Golden Haggadah

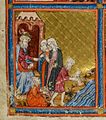

The Golden Haggadah is a Hebrew illuminated manuscript originating around c. 1320–1330 in Catalonia. It is an example of an Illustrated Haggadah, a religious text for Jewish Passover. It contains many lavish illustrations in the High Gothic style with Italianate influence, and is perhaps one of the most distinguished illustrated manuscripts created in Spain. The Golden Haggadah is now in the British Library and can be fully viewed as part of their Digitized Manuscript Collection MS 27210.[1]

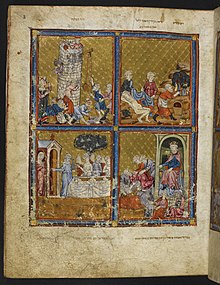

The Golden Haggadah measures 24.7×19.5 cm, is made of vellum, and consists of 101 leaves. It is a Hebrew text written in square Sephardi script. There are fourteen full-page miniatures, each consisting of four scenes on a gold ground. It has a seventeenth-century Italian binding of dark brown sheepskin. The manuscript has outer decorations of blind-tooled fan-shaped motifs pressed into the leather cover with a heated brass tool on the front and back.[2]

The Golden Haggadah is a selection of texts to be read on the first night of Passover, dealing with the Exodus of the Israelites. It is composed of three main parts. These are fourteen full pages of miniatures, a decorated Haggadah text, and a selection of 100 Passover piyyutim liturgical poems.[3]

The first section of miniatures portray the events of the Biblical books of Genesis and Exodus, ranging from Adam naming the animals and concluding with the song of Miriam.[4] The following set of illustrations consist of illustrated steps on the preparations needed for Passover. The second section of the decorated Haggadah text contains text decorated with initial word panels. These also included three text illustrations showing a dragon drinking wine (fol.27), the mazzah (fol.44v), and the maror (fol.45v). The concluding section of the piyyutim consists of only initial-word panels.[2]

History

[edit]The Golden Haggadah is presumed to have been created sometime around 1320–1330. While originating in Spain, it is believed that the manuscript found its way to Italy in possession of Jews banished from the country in 1492.[2]

The original illustrators for the manuscript are unknown. Based on artistic evidence, the standing theory is that there were at least two illustrators.[2] While there is no evidence of different workshops producing the manuscript, there are two distinct artistic styles used respectively in groupings of eight folios on single sides of the pages. The first noticeable style is an artist who created somewhat standardized faces for their figures, but was graceful in their work and balanced with their color. The second style seen was very coarse and energetic in comparison.[2]

The original patron who commissioned the manuscript is unknown. The prevailing theory is that the first known owner was Rabbi Joav Gallico of Asti, who presented it as a gift to his daughter Rosa's bridegroom, Eliah Ravà, on the occasion of their wedding in 1602. The evidence for this theory is the addition to the manuscript of a title page with an inscription and another page containing the Gallico family coat of arms in recognition of the ceremony.[2][5] The commemorative text inscribed in the title page translates from the Hebrew as:

“NTNV as a gift [...] the honored Mistress Rosa,

(May she be blessed among the women of the tent), daughter of our illustrious

Honored Teacher Rabbi Yoav

Gallico, (may his Rock preserve him) to his son-in-law, the learned

Honored Teacher Elia (may his Rock preserve him)

Son of the safe, our Honored Teacher, the Rabbi R. Menahem Ravà (May he live Many good years)

On the day of his wedding and the day of the rejoicing of his heart,

Here at Carpi, the tenth of the month of Heshvan, Heh Shin Samekh Gimel (1602)”[5]

The translation of this inscription has led to debate on who originally gave the manuscript, either the bride Rosa or her father Rabbi Joav. This confusion originates with translation difficulties of the first word and a noticeable gap that follows it, leaving out the word “to” or “by”. There are three theorized ways to read this translation.

The current theory is a translation of “He gave it [Netano] as a gift. . .[ignores references to Mistress Rosa]. . .to his son-in-law. . .Elia.” This translation works to ignore the reference to the bride and states that Rabbi Joav presented the manuscript to his new son-in-law. This presents the problem of why the bride would be mentioned after the use of the verb “he gave” and leaving out the follow-up of “to” seen as prefix “le”. In support of this theory is that the prefix “le” is used in the second half of the inscription pointing to the groom Elia being the receiver, thus making this the prevailing theory.[5]

Another translation is “They gave it [Natnu] as a gift. . .Mistress Rosa (and her father?) to. . . his (her father’s) son-in-law Elia.” This supports the theory that the manuscript was given by both Rosa and Rabbi Joav together. The problem with this reading is the strange wording used to describe Rabbi Joav's relationship to Elia and his grammatical placement after Rosa's name as an afterthought.[5]

The most grammatically correct translation is “It was given [Netano (or possibly Netanto)] as a gift [by]. . .Mistress Rosa to. . .(her father’s) son-in-law Elia.”. This suggests that the manuscript was originally Rosa's and she gifted it to her groom, Elia. This theory also has its flaws in that this would mean the male version of “to give” was used for Rosa and not the feminine version. In addition, Elia is referred to as the son-in-law of her father, rather than merely her groom, which makes little sense if Rabbi Joav was not involved in some form.[5]

Additional changes to the manuscript that can be dated include a mnemonic poem of the laws and customs of Passover on blank pages between miniatures added in the seventeenth century, a birth entry of a son in Italy 1689, and the signatures of censors for the years 1599, 1613, and 1629.[2]

The Golden Haggadah is now in the London British Library shelf mark MS 27210.[6][7] It was acquired by the British Museum in 1865 as part of the collection of Joseph Almanzi of Padua.[2]

Illuminations

[edit]

The miniatures of the Golden Haggadah all follow a similar layout. They are painted onto the flesh side of the vellum and divided into panels of four frames read in the same direction as the Hebrew language, from right to left and from top to bottom. The panels each consist of a background in burnished gold with a diamond pattern stamped onto it. A border is laid around each panel made of red or blue lines, the inside of which are decorated with arabesque patterns. This can be seen in the Dance of Marian where blue lines frame the illustration with red edges and white arabesque decorating inside them. At the edge of each collection of panels can also be found black floral arabesque growing out from the corners.[3]

The miniatures of the Golden Haggadah are decidedly High Gothic in style. This was influenced by the early 14th-century Catalan School, a Gothic style that is French with Italianate influence. It is believed that the two illustrators who worked on the manuscript were influenced by and studied other similar mid-13th-century manuscripts for inspiration, including the famous Morgan Crusader Bible and the Psalter of Saint Louis. This could be seen in the composition of the miniatures' French Gothic styling. The architectural arrangements, however, are in Italianate form as evidenced by the coffered ceilings created in the miniatures. Most likely these influences reached Barcelona in the early 14th century.[2][3]

Purpose

[edit]The Haggadah is a copy of the liturgy used during the Seder service of Jewish Passover. The most common traits of a Haggadah are the inclusion of an introduction on how to set the table for a seder, an opening mnemonic device for remembering the order of the service, and content based on the Hallel Psalms and three Pedagogic Principles. These written passages are intended to be read aloud at the beginning of Passover and during the family meal. These holy manuscripts were generally collected in private handheld devotional books.[8]

The introduction of Haggadah as illustrated manuscripts occurred around the 13th and 14th centuries. Noble Jewish patrons of the European royal courts would often use the illustration styles of the time to have their Haggadah made into illustrated manuscripts. The manuscripts would have figurative representations of stories and steps to take during service combined with traditional ornamental workings of the highest quality at the time. In regards to the Golden Haggadah, it was most likely created as a part of this trend in the early 14th century. It is considered one of the earliest examples of illustrated Haggadot of Spanish origin to contain a complete sequence of illustrations of the books of Genesis and Exodus.[9] The Sarajevo Haggadah of about 1350 is probably the next best known example from Catalonia.

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Golden Haggadah". The British Library. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Narkiss, Bezalel (1969). Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts. Jerusalem, Encyclopaedia Judaica; New York Macmillan. p. 56. ISBN 0814805930.

- ^ a b c Walther, Ingo (2001). Codices illustres: the world's most famous illuminated manuscripts 400-1600. Köln; London; New York : Taschen. p. 204. ISBN 3822858528.

- ^ Mann, Vivian B. (2019-12-31), "The Unknown Jewish Artists of Medieval Iberia", The Jew in Medieval Iberia, 1100-1500, Academic Studies Press, pp. 138–179, doi:10.1515/9781618110541-007, ISBN 978-1-61811-054-1, retrieved 2024-09-14

- ^ a b c d e Epstein, Marc (2011). The Medieval Haggadah: Art, Narrative, and Religious Imagination. New Haven : Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300158946.

- ^ Walther, Ingo (2001). Codices illustres: the world's most famous illuminated manuscripts 400-1600. Köln; London; New York : Taschen. p. 204. ISBN 3822858528.

- ^ "Collection Items-Golden Haggadah bl.uk". British Library.

- ^ Millgram, Abraham (1971). Jewish Worship. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America. ISBN 0827600038.

- ^ Walther, Ingo (2001). Codices illustres: the world's most famous illuminated manuscripts 400-1600. Köln; London; New York : Taschen. p. 204. ISBN 3822858528.

Additional References

[edit]- Bezalel Narkiss, The Golden Haggadah (London: British Library, 1997) [partial facsimile].

- Marc Michael Epstein, Dreams of Subversion in Medieval Jewish Art and Literature (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997), pp. 16–17.

- Katrin Kogman-Appel, 'The Sephardic Picture Cycles and the Rabbinic Tradition: Continuity and Innovation in Jewish Iconography', Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 60 (1997), 451–82.

- Katrin Kogman-Appel, 'Coping with Christian Pictorial Sources: What Did Jewish Miniaturists Not Paint?' Speculum, 75 (2000), 816–58.

- Julie Harris, 'Polemical Images in the Golden Haggadah (British Library Add. MS 27210)', Medieval Encounters, 8 (2002), 105–22.

- Katrin Kogman-Appel, Jewish Book Art Between Islam and Christianity: the Decoration of Hebrew Bibles in Medieval Spain (Leiden: Brill, 2004), pp. 179–85.

- Sarit Shalev-Eyni, 'Jerusalem and the Temple in Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts: Jewish Thought and Christian Influence', in L'interculturalita dell'ebraismo a cura di Mauro Perani (Ravenna: Longo, 2004), pp. 173–91.

- Julie A. Harris, 'Good Jews, Bad Jews, and No Jews at All: Ritual Imagery and Social Standards in the Catalan Haggadot', in Church, State, Vellum, and Stone: Essays on Medieval Spain in Honor of John Williams, ed. by Therese Martin and Julie A. Harris, The Medieval and Early Modern Iberian World, 26 (Leiden: Brill, 2005), pp. 275–96 (p. 279, fig. 6).

- Katrin Kogman-Appel, Illuminated Haggadot from Medieval Spain. Biblical Imagery and the Passover Holiday (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006), pp. 47–88.

- Ilana Tahan, Hebrew Manuscripts: The Power of Script and Image (London, British Library, 2007), pp. 94–97.

- Sacred: Books of the Three Faiths: Judaism, Christianity, Islam (London: British Library, 2007), p. 172 [exhibition catalogue].

- Marc Michael Epstein, The Medieval Haggadah. Art, Narrative, and Religious Imagination (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2011), pp. 129–200.