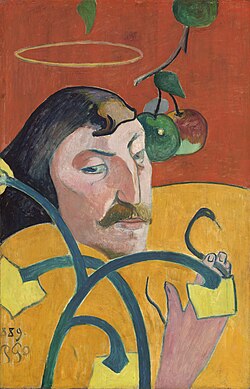

Self-Portrait with Halo and Snake

| Self-Portrait | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Paul Gauguin |

| Year | 1889 |

| Type | Oil painting on wood |

| Dimensions | 79 cm × 51 cm (31.2 in × 20.2 in) |

| Location | National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. |

Self-Portrait with Halo and Snake, also known as Self-Portrait, is an 1889 oil-on-wood painting by French artist Paul Gauguin, which represents his late Brittany period in the fishing village of Le Pouldu in northwestern France. No longer comfortable with Pont-Aven, Gauguin moved on to Le Pouldu with his friend and student Meijer de Haan and a small group of artists. He stayed for several months in the autumn of 1889 and the summer of 1890, where the group spent their time decorating the interior of Marie Henry's inn with every major type of art work. Gauguin painted his Self-Portrait in the dining room with its companion piece, Portrait of Jacob Meyer de Haan (1889).

The painting shows Gauguin against a red background with a halo above his head and apples hanging beside him as he holds a snake in his hand while plants or flowers appear in the foreground. The religious symbolism and the stylistic influence of Japanese wood-block prints and cloisonnism are apparent. The portrait was completed several years before Gauguin visited Tahiti and is one of more than 40 self-portraits he completed during his lifetime.[note 1] The work reached the art market in 1919 when Marie Henry sold it at the Galerie Barbazanges in Paris as part of her collected works from the Le Pouldu period. American banker Chester Dale acquired the painting in 1928, gifting it upon his death in 1962 to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Background

[edit]Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) was a French Post-Impressionist artist and figure in the Symbolist movement known for his contributions to the Synthetist style. In 1886, he spent the summer in Pont-Aven in Brittany, an artists colony that became known as the Pont-Aven School for Gauguin's influence and the work they produced. In late 1888, Gauguin painted for nine weeks with Vincent van Gogh at his Yellow House in Arles in the south of France before van Gogh had a breakdown, leading him to cut off his ear and be hospitalized. Gauguin left Arles and never saw van Gogh again, but they continued to exchange letters and ideas.[1][2]

He briefly returned to Paris where he lived with painter Émile Schuffenecker, but returned to Pont-Aven in the spring of 1889 only to find it too crowded. Gauguin moved farther away "to escape the tourists and the Parisian and foreign painters"[3] and arrived at Le Pouldu on October 2, 1889. He found lodgings with Meijer de Haan at Buvette de la Plage, an inn run by Marie Henry. De Haan introduced Gauguin to Thomas Carlyle's novel Sartor Resartus (1836) by way of conversation. Although he would not read the novel for several more years, Gauguin became acquainted with Carlyle's ideas which would influence his approach to art during this time.[4]

The interior of Marie Henry's inn became their canvas, and they painted their work on the walls, ceilings, and windows.[5][6] They were later joined by artists Paul Sérusier and Charles Filiger. According to Nora M. Heimann, when the room was completed, it "encompassed paintings of every major type—genre, landscape, self-portraiture, portraiture, still life, and even history painting—in media ranging from tempera and oil on plaster to oil on canvas and panel; as well as prints and drawings; painted and glazed ceramic vessels; exotic found objects; and carved, polychromed figures in wood."[7]

Gauguin tried to win the affection of Marie Henry, the innkeeper, but she spurned his advances and became intimate with de Haan instead, leaving Gauguin jealous.[8] Gauguin departed on November 7, 1890, leaving his work at Marie Henry's inn.[note 2] She retired in 1893 and moved to Kerfany, taking many of the art works with her. She continued to lease the inn until 1911 when she sold it. When the new owner was redecorating the inn in 1924, which by then had been converted into a restaurant, the rest of the murals were discovered buried intact under wallpaper.[7]

Development

[edit]Van Gogh had previously decorated rooms with his paintings, in particular the rooms of several restaurants in Paris and the Yellow House in Arles. Gauguin and de Haan appear to have been influenced by this work, as they began decorating the dining room of Buvette de la Plage in a similar fashion. Gauguin's Self-Portrait was prepared along with its pendant, Portrait of Jacob Meyer de Haan (1889), to the right and left respectively of a fireplace on the upper panels of two wooden cupboard doors. Gauguin gave the panels a subtle, textured matte surface using white chalk ground and a combed wave pattern. Both works were completed sometime between mid-November and mid-December 1889.[5][7][9]

Description

[edit]French art historian Françoise Cachin notes that Gauguin designed both Self-Portrait with Halo and Snake and its companion piece Portrait of Jacob Meyer de Haan as a caricature.[10] In his Self-Portrat, Gauguin appears against a red background with a halo above his head and apples hanging beside him as he holds a snake in his hand with what appear to be either plants or flowers in the foreground.[2][11] Curator Philip Conisbee observes the religious symbolism in the images, noting that the "apples and snake refer to the Garden of Eden, temptation, sin, and the Fall of Man."[12] Gauguin divides the canvas in half, painting himself as both saint and sinner, reflecting his own personal myth as an artist. In the top portion of the painting, Gauguin is almost angelic with the halo, looking away from the apples of temptation. In the bottom portion, he holds the snake, completing the duality.[1][13][14]

Jirat-Wasiutyński notes that art historian Denys Sutton was the first critic to interpret Gauguin's self-portrait as "demonic".[11] This interpretation is illustrated by the pendant, the companion piece Portrait of Jacob Meyer de Haan (1889), which visually complements the Self-Portrait. De Haan's devilish eyes and red hair shaped like horns in his portrait on the left side of the dining room where it was created in situ, corresponds to the snake held in Gauguin's hand in his self-portrait on the right door of the dining room.[15] Two books appear on the table in de Haan's portrait: Paradise Lost (1667–74) by seventeenth-century English poet John Milton, and Sartor Resartus by Thomas Carlyle. These respective literary allusions, to Milton's Satan and to Carlyle's Diogenes Teufelsdröckh, a character described as both angelic and diabolical, play directly into de Haan's and Gauguin's corresponding self-portraits. Jirat-Wasiutyński argues that Gauguin portrays himself as a magus, as "both seer and demonic angel".[11]

The work shows the influence of Japanese wood-block prints and cloisonnism.[12] In the painting, Gauguin wears what art historian Henri Dorra compares to the saffron colored robe of a Buddhist monk, perhaps influenced by Van Gogh's earlier Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin (1888).[15] In a letter to Gauguin dated October 3, 1888, Van Gogh describes himself in the self-portrait as "a character of a bonze, a simple worshiper of the eternal Buddha".[16][17] Compared to Gauguin's more traditional Self-Portrait Dedicated to Carrière (1888 or 1889), the self-portrait painted at Le Pouldu is more "sinister".[2]

Provenance

[edit]

In 1919, Marie Henry sold Gauguin's Self-Portrait as part of a batch of 14 other works to François Norgelet for a total of 35,000 francs, where it was exhibited at the Galerie Barbazanges in Paris. Although ownership details are scant, the painting is thought to have passed through the hands of several owners, including London art collector Mrs. R. A. Workman and later Lord Ivor Spencer-Churchill. It was sold by Churchill to the galleries Alex Reid and Lefèvre in 1923, who then sold it to Kraushaar Galleries in 1925. American banker Chester Dale acquired the work in 1928.[18] The painting was later bequeathed by Dale to the National Gallery of Art in 1962 after his death. The Chester Dale Collection opened at the National Gallery in 1965.[2][19]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Altogether, he made more than 40 self-portraits." See "Two Faces of Paul Gauguin". National Gallery of Art.

- ^ Gauguin sued to get his work back from Marie Henry but lost the case. See Welsh-Ovcharov, Bogomila (2001). "Paul Gauguin's Third Visit to Brittany – June 1889 – November 1890". p. 28 in Eric M. Zafran (Ed.) Gauguin's Nirvana: Painters at Le Pouldu 1889–90.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Maurer, Naomi E. (1998). The Pursuit of Spiritual Wisdom: The Thought and Art of Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 79–82, 134–136. ISBN 978-0-8386-3749-4.

- ^ a b c d Strieter, Terry W. (1999). Nineteenth-century European Art: A Topical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 83–84, 225–226. OCLC 185705650. ISBN 978-0-313-29898-1.

- ^ Kearns, James (1989). Symbolist Landscapes: The Place of Painting in the Poetry and Criticism of Mallarmé and His Circle. London: Modern Humanities Research Association. p. 9. OCLC 20302344. ISBN 978-0-947623-23-4.

- ^ Gamboni, Dario (2015). Paul Gauguin: The Mysterious Centre of Thought. Reaktion Books. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-78023-368-0.

- ^ a b Welsh, Robert (2001) "Gauguin and the Inn of Marie Henry at Pouldu". In Eric M. Zafran (Ed.) Gauguin's Nirvana: Painters at Le Pouldu 1889–90. pp. 61–80. Yale University Press. OCLC 186413251. ISBN 978-0-300-08954-7.

- ^ Pickvance, Ronald (1986). Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-87099-477-7

- ^ a b c Heimann, Nora M. (Summer 2012). "Spinner or Saint: Context and Meaning in Gauguin's First Fresco." Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, 11 (2).

- ^ Kole, William J. (January 26, 2001). "Exhibition examines 'the odd couple' of Post-Impressionism." Bangor Daily News, p. D3.

- ^ Jirat-Wasiutynski, Vojtech; H. Travers Newton Jr. (2000). Technique and Meaning in the Paintings of Paul Gauguin. Cambridge University Press. pp. 172–179. OCLC 40848521. ISBN 978-0-521-64290-3.

- ^ Cachin, Françoise (1988). "Self-portrait with Halo". In Richard Brettell, Françoise Cachin, Claire Frèches-Thory, and Charles F. Stuckey (Ed.), The Art of Paul Gauguin (pp. 56, 165–167). National Gallery of Art. ISBN 0-89468-112-5.

- ^ a b c Jirat-Wasiutyński, Vojtěc (Spring 1987). "Paul Gauguin's 'Self-Portrait with Halo and Snake': The Artist as Initiate and Magus." Art Journal, 46 (1): 22–28. (subscription required)

- ^ a b Conisbee, Philip (November 22, 2013). Self-Portrait, Gauguin. National Gallery of Art. Event begins at 0.54. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- ^ Matheny, Lynn Kellmanson (2011). "Gauguin: Maker of Myth." Exhibition brochure. National Gallery of Art.

- ^ National Gallery of Art (2013).An Eye for Art: Focusing on Great Artists and Their Work. Chicago Review Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-61374-897-8.

- ^ a b Dorra, Henri (2007). The Symbolism of Paul Gauguin: Erotica, Exotica, and the Great Dilemmas of Humanity. University of California Press. p. 19, 124–126. OCLC 475909736. ISBN 978-0-520-24130-5.

- ^ Van Gogh, Vincent (October 3, 1888)."To Paul Gauguin. Arles." Van Gogh Museum. Huygens Institute. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ Silverman, Deborah (2004). Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Search for Sacred Art. Macmillan. p. 27, 41–42. ISBN 978-0-374-52932-1.

- ^ "Provenance". Self-Portrait. National Gallery of Art. "Consigned by the artist to Mme Marie Henry [1859–1945], Le Pouldu, in lieu of rent; sold 1919 through François Norgelet ... receipt signed by Marie Henry for 35,000 francs for 14 paintings sold to Norgelet, dated 3 June 1919, archives of the Barbazanges-Hodebert Gallery". Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- ^ Bruner, Louise (May 5, 1965). "Gallery Unveils Bequest of Dale." Toledo Blade, p. 32.

Further reading

[edit]- Amishai-Maisels, Ziva (1985). Gauguin's Religious Themes. Garland. OCLC 12188712. ISBN 978-0-8240-6863-9.

- Henderson, Linda Dalrymple (Spring 1987). "Mysticism and Occultism in Modern Art." Art Journal, 46 (1): 5–8. (subscription required)

- Southgate, M Therese (August 2000). "The Cover: Self-portrait." JAMA, 284 (8): 929. doi:10.1001/jama.284.8.929.

- Sutton, Denys (October 1949). "The Paul Gauguin Exhibition." The Burlington Magazine, 91 (559): 283–286. (subscription required)

- Swindle, Stephanie (May 2010). "Paul Gauguin and Spirituality". Pennyslyvania State University. Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture. Thesis.

External links

[edit]