Timeline of Brexit

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Brexit |

|---|

|

| Withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union Glossary of terms |

Brexit was the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union at 23:00 GMT on 31 January 2020 (00:00 1 February 2020 CET). As of 2020[update], the UK is the only member state to have left the EU. Britain entered the predecessor to the EU, the European Communities (EC), on 1 January 1973. Following this, Eurosceptic groups grew in popularity in the UK, opposing aspects of both the EC and the EU. As Euroscepticism increased during the early 2010s, Prime Minister David Cameron delivered a speech in January 2013 at Bloomberg London, in which he called for reform of the EU and promised an in–out referendum on the UK's membership if the Conservative Party won a majority at the 2015 general election. The Conservatives won 330 seats at the election, giving Cameron a majority of 12, and a bill to hold a referendum was introduced to Parliament that month.

In February 2016, Cameron set the date of the referendum to be 23 June that year, and a period of campaigning began. A total of 33,577,342 votes were cast in the poll, with 51.89% voting for Britain to leave the EU. Cameron announced his resignation as prime minister the next day, with Theresa May taking over the position on 13 July. On 29 March the following year, May delivered a letter to Donald Tusk, the President of the European Council, which officially commenced the UK's withdrawal from the EU and began a two-year negotiating process.

Brexit negotiations between the UK and the EU began in June 2017, and, by March the following year, a "large part" of the withdrawal agreement had been agreed.[1] On 25 November, the leaders of the remaining 27 EU countries officially endorsed the deal, with May putting it to Parliament in January 2019. The vote on the withdrawal agreement was defeated by 432 votes to 202, the biggest defeat of any government in the House of Commons. Two further votes on the deal—on 12 and 29 March—also resulted in large defeats for May.

Following these defeats, on 24 May the Prime Minister announced her resignation. A leadership contest began, which was won by Boris Johnson on 24 July. With the Brexit deadlock still not broken, on 29 October the Members of Parliament (MPs) voted in favour of holding a general election on 12 December. The Conservative Party won 365 seats in the election, giving them a majority of 80 seats. With a majority in the House of Commons now, Johnson's withdrawal agreement was voted through Parliament, and the UK officially left the EU at 23:00 GMT on 31 January 2020. A transition period—in which Britain remained a part of the European single market and the European Union Customs Union—began, as did negotiation on a new trade deal.

After negotiations throughout 2020, the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement was announced on 24 December, allowing goods to be sold between the two markets without tariffs or quotas. At 23:00 on 31 December 2020, the transition period ended, and the UK formally completed its separation from the EU. As of 2023[update], the broad consensus of economists is that leaving the EU has had a substantially negative effect on the UK's economy, which is expected to be several percentage points smaller than it would have been if it had remained in the bloc.[2][3][4]

Background

[edit]United Kingdom–European Union relations

[edit]

The UK entered the EC on 1 January 1973, following the ratification of the Treaty of Accession 1972, signed by the Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath.[6] Two years later, on 5 June 1975, a national referendum endorsed the UK's continued membership of the EC, with 67.23% voting that the country should remain in the EC.[7] Over the following decades, Eurosceptic attitudes began to develop within Britain's two main political parties, the Conservatives and the Labour Party. In the 1983 general election, Labour's campaign manifesto vowed to withdraw from the EC within the lifetime of the following Parliament.[8] The manifesto was dubbed "the longest suicide note in history", and the election was won by the Conservatives, led by the incumbent prime minister, Margaret Thatcher.[9] Thatcher continued to serve as prime minister until she resigned on 22 November 1990, amid divisions within the Conservative Party over the UK's involvement in Europe.[10] Two years later, the Maastricht Treaty was signed by the 12 member states of the EC, including the UK, which began the formal establishment of the European Union.[5]

Political history of the United Kingdom (2005–13)

[edit]

On 6 December 2005, David Cameron, the MP for Witney, was elected as leader of the Conservative Party, beating David Davis in the final round.[11] After serving as leader of the opposition for nearly five years, Cameron led his party into the 2010 general election on 6 May that year.[12] The Conservatives gained 97 seats for a total of 307, making them the largest party in Parliament.[13] Labour, who had been in government before the election, won 258 seats, while the Liberal Democrats, with 57 seats, were the third-largest party.[13] With no single party having won enough seats to form a majority government, the country had its first hung parliament since 1974.[14] All three leaders made statements offering openness to creating an administration with another party, and a series of negotiations began.[15] Just after midnight on 12 May, the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition agreement was approved, with Cameron as prime minister and Nick Clegg, the leader of the Liberal Democrats, as deputy prime minister.[16]

As well as a new prime minister, the 2010 general election also saw a new generation of more Eurosceptic MPs elected to the UK government.[17] On 24 October 2011, Cameron experienced the largest rebellion over European integration since World War II when 81 Conservative MPs voted in favour of a motion calling for a referendum on the UK's membership of the EU.[18] Of these 81 MPs, 49 had been elected in 2010.[19] The previous month, a petition carrying over 100,000 signatures that also called for a referendum was delivered to 10 Downing Street.[20] Faced with this growing Euroscepticism, on 23 January 2013, Cameron delivered the Bloomberg speech at Bloomberg London,[21] in which he promised an in–out referendum on EU membership if the Conservatives won a majority at the 2015 general election.[22]

Brexit

[edit]The word Brexit is a portmanteau of the phrase "British exit".[23] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term was coined in a blog post on the website Euractiv by Peter Wilding, director of European policy at BSkyB, on 15 May 2012.[24] Wilding coined Brexit to refer to the end of UK membership in the EU – by 2016, usage of the word had increased by 3,400% in one year.[25]

Pre-referendum

[edit]2013

[edit]- 23 January: Cameron delivers the Bloomberg speech, covering the UK's future relationship with Europe. He calls for reform of the EU and promises an in–out referendum on the UK's membership of the EU if the Conservatives win a majority at the 2015 general election.[22]

- 15 April: The House of Commons votes on a private member's bill expressing "regret" over the absence of an EU referendum in the Queen's Speech. The vote is defeated by 277 to 130, with 114 Conservative MPs voting to regret.[26]

- 19 June: The European Union (Referendum) Bill 2013–14—a private member's bill seeking to enshrine into law Cameron's promise to hold a referendum—is introduced by the Conservative MP James Wharton.[27][28]

- 5 July: The bill passes its second reading in the House of Commons by 304 votes in favour to 0 against.[29]

2014

[edit]- 31 January: Peers at the House of Lords vote by 180 to 130 to end the debate of the European Union (Referendum) Bill 2013–14, which concludes its progress through Parliament. Cameron expresses disappointment at this defeat.[30]

- 12 March: Ed Miliband, the leader of the Labour Party, rules out matching Cameron's pledge to hold a referendum on EU membership if his party wins a majority at the next general election. He states that Labour would only hold such a poll if there were a significant transfer of power from Westminster to Brussels.[31]

- 22 May: The UK holds elections to the European Parliament, electing 73 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs). Across England, Scotland and Wales, the Conservatives' share of the vote drops by 3.8 percentage points, losing them seven seats.[32]

- 12 June: Conservative MP Bob Neill announces that he will reintroduce Wharton's European Union (Referendum) Bill as a private member's bill.[33]

- 28 October: The Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats fail to agree on the amount of parliamentary time to be allocated to Neill's bill. The bill's progress through Parliament is again brought to an end.[34]

- 19 December: The "long campaign" for the 2015 general election officially begins, limiting candidates' spending in their constituencies to £30,700 each.[35]

2015

[edit]- 30 March: Cameron meets with Queen Elizabeth II at Buckingham Palace and informs her that the 55th UK Parliament is ready to be dissolved.[36] The "short campaign" for the general election—scheduled to take place on 7 May—begins.[37]

- 12 April: In central London, Clegg launches his party's manifesto for the general election, which commits to maintaining the UK's membership of the EU.[38][39]

- 13 April: The Labour Party's manifesto is unveiled by Miliband at the Old Granada Studios in Manchester. It repeats Miliband's earlier pledge that, under a Labour government, powers would not be transferred to Brussels before an in–out referendum.[40]

- 14 April: Cameron launches the Conservative Party manifesto at an event in Swindon.[41] The document promises "real change" in the UK's relationship with the EU, and commits to holding a referendum on EU membership before the end of 2017.[42]

- 24 April: At Chatham House in London, Miliband delivers a speech on Labour's foreign policy.[43] He describes the government's timetable for an in–out referendum as "arbitrary", and criticises their lack of strategy for renegotiating the UK's EU membership.[44]

- 25 April: Writing for The Sunday Telegraph, Cameron reiterates his promise that, should the Conservatives win a majority, they will begin the process of renegotiating the UK's membership of the EU, and will draft a European Referendum Bill.[45][46]

- 7 May: The 2015 general election is held. The Conservative Party win 330 seats, giving Cameron a 12-seat overall majority in Parliament. Labour win 232 seats in total, a net loss of 26, while the Liberal Democrats win eight, a net loss of 49.[47][48]

- 8 May: Following Labour's and the Liberal Democrats' defeats at the election, both Miliband and Clegg resign as the leaders of their parties.[49][50]

- 27 May: A referendum on EU membership before the end of 2017 is included in the Queen's Speech.[51]

- 28 May: The European Union Referendum Bill 2015–16—a bill that makes provision for a referendum in the UK to be held—is introduced by the Conservative MP Philip Hammond.[52]

- 9 June:

- The bill passes its second reading in the House of Commons by 544 votes in favour to 53 against.[53]

- Nominations open for the Labour Party leadership election, triggered by Miliband's resignation.[54]

- 15 June: Nominations close for Labour's leadership election. Four MPs surpass the threshold of support required and are set to be placed on the ballot: Andy Burnham, Yvette Cooper, Liz Kendall and Jeremy Corbyn.[55]

- 25–26 June: At a European Council meeting, Cameron begins renegotiating Britain's EU membership with other EU leaders by setting out his plan to hold a referendum.[56][57]

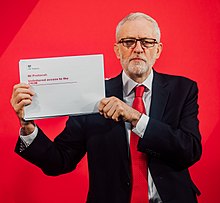

- 12 September: The results of Labour's leadership election are announced at a special conference at the Queen Elizabeth II Centre in Westminster.[59] With 59.5% of the first-preference votes, Corbyn is elected leader of the Labour Party and becomes leader of the opposition.[58]

- 9 October: Vote Leave, a cross-party advocacy group campaigning for the UK to leave the EU, is launched.[60]

- 12 October: Britain Stronger in Europe, a similar organisation advocating for Britain to remain, is launched.[61]

- 10 November: Cameron gives a speech on Europe at Chatham House, during which he repeats his commitment to holding a referendum before the end of 2017.[62] He also sends a letter to Donald Tusk, the President of the European Council, setting out the four areas where he is seeking EU reform as part of his renegotiations: economic governance, competitiveness, sovereignty and immigration.[63]

- 17 December: The European Union Referendum Bill 2015–16 is given royal assent and becomes the European Union Referendum Act 2015. By law, a referendum on membership in the EU is set to take place in the UK before the end of 2017.[52]

2016

[edit]- 10 January: In his annual new year interview on The Andrew Marr Show, Cameron vows that he will stay on as prime minister if the UK votes to leave the EU,[64] but states that his government has made no plans to deal with Brexit.[65][66]

- 19 February: Renegotiations on the UK's membership in the EU are concluded, with Cameron and Tusk signing a finalised deal. The changes will take effect following a vote to remain in the referendum.[67]

- 20 February:

- Cameron announces that the referendum will be held on 23 June, and that he will be campaigning for Britain to remain.[68]

- Six members of Cameron's cabinet declare that they will join Vote Leave and campaign for Brexit.[69]

- 21 February: Mayor of London Boris Johnson announces that he will advocate for the UK to leave the EU.[70]

- 22 February: Speaking in the House of Commons, Cameron promises that, if the British people vote to leave, he will begin the process, i.e., by triggering Article 50 of the EU's Treaty of Lisbon, "straight away".[71]

- 11–13 April: A pro-EU leaflet—in which the government warns that Brexit will increase the cost of living and lead to a decade or more of uncertainty[73][74]—is sent to households across England.[72]

- 13 April: The Electoral Commission designates Vote Leave as the referendum's official campaign in favour of leaving the EU, while Britain Stronger in Europe is named as the official campaign in favour of remaining.[75]

- 15 April: The regulated campaigning period for the referendum begins. Over the next ten weeks, the two official campaigns may spend a maximum of £7 million.[75]

- 22 April: At a press conference in central London, President of the United States Barack Obama warns that Britain will be at "the back of the queue" if the nation votes for Brexit.[76]

- 9 May: The pro-EU leaflet is sent to households in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.[77]

- 9 June: Six participants—including Johnson—take part in The ITV Referendum Debate, a live TV debate on Brexit, broadcast by ITV.[78]

- 12 June: In another interview on The Andrew Marr Show, Cameron repeats his commitment not to resign as prime minister even if he loses the referendum.[79]

- 16 June: Jo Cox, the MP for Batley and Spen, is murdered by a far-right terrorist.[80] Out of respect for Cox, referendum campaigning is suspended across the UK.[81]

- 19 June: Campaigning for the referendum resumes.[82]

- 21 June: From Wembley Arena, Johnson and another five campaigners participate in EU Referendum: The Great Debate, live on BBC One. With 6,000 people in the audience, it is the largest televised debate on the issue.[83]

- 23 June: Polls open for the referendum at around 41,000 polling stations at 07:00 and close at 22:00.[84] A total of 33,577,342 votes are cast, representing a turnout of 72.2% of registered voters.[85]

Post-referendum

[edit]2016

[edit]

- 24 June:

- The votes are counted, and chief counting officer Jenny Watson delivers the final result from Manchester at 07:20 BST: 16,141,241 votes (48.11%) to remain in the EU, and 17,410,742 (51.89%) to leave.[87]

- Following the result of the referendum, the value of the pound sterling drops to its lowest level since 1985, and the FTSE 100 Index begins the day by falling 8%.[88]

- Stating that he does not believe that he should be "the captain that steers [the] country to its next destination", Cameron announces that he plans to resign as prime minister and leader of the Conservative Party by October.[86]

- 25 June: The UK's European Commissioner, Jonathan Hill, announces his intention to stand down from the role.[89]

- 27 June: In Parliament, Cameron confirms that he will not invoke Article 50.[90]

- 29 June: Nominations open for the Conservative Party leadership election triggered by Cameron's resignation.[91]

- 30 June: Nominations for the leadership contest close. Johnson confirms that he will not stand.[92] Five other MPs—Theresa May, Andrea Leadsom, Michael Gove, Stephen Crabb and Liam Fox—achieve the level of support needed to be put on the first ballot.[93]

- 7 July: Only two nominees, May and Leadsom, now remain in the leadership race, with the rest having either withdrawn or been eliminated.[94]

- 11 July: Leadsom withdraws from the contest early. As the only remaining candidate, May is named the new leader of the Conservative Party.[95]

- 13 July:

- Cameron tenders his resignation as prime minister to the Queen at Buckingham Palace.[96]

- The Queen invites May to form a new government as Cameron's replacement. May builds her cabinet, appointing Hammond as Chancellor of the Exchequer, Amber Rudd as Home Secretary, Johnson as Foreign Secretary and Davis to the newly created post of Brexit secretary.[97]

- 19 July:

- The first legal challenge over Brexit, R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union, is brought by investment manager Gina Miller and hairdresser Deir Dos Santos. The High Court hears details of the case—which asks whether Parliament or the prime minister has the authority to begin the process of Britain withdrawing from the EU—in a preliminary hearing.[98]

- The government confirms that May will not start the formal process by officially invoking Article 50 before the end of the year.[99]

- 27 July: President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker appoints French politician Michel Barnier as the chief negotiator for the UK leaving the EU.[100]

- 12 September: Cameron resigns as the MP for Witney, ending his political career.[101]

- 2 October:

- The 2016 Conservative Party Conference begins in Birmingham.[102] Speaking on The Andrew Marr Show ahead of the conference, May reveals that she will invoke Article 50 in the first quarter of 2017.[103]

- In his opening speech at the conference, Davis announces that the government will repeal the European Communities Act 1972, the act that originally made legal provision for the UK's membership of the EEC.[104]

- 5 October: May gives her closing speech at the Conservative Party conference, during which she signals her intentions to control immigration from Europe and to leave the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (ECJ).[105]

- 10 October: From the despatch box in the House of Commons, Davis gives a speech to MPs assuring them that there would be "only a considerable upside" to Brexit, and that there would not be a downside.[106]

- 2 November: The Collins English Dictionary selects Brexit as the word of the year for 2016.[107]

- 3 November: In the Miller case, a panel of three judges in the High Court find in the claimants' favour, and rules that the prime minister cannot decide to trigger Article 50 without a vote in Parliament first. The government indicates that it will appeal the decision at the Supreme Court.[108]

- 4 November: Writing for the pro-Brexit newspaper the Daily Mail, political editor James Slack calls the three judges "enemies of the people" in an article on the High Court's ruling. Slack's article draws more than 1,000 complaints to the Independent Press Standards Organisation.[109]

- 2 December: At Chatham House, Johnson gives his first policy speech as foreign secretary, in which he sets out his vision for the UK after Brexit. He states that, after leaving the EU, the UK will not obstruct closer European defence co-operation.[110]

- 5–8 December: The Supreme Court convenes to hear the government's appeal against the High Court ruling. For the first time in the history of the court, all 11 judges sit en banc to hear the case.[111]

- 7 December: The House of Commons votes on a motion brought by the Labour Party committing the government to publishing its Brexit plan before it invokes Article 50, and also on an amendment added by May for Article 50 to be invoked before the end of March 2017. MPs vote by 461 to 89 in favour of May's amendment, and by 448 to 75 in favour of the amended motion.[112]

2017

[edit]- 3 January: Urging in his resignation email for civil servants to challenge "ill-founded arguments and muddled thinking", Ivan Rogers steps down from his role as Permanent Representative of the United Kingdom to the European Union.[113]

- 4 January: May appoints career diplomat Tim Barrow to replace Rogers.[114]

- 17 January: In a speech at Lancaster House in Westminster, May lays out her "Plan for Britain" following Brexit, including 12 negotiating priorities.[115] She rules out remaining in the single market or customs union.[116]

- 24 January: By a majority of eight judges to three, the Supreme Court dismiss the government's appeal of the Miller case, and rule that a vote in Parliament is required before Article 50 can be invoked.[117]

- 26 January: In Parliament, Davis introduces the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill, a 137-word bill that can give May the power to formally begin the Brexit process by triggering Article 50. Corbyn says that he will instruct Labour MPs to support it.[118]

- 1 February: The bill passes its second reading in the House of Commons by 498 votes in favour to 114 against.[119]

- 2 February: The government publishes its Brexit plan in a white paper, setting out its strategy for exiting the EU.[120]

- 16 March: The bill receives royal assent and becomes the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017.[121]

- 29 March: In Brussels, Barrow hand delivers a letter from May to Tusk that officially invokes Article 50. A two-year negotiating process begins, with the UK due to leave the EU on 29 March 2019.[122] Speaking at a press conference immediately afterwards, Tusk says that there is "no reason to pretend that this is a happy day".[123]

- 30 March: The government publishes the "Great Repeal Bill" white paper, laying out its plans for legislating on Brexit, including transferring EU regulations into UK legislation.[124]

- 18 April: After chairing a meeting of her cabinet, May announces her intention to call a snap general election on 8 June.[125]

- 19 April: In the House of Commons, MPs pass a motion for an early general election, providing the legal framework for one to be held on 8 June.[126]

- 16 May: The Labour Party launches its manifesto for the election, which includes accepting the referendum result.[127]

- 18 May: The Conservatives publish their manifesto. The document repeats May's earlier commitment that the UK "will no longer be members of the single market or customs union",[128] and proposes new changes to social care: in the means test for receiving free care in their own home, a person's property would be included as well as their savings and income.[129]

- 22 May: Following a backlash to the proposed reforms, May announces an "absolute limit" on the amount of money that a person would have to pay for social care.[130]

- 8 June: The general election is held, with 32,204,184 votes being cast for a turnout of 68.7%.[131] The Conservatives win 318 seats in total, a net loss of 13. Although still the largest party in the House of Commons, they no longer have a parliamentary majority, resulting in a hung parliament.[132]

- 9 June: As leader of the largest party in the Commons, May is invited by the Queen to form a new government. She signals her intention to enter into a confidence-and-supply arrangement with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) of Northern Ireland, led by Arlene Foster.[133]

- 19 June: Davis travels to Brussels for the first round of Brexit negotiations with Barnier.[134]

- 21 June: In the Queen's Speech, eight bills that prepare the UK for Brexit are announced.[135]

- 26 June: The Conservative–DUP agreement is finalised, with the DUP agreeing to support the Conservatives on legislation relating to security and Brexit.[136]

- 13 July: In Parliament, the government introduces the Great Repeal Bill (now called the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill) to the House of Commons.[137]

- 27 July: Rudd commissions the Migration Advisory Committee to produce a report analysing the social and economic contributions and costs of EU citizens in the UK.[138]

- 22 September: May delivers a speech from Florence. She proposes a two-year "transition" period after Brexit, during which the current arrangements for market access will continue to apply.[139]

- 1 October: An anti-Brexit march takes place outside the Conservative Party Conference in Manchester. Speeches are delivered by Vince Cable, the leader of the Liberal Democrats, and the Conservative politician Stephen Dorrell.[140]

- 8 December: The EU and UK publish a joint report on the progress made during the first round of negotiations,[141] allowing them to move talks to the next stage.[142]

- 13 December: In the House of Commons, MPs vote on an amendment to the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill tabled by the MP Dominic Grieve, which seeks to secure a "meaningful vote" on any withdrawal agreement. Eleven Conservative MPs vote in favour of the amendment, which passes by 309 votes to 305. It is May's first Commons defeat over Brexit legislation.[143]

- 15 December: The EU announces that "sufficient progress" has been made in the first phase of Brexit negotiations, and that talks can proceed to the second phase.[144]

2018

[edit]- 17 February: Speaking at the Munich Security Conference, May calls for continued co-operation on security after Brexit.[145]

- 20 February: Davis delivers a speech in Vienna, in which he pledges that Britain will keep co-operating with EU regulatory authorities in order to ensure a "future economic partnership".[146]

- 26 February: In a speech at Coventry University, Corbyn confirms that Labour will support a customs union with the EU, and that his party will directly oppose May's refusal to enter one.[147]

- 28 February: The European Commission publish a 118-page proposed Brexit withdrawal agreement, which translates the joint report published on 8 December 2017 into a draft legal text. Speaking at Prime Minister's Questions, May says that the Commission's proposed agreement would "undermine the UK common market".[148]

- 2 March: May gives a speech at Mansion House, London, repeating that Britain will leave the single market and the customs union, and that the jurisdiction of the ECJ in the UK would end. Barnier welcomes this "clarity".[149]

- 19 March: In Brussels, Davis and Barnier announce that they have reached a "broad agreement" of the withdrawal agreement, and that a "large part" of it has been agreed.[1] A draft version of the agreement is published.[150]

- 16 May: The European Union (Withdrawal) Bill enters its third reading at the House of Lords.[137] The Lords propose 15 amendments to the bill.[151]

- 28 June: The bill is granted royal assent and becomes the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018.[137]

- 6 July: May chairs a meeting of her cabinet at Chequers, the prime minister's country residence, to discuss and agree on a collective approach for future negotiations on Brexit. The agreement becomes known as the Chequers plan.[152]

- 9 July:

- Davis resigns as Brexit secretary, followed by his deputy Steve Baker. In his resignation letter, Davis criticises the Chequers plan, saying that it is "certainly not returning control of our laws in any real sense".[153] May appoints Dominic Raab to replace him.[154]

- Johnson resigns as foreign secretary, stating in his letter than the Chequers plan "sticks in the throat".[155] He is replaced by Jeremy Hunt.[156]

- 20 July: As part of a two-day visit to Northern Ireland, May delivers a speech in Belfast calling for a new deal with the EU on the Republic of Ireland–United Kingdom border.[157]

- 24 July: The government publishes a white paper on how the withdrawal agreement will be put into law.[158]

- 23 August: Raab releases 25 "technical notices", which detail how individuals and businesses can prepare in the event that the UK leaves the EU without the withdrawal agreement being approved by both sides (known as a "no-deal Brexit").[159]

- 19–20 September: Following a European Council meeting in Salzburg, Tusk warns in a statement that the Chequers plan will not work as it "risks undermining the single market".[160]

- 29 October: In the 2018 budget, Hammond increases spending on preparations for Brexit by an additional £500 million.[161]

- 13 November: Using a humble address, Labour tables a motion to force the government to publish the legal advice it has received on the withdrawal agreement before a Brexit deal is put to Parliament. After the DUP comes out in favour of the motion, ministers order Conservative MPs to abstain from voting on it, and it subsequently passes without a vote.[162]

- 14 November: The EU and UK negotiating teams agree on the draft text of the withdrawal agreement, which is published as a 585-page document.[163]

- 15 November: Four ministers, including Raab, resign from the government. Raab writes in his resignation letter that he "cannot in good conscience" support the agreement.[164]

- 16 November: May appoints Steve Barclay as the new Brexit secretary.[165]

- 25 November: EU leaders officially endorse the withdrawal agreement, with Juncker saying that it is "the best deal possible" and "the only deal possible".[166]

- 4 December: Five days of parliamentary debate on Brexit (scheduled for 4–6 and 10–11 December) begin.[167]

- 10 December: On the penultimate day of debate, May gives a statement to the House of Commons, stating that Parliament's first meaningful vote on the deal—scheduled for the following day—will be postponed so that she can seek "further assurances" from the EU.[168] In a post on Twitter, Corbyn calls this a "desperate step".[169]

- 12 December:

- Graham Brady, chairman of the 1922 Committee, announces that he has received letters of no confidence in May from at least 48 Conservatives MPs, exceeding the threshold of 15% of all Conservative MPs. He declares that a vote of no confidence in May's leadership will be held between 18:00 and 20:00 that evening.[170]

- The confidence vote is held, with May winning by 200 to 117.[171]

2019

[edit]- 9 January:

- The House of Commons begins a second five-day period of parliamentary debate on Brexit.[172]

- Grieve tables an amendment to a business motion saying that, if May loses the vote on her withdrawal agreement, she must return to the Commons with a new plan for Brexit within three working days, rather than the 21 days plus seven sitting days normally permitted.[173] Grieve's amendment passes by 308 votes to 297.[174]

- 15 January:

- The first meaningful vote on the withdrawal agreement is held in the House of Commons. The government is defeated by 432 votes against to 202 in favour. With a margin of 230, it is the largest defeat of any government in the House of Commons.[175]

- Corbyn describes the defeat as "catastrophic", and tables a vote of confidence in the government.[175][176]

- 16 January: MPs vote in the confidence ballot brought by Corbyn. The DUP vote with the government, which wins by 325 to 306.[177]

- 21 January:

- May delivers a statement to the House of Commons on her government's approach to Brexit following the parliamentary defeat.[178]

- Speaking on the BBC Two documentary series Inside Europe: Ten Years of Turmoil, Tusk claims that Cameron did not think he would need to hold the EU referendum, as he expected that, after the 2015 general election, he would enter into another coalition government with the Liberal Democrats, who would then block the poll.[179] Tusk's claims are rejected on Twitter by Craig Oliver, Cameron's former Downing Street Director of Communications.[180]

- 29 January: The government tables a motion on its Brexit plans to the House of Commons, which votes on seven amendments to May's statement. Two amendments—one brought by Brady; the other by Caroline Spelman—are passed.[181]

- 11 March: May travels to Strasbourg for a meeting on the withdrawal agreement with Juncker and Barnier. In a statement afterwards, she says that she has secured "legally binding" changes that "strengthen and improve" the Brexit deal.[182]

- 12 March: The House of Commons holds the second meaningful vote on the deal. MPs again reject the deal, this time by 391 votes against to 242 in favour, a majority of 149.[183]

- 13 March: Spelman's amendment to the government's Brexit plans—that the UK must not leave the EU without a deal—is debated by the House of Commons. MPs vote in favour of the amendment, thereby rejecting a no-deal Brexit, by 312 to 308.[184]

- 14 March: With the UK set to leave the EU on 29 March without a deal in place, MPs vote on an amended motion on whether Article 50 should be extended beyond 29 March. By 413 votes to 202, the motion passes.[185]

- 18 March: Citing a convention dating back to 1604, John Bercow, the speaker of the House of Commons, rules that the government cannot present the withdrawal agreement for a third meaningful vote without substantial changes to it first.[186]

- 20 March: May writes a letter to Tusk, requesting an extension of the Article 50 period until 30 June 2019.[187]

- 21 March: The European Council agree that the Article 50 period can be extended to 22 May if Parliament votes to accept the withdrawal agreement, but only to 12 April otherwise.[188]

- 23 March: A march organised by the group People's Vote—who are campaigning for another referendum on Brexit—takes place in London.[189] Researchers at Manchester Metropolitan University estimate the number in attendance to be between 312,000 and 400,000.[190]

- 27 March:

- Bercow selects eight Brexit plans from MPs that might win the support of the majority of the House of Commons. MPs debate and vote on all eight options in a series of "indicative votes", but each one is rejected by the House.[191]

- Speaking to the 1922 Committee, May promises to resign as Conservative leader and prime minister if MPs pass the withdrawal agreement.[192]

- 29 March:

- 1 April: Bercow selects another four possible Brexit plans from MPs, which are then debated and voted on. All four are defeated.[195]

- 2 April: In a televised address from 10 Downing Street, May reveals that she will ask for a further extension to Article 50, and offers to meet with Corbyn to get a deal through Parliament. Corbyn welcomes her attempt to "reach out".[196]

- 5 April: May writes to Tusk and requests that Brexit be delayed until 30 June.[197]

- 10 April: The European Council meet, and agree that the Article 50 period be extended to 31 October 2019, or the first day of the month after a withdrawal agreement is agreed by both the UK and the EU. The EU leaders stress that, if the UK is still a member between 23 and 26 May, then it will have to hold elections to the European Parliament.[198]

- 7 May: With the bipartisan talks between the Conservatives and Labour having not yet reached an agreement, David Lidington, minister for the Cabinet Office, confirms that Britain will participate in the European Parliament elections.[199]

- 17 May: Talks between the Conservatives and Labour break down without an agreement, as Labour withdraws from them.[200]

- 21 May: May unveils a new withdrawal agreement: a package of 10 commitments aimed at reaching a compromise in Parliament.[201]

- 23 May: The UK holds elections to the European Parliament. At 37.2%, turnout is the second-highest in any European election in the country.[202] The Conservatives lose 15 seats with a vote share of 9.1%,[203] making it their worst result in a national election since 1832.[204]

- 24 May: May announces that she will resign as prime minister and leader of the Conservative Party, effective 7 June, and that she will continue as caretaker prime minister until a new leader is chosen.[205]

- 31 May: An opinion poll of voting intentions by the market research firm YouGov puts the Liberal Democrats in first place with 24%.[206] It is the first time in nine years that such a poll has not been topped by either the Conservatives or Labour.[207]

- 7 June: Nominations open at 10:00 in the leadership election to replace May. They close again at 17:00, with ten candidates—including Johnson, Hunt, Gove, Raab and Leadsom—having received enough endorsements to be placed on the first ballot.[208][209]

- 20 June: Johnson and Hunt are the only two remaining candidates in the contest, with the rest having either been eliminated or withdrawn. The winner is set to be selected in a ballot by members of the Conservative Party.[210]

- 2 July: EU leaders elect Charles Michel as the new president of the European Council, replacing Tusk.[211]

- 16 July: Ursula von der Leyen is elected the new president of the European Commission. She replaces Juncker.[212]

- 18 July: MPs approve, with a majority of 41, an amendment to the Northern Ireland (Executive Formation etc) Act 2019 that blocks suspension of Parliament between 9 October and 18 December, unless a new Northern Ireland Executive is formed.[213]

- 23 July: The result of ballot of Conservative Party members is announced at the Queen Elizabeth II Centre. With 92,153 votes to Hunt's 46,656, Johnson is elected the new leader of the party.[214]

- 24 July:

- 25 July: Johnson appoints his cabinet. Barclay remains as Brexit secretary, while Raab becomes foreign secretary.[217]

- 18 August: Barclay signs an order to repeal the European Communities Act 1972, ending all EU laws in the country when Britain leaves the union. Speaking afterwards, he describes the signing as a "landmark moment".[218]

- 28 August: Johnson asks the Queen to prorogue Parliament, suspending parliamentary business from 9 September to 14 October.[219] The Queen approves this timetable at a meeting of the Privy Council at Balmoral Castle.[220]

- 2 September: In response to the prorogation, Hilary Benn publishes a draft text of the European Union (Withdrawal) (No. 6) Bill, which will legislate that, if a withdrawal agreement is not passed by Parliament by 19 October, then the prime minister must seek an extension to the Article 50 period to 31 January 2020.[221]

- 3 September:

- Phillip Lee, a Conservative MP, crosses the floor to join the Liberal Democrats. In doing so, Johnson loses his majority in the House of Commons.[222]

- Conservative MP Oliver Letwin tables a motion for Benn's bill to be passed through each stage of the House of Commons the following day. The motion passes by 328 to 301, with 21 Conservative MPs voting to support it.[223]

- 4 September:

- Conservative Chief Whip Mark Spencer phones the 21 MPs who voted in favour of Letwin's motion to suspend them from the Conservative Party.[224] Johnson now has a majority of minus 43.[225]

- The European Union (Withdrawal) (No. 6) Bill passes all its stages in the House of Commons. In its third reading, MPs vote in its favour by 327 to 299.[226]

- 5 September: Answering a question during a Q&A at a police training college in Wakefield, Johnson asserts that he would rather be "dead in a ditch" than request another extension to the Article 50 period.[227]

- 6 September: A panel of three senior judges in the High Court in England reject an appeal brought by Miller against the prorogation, R (Miller) v The Prime Minister, and rule that the decision is not justiciable, i.e., it is a political question rather than a legal one. The court therefore declines to intervene.[228][229]

- 9 September:

- Benn's bill achieves royal assent and becomes the European Union (Withdrawal) (No. 2) Act 2019.[231]

- Bercow announces his intention to resign as speaker of the house either before or on 31 October, the day that Britain is due to leave the EU.[230]

- On the advice of Johnson, the Queen prorogues Parliament until the Queen's Speech on 14 October.[232]

- 11 September: In the case of Cherry v Advocate General for Scotland, appeal court judges in Scotland rule that Johnson's decision to prorogue Parliament is unlawful. The government say that they are disappointed in the decision, and will appeal it in the Supreme Court.[233]

- 24 September: The Supreme Court delivers its verdict on the Miller and the Cherry cases. Sitting en banc for only the second time in the court's history, the judges unanimously reverse the High Court's decision, saying that Johnson's decision is justiciable. They also rule that the prorogation was "unlawful, null and of no effect", i.e., Parliament was never prorogued.[229]

- 25 September: Following the Supreme Court's verdict, MPs are recalled to the House of Commons.[234]

- 3 October: In the House of Commons, Johnson gives a statement on his proposals for a new withdrawal agreement.[235]

- 8 October: In anticipation of the UK leaving the EU without an agreement, the government publishes the "No-Deal Readiness Report", outlining its plans for a no-deal Brexit.[236]

- 10 October: After three hours of discussion at Thornton Manor in Liverpool, Johnson and Irish Taoiseach Leo Varadkar release a joint statement agreeing on "a pathway to a possible deal".[237]

- 14 October: Parliament returns for the Queen's Speech, which includes seven Brexit-related bills.[238]

- 17 October: The UK and European Commission agree on a revised withdrawal agreement containing a new protocol on Northern Ireland. Juncker recommends to EU leaders that the deal is endorsed.[239]

- 19 October:

- MPs debate the new Brexit deal in a rare Saturday sitting in the House of Commons. To insure against Britain leaving the EU before the withdrawal agreement is ratified, Letwin tables a motion to delay consideration of the agreement until the legislation to implement it has been passed.[240] Letwin's amendment passes by 322 votes in favour to 306 against, requiring Johnson, under the Benn Act, to request another extension to the Article 50 period.[241]

- Johnson sends two letters to Tusk: an unsigned official request to delay Brexit until 31 January 2020, and a signed personal letter explaining his opposition to the delay.[242]

- 21 October: Bercow refuses a request from the government for a new vote on the withdrawal proposal, applying the convention that a motion that is the same "in substance" as an earlier one cannot be brought back during the course of a single parliamentary session.[243]

- 22 October: Speaking in the House of Commons, Johnson announces that the government will pause legislation related to the Brexit deal and will instead "accelerate" preparations for a no-deal Brexit.[244]

- 24 October: Johnson asks Corbyn in a letter to support a government motion for an early general election on 12 December. Corbyn insists that he would not support a general election until the possibility of a no-deal Brexit is removed first.[245]

- 28 October:

- Tusk confirms in a post on Twitter that the leaders of the EU nations have agreed to delay Brexit until 31 January 2020.[246]

- In the House of Commons, the government motion for an early general election on 12 December. Conservative MPs vote in favour, but Labour abstain, and the motion receives only 299 votes, fewer than the two-thirds threshold required under the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 (434 votes).[247]

- 29 October: The government introduces the Early Parliamentary General Election Bill to set aside the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 and hold a general election on 12 December. MPs vote in favour of the bill by 438 to 20.[248]

- 31 October: The bill is given royal assent and becomes the Early Parliamentary General Election Act 2019. A general election will now be held on 12 December.[249]

- 4 November: Replacing Bercow, Lindsay Hoyle is elected the new speaker of the House of Commons.[250]

- 21 November: At an event at Birmingham City University, Corbyn launches Labour's "most radical" manifesto in decades.[251] On Brexit, the manifesto says that Labour would renegotiate a new Brexit deal by March and then put that deal to the public in a referendum within six months.[252]

- 24 November: Johnson unveils the Conservatives' manifesto at the Telford International Centre. He pledges that, if the Conservatives win a majority, he will bring the withdrawal agreement back to Parliament for a vote before Christmas and that the UK will leave the EU by 31 January 2020.[253]

- 6 December: Corbyn accuses Johnson of misrepresenting the impact of his Brexit agreement, as he reveals a leaked document from HM Treasury suggesting that prices will rise and businesses will struggle in Northern Ireland.[254]

- 11 December: At a photo op at a catering company in Derby, Johnson removes a pie from an oven as a metaphor for the Conservatives' "oven-ready" Brexit deal.[255]

- 12 December: The general election is held. A total of 32,014,110 votes are cast for a turnout of 67.3%.[256] The Conservatives win 365 seats, giving them a majority of 80 in the House of Commons. Labour win 203 seats, a net loss of 59.[257]

- 13 December: Following Labour's losses at the election, Corbyn reveals that he will stand down as party leader.[258]

- 20 December: MPs vote in the House of Commons on the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Bill, which would ratify the withdrawal agreement into law. With the Conservatives now having an 80-seat majority, the bill passes its second reading by 358 votes in favour to 234 against, setting Britain on course to leave the EU on 31 January 2020.[259]

2020

[edit]- 8 January: Von der Leyen visits London, and warns at an event that the timeframe to achieve a post-Brexit trade deal is "very, very tight".[260]

- 9 January: The European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Bill passes its third reading by 330 votes in favour to 231 against.[261]

- 23 January:

- The bill receives royal assent and becomes the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020.[262]

- The European Parliament Committee on Constitutional Affairs vote in favour of the withdrawal agreement by 23 votes to three.[263]

- 24 January: Von der Leyen and Michel sign the withdrawal agreement in the EU's Europa building in Brussels. The document is then delivered in a diplomatic bag to Johnson in 10 Downing Street, who also signs it.[264]

- 27 January: Johnson appoints David Frost to lead trade negotiation with the EU on his behalf.[265]

- 28 January: Chris Pincher, Minister of State for Europe and the Americas, becomes the final UK minister to attend an EU meeting as he speaks at the General Affairs Council in Brussels.[266]

- 29 January: MEPs vote to ratify the withdrawal agreement by 621 votes in favour to 49 against. It is the final time that MEPs from the UK sit in the European Parliament.[267]

- 30 January: By responding via email to four yes–no questions, the remaining members of the EU conclude the ratification of the withdrawal agreement.[268]

- 31 January: The UK officially withdraws from the EU at 23:00 GMT. Thousands of Brexit supporters gather in Parliament Square to celebrate the moment. A transition period, where most EU laws will continue to be in force until 31 December, begins.[269]

Transition period

[edit]2020

[edit]- 2 March: Trade talks on the UK and EU's future relationship, led by Barnier and Frost, begin.[270]

- 12 March: As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the UK and EU call off the second round of face-to-face trade talks, and decide instead to explore continuing the negotiations through video conferencing.[271]

- 30 March: The Withdrawal Agreement Joint Committee—a joint committee co-chaired by both the EU and UK, set up to implement the withdrawal agreement—meets for the first time.[272]

- 12 June: At a meeting of the joint committee, Gove formally confirms that the UK will not extend the transition period beyond 31 December.[273]

- 15 June: Johnson, von der Leyen, Michel and President of the European Parliament David Sassoli meet for high-level talks by video conference. In a joint statement afterwards, both sides agreed that the negotiations had been "constructive", but that "new momentum" was needed.[274]

- 8 September: Speaking in the House of Commons, Brandon Lewis, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, says that proposed legislation for the UK's internal market breaks international law "in a very specific and limited way".[275]

- 9 September: The proposed legislation—now called the United Kingdom Internal Market Bill—is published.[276]

- 10 September: Following a meeting between Gove and European Commission Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič, a statement from the European Commission warns that adopting the bill would violate the withdrawal agreement and break international law.[277]

- 16 September: Referencing the internal market bill in her first annual State of the Union address, von der Leyen warns the government against reneging on the withdrawal agreement, and says that it cannot be "unilaterally changed, disregarded, disapplied".[278]

- 29 September: The bill passes its third reading in House of Commons by 340 votes to 256.[279]

- 1 October: Speaking in Brussels, von der Leyen announces that the European Commission has launched legal action against the UK over the internal market bill by writing a letter of formal notice to the government, the first step in an infringement procedure.[280]

- 16 October: In a televised statement, Johnson warns that there will be no more trade negotiations unless there is "fundamental change" to the EU's approach, and that the UK should prepare for a no-deal Brexit.[281]

- 7 November: Johnson and von der Leyen agree to trade negotiations continuing into the following week, and promise to "redouble" the efforts to reach a deal.[282]

- 4 December: Barnier and Frost pause negotiations, saying that the conditions to reach an agreement have not been met.[283]

- 7 December: Von der Leyen and Johnson speak by phone, then say afterwards that significant differences on three issues—fair-competition rules, fishing rights and the governance of future disputes—still remain in the way of a free trade deal.[284]

- 9 December: Johnson travels to Brussels for a three-hour working dinner with von der Leyen. The deadlock is not broken, but both sides agree to a final decision before a deadline of 13 December.[285]

- 13 December: Following a phone call between the pair, Johnson and von der Leyen say that negotiations will continue beyond the deadline. Johnson says that the two sides are "very far apart on some key issues", and that Britain should prepare for tariffs under World Trade Organization terms after the end of the transition period.[286]

- 17 December:

- Speaking on behalf of Johnson, a Downing Street spokeswoman says that it is very likely that a trade agreement will not be reached, as negotiations are in a "serious situation".[287]

- The United Kingdom Internal Market Bill achieves royal assent and becomes the United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020.[288]

- 24 December: The UK and EU reach an agreement on a post-Brexit free trade deal, called the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement. Although the text of the agreement has yet to be released, the deal has been agreed in principle, allowing goods to be sold without tariffs or quotas. Johnson hails the deal as "fantastic news".[289][290]

- 26 December: The full text of the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement, running to more than 1,200 pages, is released.[291]

- 30 December: The government introduces a bill to Parliament to implement the trade deal, with the intention of its passing through all stages in one day. MPs in the House of Commons vote on the bill by 521 in favour to 78 against.[292]

- 31 December:

- The Queen grants royal assent to the bill at 00:35, and it becomes the European Union (Future Relationship) Act 2020, 14 hours after it was introduced.[293][294]

- At 23:00, the UK formally completes its separation from the EU with the ending of the transition period.[295]

Aftermath

[edit]Brexit has had lasting impacts on both the EU and UK, and will continue to for many years.[296][297][298] The broad consensus of economists is that leaving the EU has had a substantially negative effect on the UK's economy.[2] In a January 2021 survey of leading US and European economists, 86% expected that the UK's economy would be several percentage points smaller by 2030 than it would have been if it had remained in the bloc.[299] Two years later, in February 2023, an analysis by Bloomberg Economics concluded that Brexit was costing the UK £100 billion a year in lost output, leaving the country's economy 4% smaller than it otherwise would have been.[3] Similarly, the Office for Budget Responsibility has also forecasted that Brexit will cause Britain's economy to be 4% smaller,[4] and exports and imports to be 15% lower.[300]

As of 2023[update], public opinion of Brexit has also shifted. From 2016 to 2021, views within Britain remained relatively evenly split, with analysts attributing changing patterns to the declining population of elderly Brexit-supporting voters and an increasing number of younger Remain supporters reaching voting age.[2] From 2022 onwards, public opinion changed, with polling conducted by YouGov finding that the public felt that the UK was wrong to leave the EU by 56% to 32%, and that a quarter of Brexit supporters regretted their vote.[2][301] Among Leave voters who regretted their decision, the most common reasons were a feeling that things had gotten worse since the referendum, and concerns over the economy and cost of living.[302] In January 2023, a similar poll by UnHerd and Focaldata concluded that in all but three of Britain's 632 constituencies, a plurality of people agreed that the UK was wrong to leave the EU.[303][304]

See also

[edit]- Timeline of British history (1990–present)

- Timeline of Partygate – a similar political timeline of the UK involving Johnson

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Radosavljevic, Zoran (19 March 2018). "EU, UK make major breakthrough in Brexit talks". Euractiv. Brussels. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d "The Brexit effect". The Week (1423). London: Future: 11. 18 February 2023. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2016. (subscription required)

- ^ a b Concalves, Pedro (1 February 2023). "Brexit 'costing the UK economy £100 billion' a year". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ a b Sleigh, Sophia (26 March 2023). "Brexit Reduces UK's Overall Output by 4% Compared to Remain, Expert Says". HuffPost UK. London. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ a b Palmer, John (7 February 1992). "Second treaty of Maastricht brings full union closer". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ O'Carroll, Lisa (29 January 2020). "The highs and lows of Britain's 47 years in the EEC and EU". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ Hill, Timothy Martyn (25 May 2016). "Forecast error: European referenda, past and present". Significance. London: Oxford University. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ Clark, Neil (10 June 2008). "Not so suicidal after all". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Hope, Christopher (3 March 2010). "Michael Foot: Labour's 1983 general election manifesto and 'the longest suicide in history'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 22 May 2012. (subscription required)

- ^ Kirkup, James (8 April 2013). "Margaret Thatcher: Conflict over Europe led to final battle". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. (subscription required)

- ^ "Cameron chosen as new Tory leader". London: BBC News. 6 December 2005. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Hough, Andrew (11 May 2010). "David Cameron becomes youngest Prime Minister in almost 200 years". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023. (subscription required)

- ^ a b "Election 2010 – Results". London: BBC News. 7 May 2010. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Election 2010: First hung parliament in UK for decades". London: BBC News. 7 May 2010. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "Political uncertainty in UK as rivals jostle for power". CNN. 8 May 2010. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick (12 May 2010). "David Cameron and Nick Clegg lead coalition into power". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "Timeline: Campaigns for a European Union referendum". London: BBC News. 21 May 2015. Archived from the original on 16 October 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Watt, Nicholas (25 October 2011). "David Cameron rocked by record rebellion as Europe splits Tories again". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Redford, Pete. "The EU Referendum rebellion has left David Cameron with little room to manoeuvre and is picking apart his liberal conservative project". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "100,000 sign petition calling for EU referendum". London: BBC News. 8 September 2011. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "David Cameron speech: UK and the EU". London: BBC News. 23 January 2023. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Wright, Oliver; Cooper, Charlie (24 June 2016). "The speech that was the start of the end of David Cameron". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Lewis-Hargreave, Sam (21 January 2019). "Is 'Brexit' the Worst Political Portmanteau in History?". HuffPost UK. London. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Tempest, Matthew (10 January 2017). "Oxford English Dictionary: The man who coined 'Brexit' first appeared on Euractiv blog". Euractiv. Brussels. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Davis, Lindsay (3 November 2016). "'Brexit' tops the list of Collins Dictionary's 2016 words of the year". New York City: Mashable. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick; Watt, Nicholas (16 May 2013). "EU referendum: Cameron snubbed by 114 Tory MPs over Queens' speech". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick; Davies, Caroline (16 May 2013). "EU referendum bill to be put forward by Tory MP". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "European Union (Referendum) Bill". London: UK Parliament. 2013. Archived from the original on 22 February 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Grice, Andrew (5 July 2013). "EU referendum bill: MPs back in/out poll by 304–0". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 15 June 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Craig, Jon (31 January 2014). "EU In–Out Referendum Bill Killed Off by Peers". London: Sky News. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Savage, Michael (12 March 2014). "Miliband won't hold EU vote if he wins election". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2023. (subscription required)

- ^ "Vote 2014". London: BBC News. 23 May 2014. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Ship, Chris (12 June 2014). "Backbench bill puts EU referendum back on the agenda". London: ITV. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "EU referendum bill: Tories accuse Lib Dems of 'killing off' bill". London: BBC News. 28 October 2014. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Chakelian, Anoosh (19 December 2014). "The 2015 election campaign officially begins: what does this mean?". New Statesman. London. Archived from the original on 19 December 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2023. (subscription required)

- ^ McSmith, Andy (30 March 2015). "General Election 2015: They're changing guard at Buckingham Palace...maybe". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "2015 election campaign officially begins on Friday". London: BBC News. 18 December 2014. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "EU referendum bill: Election 2015: Liberal Democrat manifesto at-a-glance". London: BBC News. 15 April 2015. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Keith, Daniel (6 May 2015). "Manifesto Check: Lib Dems as EU 'reformists'". The Conversation. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 18 February 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Mason, Rowena (13 April 2015). "Labour manifesto 2015 – the key points". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 22 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Perraudin, Frances (14 April 2015). "Conservatives election manifesto 2015 – the key points". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Blick, Andrew (2019). Stretching the Constitution: The Brexit Shock in Historic Perspective. London: Bloomsbury. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-50990-581-2. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ a b "April 24th: Ed Miliband does foreign policy". The Economist. London. 24 April 2015. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2023. (subscription required)

- ^ "Full text of Ed Miliband's foreign policy speech at Chatham House". London: LabourList. 24 April 2015. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ Cameron, David (25 April 2015). "David Cameron: We've saved the economy from ruin – don't let Ed Miliband spoil it". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2023. (subscription required)

- ^ Travis, Alan (8 May 2015). "What will the new Tory government do?". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 22 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ "Election 2015 – Results". London: BBC News. 8 May 2015. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Osborn, Matt; Clarke, Seán; Franklin, Will; Straumann, Ralph (8 May 2015). "UK 2015 general election results in full". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 13 September 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "Labour election results: Ed Miliband resigns as leader". London: BBC News. 8 May 2015. Archived from the original on 8 May 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "Election results: Nick Clegg resigns after Lib Dem losses". London: BBC News. 18 December 2014. Archived from the original on 15 May 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "Queen's Speech 2015: EU referendum, tax freeze and right-to-buy". London: BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ a b "European Union Referendum Act 2015". London: UK Parliament. 2015. Archived from the original on 22 February 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "EU referendum: MPs support plan for say on Europe". London: BBC News. 9 June 2015. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Payne, Oliver (15 June 2015). "2015 Labour leadership contest – who's nominated who". The Spectator. London: Press Holdings. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick; Mason, Rowena (15 June 2015). "Labour leftwinger Jeremy Corbyn wins place on ballot for leadership". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Faulconbridge, Guy (26 June 2015). "Cameron says delighted EU renegotiation is underway". London: Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "European Council, 25–26 June 2015". Brussels: European Council. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ a b Mason, Rowena (12 September 2015). "Labour leadership: Jeremy Corbyn elected with huge mandate". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 17 September 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Lowe, Josh (12 September 2015). "Seven things we learned from Labour's leadership race". Prospect. London: Prospect Publishing. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Press Association (9 October 2015). "Millionaire donors and business leaders back Vote Leave campaign to exit EU". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "Pro-EU campaigners launch 'Britain Stronger in Europe' drive". Paris: France 24. 12 October 2015. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Dallison, Paul (10 November 2015). "David Cameron demands EU fixes – or Britain bolts". Politico Europe. Brussels. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Traynor, Ian (10 November 2015). "David Cameron's EU demands letter explained". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "David Cameron vows to stay on as PM in event of Brexit". The Irish Times. Dublin: Irish Times. 10 January 2016. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Savage, Michael; Waterfield, Bruno (11 January 2016). "David Cameron: We have no Brexit plan". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023. (subscription required)

- ^ Barker, Sam (11 January 2016). "David Cameron: We have no plans in event of Brexit". Money Marketing. London. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "European Council, 18–19 February 2016". Brussels: European Council. Archived from the original on 19 December 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "EU referendum: Cameron sets June date for UK vote". London: BBC News. 20 February 2016. Archived from the original on 30 August 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Watt, Nicholas (20 February 2016). "Michael Gove and five other cabinet members break ranks with PM over EU". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Day, Kate (21 February 2016). "Boris Johnson backs Out of Europe push". Politico Europe. Brussels. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Masterman, Roger; Murray, Colin (2022). Constitutional and Administrative Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-009-15848-0. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ a b Belam, Martin (11 April 2016). "Criticism over pro-EU leaflet on Facebook". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 25 November 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ Mayes, Joe; Atkinson, Andrew (9 April 2021). "100 Days of Brexit: Was It as Bad as 'Project Fear' Warned?". New York City: Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2023. (subscription required)

- ^ Stewart, Heather; Mason, Rowena (7 April 2016). "EU referendum: £9m taxpayer-funded publicity blitz pushes case to remain". The Guardian. London. ISSN 1756-3224. OCLC 1149244233. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ a b James, Sam Burne (13 April 2016). "Vote Leave named official Brexit campaign and Stronger In confirmed as pro-EU group". PRWeek. London: Haymarket. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2022. (subscription required)

- ^ Palmer, Doug (22 April 2016). "Obama: Brexit would move U.K. to the 'back of the queue' on U.S. trade deals". Politico Europe. Brussels. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "PM: 'No Apology' for £9.3m Pro-EU Leaflets". London: Sky News. 7 April 2016. Archived from the original on 25 November 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ Withnall, Adam (9 June 2016). "EU referendum ITV debate: Johnson clashes with Remain camp over £350m figure – as it happened". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Withnall, Adam (12 June 2016). "David Cameron says he will not stand down – even if he loses the EU referendum". The Independent. London. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Cobain, Ian; Taylor, Matthew (23 November 2016). "Far-right terrorist Thomas Mair jailed for life for Jo Cox murder". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "EU referendum campaigns suspended until Sunday after Jo Cox attack". London: BBC News. 17 June 2016. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Hume, Tim (30 June 2016). "British MP Jo Cox honored as EU referendum campaigning resumes". CNN. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "EU referendum debate: Who won at Wembley?". The Week. London: Future. 22 June 2016. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Cowburn, Ashley (23 June 2016). "How do I vote in the EU referendum? When do the polls close? Where is my nearest polling station? Everything you need to know". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "Report: 23 June 2016 referendum on the UK's membership of the European Union". London: Electoral Commission. 13 June 2019. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ a b Hughes, Laura (24 June 2016). "An emotional David Cameron says he is not the 'captain' to steer our country to its 'next destination'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 21 April 2023. (subscription required)

- ^ Waldie, Paul (24 June 2016). "The clock struck midnight – and Britain turned into the EU's worst nightmare". The Globe and Mail. Toronto: The Woodbridge Company. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "Pound plunges after Leave vote". London: BBC News. 24 June 2016. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "EU referendum: UK's EU commissioner to resign". London: BBC News. 26 June 2016. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Chadwick, Vince (27 June 2016). "David Cameron: We won't trigger Article 50 now". Politico Europe. Brussels. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Baron and Leadsom expected to launch Conservative leadership bids". London: ITV. 29 June 2016. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Hume, Tim (30 June 2016). "Leading Brexit campaigner Boris Johnson says he won't run for prime minister". CNN. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ "Michael Gove and Theresa May head five-way Conservative race". London: BBC News. 30 June 2016. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "Tory leadership race: Theresa May and Andrea Leadsom make final ballot as Michael Gove is eliminated". Belfast Telegraph. Belfast. 7 July 2016. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Theresa May set to be UK PM after Andrea Leadsom quits". London: BBC News. 7 May 2010. Archived from the original on 11 July 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "David Cameron says being PM 'the greatest honour' in final Downing Street speech". London: BBC News. 7 May 2010. Archived from the original on 11 July 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Boris Johnson made foreign secretary by Theresa May". London: BBC News. 7 May 2010. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ a b Gower, Patrick (19 July 2016). "QuickTake Q&A: Brexit Gets First Challenge in UK Court Case". London: Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2023. (subscription required)

- ^ Chaplain, Chloe (19 July 2016). "Brexit move 'won't happen in 2016' Government tells High Court judge in legal challenge". Evening Standard. London. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "President Juncker appoints Michel Barnier as Chief Negotiator in charge of the Preparation and Conduct of the Negotiations with the United Kingdom under Article 50 of the TEU". Brussels: European Commission. 27 July 2016. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Ending his political career, ex-PM Cameron resigns as an MP". London: Reuters. 12 September 2016. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ "At-a-glance: Guide to Conservative 2016 conference agenda". London: BBC News. 30 September 2010. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Brexit: Theresa May to trigger Article 50 by end of March". London: BBC News. 2 October 2016. Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Elgot, Jessica (2 October 2016). "Theresa May to trigger article 50 by end of March 2017". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ McTague, Tom; Spence, Alex; Charlie, Cooper (5 October 2016). "Theresa May's Brexit 'revolution'". Politico Europe. Brussels. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Parker, George; Allen, Kate (10 October 2016). "David Davis brushes off Brexit retaliation fears". Financial Times. London: Nikkei. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Flood, Alison (2 November 2016). "Brexit named word of the year, ahead of Trumpism and hygge". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Murkens, Jo. "The High Court ruling explained: An embarrassing lesson for Theresa May's government". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Jankowicz, Mia (9 September 2019). "The man behind the Daily Mail's 'Enemies of the People' headline has just been honoured". The New European. London. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Boris Johnson: UK won't block EU defence co-operation". London: BBC News. 2 December 2010. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Holden, Michael (30 November 2016). "Factbox: Brexit case in Britain's Supreme Court – how will it work?". London: Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Johnston, Chris (7 December 2016). "MPs back disclosure of Brexit plan and triggering article 50 by end of March". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Elgot, Jessica; Wintour, Patrick; Walker, Peter (3 January 2017). "Ambassador to EU quits and warns staff over 'muddled thinking'". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick; Asthana, Anushka; Syal, Rajeev (4 January 2017). "Sir Tim Barrow appointed as Britain's EU ambassador". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Ross. "May's 'Plan for Britain' tells us nothing about Brexit. That's quite deliberate". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- ^ Henley, Jon (17 January 2017). "Key points from May's Brexit speech: what have we learned?". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ Bowcott, Owen; Mason, Rowena; Asthana, Anushka (24 January 2017). "Supreme court rules parliament must have vote to trigger article 50". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ King, Esther (26 January 2017). "UK government publishes Brexit bill". Politico Europe. Brussels. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ "Brexit: MPs overwhelmingly back Article 50 bill". London: BBC News. 1 February 2017. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ Henley, Jon (2 February 2017). "Brexit white paper: key points explained". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017". London: UK Parliament. 2017. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2023.