Ronald L. Haeberle

Ronald L. Haeberle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1941 |

| Occupation | U.S. Army photographer |

| Years active | 1966 - 1968 |

| Known for | Photographs taken at the scene of the Mỹ Lai Massacre |

| Title | Sergeant (SGT), Information Office, 11th Infantry Brigade (31st Public Information Detachment)[1]: p.770 |

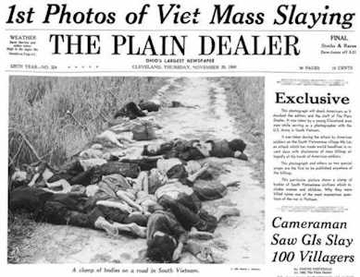

Ronald L. Haeberle (born c. 1941) is a former United States Army combat photographer best known for the photographs he took of the My Lai Massacre on March 16, 1968. The photographs were definitive evidence of a massacre, making it impossible for the U.S. Army or government to ignore or cover up.[2] On November 21, 1969, the day after the photographs were first published in Haeberle's hometown newspaper, The Cleveland Plain Dealer, Melvin Laird, the Secretary of Defense, discussed them with Henry Kissinger who was at the time National Security Advisor to President Richard Nixon. Laird was recorded as saying that while he would like "to sweep it under the rug," the photographs prevented it.[3][4][5]

At the time of the massacre, Haeberle was a sergeant assigned as public information photographer to Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment. With him were three cameras: two Army issued black and white cameras for official photos and his own personal camera containing color slide film.[6] It was the color photographs he took that day that provided evidence of the massacre and elevated the story of My Lai to world-wide prominence.[7] A year after Haeberle returned to his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio with an honorable discharge, he offered them to The Cleveland Plain Dealer, which published a number of them along with his personal account on November 20, 1969.[8] He then sold the photos to LIFE magazine, which published them in the December 5, 1969, issue.[7]

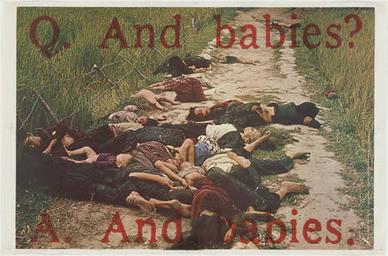

One of Haeberle's photos became an iconic symbol of the massacre, in large part because of its use in the And babies poster, which was distributed around the world, reproduced in newspapers, and used in protest marches.[9] Even though there were many other massacres by U.S. forces during the war, this image and Mỹ Lai itself came to represent them all.[10][11]

Background

[edit]Haeberle was born and raised in a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio. In high school he played football and ran track, graduating in the spring of 1960. In 1962, he began attending Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, where he majored in photography.[12]

During his senior year in 1966 he reduced his classes to part-time not realizing this made him eligible for the draft. At that time the U.S. military was drafting large numbers of young men to expand the war in Vietnam. In fact, 1966 was the high water mark for the number of men who were inducted into the military through the Selective Service System, with over 380,000 drafted that year.[13] He requested a delay to finish his degree, but was denied. In April 1966, he was sent to Fort Benning (now Fort Moore), Georgia, for Army Basic Training.[12]

After basic training, he was trained as a mortarman and was then given orders to report to the 11th Infantry Brigade at Schofield Barracks in Honolulu, Hawaii. When the brigade commander found out he had majored in photography, he was reassigned to a newly formed public information office for the brigade. Here he took pictures of training exercises, award ceremonies and other facets of daily Army life which were published in the brigade newsletter. He also sent official photos and news releases about the brigade's soldiers to hometown newspapers. In late 1967 his brigade was sent to Vietnam. Haeberle only had a little over four months left on his two year draft obligation, and could have stayed in Hawaii, but volunteered to go to Vietnam with the brigade.[12] While in Vietnam, he continued his public information duties recording routine official events - all that was about to change.[14]

Years later Haeberle recalled that his unit received only a one hour briefing on the people and situation in Vietnam. It focused on the dangers they would face and warned of Viet Cong (VC) guerillas and booby traps. Viet Cong was the pejorative name used by the South Vietnamese and American GIs for the military arm of the National Front for the Liberation of the South (NLF).[15] He recalled nothing being said about how to interact with the Vietnamese people, the people they were supposedly helping.[12] In fact, as Time magazine described it quoting him:

"'We were told, "Life is meaningless to these people,"' he said, leaving unspoken the rest of that sentiment: The enemy is not like us. They’re not quite human."[2]

On March 15, 1968, he was briefed about Charlie Company's planned operation the next day in the area near a small hamlet called Mỹ Lai. As a "short-timer" with just over a week to go, he could have opted out of the mission, but again volunteered to go. Early the next morning a helicopter dropped him and his three cameras into some rice paddies near a village.[8] He had no idea anything unusual would be happening that day - a day that was later called "the most shocking episode of the Vietnam War".[16][17]

Eleven days later, Haeberle left Vietnam for the United States and life as a civilian. With him were his undeveloped color photos of the Mỹ Lai Massacre.[12]

Mỹ Lai massacre

[edit]

On November 20, 1969, when The Plain Dealer published his color photos and eye-witness account of what he had seen, the public in the United States and around the world was able to see and learn the shocking details of the massacre for the first time.[18]

Mỹ Lai was actually the name of only one of two hamlets in the village of Sơn Mỹ in Quảng Ngãi Province.[19] Currently, the event is referred to as the Mỹ Lai Massacre in the United States and the Sơn Mỹ Massacre in Vietnam (see Sơn Mỹ Memorial).[20] The U.S. military was aggressively trying to regain the initiative in South Vietnam after the January 1968 Vietnamese Tet Offensive. U.S. military intelligence was under the impression that a NLF Battalion had taken refuge in Sơn Mỹ. Charlie Company was sent to the village with orders to burn the houses, kill the livestock, destroy food supplies, and destroy and/or poison the wells.[21] Soldiers testified that their orders, as they understood them, were to kill all VC combatants and "suspects", including women and children, as well as all animals.[22] When Charlie Company was briefed the night before, their commanding officer, Captain Ernest Medina was asked "Are we supposed to kill women and children?" Medina's reply was, "Kill everything that moves."[23]

Haeberle's photos

[edit]When Haeberle arrived in the area by helicopter he began moving forward with Charlie Company and was soon witnessing scenes he has "never been able to forget". He told The Plain Dealer that "He couldn't stand what was going on". He personally witnessed U.S. soldiers mechanically kill as many as 100 Vietnamese civilians, "many of them women and babies, many left in lifeless clumps."[8] The photos he took provided "horrifying images of piled dead bodies and frightened Vietnamese villagers."[24] In all, a little over 500 unarmed people were killed, including men, women, children, and infants. Some of the women were gang-raped and their bodies mutilated, and some soldiers mutilated and raped children who were as young as 10.[25][26][27]

He partially recorded one of these incidents in one of his most dramatic photographs, which was taken just before the women and children in the photo were killed.

As Haeberle described it to The Plain Dealer:

The GIs found a group of people—mothers, children, and their daughters. This GI grabbed one of the girls...and started stripping her, playing around. They said they wanted to see what she was made of and stuff like that.

I remember they were keeping the mother away from protecting her daughter—she must have been around 13—by kicking the mother in the rear and slapping her around.

.... They were pleading for their lives. The looks on their faces, the mothers were crying, they were trembling.

I turned my back because I couldn't look. They opened up with two M16's. On automatic fire...35, 40 shots.

I couldn't take a picture of it, it was too much. One minute you see people alive and the next minute they're dead.[8]

When he testified before Congress in April 1970 he added additional information about what he had seen:

More or less tormenting these people, especially that woman in front. They were grabbing her, and kicking her around. And I believe it to be the girl behind her that they were trying to rip off her blouse, but I don't believe they succeeded. Sort of fondling her, yelling "VC," "Boom, boom," and that....which means Vietnamese whore. I remember them kicking the old woman right in the ass. She was down on the ground a couple of times, slapping her around.... I just started to turn to walk away to the outside of the village, well, all of a sudden I heard fire, out of the corner of my eyes I could see the people dropping, which started to make me sick.[1]: p.502

The Army Journalist, Specialist 5th Class Jay Roberts, who was with Haeberle that day, recalled the same scene and "stated that the older woman, who he presumed to be the girl’s mother, had been 'biting and kicking and scratching and fighting off' the group of soldiers."[28]

Perhaps Time magazine described the impact of this photo best: "Haeberle’s picture of terror and distress on these faces, young and old, in the midst of slaughter remains one of the 20th century’s most powerful photographs. When the Plain Dealer (and later, LIFE magazine) published it, along with a half-dozen others, the images graphically undercut much of what the U.S. had been claiming for years about the conduct and aims of the conflict. Anti-war protesters needed no persuading, but 'average' Americans were suddenly asking, What are we doing in Vietnam?"[2] On December 5, 1969, Walter Cronkite, on the CBS Evening News, issued a warning about disturbing images Haeberle's photos were broadcast. According to PBS, "The horrific images immediately cause a country-wide uproar."[29]

Other photos

[edit]- In the first photo, an American soldier adds fuel to a fire under orders to burn down houses. He is using baskets the Vietnamese used to dry rice and roots.[21][7]

- A man and two children who were killed despite soldiers being told they were not part of the Viet Cong.[2]

- A woman shot in the head by U.S. soldiers. In 2011, Haeberle learned that this woman was the mother of three My Lai survivors who he got to know (see below for more).[30]

Some photos destroyed

[edit]Years later, Haeberle admitted that he had destroyed a few of photographs he took during the massacre. Unlike the photographs of the dead bodies, the destroyed photographs depicted American soldiers in the process of murdering Vietnamese civilians.[31] "I destroyed two images. They were of a couple of GIs, where you could identify them doing the killing. I figured, why should I implicate them—we're all guilty—there were one hundred-plus of us there."[32]

Haeberle's eyewitness account

[edit]Haeberle's verbal account to The Plain Dealer were almost as searing as his photos.

There were some South Vietnamese people, maybe 15 of them, women and children included; walking on a dirt road maybe 100 yards away. All of a sudden the GIs just opened up with M16's. Besides the M16 fire, they were shooting at the people with M79 grenade launchers. I couldn't believe what I was seeing.

Off to the right, I noticed a woman appeared from some cover and this one GI fired first at her, then they all started shooting at her, aiming at her head. The bones were flying in the air chip by chip. I'd never seen American shoot civilians like that.

There was no reaction on the guy doing the shooting. That's the part that really got me—this little girl pleading and they were just cut down.

.... Off to the left, a group of people—women, children, and babies.... and all of a sudden I heard this fire... [and he] had opened up on all these people in the big circle, and they were trying to run. I don't know how many got out.

There were two small children, a very young boy and a smaller boy, maybe 4 or 5 years old. A guy with an M16 fired at them, at the first boy, and the older boy fell over to protect the smaller boy. The GI fired some more shots with a tracer and the tip somehow seemed to be still burning the boy's flesh. Then they fired six more shots and just let them lie.

I came up to a clump of bodies and I saw this small child. Part of his foot had been shot off, and he went up to this pile of bodies and just looked at it, like he was looking for somebody. A GI knelt down beside me and shot the little kid. His body flew backwards into the pile.

I had emotional feelings. I felt nauseated to see people treated this way. American GIs were supposed to be protecting people and rehabilitating them and I had seen that. But this was incredible. I watched it and it wouldn't sink in.

I left the village around 11 o'clock that morning. I saw clumps of bodies, and I must have seen as many as a hundred killed. It was done very businesslike.[8]

During his Congressional testimony he described additional incidents he had witnessed:

...there was a small child that came walking toward me. He was wounded in the leg.... he was by himself. I just wanted to take a photograph of this child, you know, just wounded, maybe going to get medical help. I don't know, so I was getting ready to focus on him, and all of a sudden the GI just shot him. He put three slugs into him. I can remember, this is so vivid it is hard to forget. First shot him in the stomach, second shot lifted him up, third shot put him down on the ground and all the body fluid just came out from underneath him. This was done by an American GI because I remember him getting up and just looked him in the face, and he had the coldest, hardest look. And just walked away.[1]: pp.503–4

In an interview years later, Haeberle commented:

I knew it was something that shouldn't be happening but yet I was part of it. I think I was in a kind of daze from seeing all these shooting and not seeing any return fire. Yet the killings kept going on. The Americans were rounding up the people and shooting them, not taking any prisoners. It was completely different to my concept of what war is all about." "I felt I wanted to do something to stop this.... I asked some soldiers: "Why?" They more or less shrugged their shoulders and kept on with the killing."[33]: pp.124&133

"No Viet Cong"

[edit]The official Army press dispatch on the operation said the VC body count was 128 and there was no mention of civilian casualties. "US TROOPS SURROUND REDS, KILL 128," was the headline in the American military newspaper Stars and Stripes.[34][33]: p.182 Haeberle told The Plain Dealer, "There were no Viet Cong... they were just poor, innocent illiterate peasants."[8] He reiterated this before Congress when Congressman William L. Dickinson asked him if he ever heard anything that he could identify as enemy fire. Haeberle responded, "No.... the only American casualty I believe that I witnessed, is that person [U.S. soldier] who...shot [himself] in the foot.[1]: pp.508–9 Seymour Hersh, who wrote the first news stories about the massacre, described the enemy as "nonexistent".[35] After all the eventual investigations it became clear there wasn't a single VC in the village. Private First Class Michael Bernhardt, who was there that day, would later testify, "I don't remember seeing one military-age male in the entire place, dead or alive."[36]

Motivation

[edit]Haeberle waited more than a year before he approached The Plain Dealer with his photos and story. During this time, he created a slideshow and gave talks about his experiences to civic groups and a high school. "The first slides he showed were innocuous: troops with smiling Vietnamese kids; medics helping villagers. Then images of dead and mutilated women and children filled the screen. 'There was just disbelief,' Haeberle said of the reaction. 'People said, "No, no, no. This cannot have happened."'"[2] "One woman said it was a staged production. No one wanted to accept it."[32]

In mid-August 1969, the Army's Criminal Investigation Division (CID) questioned Haeberle. The Army was facing mounting pressure caused by letters written to thirty members of Congress, plus the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the President by Ronald Ridenhour, a former Army door gunner who was convinced that something "rather dark and bloody" had happened at Mỹ Lai.[37][38] CID had begun an internal investigation of the massacre. The lead investigator told Haeberle details he didn't know: "babies, women, teens raped and mutilated." "It bothered me," Haeberle wrote later, "I thought to myself, You know, maybe the public ought to know what is going on in Vietnam." "I didn't believe in the antiwar protests and the violence, but as soon as I knew it was women and girls—and what age they were—I couldn't accept it."[32]

As he explained during the Congressional investigation, this is when he decided to go to his local newspaper. He was asked a number of times why he had gone to the press. He described how the Army had called and said "Don't do it," but that he decided to publish anyway. He explained "I just felt the public should know what actually happened, what actually went on, transpired." He was asked again, "You say you wanted the public to know?" and he said "Yes." When asked again he said, "I just wanted to get if off my chest, let the people know exactly what happened." He described how as he found out more about what happened that day he "became more disgusted." He decided to approach the editor of his college newspaper who had become a writer for The Plain Dealer. He told him the story and how he felt and said, "I don't want any money. Just print it."[1]: pp.534, 536, 267

He also knew and wanted others to know that it wasn't just Mỹ Lai: "Everybody said, Oh it was Charlie Company, Charlie Company. But what about B Company, where ninety-plus civilians were massacred in My Khe?"[32]

Controversy

[edit]Haeberle was criticized by the Army and Congressional investigations into the massacre for not reporting what he witnessed or turning in his color photographs. The Army's report said he "withheld and suppressed from proper authorities the photographic evidence of atrocities he had obtained" despite "having a particular duty to report any knowledge of suspected or apparent war crimes".[39] The congressional subcommittee "subjected Haeberle to exhaustive questioning" about why he failed to report what he had seen to his command, and they "badgered him about why he had been carrying" a personal camera and what he "intended to do with the pictures".[5]

He responded that "he had never considered" turning in his personal color photos. He explained, "If a general is smiling wrong in a photograph, I have learned to destroy it.... My experience as a G.I. over there is that if something doesn’t look right, a general smiling the wrong way...I stopped and destroyed the negative." He felt his photographs would never have seen the light of day if he had turned them in.[40] It was confirmed in the U.S. Army's own investigation that Haeberle had, in fact, been reprimanded for taking pictures which "were detrimental to the United States Army."[41] Fear was on his mind as well; as he explained to a reporter, he feared the troops "might have shot him, too, had he stood in their way."[42] And he wasn't just worried about himself. "We had other servicemen in the Public Information Office and Jay [Roberts] still had a year to go. Something could have happened to one of the people in our office. Their lives would be in danger, easily disposed of, it's called 'fragging'. I had only a couple of weeks to go but something could have happened to one of them if they went on another mission with a camera. Everyone was afraid to tell the truth, including us. Look at what happened, it was covered up all the way from the top down. We definitely had a part in the cover-up, it's something we should have reported."[33]: p.183

As became clear during the investigations, this was not an unusual sentiment among U.S. troops. Another member of Charlie Company present at Mỹ Lai explained: "You'd expect if you had knowledge of a murder, it would be incumbent on you to do something about it. But there wasn't an avenue to do it and you certainly had second thoughts about taking that kind of a stand.... You got to remember that everybody there has a gun in his hand.... I wasn't prepared to single myself out at that point. You feel like a pretty small pawn in a great big game."[33]: p.82

Returning to Vietnam

[edit]

Haeberle has returned to Vietnam numerous times. In 2000 he biked 646 miles from Hue to Ho Chi Minh City and he returned to the area of the massacre for the first time.[12][43] The massacre has "been etched in his mind", and every time he returns to the Mỹ Lai area he "feels emotional." He goes there "out of respect for the survivors and those who lost their lives during the four hours I was in Sơn Mỹ". He has also met with survivors of the massacre. In 2011 he met Duc Tran Van—"Duc was 8 years old in March 1968, and as Haeberle spoke with him, through an interpreter, he realized with a jolt that the woman he had photographed dead [next to her bamboo hat] years earlier was Duc’s mother, Nguyen Thi Tau."[2] (see photograph 3 above) Duc told Haeberle that his mother had told him to try to escape "carrying his fourteen-month-old little sister, Ha, who had been wounded in the abdomen." When Duc heard a helicopter above them, he threw himself to the ground covering his sister.

By chance, Haeberle had photographed that moment as well (see image on left with Duc on top protecting his sister Thu Ha Tran). Haeberle had assumed that the two children he had photographed on the trail that day had been killed. He has since also met the sister Ha, and a third surviving sister My, who escaped from under a pile of bodies. The four have become friends (see image of all four at right). Since Haeberle took the last photo of Duc's mother, he gave Duc the historic camera he used that day.[12][44]

Humanitarian work

[edit]Haeberle has helped raise money for several humanitarian efforts in Vietnam, including for the relief of flood and typhoon victims, and for Project RENEW, which works to make Vietnam safe from unexploded American bombs and mines that still remain in the country. In 2021 he led an effort to raise $28,000 after a series of storms and tropical depressions devastated areas of central Vietnam. Haeberle said, "I have been committed to doing all I can to help the people of Vietnam ever since I personally witnessed American war crimes at My Lai."[45] The RENEW project works to remove and destroy unexploded bombs remaining from the war, teaches children to avoid contact with cluster bombs and other dangerous explosives, and assists the innocent victims still suffering from the war.[46] In March 2023, Haeberle visited a secondary school in Quang Ngai City, near where the massacre occurred, and gave 100 Project RENEW "gift sets to the students, each containing a school bag, pen pouch, and a raincoat."[44]

Awards

[edit]The Vietnamese people and government have expressed their appreciation to Haeberle for helping to bring the massacre to the attention of the world, as well as for the humanitarian work he does in Vietnam. On the 50th anniversary of the Paris Peace Accords (2013-2023), the Vietnam Union of Friendship Organizations presented Haeberle with an award "for peace and friendship among nations", honoring his contributions to helping to end the "US war in Vietnam, addressing the consequences of the war, [and] reconciling and promoting the Vietnam-US people-to-people exchanges."[47] Haeberle was also honored in March 2023 by the leaders of Quang Ngai province who presented him with a gift and framed thank you letter in appreciation for the photos of the massacre he took in their province in 1968, as well as for his efforts towards peace.[48]

Photos displayed

[edit]In Vietnam

[edit]

Ho Chi Minh City

[edit]Currently Haeberle's photos are on display in two prominent museums in Vietnam. The first is in Ho Chi Minh City at the War Remnants Museum, which contains exhibits relating to the First Indochina War and the Second Indochina War (the Vietnam War in the United States). This museum is the most popular museum in the city, attracting approximately half a million visitors every year.[49][50]

Sơn Mỹ

[edit]

The second is the Sơn Mỹ Memorial Museum which is located at the site of the massacre and includes the remains of the village of Sơn Mỹ in Quảng Ngãi Province.[51][52] A large black marble plaque just inside the entrance to the museum lists the names of all 504 civilians killed by the American troops, including "17 pregnant women and 210 children under the age of 13."[53][54] A number of enlarged versions of Haeberle's photos are shown inside the museum.[44] The images are dramatically backlit in color and share the central back wall with a life-size recreation of American soldiers "rounding up and shooting cowering villagers."[55] The museum also celebrates American heroes, including Ronald Ridenhour who first exposed the killings, as well as Hugh Thompson and Lawrence Colburn who intervened to save a number of villagers.[53]

At the center of the museum grounds, which is at the heart of the destroyed village, is a large stone monument. The two children to the lower right in the sculpture are modeled on the two children in one of Haeberle's photos, often called "Two Children on a Trail". As mentioned above, they have now been identified as Duc Tran Van and his sister Thu Ha Tran.[56]

In the United States

[edit]Haeberle's photos have been exhibited as a part of two of the most recent university stops on the Waging Peace in Vietnam book tour and exhibit ("U.S. Soldiers and Veterans Who Opposed the War") which has visited colleges and universities around the United States. Haeberle wrote the section of the book on the Mỹ Lai massacre. His photos are shown in a separate display due to their graphic nature—"My Lai: A Massacre That Took 504 Souls, And Shook the World." The display includes, for the first time anywhere, all 18 of his color photos from the massacre. The first showing, at the University of San Diego, was in March 2022.[57] The second was at the University of Alaska Southeast in Juneau during the months of November and December 2022.[58]

Conclusion

[edit]In 2018, for the 50th anniversary of the massacre, Time magazine revisited the publication of Haeberle's photos. Mỹ Lai, they observed, was "hardly the only instance of rape or murder by U.S. troops in Vietnam." In fact, as Nick Turse summarized in Kill Anything That Moves, his encyclopedic examination of U.S. atrocities during the Vietnam War, "the stunning scale of civilian suffering in Vietnam is far beyond anything that can be explained as merely the work of some 'bad apples,' however numerous. Murder, torture, rape, abuse, forced displacement, home burnings, specious arrests, imprisonment without due process — such occurrences were virtually a daily fact of life throughout the years of the American presence in Vietnam. And..., they were no aberration. Rather, they were the inevitable outcome of deliberate policies, dictated at the highest levels of the military."[23] Nonetheless, as Time concluded, "because of Haeberle’s photographs — it remains the emblematic massacre of the war." In other words, Haeberle's photos made all the difference—they were that important. Despite it all, Time described him as "thoughtful", a "plainspoken man" who "never sought the spotlight".[2]

See also

[edit]- And babies

- Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War

- Project RENEW - works to make Vietnam safe from unexploded American bombs and mines

- Sir! No Sir!, a documentary about the anti-war movement within the ranks of the United States Armed Forces

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Investigations, United States. Congress. House. Committee on Armed Services. Armed Services Investigating Subcommittee (1976). Investigation of the My Lai Incident, Ninety-First Congress, Second Session. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ a b c d e f g Theiss, Evelyn (2018-03-15). "The Photographer Who Showed the World What Really Happened at My Lai". Time. Retrieved 2023-06-11.

When Haeberle's shocking photographs of their atrocities were published — more than a year later — the pictures laid bare an appalling truth: American "boys" were as capable of unbridled savagery as any soldiers, anywhere.

- ^ Becker, Elizabeth (2004-05-27). "Kissinger Tapes Describe Crises, War and Stark Photos of Abuse". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

In their conversation on Nov. 21, 1969, about the My Lai massacre, Mr. Laird told Mr. Kissinger that while he would like to sweep it under the rug, the photographs prevented it.There are so many kids just laying there; these pictures are authentic, Mr. Laird said.

- ^ Oliver, Kendrick (2006). The My Lai Massacre in American History and Memory. Manchester University Press. pp. 36&39. ISBN 9780719068911.

Feher himself recalled that he did not obtain 'hard evidence that something real bad had happened' until he interviewed Ronald Haeberle on 25 August and was shown Haeberle's photographs of the massacre victims.(p.36) ...the interview indicated to Pentagon officials that news of the massacre could not be contained."(p.39)

- ^ a b Belknap, Michael R. (2002). The Vietnam War on Trial: The My Lai Massacre and the Court-Martial of Lieutenant Calley. University Press of Kansas. pp. 112&140. ISBN 9780700612116.

- ^ Investigations, United States. Congress. House. Committee on Armed Services. Armed Services Investigating Subcommittee (1976). Investigation of the My Lai Incident, Ninety-First Congress, Second Session. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 267.

Mr. Stratton: You said that you had two black and white cameras and one color camera. Mr. Haeberle: That is right.

- ^ a b c Cosgrove, Ben (1969-12-05). "American Atrocity: Remembering My Lai". LIFE. Retrieved 2023-06-11.

Incredibly, the world at large might have never learned about the death and torture visited by American troops upon the villagers at My Lai had it not been for an Army photographer named Ron Haeberle.

- ^ a b c d e f Corrigan, Jo Ellen (2009-11-20). "Plain Dealer exclusive in 1969: My Lai massacre photos by Ronald Haeberle". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved 2023-06-11.

- ^ M. Paul Holsinger (1999). "And Babies". War and American Popular Culture. Greenwood Press. p. 363. ISBN 9780313299087.

The Vietnam War produced thousands of shocking photographs of death and destruction, but few scenes were more disturbing than the horrific color picture of dozens of dead South Vietnamese women and children taken by combat photographer Ronald Haeberle

- ^ Turse, Nick (2013-08-28). "Was My Lai just one of many massacres in Vietnam War?". bbc.com. BBC News Service. Retrieved 2023-06-22.

The result was industrial-scale slaughter, the equivalent, he said, to a 'My Lai each month'.

- ^ Matthew Israel (2013). Kill for Peace: American Artists Against the Vietnam War. University of Texas Press. p. 130.

- ^ a b c d e f g Grogan, David (2022-06-16). "Sergeant Ron Haeberle, U.S. Army – A Photo of Future Hope". davidegrogan.com. WordPress. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ "Selective Service System: Induction Statistics". sss.gov. U.S. Government. 2023-06-11. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Ronald Haeberle". artefactshistory.net. Squarespace. Retrieved June 13, 2023.

Up to this point Mr Haeberle's year [sic] in Vietnam with the Public Information Office had mainly consisted of recording official events.

- ^ "Viet Cong". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved June 13, 2023.

The name is said to have first been used by South Vietnamese Pres. Ngo Dinh Diem to belittle the rebels.

- ^ "Ronald Haeberle". artefactshistory.net. Squarespace. Retrieved June 13, 2023.

Ronald Haeberle had no idea that anything out of the ordinary would happen on this assignment.

- ^ Greiner, Bernd (2010). War Without Fronts: The USA in Vietnam. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300168044.

- ^ Allard, Sam (2019-11-20). "Plain Dealer Published Photos of My Lai Massacre in Vietnam 50 Years Ago Today". clevescene.com. Euclid Media Group, LLC. Retrieved 2023-06-13.

Fifty years ago today, the Cleveland Plain Dealer...published shocking photos of the My Lai Massacre in Vietnam.

- ^ Department of the Army. Report of the Department of the Army Review of the Preliminary Investigations into the My Lai Incident, Volumes I–III (1970).

- ^ [1]" VOV News, 16 March 2012.

- ^ a b "The My Lai Massacre: Report of the Department of the Army Review (1970)". digitalhistory.uh.edu. Digital History. 1970. Retrieved 2023-06-13.

During or subsequent to the briefing, LTC Barker ordered the commanders of C/1-20 Inf, and possibly B/4-3 Inf, to burn the houses, kill the livestock, destroy foodstuffs and perhaps to close the wells. No instructions were issued as to the safeguarding of noncombatants found there.

- ^ Balestrieri, Steve (2018-05-15). "Captain Ernest Medina, Commander During My Lai Massacre Dies at 81". sofrep.com. SOFREP. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

Medina briefed his men that they were to kill all guerrilla and North Vietnamese combatants, including "suspects" (including women and children, as well as all animals), to burn the village, and pollute the wells.

- ^ a b Turse, Nick (2013). Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam. Henry Hold and Company. pp. 227–8. ISBN 9780805086911.

- ^ Raviv, Shaun (Jan 2018). "The Ghosts of My Lai". smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

In a hotel room in Ohio, before a stunned investigator, Haeberle projected on a hung-up bedsheet horrifying images of piled dead bodies and frightened Vietnamese villagers.

- ^ Brownmiller, Susan (1975). Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape. Simon & Schuster. pp. 103–05. ISBN 978-0-671-22062-4.

- ^ Murder in the name of war: My Lai, BBC News, 20 July 1998.

- ^ Wieskamp, Valerie (2013-10-29). "My Lai, Sexual Assault and the Black Blouse Girl: Forty-Five Years Later, One of America's Most Iconic Photos Hides Truth in Plain Sight". readingthepictures.org. Reading the Pictures. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

In their historical overview of the massacre, James Olson and Randy Roberts compile information about sexual violence from the Peers Inquiry to produce a list of 20 acts of rape based on eyewitness testimony. The victims documented on this list ranged from age 10-45. Of these women and girls, nine were under the age of eighteen. Many of these assaults were gang rapes and many involved sexual torture.

- ^ "Report of the Department of Army review of the preliminary investigations into the Mỹ Lai incident. Volume II, Exhibits, Book 14 – Testimony, 14 March 1970" (PDF). Library of Congress. p. 22.

- ^ "Charlie Company and the Massacre". pbs.org. PBS. Retrieved 2023-06-17.

- ^ "My Lai Exhibit" (PDF). wagingpeaceinvietnam.com. Waging Peace in Vietnam. Retrieved 2023-06-17.

- ^ "My Lai photographer Ron Haeberle admits he destroyed pictures of soldiers in the act of killing". 20 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d Carver, Ron; Cortright, David; Doherty, Barbara, eds. (2019). Waging Peace in Vietnam: U.S. Soldiers and Veterans Who Opposed the War. Oakland, CA: New Village Press. pp. 75–78. ISBN 9781613321072.

- ^ a b c d Bilton, Michael; Sim, Kevin (1993). Four hours in My Lai. Penguin Books. ISBN 0140177094.

- ^ Hersh, Seymour (1969-11-20). "Hamlet attack called 'point-blank murder'". pulitzer.org. St. Louis Post Dispatch. Retrieved 2023-06-16.

The Viet Cong body count was listed as 128 and there was no mention of civilian casualties.

- ^ Hersh, Seymour (1972-01-14). "The Massacre at My Lai". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2023-06-16.

...all these factors combined to enable a group of normally ambitious men to mount an unnecessary mission against a nonexistent enemy force and somehow find evidence to justify it.

- ^ Powell, Gayle (2009-11-20). "Eyewitness accounts of the My Lai massacre; story by Seymour Hersh Nov. 20, 1969". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved 2023-06-11.

We met no resistance and I only saw three captured weapons. We had no casualties. It was just like any other Vietnamese village-old Papa-Sans, women and kids. As a matter of fact, I don't remember seeing one military-age male in the entire place, dead or alive.

- ^ "Ron Ridenhour letter". Famous Trials. 29 March 1969. Retrieved 2023-06-16.

- ^ Raviv, Shaun (Jan 2018). "The Ghosts of My Lai". smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

Ridenhour's letter spurred the inspector general of the Army, Gen. William Enemark, to launch a fact-finding mission

- ^ "Summary of Peers Report". 2001.

- ^ Hersh, Seymour (1972-01-14). "The Massacre at My Lai". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2023-06-16.

- ^ "REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY REVIEW OF THE PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATIONS INTO THE MY LAI INCIDENT, Vol II, Book 14" (PDF). tile.loc.gov. Library of Congress. 2011-10-26. p. 100. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

- ^ Retter, Emily (2018-03-16). "'Soldiers were almost robotic as they massacred civilians': Man who exposed Vietnam's My Lai atrocity reveals its full horror". mirror.co.uk. Mirror.

- ^ "US photographer of My Lai massacre returns to Vietnam". sggp.org.vn. Saigon News. 2011-10-26. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ a b c "Photos of Son My massacre to be displayed again". sggp.org.vn. Saigon News. 2023-03-11. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ Anh, Phan (2021-01-14). "US veterans donate $28,000 for central Vietnam flood relief". e.vnexpress.net. VN Express. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

The campaign was organized by Ron Haeberle, the American photographer best known for capturing the My Lai Massacre in 1968

- ^ "RENEW Fundraisers in Virginia and DC". landmines.org.vn. RENEW. 2023-06-13. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ "VUFO's insignias presented to US friends". en.vietnamplus.vn. Vietnam Plus. 2023-06-17. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ "Photographer taking pictures of Son My massacre returns to Vietnam". english.vov.vn. VOV. 2023-03-09. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ "When the Whole Village Died – My Lai Massacre". roughguides.com. Rough Guides. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

This museum is the city's most popular attraction but not for the faint-hearted.

- ^ "Introduction general". warremnantsmuseum.com. War Remnants Museum. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ Lendon, Brad (2021-03-21). "My Lai: Ghosts in another Vietnam wall". cnn.com. CNN Travel. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

The pictures, taken by a US Army combat photographer, were horrifying. Piles of bodies, looks of terror on Vietnamese faces as they stared at certain death, a man shoved down a well, homes set ablaze.

- ^ "When the Whole Village Died – My Lai Massacre". whattawowworld.com. What a Wow World. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ a b Raviv, Shaun (January 2018). "The Ghosts of My Lai". smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

- ^ Tamashiro, R (2018). "Bearing Witness to the Inhuman at Mỹ Lai: Museum, Ritual, Pilgrimage". ASIANetwork Exchange: A Journal for Asian Studies in the Liberal Arts. 25. ASIANetwork Exchange: 60–79. doi:10.16995/ane.267. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ Kucera, Karil (2008). "REMEMBERING THE UNFORGETTABLE: THE MEMORIAL AT MY LAI" (PDF). castle.eiu.edu. Studies on Asia. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ Sen (2019-05-17). "Tale of children who survived My Lai massacre falls on deaf ears". e.vnexpress.net. VN Express. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

As Tran Van Duc and his sister Tran Thi Ha escaped from the armed men carrying out a grisly massacre, a helicopter flew low over them. Duc threw himself on his sister to protect her. Ronald L. Haeberle, a combat photographer on duty Vietnam, captured that moment.

- ^ Wilkens, John (2022-03-19). "Then and now: Famous My Lai photographs displayed at USD while war in Ukraine rages" (PDF). San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ Moniak, Rich (2022-11-21). "Opinion: The power in attempting to memorialize the truth". juneauempire.com. Juneau Empire. Retrieved 2023-06-20.