Olorotitan

| Olorotitan Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Neornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ornithopoda |

| Family: | †Hadrosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Lambeosaurinae |

| Tribe: | †Lambeosaurini |

| Genus: | †Olorotitan Godefroit et al., 2003 |

| Type species | |

| †Olorotitan arharensis Godefroit et al., 2003 | |

Olorotitan was a monotypic genus of lambeosaurine duck-billed dinosaur, containing a single species, Olorotitan arharensis. It was among the last surviving non-avian dinosaurs to go extinct during the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, having lived from the middle to late Maastrichtian-age of the Late Cretaceous era. The remains were found in the Udurchukan Formation beds of Kundur, Arkharinsky District, Amur Oblast, Eastern Russia, in the vicinity of the Amur River.

Discovery and naming

[edit]

The holotype specimen of Olorotitan, consisting of a nearly complete skeleton, was discovered in field work in the Udurchukan Formation of Kundur in the Amur region of Russia between 1999 and 2001. Pascal Godefroit and colleagues described and named it as a new species in 2003. It was the first nearly complete dinosaur specimen to be described from Russia, and is the most complete lambeosaurine skeleton discovered anywhere outside of western North America.[1]

Large numbers of fragmentary dinosaur, turtle, and crocodilian specimens were found in the several hundred square metre area around the discovery site. Similarly aged localities in Blagoveschensk, also from the Udurchukan Formation and Jiayin, on the Chinese side of the Amur River, have yielded similarly high numbers of lambeosaurine fossils.[1]

The generic name Olorotitan means "titanic swan" because its neck is longer when compared with other hadrosaurs, while the specific descriptor arharensis refers to Arhara County where the fossil was found.[1]

Description

[edit]

Olorotitan arharensis is based on the most complete lambeosaurine skeleton found outside North America to date. It was a large hadrosaurid, comparable with other large lambeosaurines such as Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus,[1] and may have grown up to 8 metres (26 ft) in length, up to 3.5 metres (11 ft) in height and within the range of 2.6–3.4 metric tons (2.9–3.7 short tons) in body mass.[2][3]

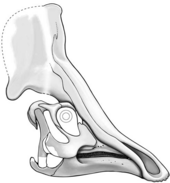

It is characterized by the large hatchet-like hollow crest adorning its skull, very distinct from the crests of all of its North American relatives. The skull itself was supported by a rather elongated neck, having eighteen vertebrae, exceeding the previous hadrosaurid maximum of fifteen. The sacrum, with 15 or 16 vertebrae, has at least 3 more vertebrae than other hadrosaurids. Further along the vertebral series, in the proximal third of the tail, there are articulations between the tips of the neural spines, making that caudal area particularly rigid; the regularity of these connections suggests that they are not due to a pathology, although more specimens are needed to be certain. Godefroit and his coauthors found through a phylogenetic analysis that it was closest to Corythosaurus and Hypacrosaurus.[1]

Palaeobiology

[edit]

As a hadrosaurid, Olorotitan would have been a bipedal/quadrupedal herbivore, eating plants with a sophisticated skull that permitted a grinding motion analogous to chewing, and was furnished with hundreds of continually-replaced teeth. Its tall, broad hollow crest, formed out of expanded skull bones containing the nasal passages, probably functioned in identification by sight and sound.[4]

Palaeoecology

[edit]

O. arharensis shared its time and place with several other types of animal, including two other lambeosaurines: the Parasaurolophus-like Charonosaurus and more basal Amurosaurus. Additionally, remains from turtles, crocodilians, theropods, and nodosaurids were found at its discovery site,[1] and the Saurolophus-like hadrosaurine Kerberosaurus is also known from roughly contemporaneous rocks in the area.[5] Unlike the situation in North America, where lambeosaurines are virtually absent from Late Maastrichtian rocks, Asian lambeosaurines are diverse and common at the end of the Mesozoic, suggesting climatic or ecological differences.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Godefroit, Pascal; Bolotsky, Yuri; Alifanov, Vladimir (2003). "A remarkable hollow-crested hadrosaur from Russia: an Asian origin for lambeosaurines" (PDF). Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2 (2): 143–151. Bibcode:2003CRPal...2..143G. doi:10.1016/S1631-0683(03)00017-4.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 309. ISBN 9780691137209.

- ^ Godefroit, P.; Bolotsky, Y. L.; Bolotsky, I. Y. (2012). "Osteology and Relationships of Olorotitan arharensis, A Hollow-Crested Hadrosaurid Dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Far Eastern Russia". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 57 (3). Institute of Paleobiology, Polish Academy of Sciences: 527–560. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0051. S2CID 54197398.

- ^ Horner, John R.; Weishampel, David B.; Forster, Catherine A (2004). "Hadrosauridae". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 438–463. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ^ Bolotsky, Y.L.; Godefroit, P. (2004). "A new hadrosaurine dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Far Eastern Russia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (2): 351–365. Bibcode:2004JVPal..24..351B. doi:10.1671/1110. S2CID 130691286.