Parkend

| Parkend | |

|---|---|

Parkend (2009) | |

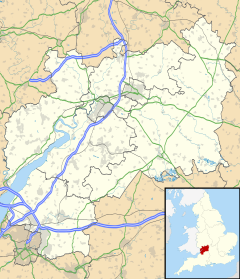

Location within Gloucestershire | |

| OS grid reference | SO615082 |

| • London | 105.86 mi (170.37 km) |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LYDNEY |

| Postcode district | GL15 |

| Dialling code | 01594 |

| Police | Gloucestershire |

| Fire | Gloucestershire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | West Dean Parish Council |

Parkend is a village, located at the foot of the Cannop Valley, in the Royal Forest of Dean, West Gloucestershire, England, and has a history dating back to the early 17th century. During the 19th century it was a busy industrial village with several coal mines, an ironworks, stoneworks, timber-yard and a tinplate works, but by the early 20th century most had succumbed to a loss of markets and the general industrial decline. In more recent times, the village has become a tourist destination.

Amenities

[edit]The village has two public houses, both with guest accommodation, and one with an adjoining hostel; The Fountain Inn and Lodge[1] and The Woodman Inn.[2] There are also two guesthouses, several holiday let properties, a CIU affiliated club with caravan & camping facilities, and a large camping and caravan site named Whitemead Forest Park;[3] owned and operated by the Civil Service Motoring Association (C.S.M.A.).[4] The Dean Field Studies Centre, once part of Parkend Ironworks, is owned by Bristol City Council and is used to accommodate schoolchildren from that city.[5]

The village and parish church are dedicated to St Paul and situated on the eastern edge of the village in a forest clearing. The shape provides the point of interest, being both octagonal and cruciform, with the arms formed by the sanctuary, north and west transepts and the west tower. It was designed and built in 1822,[6] together with the village school, by Henry Poole;[7] a local priest who raised most of the money through public subscription and his own generosity.

Sport and Recreation

[edit]

Parkend Cricket Club is an English amateur cricket club that is based on the northern edge of the village on Crown Lane.[8] Parkend have 2 Saturday senior XI teams.[9] The 1st XI compete in the Gloucestershire County Cricket League,[10] and the 2nd XI are in the Cheltenham, Gloucester and Forest of Dean League.[11] They also have a Midweek senior XI team that traditionally took part in the annual West Gloucestershire Cricket Federation "Verderers Cup" competition,[12] and a Sunday XI team that currently play the occasional friendly against neighbouring clubs. The Parkend juniors all play competitive cricket in the Leadon Vale Youth Cricket League.[13]

The Parkend Players is an Amateur theatre group that performs most of its shows at the village Memorial Hall.

Parkend Carnival, held on August Bank Holiday Monday, is renowned throughout the forest as being the biggest and best for miles around.[14]

During the summer, regular Sunday car boot sales are held on the recreation field, the profits from which go to support the Memorial Hall.

The village also has a very active Women's Institute.

RSPB Nagshead

[edit]

Located on the western edge of the village, RSPB Nagshead is a quiet reserve, open all year. Facilities include a visitor centre, large car park, two viewing hides, two way-marked walks, and a picnic area. Birdlife regularly seen in the reserve includes great spotted woodpecker, Eurasian nuthatch, northern goshawk and common buzzard. Breeding birds include common redstart, pied flycatcher, and common crossbill and wood warbler, whilst Redwing, hawfinch and Eurasian woodcock can be found in winter.[15]

In 1942, nest boxes were erected, in the hope that pied flycatchers would control oak leafroller moths, which were defoliating trees. These boxes have been continually monitored since 1948, making it the world's longest running bird breeding programme.

Parkend railway station

[edit]

The railway in Parkend began life in 1810, as a horse-drawn tramroad, owned and operated by the Severn and Wye Railway Co. By 1874, the line had been converted to run standard gauge steam locomotives and the station was built in 1875 to enable the company to also run passenger services alongside its freight operations.[16] The level crossing gates by the station are reputedly the longest in Britain.

A decline in coal production and a reduction in passengers saw the station close to regular passenger services in 1929. The last goods train left Parkend on 26 March 1976 and much of the track was dismantled.[17] The line was bought by the Dean Forest Railway, based at Norchard, and Parkend was officially re-opened on Friday 19 May 2006 by the Princess Royal.[18] The station is currently the northern terminus of the Dean Forest Railway.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The earliest evidence of human activity in Parkend comes from a hoard of over 1,000 Roman coins, found in the village in 1852, and dating from around AD 300.[19] A lack of other artefacts from the period suggests that the Romans probably did not settle there. History is then silent until 1278, and the first record of a hunting enclosure called ‘Wistemede’ - later known as Whitemead Park. The village's location, at one end of this park, is how Parkend derived its name.

In 1612 James I built a charcoal-fired blast furnace and forge at ‘Parke End’, bringing with it the first real settlement, however, ‘The King’s Ironworks’ proved horrendously inefficient and it closed in 1674.[20] It would seem that occupation of the village then ceased until new dwellings appeared from 1747 onwards. Part of the Fountain Inn dates back to 1767 and is the oldest surviving building in Parkend. The first record of a coal mine in Parkend dates back to 1718, although the remains of several bell pits, possibly dating back to the 1600s, are visible in the woods south-west of St Paul's church.[21]

Industrialisation and growth of the village

[edit]With the advent of coke-fired furnaces, Parkend, and its many coal mines, was once again considered an ideal location for the production of iron. In 1799 a new ironworks was constructed near the site of the current post office. Initially it suffered from technical problems, but by the early/mid-1800s it had triggered a major industrialisation of the village.

The need for improved transport links was instrumental in the construction of a horse-drawn tramroad by the Severn & Wye Railway Co in 1810, connecting the village with the docks at Lydney. Demand for coal at the ironworks also lead to the appearance of several large coal mines in the village during the early 1800s, the most notable being 'Castlemain'.

In 1818/9 another ironworks was also built at Darkhill, just to the west of Parkend, and in 1845 Robert Forester Mushet took over management of the site. One of his greatest achievements was to perfect the Bessemer Process by discovering the solution to early quality problems which beset the process.[22] In a second key advance in metallurgy Mushet invented 'R Mushet's Special Steel' (R.M.S.) in 1868.[23] It was both the first true tool steel[23] and the first air-hardening steel.[24] It revolutionised the design of machine tools and the progress of industrial metalworking, and was the forerunner of High speed steel. The remains of Darkhill are now preserved as an Industrial Archaeological Site of International Importance and are open to the public.[25]

In 1825, the lower pond at Cannop and a 1½ mile leat were constructed to provide a constant supply of water to a waterwheel at Parkend Ironworks.[26] Despite the enormous effort expended in creating this supply, it proved inadequate and an engine house and steam engine were added in 1828. A second pond at Cannop was also constructed a year later.

The school and St Paul’s church were built in 1822 and Henry Poole, who had designed both, became Parkend’s first vicar. He moved into the new vicarage in 1829, but the school developed structural problems and was rebuilt, on the same site, in 1845.

A stone works opened in 1850 and a tinplate works was constructed in 1853. It stood to the left of the ironworks, and further along was built a row of terraced houses, known as ‘The Square’, which were used to accommodate the workers there.

In 1864 the Severn and Wye Railway Company began operating steam locomotives on the existing tramway. This proved to be unsatisfactory and 1868 the company also added a broad-gauge steam railway line, but both were removed and replaced with standard gauge tracks by 1874. At around the same time, a loading wharf, known as Marsh Sidings, was constructed and Parkend railway station opened in 1875, allowing the company to also operate passenger trains alongside its freight operations.[16]

In 1871 a third furnace was added at Parkend Ironworks, but the optimism behind this investment was to be short-lived.

Periods of industrial decline

[edit]During the mid-1870s, industry in the Forest, and across the country as a whole, quickly began to slide into a deep recession. Parkend Tinplate Works, and the ironworks that had dominated the village for 90 years, succumbed to a loss of markets and both closed in 1877. Just a few years before, these two businesses alone had been employing 500 people between them, but even this was overshadowed by the closure of the Parkend coal pits in 1880, which went into voluntary liquidation with the loss of 700 jobs.

By the mid-1880s, the industrial decline that had gripped the Forest was beginning to ease. The mines, which had closed in 1880, reopened in 1885 and by the 1890s they were prospering once again. The ironworks did not re-open and were demolished by 1909, although the imposing engine-house survived to become the country’s first Forester Training School in 1910.

The 1920s proved to be another difficult period for the residents of Parkend. The high demand for coal, that had been created by the First World War, was followed by a slump and industrial unrest. Matters were made worse as the local mines were now finding it difficult to access coal easily, and some had been worked out completely. There were major strikes in 1921 and 1926, and all the village mines, except New Fancy, finally closed for the last time in 1929. There was a considerable knock-on effect for other industries too and the railway closed to passengers in the same year. Parkend stone works closed in 1932, marking the end of heavy industry in the village.

Modern history

[edit]The Forester Training School was commandeered by the War Office during WWII and used as a barracks by the American army.[27] After the war it reverted to being a forestry school until it was bought by Avon County Council in 1972, for use as a field-studies centre, and regularly hosts groups of school children.

The houses known as ‘The Square’ were demolished in the mid-1950s and their occupants re-housed in a new council estate. Another housing development, of 26 dwellings, was built near the railway station, in 2004.

Whitemead Park, which had been the Forestry Commission’s headquarters since 1814, was bought by the Civil Service Motoring Association in 1970. It opened as a caravan site in 1971 and is now the largest tourist accommodation facility in the forest.

Freight operations by the railway continued at Marsh Sidings up until 1976, after which much of the track was dismantled. The line was bought by the Dean Forest Railway Preservation Society and Parkend station was officially re-opened by princess Anne on 19 May 2006.[28]

Notable residents

[edit]- Warren James (1792–1841) - Miners' leader who led the Foresters to action against the Crown, in 1831. Born on the southern edge of Parkend.[19]

- Jolly John Nash (1828–1901) - Colliery proprietor who became a leading music hall entertainer in London.[29]

- Robert Deakin (1917-1985) - Anglican Bishop of Tewkesbury. Born in the village.[30]

- Mary Rose Young (born 1958) - Internationally renowned ceramic artist, lives and works in the village.[31]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Fountain Inn & Lodge". Fountain Inn & Lodge. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "The Woodman Inn". The Woodman Inn. Archived from the original on 10 April 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Whtiemead Forest Park". Whtiemead Forest Park. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Edmondson, Donald (2003). Whitemead Park a short history. A CSMA Leisure Property. pp. 12–13.

- ^ "Dean Field Studies Centre". Bristol City Council. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "About Our Churches". Parkend and Viney Hill Churches. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Church of St Paul". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Parkend CC". parkend.play-cricket.com. Parkend Cricket Club. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Parkend Cricket Club Teams". parkend.play-cricket.com. Parkend Cricket Club. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Gloucestershire County Cricket League". gloucestershireccl.play-cricket.com. Gloucestershire County Cricket League. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Cheltenham, Gloucester and Forest of Dean League". cgfleague.play-cricket.com. Cheltenham, Gloucester and Forest of Dean League. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Verderers Cup competition". westgloucscf.play-cricket.com. West Gloucestershire Cricket Federation. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Leadon Vale Youth Cricket League". leodonvaleycl.play-cricket.com. Leadon Vale Youth Cricket League. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Parkend Carnival". Parkend Carnival. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Nagshead". RSPB. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Parkend, Forest of Dean". Roger Farnworth. 29 September 2017. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Gloucestershire's lost railways stations and the long lost lines". Gloucestershire Live. February 2020. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Modern History". Parkend Village. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Early History". Parkend Village. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Parkend". DEanweb. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Forest of Dean: Industry Pages 326-354 A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 5, Bledisloe Hundred, St. Briavels Hundred, the Forest of Dean". British History Online. Victoria County History. Archived from the original on 27 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Anstis, Ralph (1997). Man of Iron, Man of Steel: Lives of David and Robert Mushet. Albion House. p. 140. ISBN 978-0951137147.

- ^ a b Robert Mushet, archived from the original on 26 July 2009, retrieved 27 May 2009

- ^ Stoughton, Bradley (1908). The Metallurgy of Iron and Steel. pp. 408–409. ISBN 978-1112218781.

- ^ Anstis, Ralph (1997). Man of Iron, Man of Steel: Lives of David and Robert Mushet. Albion House. ISBN 978-0951137147.

- ^ "Cannop Ponds". Forestry Commission. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "The Forester Training School, Parkend". Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research. 28 (1): 48. 1955. doi:10.1093/forestry/28.1.48. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Anstis, Ralph (2009). The Story of Parkend: A Forest of Dean Village. Lightmoor Press. ISBN 978-1899889044.

- ^ Mary Atkins, "'Jolly' John Nash: A Forest 'Lion Comique'", The New Regard: Journal of the Forest of Dean Local History Society, No.23, 2009, pp.60-64

- ^ "St. Paul's Church, Parkend". Parkend and Viney Hill Churches. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Mary Rose Young". Mary Rose Young. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

Gallery

[edit]- Click on image for larger view

- Level crossing near Parkend Station.

- Parkend Primary School.

- The Dean Field Studies Centre, formerly part of Parkend Ironworks.

- The Fountain Inn.

- The 'Royal Forester' at Parkend Station.

- The Memorial Hall.

- The Pike House, at the junction of Bream and Coleford Roads.

- St Paul's Church.

- The Baptist Chapel.

- Mary Rose Young pottery and gallery.

- The cycle path in Parkend.

- Edward VII lime trees in the village.

- Runic script on an 1886 gravestone in Parkend churchyard.

- Stylised mural of the miners' leader Warren James, in the Fountain Inn.