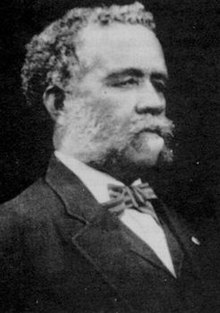

William F. Yardley

William F. Yardley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | William Francis Yardley January 8, 1844[1] |

| Died | May 20, 1924 (aged 80) |

| Resting place | Odd Fellows Cemetery, Knoxville[2] |

| Occupation | Attorney |

| Political party | Republican[3] |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Stone |

William Francis Yardley (January 8, 1844 – May 20, 1924) was an American attorney, politician and civil rights advocate, operating primarily out of Knoxville, Tennessee, in the late 19th century. He was Tennessee's first African-American gubernatorial candidate, and is believed to have been the first African-American attorney to argue a case before the Tennessee Supreme Court.[3] He published a newspaper, the Examiner, that promoted African-American rights, and was an advocate for labor and the poor both as an attorney and as a politician.[3]

Biography

[edit]Yardley was born in 1844 to an Irish mother and a black father, making him free by birth.[4] His mother left him on the doorstep of the Yardley family, a white family who gave him his name and raised him.[3] During the 1850s, he attended a school for colored children taught by St. John's Episcopal Church rector Thomas William Humes.[4] Following the Civil War, Yardley taught at the colored school in Ebenezer, in what is now West Knoxville.[3]

While at Ebenezer, Yardley read law and studied under Knox County judge George Andrews, and passed the bar in 1872. That same year, he was elected to Knoxville's Board of Aldermen, serving one term. As an attorney, Yardley primarily handled criminal cases for black clients, although he also represented the Continental Insurance Company.[3] From 1876 until 1882, he served as justice of the peace for Knox County.[4] In 1878, Yardley began publishing Knoxville's first black newspaper, the Knoxville Examiner. He established a second newspaper, the Bulletin, in 1882.[3]

In Tennessee's gubernatorial election of 1876, Yardley ran as an independent after the state's Republicans decided not to oppose Democrat James D. Porter. Campaigning across the state, Yardley spoke against segregation, called for an overhaul of labor laws, and denounced a state law allowing first class train fares for second class passengers, which hurt the poor.[1] He was complimented for his oratorical abilities by numerous newspapers,[1] but attacked by others, such as the Knoxville Tribune, which called him an "egotistical darky who practices law when he is sober enough and not engaged in doing the dirty work for the Republican machine."[5] Out of five candidates in the election, Yardley placed fourth, with less than one percent of the vote.[6]

In 1885, he is believed to have become the first African American attorney to appear before the Tennessee Supreme Court when he argued against a practice that required jail inmates to work to pay for the costs of their prosecution. He lost the case, but the practice was abolished in later years.[3]

In October 1919, Yardley served on the defense team in the high-profile trial of local mulatto Maurice Mays, who had been accused of murdering a white woman. The murder had sparked the Knoxville Riot of 1919, one of the city's worst racial incidents, in August of that year. Mays was eventually found guilty and executed, though there was virtually no evidence linking him to the crime.[3]

See also

[edit]- Charles W. Cansler

- Cal Johnson

- James Herman Robinson

- Edward Terry Sanford

- Oliver Perry Temple

- List of first minority male lawyers and judges in Tennessee

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Robert Booker, William Francis Yardley, Tennessee State University Digital Library. Retrieved: 1 November 2012.

- ^ Knox Heritage, Fragile Fifteen, No. 14: Odd Fellows Cemetery. Retrieved: 5 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lewis Laska, William F. Yardley, Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2009. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ a b c East Tennessee Historical Society, Mary Rothrock (ed.), The French Broad-Holston Country: A History of Knox County, Tennessee (Knoxville, Tenn.: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1972), pp. 324-325.

- ^ East Tennessee Historical Society, Lucile Deaderick (ed.), Heart of the Valley: A History of Knoxville, Tennessee (Knoxville, Tenn.: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1976), p. 41.

- ^ Appletons' Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events, Vol. 17 (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1877), p. 710.

External links

[edit]- City of Knoxville, et al., v. W. F. Yardley – case argued in 1918