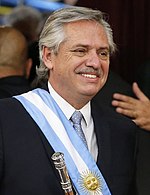

Presidency of Alberto Fernández

| |

| Presidency of Alberto Fernández 10 December 2019 – 10 December 2023 | |

Alberto Fernández | |

| Party | Justicialist Party (PJ) Frente de Todos |

| Election | 2019 |

| Seat | Casa Rosada Quinta de Olivos |

| | |

The Presidency of Alberto Fernández began on 10 December 2019, when Alberto Fernández was sworn into office to a four-year term as President of Argentina. Fernández took office alongside vice president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner following the Frente de Todos coalition's victory in the 2019 general election, with 48.24% of the vote against incumbent president Mauricio Macri's 40.28%. Fernández's victory represented the first time in Argentina's history that an incumbent president had been defeated in a re-election bid.[1] In 2023, he was later succeeded by Javier Milei.

2019 election

[edit]On 18 May 2019, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner announced that Fernández would be a candidate for president and that she would run for vice president alongside him, hosting his first campaign rally with Santa Cruz Governor Alicia Kirchner, sister-in-law of the former Kirchner.[2][3]

About a month later, seeking to broaden his appeal to moderates, Fernández struck a deal with Sergio Massa to form an alliance called Frente de Todos, wherein Massa would be offered a role within a potential Fernández administration, or be given a key role within the Chamber of Deputies in exchange for dropping out of the presidential race and offering his support.[4] Fernández also earned the endorsement of the General Confederation of Labour, receiving their support in exchange for promising that he will boost the economy and that there would be no labor reforms.[5]

Inauguration

[edit]Fernández took office on 10 December 2019. The ceremony took place, as it is constitutionally mandated, in the palace of the National Congress of Argentina. He was accompanied by his domestic partner, Fabiola Yáñez, and his only child, Tani Fernández. At midday, Fernández was sworn in alongside Vice President-elect Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, in the presence of Macri, Vice President (and president of the Senate) Gabriela Michetti, the General Assembly (the congregation of both houses of Congress), and domestic and international dignitaries.[6]

Cabinet

[edit]Fernández's cabinet took office on the same day he was sworn in as president, on 10 December 2019.[7] The cabinet is formed by members of the Frente de Todos, a peronist coalition formed ahead of the 2019 general election, as well as independents.[8] Reflecting the composition of the Frente de Todos, it was made up of members belonging to different branches of the Justicialist Party, members of the Renewal Front, and independents.

The first change in the cabinet took place in November 2020, when María Eugenia Bielsa was replaced by Jorge Ferraresi as Minister of Habitat.[9] Ginés González García, Minister of Health, was sacked in February 2021 and replaced by vice-minister Carla Vizzotti following a scandal regarding preferential treatment in the COVID-19 vaccination campaign.[10] The Justice Minister, Marcela Losardo, resigned in March 2021 for personal reasons and was replaced by congressman Martín Soria.[11]

Ahead of the 2021 legislative elections, the ministers of defense (Agustín Rossi) and social development (Daniel Arroyo) announced their candidacies for legislative positions; they were replaced by Jorge Taiana and Juan Zabaleta, respectively, in August 2021.[12] Following the governing coalition's poor showings in the September 2021 primary elections, President Fernández organised a cabinet reshuffle that resulted in changes in the portfolios of foreign affairs, security, agriculture, education, science and technology, and the Cabinet Chief's Office.[13][14]

Ministers

[edit]Presidential secretariats

[edit]| Ministry | Minister | Party | Start | End | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Secretary | Julio Vitobello | Justicialist Party | 10 December 2019 | 10 December 2023 | |

| Legal and Technical Secretary | Vilma Ibarra | Independent | 10 December 2019 | 10 December 2023 | |

| Secretary of Strategic Affairs | Gustavo Béliz | Independent | 10 December 2019 | 29 July 2022 | |

| Mercedes Marcó del Pont | MID | 1 August 2022 | 10 December 2023 | ||

| Secretary of Communications and Press | Juan Pablo Biondi | Justicialist Party | 10 December 2019 | 20 September 2021 | |

| Juan Ross | Independent | 20 September 2021 | 10 December 2023 | ||

Domestic affairs

[edit]Economic policy

[edit]

On 14 December 2019, the government established by decree the emergency in occupational matters and double compensation for dismissal without just cause for six months.[16]

Fernández's first legislative initiative, the Social Solidarity and Productive Recovery Bill, was passed by Congress on 23 December 2019.[17] The bill includes tax hikes on foreign currency purchases, agricultural exports, wealth, and car sales - as well as tax incentives for production. Amid the worst recession in nearly two decades, it provides a 180-day freeze on utility rates, bonuses for the nation's retirees and Universal Allocation per Child beneficiaries, and food cards to two million of Argentina's poorest families. It also gave the president additional powers to renegotiate debt terms – with Argentina seeking to restructure its US$100 billion debt with private bondholders and US$45 billion borrowed by Macri from the International Monetary Fund.[17] As the capital controls stayed in effect and with no prospect of being removed, the MCSI degraded the country from emerging market to standalone market.[18]

Organisations of the agricultural sector, including Sociedad Rural Argentina, CONINAGRO, Argentine Agrarian Federation and Argentine Rural Confederations, rejected the increase in taxes on agricultural exports. Despite these conflicts, Fernández announced the three-point increase in withholding tax on soybeans on the day of the opening of the regular sessions, on 1 March and generated major problems in the relationship between the government and the agricultural sector.[19][20]

At the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, the IMF reported that Argentina's GDP would plunge by 9.9 percent, after the country's economy contracted by 5.4 percent in first quarter of 2020, with unemployment rising over 10.4 percent in the first three months of the year, before the lockdown started.[21][22][23] On September 22, as part of the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, official reports showed a 19% year-on-year drop in the GDP for the second quarter of 2020, the biggest drop in the country's history.[24][25] Investment went down 38% from the previous year.[24][25] The poverty rate rose to 42% in the second half of 2020, the highest since 2004.[26] Child poverty reaches the 57.7% of minors of 14 years.[26]

Debt restructuring and agreement with the IMF

[edit]In 2018, under the Mauricio Macri administration, Argentina received the International Monetary Fund (IMF)'s biggest loan to date: $57 billion US$ were initially greenlit by the international organisation.[27] Following Macri's defeat in the 2019 election, Fernández's economy minister, Martín Guzmán, announced the incoming administration would not request the final installment of the IMF's loan, accounting for $11 billion.[28]

Argentina defaulted again on 22 May 2020 by failing to pay $500 million on its due date to its creditors. Negotiations for the restructuring of $66 billion of its debt continued after that.[29] On August 4, Fernández reached an accord with the biggest creditors on terms for a restructuring of $65bn in foreign bonds, after a breakthrough in talks that had at times looked close to collapse since the country's ninth debt default in May.[30]

In 2021, the International Monetary Fund concluded the 2018 loan granted to Macri's administration "had not delivered on its objectives". The Fernández administration has maintained its criticism of the deal, with Guzmán calling it "an absurd loan".[31]

On 28 January 2022, the Fernández administration struck an agreement in principle with the International Monetary Fund over a new $44.5 billion standby deal.[32] The deal, which requires congressional approval in order to take effect, caused unease within the governing coalition. Máximo Kirchner, president of the Frente de Todos parliamentary bloc in the Chamber of Deputies and leader of La Cámpora, one of the coalition's largest partners, resigned from his position on 1 February 2022 over disagreements with the IMF deal.[33]

COVID-19 pandemic

[edit]

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Fernández administration announced a country-wide lockdown, in effect from 20 March until 31 March, later extended until 12 April.[35][36] The lockdown was further renewed on April 27, May 11, May 25, June 8, July 1, July 18, August 3, August 17, August 31 and September 21, and included several measures including travel, transport and citizen movement restrictions, stay-at-home orders, store closures and reduced operating hours.[37]

Responses to the outbreak have included restrictions on commerce and movement, closure of borders, and the closure of schools and educational institutions.[38] The announcement of the lockdown was generally well received, although there were concerns with its economic impact in the already delicate state of Argentina's economy, with analysts predicting at least 3% GDP decrease in 2020.[39][40] Fernandez later announced a 700 billion pesos (US$11.1 billion) stimulus package, worth 2% of the country's GDP.[39][41][42] After announced a mandatory quarantine to every person that returned to Argentina from highly affected countries,[43][44] the government closed its borders, ports, and suspended flights.[38][45]

On 23 March, Fernández asked the Chinese president Xi Jinping for 1,500 ventilators as Argentina had only 8,890 available.[46][47]

Despite the government's hard lockdown policy, Fernández was criticised[48] for not following the appropriate protocols himself. This included traveling throughout the country, taking pictures with large groups of supporters without properly wearing a mask nor respecting social distancing,[49] and holding social gatherings with union leaders.[50]

On 3 September 2020, despite most local governments still enforcing strict lockdown measures, Fernández stated that "there is no lockdown",[51] and that such thoughts had "been instilled by the opposition", as part of a political agenda.[52] Fernández eased some lockdown measures in the Greater Buenos Aires on 6 November 2020, shifting to a "social distancing" phase.[53][54]

Economic impact

[edit]Due to the national lockdown, economic activity suffered a collapse of nearly 10% in March 2020 according to a consultant firm. The highest drop was in the construction sector (32%) versus March 2019. Every economic sector suffered a collapse, with finance, commerce, manufacturing industry, and mining being the most affected. The agriculture sector was the least affected, but overall the economic activity for the first trimester of 2020 accumulated a 5% contraction. It is expected that the extension of the lockdown beyond April would increase the collapse of the Argentinian economy.[55] On March, the primary fiscal deficit jumped to US$1,394 million, an 857% increase year-to-year. This was due to the public spending to combat the pandemic and the drop in tax collection due to low activity in the context of social isolation.[56] Schools were closed for over a year, and it is estimated that 1.5 million of kids abandoned school, a 13% of the total.[57]

Because banks were excluded in the list of businesses that were considered essential in the lockdown decree, they remained closed until the Central Bank announced banks would open during a weekend starting on 3 April.[58] Due to Argentina's notoriously low level of banking penetration, many Argentines, particularly retirees, do not possess bank accounts and are used to withdraw funds and pensions in cash.[59] The decision to open banks for only three days on a reduced-hours basis sparked widespread outrage as hundreds of thousands of retirees (coronavirus' highest risk group) flocked to bank branches in order to withdraw their monthly pension and emergency payment.[60][61][62][63]

Vaccination campaign

[edit]

On 21 January 2021, Fernández became the first Latin American leader to be inoculated against the disease via the recently approved Gam-COVID-Vac (better known as Sputnik V).[64][65] On 7 December 2021, Fernández received his booster dose of the vaccine.[66]

Ginés González García was forced to resign as Health Minister on 19 February 2021[10][67] after it was revealed he provided preferential treatment for the COVID-19 vaccine to his close friends, including journalist Horacio Verbitsky and other political figures. He was succeeded by the second in charge Carla Vizzotti. The revelation was met with wide national condemnation from supporters and opposition, as Argentina had at the time received only 1,5 million [68] doses of vaccine for its population of 40 million.[69]

Fernández tested positive for COVID-19 on 2 April 2021 having a "light fever".[70]

By January 2022, 86.2% of the country's population had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, while 74.5% had received the respective two doses of the vaccine.[71] Booster shots started being given to vulnerable populations in October 2021.[72]

Social policy

[edit]In September 2019, during the Mauricio Macri administration, the Argentine Congress declared a "National Hunger Emergency".[73] As one of his initial measures as president, Fernández launched the Plan Argentina contra el Hambre ("Argentina against Hunger Plan").[74] As part of the plan, the Social Development Ministry began issuing Tarjeta Alimentar cards, debit cards assigned 4,000 pesos per month (later adjusted to 6,000 pesos)[75] to beneficiaries of the existing Universal allocation per child (AUH) programme to be used in food items.[76] In addition, the programme implemented price caps for essential food items ("Precios Cuidados") and value-added tax returns for low-income households.[77]

At the onset of the economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdown measures, the Fernández administration launched two complimentary social assistance schemes: the Ingreso Familiar de Emergencia ("Emergency Family Income", IFE) and the Asistencia de Emergencia al Trabajo y la Producción ("Emergency Labour and Production Assistance", ATP). The IFE programme granted 10,000 monthly pesos to informal sector workers and self-employed workers whose income was affected by the lockdown. In total, over 8 million people across the country during two months, and later continued to be issued for people living in urban centres where lockdown measures continued in place throughout 2020. On the other hand, the ATP programme granted half of the salaries of workers (active or otherwise) for a number of businesses.[78] Lastly, the government forbid all terminations and unilateral suspensions of labour contracts for 120 days, later extending the measure to cover all of 2020 and 2021.[79]

Social issues

[edit]Following his victory in the 2019 elections, Fernández announced his cabinet would include, for the first time in Argentina's history, a ministry dedicated entirely to deal with women's affairs. Elizabeth Gómez Alcorta was appointed as the first Minister of Women, Genders and Diversity on 10 December 2019. Prior to the establishment of the Ministry, women's affairs were dealt by the National Institute for Women.[80]

Abortion

[edit]

On 31 December 2019, Fernández announced that he would send a bill in 2020 to discuss the legalisation of abortion, ratified his support for its approval, and expressed his wish for "sensible debate".[81] However, in June 2020, he stated that he was "attending to more urgent matters" (referring to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the debt restructuring), and that "he'll send the bill at some point".[82] In November 2020, Fernández's legal secretary, Vilma Ibarra, confirmed that the government would be sending a new bill for the legalisation of abortion to the National Congress that month.[83] The Executive sent the bill, alongside another bill oriented towards women's health care (the "1000 Days Plan"), on 17 November 2020.[84] The bill was passed by the Senate on 30 December 2020,[85] and received presidential assent on 14 January 2021, effectively legalising abortion in Argentina.[86]

LGBT rights

[edit]In January 2020, trans rights activist Alba Rueda was appointed Undersecretary of Diversity Policies (Spanish: "Políticas de Diversidad") within the new Ministry of Women, Genders and Diversity, becoming the first transgender person to be appointed to a senior government post in Argentina.[87]

On 4 September 2020, Fernández signed Decreto 721/2020, which established a 1% employment quota for trans and travesti people in the national public sector. The measure had been previously debated in the Chamber of Deputies as various prospective bills.[88] The decree mandates that at any given point, at least 1% of all public sector workers in the national government must be transgender, as understood in the 2012 Gender Identity Law.[89]

On 20 July 2021, Fernández signed another decree, Decreto 476/2021, mandating the National Registry of Persons (RENAPER) to allow a third gender option on all national identity cards and passports, marked as an "X". The measure applies to non-citizen permanent residents who possess Argentine identity cards as well.[90] In compliance with the 2012 Gender Identity Law, this made Argentina one of the few countries in the world to legally recognize non-binary gender on all official documentation.[91][92]

Security policy

[edit]Fernández first appointed anthropologist Sabina Frederic as security minister. Frederic positioned herself as a staunch opponent of previous security minister Patricia Bullrich's policies.[93] On 24 December 2019, the Ministry of Security published Resolution 1231/19, which reversed many of Bullrich's policies in the Ministry: previous protocols on firearm use by security forces were overturned, and a protocol on the use of taser guns was created. In addition, the resolution annulled the programme overseeing offenders in the railway system and the 1149 Protocol, which "allowed security forces to harm the rights of LGBT citizens".[94][95][96]

In April 2020, Frederic stated that the ministry would continue her predecessor's policy of cyber surveillance to measure "social humour"; these statements were widely criticized by social organizations and the Opposition.[97][98][99]

As one of his initial measures in the presidency, Fernández intervened the Federal Intelligence Agency (AFI), redirecting its budget to finance the government's plan against hunger.[100] Attorney Cristina Caamaño was designated as interventor of the AFI on 21 December 2019.[101] Under Fernández, the agency's powers and reach have been considerably reduced, and its files are undergoing a process of declassification to aid in the investigation of the 1994 AMIA bombing.[102]

Narcotics

[edit]On 12 November 2020, Fernández signed a decree legalizing the self-cultivation and regulating the sales and subsidized access of medical cannabis, expanding upon a 2017 bill that legalized the use and research of the plant and its derivatives.[103] In June 2019, during his presidential campaign, he had signaled his intention to legalize marijuana for recreational purposes, but not other types of drugs.[104]

In February 2022, a batch of laced cocaine distributed in Puerta 8, a villa miseria in Tres de Febrero, Buenos Aires Province caused up to 23 deaths and dozens of hospitalizations.[105] Police analyses concluded the cocaine had been tainted with opioids, resulting in a much higher rate of lethality.[106] The Buenos Aires Province government initially warned potential consumers to throw away any cocaine they may have acquired in the 24 hours prior to the first hospitalizations, hoping to reduce casualties.[107]

Foreign policy

[edit]

Fernández's first presidential trip abroad was to Israel in January 2020. There, he paid respects to the victims of the Holocaust and maintained a bilateral meeting with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu who thanked him for keeping Hezbollah branded as a terrorist organisation, a measure taken by former President Mauricio Macri.[108][109]

In January 2022, Fernández was elected president pro tempore of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), succeeding Mexico's Andrés Manuel López Obrador.[110][111]

Bolivia

[edit]Alberto Fernández questioned the conclusions of the Organization of American States that the reelection of Evo Morales was unconstitutional for electoral fraud. Fernández's government recognized Morales as the legitimate President of Bolivia and granted him asylum in Argentina in December 2019.[112][113] On 9 November 2020, following Luis Arce's victory in the 2020 Bolivian election, Fernández personally accompanied Morales to the Argentine border with Bolivia, wherein the two leaders held a public act celebrating Morales's return to his home country.[114]

Fernández met with Arce in the Chilean city of Viña del Mar on 11 March 2022. There, the presidents discussed a proposal to build a roadmap for cooperation between both countries by developing joint policies in the scientific and technological fields. On the issue of energy, both presidents took steps to conclude negotiations surrounding a Bolivian natural gas supply contract and agreed on the potential to advance electrical integration and interconnection between Yaguacuá, Tarija and Tartagal, Salta.[115]

Arce made an official visit to Buenos Aires on 7 April, where he held bilateral meetings with Fernández at the Casa Rosada. Their negotiations primarily surrounded the sale of natural gas, with Bolivia agreeing to ship fourteen million cubic meters (m3) of gas per day during the winter months. For this, Argentina agreed to pay between US$8 million and US$9 million for the first ten million m3, with the price doubling to US$18 million for the remaining four million m3. Although Argentina agreed to pay a higher price for the same volume of gas sent in 2021, it was still significantly less than what Buenos Aires would've paid to import liquefied natural gas by ship. Additionally, Bolivia agreed to prioritize Argentina for the delivery of a further four million m3 at a price of US$18 million should Brazil not need it.[116]

China

[edit]

In February 2022, during a state visit to China, Fernández formally signed Argentina's entry into the Belt and Road Initiative, finalizing an accession process that had begun during the presidency of Mauricio Macri.[117][118] In addition, Fernández attended the 2022 Winter Olympics opening ceremony.[119] During the same international tour, Fernández met Russian president Vladimir Putin in Moscow and Barbadian prime minister Mia Mottley in Barbados.[120][121]

BRI-based investments in Argentina include over $8,000 million US$ for a new nuclear power plant in the existing Atucha Nuclear complex. Atucha III (as the project has been dubbed) is expected to become Argentina's fourth nuclear power plant, and will create 7,000 new jobs in the sector.[122]

Falkland Islands

[edit]On 3 January 2020, three weeks into the Fernández presidency, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Worship issued a statement ratifying Argentina's historic claim to sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas), the South Georgia Islands, and the South Sandwich Islands on the 187th anniversary of the "United Kingdom's illegal occupation". The statement also called for a new round of bilateral negotiations in order to "find a peaceful and definite solution to the dispute". Fernández himself stated that the Malvinas are "a territory [Argentina] will never give up".[123] The Fernández administration gave back secretariat-level status to the Secretariat of Malvinas Affairs, which had been demoted to an undersecretariat during Macri's government.[124]

On 1 March 2020, during the first opening of regular sessions of Congress, Fernández once again stated the government's position on the Falklands matter, and announced three bills to deal with it: the creation of the National Council of Malvinas Affairs, the delimitation of the outer rim of the Argentine continental platform, and the modification of the federal fishing regime to harshen sanctions against illegal fishing in Argentina's claimed maritime zone.[125]

In February 2022, during his state visit to China, Fernández signed an accord with Chinese president Xi Jinping in which China reaffirmed its support to the Argentine claim over the islands, prompting condemnation from the United Kingdom and the local government of the Falklands.[126]

Iran

[edit]Regarding Argentina's strained relations with Iran, Fernández publicly defended the Memorandum of understanding between Argentina and Iran,[127] although critical of this prior to taking office.[128] In September 2020, Fernández asked Iran before the UN General Assembly to "cooperate with the Argentine justice" to bring justice to the cause and extradite those Iranian officials who stand accused of the attack. He further stated that if the officials were to be found innocent, "they could freely return to Iran or otherwise face the consequences for their actions."[127][129]

Mercosur

[edit]During his administration, Argentina's relationship with Brazil has become somewhat strained.[130] Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro refused to attend Fernández's inauguration, accusing him of wanting to create a "great Bolivarian homeland" on the border and of preparing to provoke a flight of capital and companies into Brazil.[131] Fernández and Bolsonaro had their first conversation through a video conference on 30 November 2020, during which both presidents agreed on the importance of cooperation and the role of Mercosur.[132] Despite the two presidents' political differences, trade between Argentina and Brazil grew during the COVID-19 pandemic: according to the Getúlio Vargas Foundation (and based on data provided by the Brazilian economy ministry) Argentina's exports to Brazil grew more than any other countries' between January and November 2021.[133]

The relationship with Uruguay under Fernández and Uruguayan president Luis Lacalle Pou, who was elected on the same day as Fernández, have been described as "tense".[134] Argentina opposes Uruguay's position on the flexibilisation of the Mercosur trade bloc policies, a flagship issue for Lacalle Pou.[135][136] In March 2021, during a Mercosur summit led by Fernández as president pro tempore of the bloc, Lacalle Pou stated that Mercosur "cannot become a burden" for Uruguay, while Fernández responded by saying that if the bloc had become a burden, any of its members were "free to take a different boat".[137]

Russia

[edit]The Fernández administration has maintained friendly ties with Russia under Vladimir Putin. Argentina was the first country in Latin America to greenlight the use of the Russian-developed Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine, and Fernández himself got the Sputnik V vaccine.[138] Argentina was also one of the first countries outside of Russia to produce Sputnik V, with the local Richmond Laboratories providing the necessary infrastructure. [139] Large-scale production started in June 2021.[140][141]

In February 2022, Fernández visited Russia for the first time in his capacity as president, and met with Putin for bilateral talks. Fernández highlighted the friendship between both nations and stated his wish for Argentina to become "Russia's entryway to Latin America".[142]

Argentina did not, however, support Russia during the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Fernández himself lamented the invasion and asked "the Russian Federation to put an end to the military action and return to dialogue".[143] Earlier, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Worship rejected the use of force and called on Russia to respect the charter of the United Nations and international law.[144] Before the UN, Foreign Minister Santiago Cafiero condemned "the invasion of Ukraine as illegitimate and military operations on Ukrainian soil," and said that the world "does not tolerate more deaths or wars".[145]

United States

[edit]

Donald Trump's top adviser for the Western Hemisphere, Mauricio Claver-Carone, crossed Fernández in 2019 saying: "We want to know if Alberto Fernández will be a defender of democracy or an apologist for dictatorships and leaders in the region, whether it be Maduro, Correa or Morales."[146]

Venezuela

[edit]Under Fernández, Argentina has exited the Lima Group, formed by North and South American nations to address the crisis in Venezuela, after not subscribing to any of the Group's statements and resolutions.[147] Argentina voted in favour of the United Nations resolution to back the continuity of the UN Human Rights Office report on human rights violations in Venezuela.[148] Under Fernández, Argentina withdrew recognition of Juan Guaidó as interim President of Venezuela.[149] In January 2020, the Fernández administration revoked the credentials of Guaidó's envoy in Argentina, Elisa Trotta Gamus.[150] However, Fernández also refused to recognise Maduro's envoy Stella Lugo's credentials and Foreign Minister Felipe Solá asked her to return to Caracas.[151][152]

List of international trips and state visits

[edit]| Date(s) | Country | Details | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | |||

| 22–25 January 2020 | State visit. Met with by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. | [153] | |

| 31 January 2020 | State visit. Met with Pope Francis. | [154] | |

| State visit. Met with President Sergio Mattarella and Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte | [155] | ||

| 3 February 2020 | State visit. Met with Chancellor Angela Merkel | [156] | |

| 4 February 2020 | State visit. Met with King Felipe VI and Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez. | [157] | |

| 5 February 2020 | State visit. Met with President Emmanuel Macron. | [158] | |

| 8 November 2020 | Attended the inauguration of President-elect Luis Arce. | [159] | |

| 2021 | |||

| 22–24 February 2021 | State visit. Met with President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. | [160] | |

| 28 July 2021 | Attended the inauguration of President-elect Pedro Castillo. | [161] | |

| 29–31 October 2021 | Attended the 2021 G20 Rome summit. | [162] | |

| 31 October – 11 November 2021 | Attended the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference. | [163] | |

| 2022 | |||

| 2–3 February 2022 | State visit. Met with President Vladimir Putin. | [164] | |

| 3–6 February 2022 | State visit. Met with President Xi Jinping and attended the 2022 Winter Olympics opening ceremony. | [165] | |

| 7–8 February 2022 | State visit. Met with Prime Minister Mia Mottley. | [166] | |

| 11 March 2022 | Attended the inauguration of President-elect Gabriel Boric. | [167] | |

| 10–11 May 2022 | State visit. Met with King Felipe VI and Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez. | [168] | |

| 11–12 May 2022 | State visit. Met with Chancellor Olaf Scholz. | [169] | |

| 12–13 May 2022 | State visit. Met with President Emmanuel Macron. | [170] | |

| 8–10 May 2022 | Attended the 9th Summit of the Americas. | [171] | |

| 26–29 June 2022 | Attended the 48th G7 summit. | [172] | |

| 18-21 September 2022 | Attended the 77th general debate of the UNGA | [173] | |

| 10-12 November 2022 | Attended the fifth edition of the Paris Peace Forum | [174] | |

| 14-16 November 2022 | Attended the 2022 G20 Bali summit | [175] | |

| 18 November 2022 | Working visit. Met with Vice President Yolanda Díaz | [176] | |

| 2023 | |||

| 1-2 January 2023 | Attended the inauguration of President-elect Lula da Silva | [177] | |

| 24-25 March 2023 | Attended the 28th Ibero-American summit | [178] | |

| 27-29 March 2023 | State Visit. Met with President Joe Biden | [179] | |

| 5 April 2023 | Attended the ceremony for the 205th anniversary of the Embrace of Maipú. Met with Gabriel Boric. | [180] | |

| 2 May 2023 | State Visit. Met with President Lula da Silva | [181] | |

| 29-30 May 2023 | Attended the meeting of South American Presidents | [182] | |

| 1 June 2023 | Working Visit. Met with President Luis Arce | [183] | |

| 27 June 2023 | State Visit. Met with President Lula da Silva. | [184] | |

| 17-19 July 2023 | Attended the third EU-CELAC summit. | [185] | |

| 15 August 2023 | Attended the inauguration of President-elect Santiago Peña. | [186] | |

| 8-10 September 2023 | Attended the 2023 G20 New Delhi summit. | [187] | |

| 15-16 September 2023 | Attended the G77+China summit. | [188] | |

| 18-19 September 2023 | Attended the General debate of the 78th UNGA. | [189] | |

| 14-18 October 2023 | Attended the Third Belt and Road Forum. | [190] | |

| 27 October 2023 | Working Visit. Met with President Luis Lacalle Pou and Santiago Peña | [191] | |

| 7 December 2023 | Attended the 63rd Mercosur Heads of State Summit | [192] | |

Controversies

[edit]Fernández has engaged in disputes with users on Twitter before his presidency, in which his reactions have been regarded as aggressive or violent by some.[193][194][195] Tweets show him responding to other users with expletives such as "pelotudo" (Argentinian slang for "asshole"),[196][197] "pajero" ("wanker"),[194][198] and "hijo de puta" ("son of a bitch");[199][200] he also called presidential candidate José Luis Espert "Pajert", a word play between his last name and the Argentine slang for "wanker".[197] In December 2017, he responded to a female user by saying, "Girl, what you think doesn't worry me. You better learn how to cook. Maybe then you can do something right. Thinking is not your strong suit".[201][202]

In June 2020, he told journalist Cristina Pérez to "go read the Constitution", after being questioned about his attempts to install a government-designated administration in the Vicentín agricultural conglomerate.[203]

On 9 June 2021, during a working meeting with business leaders alongside Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez at the Casa Rosada, Fernández sought to play up the Argentinian ties with Europe by saying that "The Mexicans came from the Indians, the Brazilians came from the jungle, but we Argentines came from the ships. And they were ships that came from Europe." Fernández erroneously attributed the quote to the Mexican poet, essayist and diplomat Octavio Paz, although it had originated from lyrics by local musician and personal friend Litto Nebbia. Faced with the negative backlash to his comments, on the same day Fernández apologized on Twitter[204] and the next day sent a letter to the director of the National Institute Against Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism (INADI), clarifying his comments.[205]

In August 2021, it was revealed that there had been numerous visits to the presidential palace during the lockdown that he had imposed in early 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic; visitors included an actress, a dog trainer, and a hairdresser, as well as hosting a birthday party for the First Lady.[206][207]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Tereschuk, Nicolás (28 October 2019). "Perdió Macri". Infobae (in Spanish).

- ^ "Alberto Fernández presidente, Cristina Kirchner vice: el video en el que la senadora anuncia la fórmula". La Nación. 18 May 2019.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández, en su primer acto de campaña: "Salgamos a convocar a todos"". La Nacion (in Spanish). 20 May 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ "Argentina's Massa in line for key Congress role on Fernandez presidential ticket". Reuters. 18 June 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Bullrich, Lucrecia (17 July 2019). "Alberto Fernández recibió el respaldo de la CGT y dijo que no hará reformas" (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ EFE (10 December 2019). "El peronista Alberto Fernández jura el cargo como presidente de Argentina". eldiario.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ "Juraron los ministros del Gabinete de Alberto Fernández". TN (in Spanish). 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "Uno por uno, todos los integrantes del Gabinete". Clarín (in Spanish). 6 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Jastreblansky, Maia (12 November 2020). "Hábitat: sin jurar aún, Jorge Ferraresi ya se pone en funciones y diagrama un cambio de prioridades". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ a b Mayol, Federico (19 February 2021). "Carla Vizzotti, una ministra de confianza del Presidente que tenía una relación quebrada con Ginés González García". Clarín (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ "Asumió Soria. "Losardo hizo exactamente lo que yo le pedí", afirmó Alberto Fernández". La Nación (in Spanish). 29 March 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ "Juan Zabaleta y Jorge Taiana, confirmados como nuevos ministros de Desarrollo y Defensa". Perfil (in Spanish). 9 August 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ "Quién es Juan Manzur, el nuevo jefe de Gabinete de Alberto Fernández". Página/12 (in Spanish). 18 September 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ "Santiago Cafiero seguirá en el Gabinete, pero como ministro". Ámbito (in Spanish). 17 September 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Sergio Massa define los últimos nombres de su equipo antes de asumir como ministro". Ámbito Financiero (in Spanish). 2 August 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández firmó un DNU que establece la doble indemnización por seis meses". Diario La Nación. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Fernández's economic emergency law wins approval in Senate". Buenos Aires Times. 23 December 2019.

- ^ Vinicius Andrade and Jorgelina Do Rosario (24 June 2021). "Argentina Shares Fall After MSCI Cuts Emerging Market Status". Bloomberg. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ "El Gobierno cambió el esquema de retenciones y decidió aumentarlas". Diario La Nación. 15 December 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "Suba de retenciones. Los productores se movilizaron y en algunos lugares ya piden medidas de fuerza". Diario La Nación. 16 December 2019.

- ^ "IMF predicts Argentina's economy will slump 9.9% in 2020". Buenos Aires Time (Perfil). 25 June 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "INDEC: Economy contracted by 5.4% in first quarter of 2020". Buenos Aires Time (Perfil). 23 June 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "IMF predicts deeper global recession due to coronavirus pandemic". Reuters. 24 June 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Informe de avance del nivel de actividad - Segundo trimestre de 2020" [Activity Level Report - Second Quarter 2020] (PDF). Informes técnicos (in Spanish). 4 (172). National Institute of Statistics and Census of Argentina. September 2020. ISSN 2545-6636.

- ^ a b Gillespie, Patrick (22 September 2020). "Argentina's Economy Slumps 16.2%, Narrowly Beating Forecasts". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Pandemic and economic crisis pushes poverty rate up to 42%". Buenos Aires Times. 31 March 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ Goñi, Uki (27 September 2018). "Argentina gets biggest loan in IMF's history at $57bn". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ Grigera, Juan (16 December 2019). "Argentina debt crisis: IMF austerity plan is being derailed". The Conversation. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ Politi, Daniel (22 May 2020). "Argentina Tries to Escape Default as It Misses Bond Payment". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ "Argentina strikes debt agreement after restructuring breakthrough". Financial Times. 4 August 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ "IMF report concludes 2018 loan to Argentina 'did not deliver on its objectives'". Buenos Aires Times. 23 December 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ Geist, Agustín; Misculin, Nicolás; Jourdan, Adam (28 January 2022). "Argentina strikes breakthrough deal with IMF in $45 bln debt talks". Reuters. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ Iñurrieta, Sebastián (1 February 2022). "FMI: Máximo Kirchner renunció a la presidencia del bloque en Diputados en rechazo al acuerdo". El Cronista (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Mander, Benedict (23 March 2020). "Pandemic throws Argentina debt strategy into disarray". Financial Times.

- ^ Do Rosario, Jorgelina; Patrick, Gillespie. "Argentina Orders 'Exceptional' Lockdown in Bid to Stem Virus". Bloomberg. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Squires, Scott; Patrick, Gillespie. "Argentina Says It Aims to Avoid Default Amid Lockdown Extension". Bloomberg. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Costa, José María (9 October 2020). "Covid: las 18 provincias que tendrán aislamientos de 14 días en algunas zonas". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Argentina to close borders for non-residents to combat coronavirus". Reuters. 15 March 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ a b Mander, Benedict. "Pandemic throws Argentina debt strategy into disarray". Financial Times. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Rapoza, Kenneth. "Argentina Goes Under Quarantine As Debt Deal Now An Afterthought". Forbes. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Meakin, Lucy (20 March 2020). "Cash and Low Rates: How G-20 Policy-Makers Are Stepping Up". National Post. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Newbery, Charles. "Argentina unveils $11 bln stimulus package". LatinFinance. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus en Argentina: será obligatoria la cuarentena para quienes regresen de los países más afectados". Clarín (in Spanish). 11 March 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "Cuarentena por coronavirus: cuáles son los países de riesgo para los viajeros que vuelven a la Argentina". Clarín (in Spanish). 9 March 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "El Gobierno cierra fronteras, aeropuertos y puertos por el coronavirus: la veda alcanza a los argentinos". Clarín (in Spanish). 26 March 2020.

- ^ Ruiz, Iván; Arambillet, Delfina (24 April 2020). "Coronavirus en la Argentina: pocas donaciones, muchas compras y el inicio de un malestar con China". La Nación (in Spanish).

- ^ "Coronavirus: el Gobierno le pide ayuda a China para conseguir más respiradores". La Nación (in Spanish). 23 March 2020.

- ^ "Por qué Alberto Fernández no debería saludar con un abrazo". Chequeado (in Spanish).

- ^ "Son verdaderas las fotos de Alberto Fernández sin barbijo y sin distanciamiento social". Chequeado (in Spanish).

- ^ "Una foto "borrada" de Alberto, Moyano y Fabiola sin barbijo ni distancia generó revuelo". Perfil.com (in Spanish).

- ^ "Coronavirus. "Seguimos hablando de cuarentena sin que en la Argentina existan cuarentenas" y otras frases de Alberto Fernández". La Nación (in Spanish).

- ^ "Alberto Fernandez: "Estuve en la calle manejando y vi que la gente en CABA sale y camina"". Infobae (in Spanish).

- ^ Jastreblansky, Maia (6 November 2020). "Alberto Fernández, Rodríguez Larreta y Kicillof confirmaron que el AMBA deja atrás la fase de "aislamiento"". La Nación (in Latin American Spanish).

- ^ "El AMBA pasa a una etapa de distanciamiento social hasta el 29 de noviembre". Ámbito Financiero (in Latin American Spanish). 6 November 2020.

- ^ "Por la cuarentena, la actividad se derrumbó casi 10% en marzo según Ferreres". Ámbito Financiero (in Spanish). 24 April 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "El déficit fiscal primario trepó 857% en marzo por paquete "anticoronavirus" y caída en la actividad". Ámbito Financiero (in Spanish). 20 April 2020.

- ^ Maximiliano Fernandez (2 October 2020). "Estiman que al menos 1.5 millones de alumnos abandonarán la escuela después de la cuarentena" [It is estimated that 1.5 millions of students will drop school after the quarantine] (in Spanish). Infobae. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ "En medio de la cuarentena total, hoy abren los bancos: quiénes pueden ir y cómo van a funcionar". Infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Raszewski, Eliana; Lobianco, Miguel (3 April 2020). "'Ridiculous' block-long lines at banks greet Argentine pensioners, at high risk for coronavirus". Reuters. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Doll, Ignacio Olivera. "Argentines disobey virus lockdown to collect money from banks". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Indignados y enojados: testimonios de jubilados que sufrieron el desborde de los bancos". Infobae (in European Spanish). Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ González, Enric (3 April 2020). "Miles de jubilados se agolpan ante los bancos argentinos y se exponen a un contagio masivo". El Pais (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus en Argentina: Por el caos en el pago a jubilados, la oposición pide que Alberto Fernández "separe" a los responsables". Clarin (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Argentina's president sits for Russian Covid jab". France 24. 21 January 2021.

- ^ Centenera, Mar (21 January 2021). "Alberto Fernández, primer presidente de América Latina en vacunarse contra la covid-19". El País (in Spanish).

- ^ Parra Roa, Daniel (7 December 2021). "Presidente de Argentina recibe la dosis de refuerzo contra el Covid-19" [President of Argentina receives the booster dose against Covid-19]. Radio Agricultura Chile (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "Argentina's health minister forced to resign amid COVID vaccine scandal after his ineptitude as a health minister". Euro News. 19 February 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ Mathieu, Edouard; Ritchie, Hannah; Rodés-Guirao, Lucas; Appel, Cameron; Giattino, Charlie; Hasell, Joe; MacDonald, Bobbie; Dattani, Saloni; Beltekian, Diana; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban; Roser, Max (5 March 2020). "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations - Statistics and Research - Our World in Data". Our World in Data.

- ^ "Argentine health minister resigns amid vaccine scandal". AP NEWS. 19 February 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "Argentine leader Alberto Fernandez says tests positive for coronavirus". Reuters. 2 April 2021.

- ^ Chávez, Valeria (23 January 2022). "Cuál es el estatus de vacunación de la población argentina en plena tercera ola". Infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "El Gobierno anunció la aplicación de una tercera dosis de vacuna covid-19 para inmunocomprometidos y para mayores de 50 años con sinopharm". argentina.gob.ar (in Spanish). 26 October 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "El Gobierno promulgó la ley de Emergencia Alimentaria Nacional". Télam (in Spanish). 30 September 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "El plan de Alberto Fernández contra el hambre". Página 12 (in Spanish). 7 October 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Mercado, Silvia (20 December 2019). "El Gobierno puso en marcha su proyecto más ambicioso: el Consejo Argentina contra el Hambre". Infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Torino, Martín (15 December 2019). "El Gobierno lanza y entrega esta semana la primera tanda de tarjeta de alimentos". El Cronista (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "'Argentina Contra el Hambre', cómo es el programa que Alberto Fernández implementará ni bien asuma". El Cronista (in Spanish). 15 November 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "Bono del IFE, ATP y créditos a tasa cero: tres gráficos que muestran el impacto en cada provincia". BAE Negocios (in Spanish). 6 June 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "El Gobierno oficializó la prórroga de la prohibición de despidos hasta el próximo 31 de diciembre". argentina.gob.ar (in Spanish). 28 June 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Timerman, Jordana (3 February 2020). "Can Argentina's Feminists Change Government?". Americas Quarterly. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández confirmó que enviará en 2020 el proyecto para legalizar el aborto". Infobae.com. 31 December 2019.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández, sobre la legalización del aborto: "Ahora tengo otras urgencias"". Clarin.com. 2 June 2020.

- ^ Carbajal, Mariana (10 November 2020). "Aborto legal: el Gobierno enviará el proyecto al Congreso durante noviembre". Página/12 (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ Carbajal, Mariana (17 November 2020). "Aborto legal: Alberto Fernández enviará hoy el proyecto al Congreso". Página/12 (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ Goñi, Uki; Phillips, Tom (30 December 2020). "Argentina legalises abortion in landmark moment for women's rights: Country becomes only the third in South America to permit elective abortions". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ "El presidente argentino firma el decreto para promulgar la ley del aborto". Swissinfo (in Spanish). 14 January 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Carrasco, Adriana (3 January 2020). "Quién es Alba Rueda, la primera subsecretaria de Políticas de Diversidad de la Nación". Soy. Página/12 (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ "Por decreto, el Gobierno estableció un cupo laboral para travestis, transexuales y transgénero". Infobae (in Spanish). 4 September 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "El Gobierno decretó el cupo laboral trans en el sector público nacional". La Nación (in Spanish). 4 September 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "Decreto 476/2021". Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina (in Spanish). 20 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández pondrá en marcha el DNI para personas no binarias". Ámbito (in Spanish). 20 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Identidad de género: el Gobierno emitirá un DNI para personas no binarias". La Nación (in Spanish). 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Quién es Sabina Frederic, la ministra de Seguridad de Alberto Fernández". El Cronista (in Spanish). 27 December 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Argentina derogó el protocolo de detención de personas LGBT". 20minutos.com.mx (in Spanish). 9 March 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "El Ministerio de Seguridad derogó normativas sobre el uso de armas por parte de las fuerzas federales". Infobae (in Spanish). 24 December 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Giro en Seguridad: el Gobierno derogará el protocolo de uso de armas de fuego y el control de DNI en trenes". La Nación (in Spanish). 16 December 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Ybarra, Gustavo (8 April 2020). "Sabina Frederic reveló que las fuerzas de seguridad realizan "ciberpatrullajes" en las redes sociales para medir el humor social". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Frederic habló de "ciberpatrullaje para medir humor social" y desató otra polémica". Perfil (in Spanish). 8 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Sabina Frederic dio marcha atrás y reconoció que su frase sobre el ciberpatrullaje en redes fue poco feliz". Infobae (in Spanish). 9 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Los ejes del discurso de Alberto Fernández: la deuda, la reforma de la Justicia, la AFI y anuncios económicos". La Nación (in Spanish). 10 December 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Cappiello, Hernán (21 December 2019). "Espías. Confirman a Cristina Caamaño como interventora de la AFI". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "AFI: Alberto Fernández firmará un DNU para limitar las facultades de los espías". La Nación (in Spanish). 1 March 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Hasse, Javier (12 November 2020). "Argentina Regulates Medical Cannabis Self-Cultivation, Sales, Subsidized Access". Forbes. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández, sobre el consumo de marihuana: "No tenemos que perseguir a los fumadores de porro"". La Nación (in Spanish). 18 June 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "Death toll from laced cocaine in Argentina climbs to 23". France 24. 4 February 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ Goñi, Uki (3 February 2022). "Argentinians urged to throw out cocaine after tainted batches kill at least 23". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "Argentina drugs: Adulterated cocaine kills 20 in Buenos Aires". BBC. 3 February 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ Lejtman, Román (24 January 2020). "Alberto Fernández, a Netanyahu: "Nuestro compromiso por saber la verdad de lo que pasó en la AMIA es absoluto"". Infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ "Benjamin Netanyahu felicitó a Alberto Fernández por mantener la postura contra Hezbollah". Perfíl (in Spanish). 24 January 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ Rosemberg, Jaime; Lacour, Pedro (7 January 2022). "El presidente Alberto Fernández asumió la presidencia de la Celac, con el acompañamiento de Nicaragua". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "El presidente argentino aboga por una Celac de "consenso" y sin "exclusiones"". EFE (in Spanish). 7 January 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández defendió la legitimidad de la reelección de Evo Morales en Bolivia". Diario La Nación. 29 February 2020.

- ^ "Evo Morales granted refugee status in Argentina". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández acompañó a Evo Morales hasta la frontera con Bolivia y dejó un mensaje". La Nación (in Spanish). 9 November 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Arce y Fernández hablan sobre la 'importancia de concluir las negociones de la sexta adenda' al contrato de gas". Los Tiempos (in Spanish). Cochabamba. 11 March 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ Diamante, Sofía (7 April 2022). "Acuerdo con Bolivia por el gas: la Argentina dependerá de Brasil y pagará un precio 'de emergencia'". La Nación (in Spanish). Buenos Aires. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Argentina joins China's Belt and Road initiative, eyes US$23 billion investment". Buenos Aires Times. 6 February 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "Vaca Narvaja destacó el "apoyo contundente" de China a la postura argentina ante el FMI". Télam (in Spanish). 7 February 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ Jourdan, Adam; Simao, Paul (1 February 2022). "Argentina's Fernandez set for China, Russia tour after IMF accord". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández plantea a Argentina como la "puerta de entrada" de Rusia en América Latina". France 24 (in Spanish). 3 February 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández en Barbados, última escala de su gira". Página 12 (in Spanish). 8 February 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "Argentina y China firman contrato para construir una central nuclear". Deutsche Welle (in Spanish). 1 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ ""Las Malvinas son una tierra a la que nunca vamos a renunciar"". Crónica (in Spanish). 3 January 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "Filmus officially appointed as Malvinas, Antarctica and South Atlantic Secretary". MercoPress (in Spanish). 30 December 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández en el Congreso: los tres proyectos sobre las islas Malvinas". La Nación (in Spanish). 1 March 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "Truss says Falklands part of 'British family' after China backs Argentina". The Guardian (in Spanish). 7 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ a b Niebieskikwiat, Natasha (16 July 2020). "Alberto Fernández defendió el Memorándum con Irán por la Causa AMIA" [Alberto Fernández defended the Memorandum with Iran for the AMIA Cause]. Clarín (in Spanish).

- ^ Cappiello, Hernán (16 July 2020). "El giro de Alberto Fernández: qué decía antes y qué dice hoy de Cristina Kirchner y el memorándum con Irán" [Alberto Fernández's turn: what he said before and what he says today about Cristina Kirchner and the memorandum with Iran]. La Nación (in Spanish).

- ^ "Alberto Fernández en la ONU: "Le pido a Irán que coopere con la justicia argentina para avanzar en la investigación del atentado a la AMIA"" [Alberto Fernández at the UN: "I ask Iran to cooperate with the Argentine justice to advance the investigation of the AMIA attack"]. Infobae (in Spanish). 22 September 2020.

- ^ Ochoa, Raúl (17 February 2020). "Argentina-Brasil: incierto escenario para una relación indispensable". Clarín (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Jair Bolsonaro: "Quiero una Argentina fuerte, no una patria bolivariana"". Infobae (in Spanish). 13 February 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Niebieskikwiat, Natasha (30 November 2020). "Alberto Fernández mantuvo su primera conversación con Jair Bolsonaro: "La única diferencia que tenemos es en el fútbol"". Clarín (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Menegazzi, Eduardo (17 December 2021). "Mercosur: Alberto Fernández participará de una Cumbre en la que intentará que Uruguay no introduzca cambios". Infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "Frialdad argentina y las diferencias que marcan distancia con Uruguay". El Economista (in Spanish). 5 March 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "En medio de la tensión por el Mercosur, Alberto Fernández recibió a Luis Lacalle Pou". Ámbito Financiero (in Spanish). 13 August 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "Lacalle Pou dio detalles de un posible tratado de libre comercio con China". elDiario.ar (in Spanish). 7 September 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "Tensión en el Mercosur: "Si somos un lastre, que tomen otro barco", dijo el Presidente". elDiario.ar (in Spanish). 26 March 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "Belarus registers Sputnik V vaccine, in first outside Russia – RDIF". Reuters. 21 December 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ "In Latin American first, Argentina to produce Russia's Sputnik V vaccine". France 24. 20 April 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Laboratorios Richmond set to begin manufacturing Sputnik V second doses". Buenos Aires Times. 30 June 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Sputnik V: empieza la producción del componente 2 en la Argentina". Página/12 (in Spanish). 29 June 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández quiere que Argentina sea una "puerta de entrada" de Rusia a América Latina". Deutsche Welle (in Spanish). 3 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández le pidió a Rusia que cese el ataque y que respete la soberanía" [Alberto Fernández asked Russia to stop the attack and to respect sovereignty]. La Nación (in Spanish). 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "Ataques a Ucrania: Argentina reclamó que Rusia cese las acciones militares" [Attacks on Ukraine: Argentina demanded that Russia cease military actions]. La Voz (in Spanish). 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "Santiago Cafiero, ante la ONU: "La Argentina condena la invasión a Ucrania"" [Santiago Cafiero, before the UN: "Argentina condemns the invasion of Ukraine"]. La Nación (in Spanish). 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Clarín.com (14 December 2019). "Durísimo mensaje de EE.UU contra Alberto F: "Queremos saber si va a ser abogado de la democracia o apologista de las dictaduras"". www.clarin.com (in Spanish).

- ^ Dinatale, Martín (13 October 2020). "La Argentina permanecerá en el Grupo Lima pero rechazará una declaración contra Venezuela". Infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Argentina votó a favor del informe de Bachelet y volvió a condenar el bloqueo a Venezuela". Télam (in Spanish). 6 October 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Foreign Ministry withdraws 'special' status granted to Guaidó's envoy". Buenos Aires Times. 7 January 2020.

- ^ "El Gobierno le quitó las credenciales a Elisa Trotta, la embajadora de Juan Guaidó en Argentina" [The Government revoked the credentials of Elisa Trotta, Juan Guaidó's ambassador in Argentina]. Clarín. 7 January 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández rechaza a Stella Lugo como embajadora de Maduro en Argentina" [Alberto Fernández rejects Stella Lugo as Maduro's ambassador in Argentina]. Diario Las Americas (in Spanish). 13 January 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández rechazó a Stella Lugo como embajadora de Maduro en Argentina" [Alberto Fernández rejected Stella Lugo as Maduro's ambassador in Argentina]. El Nacional (in Spanish). 13 January 2020.

- ^ Carelli Lynch, Carelli (25 January 2020). "Alberto Fernández culminó su visita a Israel y ratificó su "compromiso" para saber la verdad sobre el atentado a la AMIA". Clarín (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ Sued, Gabriel (31 January 2020). "Bromas y buen clima: el papa Francisco y Alberto Fernández se reunieron durante 44 minutos en el Vaticano". La Nación (in Spanish).

- ^ "Alberto Fernández aseguró que Italia se comprometió a apoyar a la Argentina en su renegociación de la deuda". Infobae (in Spanish). 31 January 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ Sued, Gabriel (3 February 2020). "Angela Merkel sobre la crisis argentina: "Es importante pensar cómo podemos ayudarlos"". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ Ventura, Laura (4 February 2020). "Fernández se reunió con Sánchez en Madrid y dijo que consiguió su respaldo ante el FMI". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ Sued, Gabriel (5 February 2020). "Alberto Fernández cerró la gira europea con la promesa de Emmanuel Macron de interceder ante el Fondo". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández participó de la asunción de Luis Arce: "Se termina la pesadilla, Bolivia recupera la democracia"". Ámbito (in Spanish). 8 November 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández llega en visita oficial a México". Deutsche Welle (in Spanish). 22 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández asiste en Perú a la asunción de Pedro Castillo". Télam (in Spanish). 28 July 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "El Presidente ya llegó a Roma donde participará de la Cumbre de Líderes del G20". casarosada.gob.ar (in Spanish). 29 October 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández: "La justicia social ambiental es el nuevo nombre del desarrollo"". casarosada.gob.ar (in Spanish). 8 November 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández: "Estamos dando un paso importante para que la Argentina y Rusia profundicen sus lazos"". casarosada.gob.ar (in Spanish). 3 February 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "El presidente Alberto Fernández se reunió con Xi Jinping en el Gran Palacio del Pueblo y acordaron la incorporación de la Argentina a la Franja y la Ruta de la Seda". casarosada.gob.ar (in Spanish). 6 February 2022.

- ^ "El presidente se reunió con la primera ministra de Barbados para profundizar en la agenda por el cambio climático". casarosada.gob.ar (in Spanish). 8 February 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "El presidente arribó a Chile para participar de la ceremonia de traspaso de mando a Gabriel Boric Font". casarosada.gob.ar (in Spanish). 11 March 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ "El presidente se reunió con el Rey Felipe VI de España". casarosada.gob.ar (in Spanish). 10 May 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "El presidente llegó a Berlín donde se reunirá con el canciller Federal de Alemania, Olaf Scholz". casarosada.gob.ar (in Spanish). 11 May 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "El presidente Alberto Fernández mantuvo un encuentro bilateral con su par de Francia, Emmanuel Macron". casarosada.gob.ar (in Spanish). 13 May 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ "El presidente concluyó su agenda de trabajo en la IX Cumbre de las Américas". casarosada.gob.ar (in Spanish). 10 June 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "El presidente finalizó su participación en la Cumbre del G7". casarosada.gob.ar (in Spanish). 27 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández: "Pudimos traer la mirada del Gobierno a las Naciones Unidas sobre cómo vemos el presente de Argentina y del mundo"". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández: "Macron me ha acompañado en esta lucha de hacer una América Latina más integrada al mundo"". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "El presidente se reunió con Kristalina Georgieva en Bali". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "El presidente se reunió con la vicepresidenta de España Yolanda Díaz". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández: "Hemos decidido volver a poner en marcha el vínculo entre Argentina y Brasil con toda la fuerza que siempre debió tener"". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández: "Si queremos una Iberoamérica justa y sostenible, el primer paso que debemos dar es restablecer la unidad"". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández: "Estoy convencido de que se han abierto las puertas para un trabajo estratégico y en conjunto con los Estados Unidos"". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ "Los presidentes Alberto Fernández y Gabriel Boric reafirmaron la importancia de la relación estratégica entre Argentina y Chile". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández: "Celebro el apoyo explícito que el presidente Lula nos ha dado como país y como gobierno"". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ "Los presidentes de América del Sur alcanzaron un consenso de cooperación e integración de la región". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ "Fernández y Arce inauguraron un electroducto que permitirá mejorar el abastecimiento de energía eléctrica". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ "El presidente se reunió con representantes del Poder Legislativo y Judicial de Brasil". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "El presidente Alberto Fernández se reunió con diputados y diputadas del Parlamento Europeo". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández participó de la ceremonia de asunción del presidente de Paraguay". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "El presidente se reunió con el primer ministro de Arabia Saudita y el canciller federal de Alemania, Olaf Scholz". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "El presidente se reunió con su par de Cuba, Miguel Díaz-Canel". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández: "El sistema financiero internacional busca imponer políticas que profundizaron la desigualdad"". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández anunció la ampliación del swap con China por 6.500 millones de dólares". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "El presidente se reunió con sus pares de Uruguay y Paraguay para definir la organización de los partidos inaugurales del Mundial Centenario 2030". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ ""Todos tenemos la misma voluntad de hacer fuerte al Mercosur", dijo el presidente en Brasil". Casa Rosada (in European Spanish). Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ Fontevecchia, Agustino (7 December 2019). "Alberto, Cristina and a distaste for institutions". Buenos Aires Times.

- ^ a b "Alberto Fernández en Twitter: Respuestas feroces y mensajes desbocados de un tuitero que no se queda en el molde" [Alberto Fernández on Twitter: Fierce responses and uncontrolled messages from a tweeter who does not hold back]. Diario Popular (in Spanish).

- ^ "El video que expone lo peor de Alberto: sus agresiones "épicas" son virales" [The video that exposes Alberto's worst: his "epic" attacks are viral]. infotechnology.com (in Spanish).

- ^ @alferdez (19 March 2019). "Que pedazo de pelotudo resultaste. Pasaste de hacerme reír a tener pena por tu imbecilidad. Solo agradece que mi paciencia es infinita. Y rogá que tus imbéciles prepoteadas un día no se crucen con alguien sanguíneo. Seguí tu vida. Pelotudo."" [What an asshole you turned out to be. You went from making me laugh to being sorry for your stupidity. Just be thankful that my patience is infinite. And pray that one day your prepotent idiocies don't cross paths with someone with blood. Go on with your life. Asshole."] (Tweet) (in Spanish) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b "Los insultos de Alberto Fernández a los usuarios en las redes sociales" [Alberto Fernandez's insults to social media users]. La Nación (in Spanish). 20 May 2019.

- ^ @alferdez (6 April 2019). "Pajero y pelotudo... lo tuyo no tiene cura. Y no te insulto. Te describo" [Wanker and asshole... your thing has no cure. And I don't insult you. I describe you.] (Tweet) (in Spanish) – via Twitter.

- ^ @alferdez (26 March 2019). "Andamos muy bien, pedazo de hijo de puta" [We're doing fine, you son of a bitch] (Tweet) (in Spanish) – via Twitter.

- ^ "El año de Alberto en Twitter: insultos, gifs graciosos y guiños para la unidad anti Macri" [A year of Alberto on Twitter: swearing, funny gifs and winks towards an anti-Macri ensemble]. A24 (in Spanish). 8 November 2019.

- ^ @alferdez (11 December 2017). "Nena, no es algo que me inquiete lo que vos creas. Mejor aprende a cocinar. Tal vez así logres hacer algo bien. Pensar no es tu fuerte. Está visto" [Girl, what you think doesn't worry me. You better learn how to cook. Maybe then you can do something right. Thinking is not your strong suit. It's seen.] (Tweet) (in Spanish) – via Twitter.

- ^ ""Mejor aprende a cocinar": Usuarios reviven polémicos tuits del nuevo presidente de Argentina" ["You better learn how to cook": Users revive new Argentine president's polemic tweets]. Radio Programas del Perú (in Spanish). 28 October 2019.

- ^ "El tenso cruce entre Alberto Fernández y Cristina Pérez durante una entrevista" [The tense crossing between Alberto Fernández and Cristina Pérez during an interview]. Infobae (in Spanish).

- ^ "Uproar after Argentina president says 'Brazilians came from the jungle'". The Guardian. Reuters. 9 June 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández le envió una carta al INADI con su posición sobre la población argentina y latinoamericana". Página/12 (in Spanish). 11 June 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Portes, Ignacio (26 August 2021). "Argentina's president tries to contain fallout from lockdown party photos". Financial Times.

- ^ "La fiscalía pidió medidas y avanza la causa por las visitas a la quinta de Olivos durante la cuarentena". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 August 2021.

External links

[edit]- Official website (in Spanish)