Income inequality in India

Income inequality in India refers to the unequal distribution of wealth and income among its citizens. According to the CIA World Factbook, the Gini coefficient of India, which is a measure of income distribution inequality, was 35.2 in 2011, ranking 95th out of 157.[2] Wealth distribution is also uneven, with one report estimating that 54% of the country's wealth is controlled by millionaires, the second highest after Russia, as of November 2016.[3] The richest 1% of Indians own 58% of wealth, while the richest 10% of Indians own 80% of the wealth. This trend has consistently increased, meaning the rich are getting richer much faster than the poor, widening the income gap.[3] Inequality worsened since the establishment of income tax in 1922, overtaking the British Raj's record of the share of the top 1% in national income, which was 20.7% in 1939–40.[4]

The latest Oxfam International report titled "Survival of the Richest: The India Story" highlights significant income inequality in India. The richest 1% now own more than 40% of the country's total wealth, while the bottom 50% hold just 3%. The report also reveals a gender pay gap, with female workers earning only 63 paise for every 1 rupee earned by male workers. Additionally, healthcare costs push around 63 million Indians into poverty each year. India has 119 billionaires, whose fortunes have increased almost tenfold over the past decade. The report calls for higher taxes on the wealthy, increased spending on health and education, and measures to address gender and social inequality.[5][6][7] According to Union Government 's own submission to Supreme Court of India, widespread hunger has caused 65% of deaths of children under the age of 5 in 2022.[1]

According to a 2021 report by the Pew Research Center, India has roughly 1.2 billion lower-income individuals, 66 million middle-income individuals, 16 million upper-middle-income individuals, and barely 2 million in the high-income group.[8] According to The Economist, 78 million of India's population are considered middle class as of 2017, if defined using the cutoff of those making more than $10 per day, a standard used by the India's National Council of Applied Economic Research.[9] According to the World Bank, 93% of India's population lived on less than $10 per day, and 99% lived on less than $20 per day in 2021.[10]

Income gaps

[edit]According to Thomas Piketty, it is difficult to accurately measure wealth inequality in India because of large gaps in income tax data. Official data from 1997 to 2000 contained many inconsistencies, while no data was published between 2000 and 2012. Then, in 2013, official income tax figures showed that only 1% of Indians paid tax that year, while only 2% filed a tax return. This lack of reliable data makes it essentially impossible to make significant, numerical conclusions about income inequality in India.[11][12]

The report "Income and Wealth Inequality in India, 1922-2023: The Rise of the Billionaire Raj" by Thomas Piketty and colleagues highlights several important aspects of inequality in India. By 2022-23, the top 1% of the population controlled 22.6% of the national income and 40.1% of the nation's wealth, marking historically unprecedented levels. This concentration of income and wealth places India among the most unequal countries globally, with its top 1% holding a larger share of national income compared to countries like South Africa, Brazil, and even the United States. The report observes that inequality in India has been on the rise since the early 2000s, particularly with a significant concentration of wealth among the billionaire class, a phenomenon the authors term the "Billionaire Raj." To address this growing inequality, the authors advocate for better access to official data and greater transparency in economic reporting. They also recommend a comprehensive wealth tax on the ultra-rich, aimed at reducing extreme inequality while creating fiscal space for increased social sector investments.[13][14][15]

Since much of the population is not represented in income-tax databases, most of the calculations (such as NSSO) are based on consumption-expenditure data instead of income data.[16] According to the World Bank, the Gini coefficient in India was 0.339 in 2009,[17] down from previous values of 0.43 (1995–96) and 0.45 (2004–05).[18] However, in 2016, the International Monetary Fund, in its regional economic outlook for Asia and the Pacific, said that India's Gini coefficient rose from 0.45 (1990) to 0.51 (2013).[19]

According to the 2015 World Wealth Report, India had 198,000 high-net-worth individuals with a combined wealth of $785 billion.[20]

Class divide

[edit]| Year | Minimum Net Worth (000 rupees) | Population |

|---|---|---|

| 1687 | 117 | 7000 |

| 1700 | 124 | 6,172 |

| 1725 | 124 | 6,820 |

| 1750 | 120 | 7,469 |

| 1775 | 120 | 8,117 |

| 1800 | 129 | 8,765 |

| 1825 | 128 | |

| 1850 | 128 | 4,605 |

| 1875 | 136 | 2,667 |

| 1900 | 228 | 3,104 |

| 1925 | 759 | 4,109 |

| 1950 | 2,057 | 4,968 |

| 1975 | 6,784 | 12,561 |

| 2000 | 49,457 | 43,267 |

| 2021 | 160,062 | 147,717 |

Credit Suisse’s Global Wealth Databook for 2014 reports that the bottom 10% of the Indian society owned merely 0.2% of national wealth,[21] while the richest 10% have been getting steadily richer since 2000.

| Social Class (%) | Wealth Share (%) |

|---|---|

| Bottom 10 | 0.2 |

| 10 - 20 | 0.4 |

| 20 - 30 | 0.8 |

| 30 - 40 | 1.3 |

| 40 - 50 | 1.8 |

| 50 - 60 | 2.6 |

| 60 - 70 | 3.8 |

| 70 - 80 | 5.7 |

| 80 - 90 | 9.4 |

| Top 10 Top 1 | 74 41 |

Causes

[edit]N. C. Saxena, a member of the National Advisory Council, suggested that the widening income disparity can be accounted for by India's badly shaped agricultural and rural safety nets. "Unfortunately, agriculture is in a state of collapse. Per capita food production is going down. Rural infrastructure such as power, road transport facilities are in a poor state," he said. "All the safety net programmes are not working at all, with rural job scheme and public distribution system performing far below their potential. This has added to the suffering of rural India while market forces are acting in favour of urban India, which is why it is progressing at a faster rate."[22]

Impact

[edit]India's economy continues to grow with its GDP rising faster than most nations. But a rise in national GDP is not indicative of income equality in the country. The growing income inequality in India has negatively impacted poor citizens' access to education and healthcare. Rising income inequality makes it difficult for the poor to climb up the economic ladder and increases their risk of being victims to poverty trap.[23] People living at the bottom 10% are characterized by low wages; long working hours; lack of basic services such as first aid, drinking water and sanitation.[18][24][25]

References

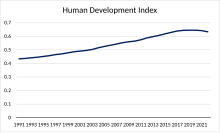

[edit]- ^ a b "Human Development Index". Human Development Reports. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Country Comparison - Gini Index". cia.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ a b "India second most 'unequal' country after Russia: Report". dailypioneer.com. 4 September 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ From British Raj to Billionaire Raj, Economic and Political Weekly, 7 October 2017

- ^ https://www.oxfam.org/en/india-extreme-inequality-numbers

- ^ https://indianexpress.com/article/business/economy/indias-richest-1-own-more-than-40-of-total-wealth-oxfam-8384156/

- ^ https://d1ns4ht6ytuzzo.cloudfront.net/oxfamdata/oxfamdatapublic/2023-01/India%20Supplement%202023_digital.pdf?kz3wav0jbhJdvkJ.fK1rj1k1_5ap9FhQ

- ^ "In the pandemic, India's middle class shrinks and poverty spreads while China sees smaller changes". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

The poor live on $2 or less daily, low income on $2.01-$10, middle income on $10.01-$20, upper-middle income on $20.01-$50 and high income on more than $50. All dollar figures are expressed in 2011 prices and purchasing power parity dollars, currency exchange rates adjusted for differences in the prices of goods and services across countries.

- ^ "India's missing middle class". The Economist. 11 January 2018. Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ "Poverty and Inequality Platform". World Bank. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 2022-05-17.

- ^ Rowlatt, Justin (2 May 2016). "'Indian inequality still hidden'". BBC.

- ^ "Income Inequality and Progressive Income Taxation in China and India, 1986–2015" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017.

- ^ https://wid.world/www-site/uploads/2024/05/WorldInequalityLab_2024_Torwards-Tax-Justice-Wealth-Redistribution-in-India_Issue-Brief.pdf

- ^ https://wid.world/www-site/uploads/2024/03/WorldInequalityLab_WP2024_09_Income-and-Wealth-Inequality-in-India-1922-2023_Final.pdf

- ^ https://frontline.thehindu.com/news/inequality-rising-since-2000s-top-one-per-cent-in-india-holds-40-per-cent-wealth-world-inequality-lab-study-ambani-adani/article67975819.ece

- ^ https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/wp2015-025.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "GINI index (World Bank estimate) - Data". data.worldbank.org.

- ^ a b "India still suffers from huge income gap". southasia.oneworld.net. Archived from the original on 2019-05-20. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ^ Nair, Remya (3 May 2016). "IMF warns of growing inequality in India and China". Livemint.

- ^ "World Wealth Report - Compare the data on a global scale". The Wealth Reports. Leading with Global Insights. The Industry Recognized Benchmark for Wealth Management Trends. www.worldwealthreport.com.

- ^ S, Rukmini (8 December 2014). "India's staggering wealth gap in five charts". The Hindu.

- ^ "Income gap rises in India: NSSO". Livemint. Archived from the original on 2019-03-02. Retrieved 2011-09-23.

- ^ "Does income inequality hurt economic growth? — Quartz". qz.com. 16 December 2016. Retrieved 2018-09-26.

- ^ http://thewire.in/39495/as-nda-govt-celebrates-two-years-a-citizens-report-underscores-its-failures-on-social-issues/ Citizens' Report Underscores Modi Government Failures on Social Issues

- ^ "'Reckless disinvestment in PSUs has exposed BJP's capitalistic mindset'". The Hindu. 23 October 2016.