown | John Fox | one person |

Rape and frontier sexual interaction

[edit]An important source of frontier conflict was sexual relations between European settlers and aboriginal women. Historian Bain Attwood claims that aboriginal clans may have sought to incorporate whites into their kinship society through sexual relations with its principles and obligations of reciprocity and sharing; however, this would have been misconstrued by the settlers as prostitution, resulting in cultural misunderstanding and conflict. Abduction and rape of aboriginal women was also relatively common, often leading to violent interactions. While most squatters ignored such sexual interactions by their employees and even participated, there were a few, such as John Stuart Hepburn, who discouraged sexual interactions between his employees and the Dja Dja Wurrung.[18]

Edward Parker commented:

Were the settlers generally to follow the example of Mr Hepburn, much of the liberal intercourse between the labouring men and native women, and consequently the endangering of property, would be suppressed.[18]

Parker expressed in 1842 the "firm conviction... that nine out of ten outrages committed by the blacks" derived either directly or indirectly from sexual relations. While he considered the "labouring classes" the worst offenders, he also indicated there were "individuals claiming the rank of gentleman and even aspiring to be administrators of the law" who abused Aboriginal women.[18]

The widespread abuse of aboriginal women led directly to an epidemic of venereal disease, syphilis and gonorrhea, which had a major impact on reducing the fertility of Dja Dja Wurrung women and increased the mortality rate of infants.[19]

Loddon Aboriginal Protectorate Station at Franklinford

[edit]

Edward Stone Parker was appointed in England by the Colonial Office as an Assistant Protector of Aborigines in the Aboriginal Protectorate established in the Port Philip district under George Robinson. He arrived in Melbourne in January 1839 with Robinson appointing Parker to the northwest or Loddon District in March. He did not start his protectorate until September 1839. The Protector's duties included to safeguard aborigines from "encroachments on their property, and from acts of cruelty, of oppression or injustice" and a longer term goal of "civilising" the natives.[20]

Parker initially established his base at Jackson's Creek near Sunbury, which was not close enough to the aboriginal nations of his protectorate. Parker suggested to Robinson and to Governor Gipps that protectorate stations be established within each district to concentrate aboriginals in one area and provide for their needs and so reduce frontier conflict. The Governor of NSW, Sir George Gipps, agreed and stations or reserves for each protector were approved in 1840. Parker's original choice for a reserve in September 1840 was a site, known as Neereman by the Dja Dja Wurrung, on Bet Bet Creek a tributary of the Loddon River. However, the site proved unsuitable for agriculture and in January 1841 Parker selected a site on the northern side of Mount Franklin on Jim Crow Creek with permanent spring water. The site was chosen with the support of The Dja Dja Wurrung as well as Crown Lands Commissioner Frederick Powlett. Approval for the site was given in March, and a large number of Dja Dja Wurrung accompanied Parker there in June 1841 when the station was established on William Mollison's Coliban run, where an outstation hut already existed.[21] This became known as the Loddon Aboriginal Protectorate Station at Franklinford, and the area was known to the Dja Dja Wurrung as Larne-ne-barramul or the habitat of the emu. Nearby Mount Franklin was known as Lalgambook.[22]

Franklinford provided a very important focus for the Dja Dja Wurrung during the 1840s where they received a measure of protection and rations, but they continued with their traditional cultural practices and semi-nomadic lifestyle as much as they could. Parker employed a medical officer, Dr W. Baylie, to treat the high incidence of disease.[20]

Parker also attempted to prosecute those European settlers who had killed aborigines including Henry Monro and his employees for killings in January 1840 and William Jenkins, William Martin, John Remington, Edward Collins, Robert Morrison for the murder of Gondiurmin in February 1841. Both cases were thrown out of court due to the inadmissibility of aboriginal witness statements and evidence in Courts of Law. Aboriginals were regarded as heathens, unable to swear on the bible, and therefore unable to give evidence. This made prosecution of settlers for crimes against aborigines exceedingly difficult, while also making it very difficult for aborigines to offer legal defences when they were prosecuted for such crimes as sheep stealing.[20]

The colonial Government severely curtailed funding to the protectorate from 1843. The protectorate ended on 31 December 1848, with about 20 or 30 Dja Dja Wurrung living at the station at that time. Parker and his family remained living at Franklinford. Six Dja Dja Wurrung men and their families settled at Franklinford, but all but one died from misadventure or respiratory disease. Tommy Farmer (Beernbarmin)[23] was the last survivor of this group who walked off the land in 1864 and eventually joined the Coranderrk reserve.[24] [citation needed] One Dja Dja Wurrung woman known as Ellen, under Parker's protection, crotcheted a collar, and wrote two congratulatory letters, as a gift the occasion of the marriage of the Prince of Wales, Edward VII to Princess Alexandra of Denmark in 1863. Queen Victoria responded with a thank you note.[25]

Impact of disease

[edit]While frontier conflict, murder and massacre took their toll, the impact of disease had a far greater impact. Epidemics of smallpox had already decimated the tribe even before first contact with Europeans. From the late 1830s European contact introduced consumption, venereal disease, the common cold, bronchitis, influenza, chicken pox, measles and scarlet fever. Venereal diseases of syphilis and gonorrhea reached epidemic proportions with estimates of 90% of Dja Dja Wurrung women thought to be suffering from syphilis by late 1841. This also had the effect of rendering aboriginal women infertile, and infecting any infants born causing high infant mortality and a plummeting birthrate. A Medical doctor appointed for a time confirmed the prevalence of venereal disease.[19]

Those most dramatically affected were the groups who had most contact with European settlers. Spending longer times in the same camping places also made them susceptible to respiratory diseases and gastric illnesses. When several Dja Dja Wurrung died on the reserve at Franklinford in 1841, many of them temporarily abandoned the place. A number of deaths and illnesses among the whites working at Franklinford in 1847–48 also caused many Dja Dja Wurrung to leave on the belief that the ground at Franklinford was "malignant". By December 1852 the population of Dja Dja Wurrung was estimated at 142 people, whereas they had numbered between one and two thousand just 15 years previously at time of first contact.[19]

Victorian gold rush

[edit]The onset of the Victorian Gold Rush in 1851 placed further pressure on the Dja Dja Wurrung with 10,000 diggers occupying Barkers Creek, Mount Alexander and many streams turned into alluvial gold diggings with many sacred sites violated. The gold rush also caused a crisis in agricultural labour, so many of the squatters employed Dja Dja Wurrung people as shepherds, stockriders, station hands and domestic servants on a seasonal or semi-permanent basis. Many of those that could not find work with the squatters survived on the margins of white society through begging and prostitution for food, clothes and alcohol. The availability of alcohol increased with the number of bush inns and grog shanties associated with the diggings, and drunkenness became a serious problem. Mortality rates worsened during the gold rushes.[26]

Anecdotal accounts reveal that many Dja Dja Wurrung chose to move north away from the diggings to avoid the problems of alcoholism, prostitution and begging associated with living on the margin of white society.[26]

A small number of Dja Dja Wurrung remained at Franklinford with Parker, farming the land, erecting dwellings and selling their produce to the nearest diggings about 2 miles away.

The Jaara baby

[edit]The Jaara baby was an Aboriginal Australian child who died at some stage during the 1840s to 1860s. The child's remains were discovered, together with child's toys consisting of feathers, a waist belt and European artefacts, in the fork of a tree in 1904, and kept in storage by Museum Victoria for ninety-nine years, until in 2003 they were repatriated to the Dja Dja Wurrung community.[27]

Resettlement

[edit]An investigation into the conditions at Franklinford in February 1864 by Coranderrk superintendent John Green and Guardian of the Aborigines William Thomas found the protectorate school unfit for instruction and that the farms had all been abandoned. Green recommended closure of the school and removal of the children to Coranderrk, with Thomas agreeing to the move but opposing the breaking up of the Protectorate Station. Thomas was supported by Parker in this.[26]

Dja Dja Wurrung people at Franklinford were forced to re-settle at Coranderrk station on the land of the Wurundjeri. There were 31 adults and 7 children reported belonging to the Dja Dja Wurrung at this time.[28]

Thomas Dunolly, a Dja Dja Wurrung child when he was forcibly resettled at Coranderrk Reserve, went on to play an important part in the first organised protest by aborigines to save Coranderrk in the 1880s. Caleb and Anna Morgan, descendants of Caroline Malcolm who resettled at Coranderrk, were active members of the Australian Aborigines League founded by William Cooper in 1933–34.[26]

On 26 May 2004 Aunty Susan Rankin, a Dja Dja Wurrung elder peacefully reoccupied crown land at Franklinford in central Victoria, calling her campsite the Going Home Camp. Rankin asked the Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment to produce documents proving that the Crown has the right to occupy these lands. According to the 2 June 2004 Daylesford Advocate, local DSE officers admitted they "cannot produce these documents and doubt that such documents exist".[29]

Structure, borders and land use

[edit]

Communities consisted of 16 land-owning groups called clans that spoke a related language and were connected through cultural and mutual interests, totems, trading initiatives and marriage ties. Access to land and resources by other clans, was sometimes restricted depending on the state of the resource in question. For example; if a river or creek had been fished regularly throughout the fishing season and fish supplies were down, fishing was limited or stopped entirely by the clan who owned that resource until fish were given a chance to recover. During this time other resources were utilised for food. This ensured the sustained use of the resources available to them. As with most other Kulin territories, penalties such as spearings were enforced upon trespassers. Today, traditional clan locations, language groups and borders are no longer in use and descendants of Dja Dja Wurrung people live within modern day society, although still preserving much of their culture.

Clans

[edit]Before European settlement, 16 separate clans existed, each with a clan headman.[30]

| No | Clan name | Approximate location |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bial balug | Bealiba |

| 2 | Burung balug | Natte Yallock |

| 3 | Bulangurd gundidj | Mount Bolangum |

| 4 | Cattos run clan | Bridgewater |

| 5 | Galgal balug | Burnbank and Mount Mitchell |

| 6 | Djadja wurrung balug | unknown |

| 7 | Galgal gundidj | northwest of Kyneton |

| 8 | Gunangara gundidj | Larrnebarramul, near Mount Franklin |

| 9 | Larnin gundidj | Richardson River |

| 10 | Liarga balug | Mount Tarrengower and Maldon |

| 11 | Munal gundidj | Daylesford |

| 12 | Dirag balug | Avoca |

| 13 | Durid balug | Mount Moorokyle and Smeaton |

| 14 | Wurn balug | between Carisbrook and Daisy Hill |

| 15 | Wungaragira gundidj | upper Avoca River and near St Arnaud |

| 16 | Yung balug | Mount Buckrabanyule |

Diplomacy

[edit]When foreign people passed through or were invited onto Dja Dja Wurrung lands, the ceremony of Tanderrum – freedom of the bush – would be performed. This allowed safe passage and temporary access and use of land and resources by foreign people. It was a diplomatic rite involving the landholder's hospitality and a ritual exchange of gifts.

Recognition and settlement agreement with the State of Victoria

[edit]On 28 March 2013, the State of Victoria and the Dja Dja Wurrung people entered into a Recognition and Settlement Agreement under the Victorian government's Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010, which formally recognises the Dja Dja Wurrung people as the traditional owners for part of Central Victoria. The agreement area extends from north of the Great Dividing Range near Daylesford and includes part or all of the catchments of the Richardson, Avon, Avoca, Loddon and Campaspe Rivers. It includes, inter alia, Crown land in the City of Greater Bendigo, Lake Boort and part of Lake Buloke.[31] The agreement was the culmination of eighteen months of negotiations between the Victorian Government and the Dja Dja Wurrung people and settles native title claims dating back to 1998.[31]

At the ceremony, Victorian Attorney-General, Robert Clark said: "The Victorian Government is pleased to have reached this settlement in a way that has avoided costly litigation, while assisting the Traditional Owner community to develop a sustainable future."[32]

A ceremony to mark the settlement agreement was held in Bendigo on 15 November 2013, following the registration of the Indigenous land use agreement being the final step to formalise the agreement.[33]

Alternative names and spelling

[edit]- Djadjawurrung

- Djadjawuru, Djadjawurung, Djendjuwuru

- Jarrung Jarrung, Ja-jow-er-ong

- Jurobaluk

- Lewurru (language name, composed of Ie (no) and wur:u (lip/ speech).

- Lunyingbirrwurrkgooditch

- Monulgundeech (lit. "men of the dust"), Monulgundeedh.

- Pilawin (horde in the Pyrenees)

- Tarrang, Tarra

- Tjedjuwuru, Tyeddyuwurru

- Yabola

- Yang (the Djadjawurrung toponym for Avoca)

- Yarrayowurro

- Yaura

- Yayaurung, Jajaorong (from jajae (= jeje, "yes"), Jajaurung, Jajowurrong, Jajowurong, Jajowrong, Jarjoworong, Jajowerang, Jajowrung, Jajow(e)rong, Jajoworrong.

Source: Tindale 1974

Some words

[edit]- pumpum (egg)

- pupup (baby)[34]

- tjaka, tjakila (western dialect): tjakala (eastern dialect) means "to eat"[35]

- weka (to laugh)[36]

Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Australian Associated Press 2004.

- ^ "Djaara (Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation)". Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ a b Clark 1995, p. 85.

- ^ Blake 2011, p. 11.

- ^ Blake 2011, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Blake 2011, p. 8.

- ^ Tindale 1974.

- ^ Clark 1995, p. 86.

- ^ Clark & Howes 2010.

- ^ Lester & Dussart 2014, p. 146.

- ^ Attwood 1999, p. 5.

- ^ Attwood 1999, pp. 4ff.

- ^ Clark 1995, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Lester 2014, p. 61.

- ^ Clark 1995, p. 1.

- ^ Clark 1995, pp. 88–101.

- ^ Attwood 1999, pp. 7–9.

- ^ a b c Attwood 1999, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c Attwood 1999, pp. 34–36.

- ^ a b c Attwood 1999, pp. 23–28.

- ^ Attwood 1999, pp. 26f.

- ^ Morrison 1967.

- ^ Lester & Dussart 2014, p. 163.

- ^ Broome 2005, p. 115.

- ^ Blake 2011, p. 11 note 4.

- ^ a b c d Attwood 1999, pp. 37–45.

- ^ Taylor 2003.

- ^ Clark 1995, p. 88.

- ^ Murphy 2004.

- ^ Clark 1995, p. 87.

- ^ a b Settlement 2013.

- ^ Bendigo Advertiser 2013.

- ^ Reed 2013.

- ^ Blake 2011, p. 61.

- ^ Blake 2011, p. 54.

- ^ Blake 2011, p. 55.

Sources

[edit]- "Aboriginals ready to fight for artefacts". The Sydney Morning Herald. Australian Associated Press. 27 July 2004. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

- Attwood, Bain (1999). "My Country": A History of the Djadja Wurrung, 1837–1864. Department of History, Monash University. ISBN 978-0-732-61766-0.

- Blake, Barry J. (2011). Dialects of Western Kulin, Western Victoria Yartwatjali, Tjapwurrung, Djadjawurrung (PDF). La Trobe University.

- Broome, Richard (2005). Aboriginal Victorians: A History Since 1800. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74114-569-4.

- Clark, Ian D. (1995). Scars in the Landscape: a register of massacre sites in western Victoria, 1803–1859 (PDF). AIATSIS. pp. 169–175. ISBN 0-85575-281-5.

- Clark, V; Howes, J (2010). Calder Freeway Faraday to Ravenswood, Harcourt North Section: Archaeological Monitoring During Construction. VicRoads.

- "Dja Dja Wurrung native title claim settled". Bendigo Advertiser. 28 March 2013.

- "Dja Dja Wurrung settlement". State Government of Victoria. 24 October 2013.

- Lester, Alan (2014). "Indigenous Engagements with Humanitarian Governance: The Port Phillip Protectorate of Aborigines and "Humanitarian Space"". In Carey, Jane; Lydon, Jane (eds.). Indigenous Networks: Mobility, Connections and Exchange. Routledge. pp. 50–74. ISBN 978-1-317-65932-7.

- Lester, Alan; Dussart, Fae (2014). Colonization and the Origins of Humanitarian Governance: Protecting Aborigines across the Nineteenth-Century British Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00783-3.

- Morrison, Edgar (1967) [First published 1854]. Frontier life in the Loddon Protectorate: episodes from early days, 1837-1842.

{{cite book}}:|newspaper=ignored (help) - Murphy, Margaret (7 July 2004). "Sovereignty, not sorry". Green Left Weekly.

- Reed, Merran (15 November 2013). "Indigenous people rejoice in emotional ceremony". Bendigo Advertiser.

- Taylor, Josie (September 2003). "Indigenous people rejoice in emotional ceremony". ABC News.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Jaara (VIC)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.

External links

[edit]- The Loddon Aboriginals - A brief history researched and written by Norm Darwin, 1999.

- Australian Aboriginal Online Maps – A collection of community contributed & researched locations, plants, sites.

- Bibliography of Djadja Wurrung people and language resources, at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies