Gas in Turkey

Natural gas supplies over a quarter of Turkey's energy.[2][3] The country consumes 50 to 60 billion cubic metres of this natural gas each year,[4][5] nearly all of which is imported. A large gas field in the Black Sea however started production in 2023.[6]

After the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine several European countries stopped buying Russian oil or gas, but Turkey's relations with Russia are good enough that it continues to buy both.[7][8] Turkey receives almost half of its gas from Russia.[5] As of 2023[update] wholesale gas is expensive and a large part of the import bill.

Households buy the most gas, followed by industry and power stations.[9] Over 80% of the population has access to gas,[10] and it supplies half the country's heating requirements.[4] As the state owned oil and gas wholesaler BOTAŞ has 80% of the gas market,[2]: 16 the government can and does subsidize residential and industrial gas consumers.[11] All industrial and commercial customers, and households using more than a certain amount of gas, can switch suppliers.[2]

History

[edit]

The General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration was formed in 1935, but very little gas was found.[13][14] The most efficient way of importing gas is by pipeline from nearby countries, and the first imports were from Russia in 1986, followed by Iran.[15] However the pipeline from Azerbaijan only started in 2007.[15]

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) was first imported from Algeria in 1994 and from Nigeria in 1999.[15] In the early 21st century gas consumption increased.[16]: 9 Between 2000 and 2020 the share of imported energy increased from just over 50% to 70%.[17]

In 2019, the European Council objected to Turkish drilling in the eastern Mediterranean.[18] In 2022 a gas shutoff by Iran caused problems for industry.[19] Some analysts say that Turkey does not have enough gas storage or alternative supplies to resist pressure, and that when Russia says it is closing a gas pipeline for maintenance (for example a 10-day shutdown of Bluestream in 2022 at 2 days notice) this is sometimes intended to apply political pressure.[20] In 2022 the increase in global gas prices increased the current account deficit as more gas was bought on the spot market.[12]: 15

Geopolitics

[edit]Unlike several European countries, which stopped buying or were cut off from Russian oil or gas, after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, relations with Russia are such that Turkey continues to buy both.[7][8] China and Turkey import the most gas from Russia.[21] It is said to sometimes be difficult for media in Turkey to report fully on energy geopolitics.[20] President Erdoğan said in 2022 that Turkey could not join sanctions on Russia because of import dependency.[22]

Turkey's state-owned oil and gas exploration and production company TPAO hopes to explore for oil and gas in Libyan waters:[23] a memorandum of understanding was agreed with Libya but later suspended by a Libyan court.[24] Turkey opposes some gas exploration by the Republic of Cyprus because of the Cyprus–Turkey maritime zones dispute.[25][26]

The Northern Iraq two rival parties Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) would have to agree for a new pipeline to take the shortest route, as it would come from wells in the part of the Kurdistan Region controlled by the PUK and pass through the part controlled by the KDP.[27] In 2022 the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps used missiles to strike a house belonging to Baz Karim Barzanji, a businessman working on a new pipeline, reportedly because he had met American and Israeli officials there.[28][29][30]

Impact and future

[edit]

The largest source of greenhouse gas emissions by Turkey is coal power, which emits about 1000 grams of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide for every kilowatt-hour of electricity generated. To generate the same amount of electricity gas emits less than coal, (371g in 2020[31]), but far more than solar at 30g to 60g. When gas is produced in Russia or Turkmenistan, however, methane leaks release a greenhouse gas.[32] But, as the international greenhouse gas inventory is based on where it is produced, this is accounted for in Russia's greenhouse gas emissions not Turkey's.

Turkey intends to increase the share of renewables and nuclear power in the national energy mix.[33] According to a May 2022 report from thinktank Ember, solar and wind saved 7 billion US dollars on gas imports in the preceding 12 months.[34] Some distribution companies are testing mixing up to 20% hydrogen with natural gas, so that eventually some of the gas distributed would be green hydrogen.[35][36]

Earthquakes can be a danger to pipelines.[37] In neighbouring Iran electrification, for example with heat pumps, away from gas has been suggested to improve earthquake resilience.[38]

Supply and demand

[edit]Supply

[edit]There are many sources of supply in the region and enough LNG import capacity in the country.[39]

In 2020 Fatih, one of five drillships belonging to state owned oil and gas company TPAO, discovered the Sakarya Gas Field under the Black Sea near where Romania has also found gas.[40] Before 2023, when production from this sweet gas field in the Black Sea started, almost all natural gas consumed in Turkey was imported.[41][42] South Akcakoca Sub-Basin (SASB) is a small gas field also in the Black Sea.[43] As well as drillships there are 2 seismic ships.[44] Turkish Black Sea reserves are estimated at a trillion cubic metres:[45] gas will be piped to Filyos for processing to make it suitable for the gas grid,[46] with peak production of 40 billion cubic metres (bcm) targeted for 2026.[47] Turkish Black Sea gas is expected to eventually meet almost a third of national gas demand,[48] with 15 billion cubic metres (bcm) annually by 2030.[49] According to some commentators, with this discovery, the Aegean dispute with Greece over exploratory drilling is now unnecessary.[50]

Almost half of the country's gas is imported from Russia.[5] Turkey's long-term contracts with Russia are due to expire at the end of 2024,[51] and the natural gas import bill is expected to fall during the late 2020s due to the start of production from Turkey's part of the Black Sea.[52] In 2021 contracts with Russian energy company Gazprom were renewed and linked to the EU price;[53] they included a four-year deal to the end of 2025 for 5.75 bcm a year through TurkStream (which has total capacity 31.5 bcm).[54] The contract price has not been published but was reported (in 2022 by media opposed to the Turkish ruling parties) to be based on 70% of the LNG spot market price plus the Brent Crude oil price: this is much more expensive than the Blue Stream gas.[55]

US sanctions on Iran do not apply to pipeline imports of gas.[2]: 139 LNG import share varies but typically about a quarter of gas imports are LNG.[12] Total spot import was 6.9 bcm in 2021: spot can also be imported by pipeline.[44] Total entry capacity in 2021 was 362 mcm/day.[44] BOTAŞ would like to import from Northern Iraq, but completing the Iraqi part of the pipeline is mired in disputes between the Iraq central government and Kurdistan Regional Government.[56] However some gas in Iraq is wasted by flaring so Iraq would benefit by selling that.[57] Turkey suspects winter cuts in long-term low-price contracted supply from Iran are not technical faults but Iran keeping the gas for its own use.[56]

In 2021 a contract was agreed with Azerbaijan to import 11 bcm more per year until the end of 2024.[58] TPAO has a 19% share in Shah Deniz 1.[59] Fracking shale gas might help with energy security.[60] Gas supply from Turkmenistan has been planned for decades but a pipeline under the Caspian Sea has not yet been built,[61][62] partly due to lack of an agreement between Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan.[63] Turkmenistan is sending more gas to China.[64] Transit via Iran is technically possible as there is spare pipeline capacity.[49] However this is said (by backers of a rival route between at sea installations) to be only 3 bcma.[65] LNG is imported from several countries including Egypt,[66] Algeria, Oman,[67] and the United States.[68]

Demand

[edit]Over 80% of the population, and all provinces in Turkey, have access to natural gas,[10] which supplies half of household final energy.[69] In 2021 consumption share included 27% households, 35% electricity production, 29% industry and 8% service sector.[44] The Energy Ministry expects demand for gas to increase slightly to 2030, but its share of primary energy consumption to fall slightly to less than a quarter.[70]: 19–20

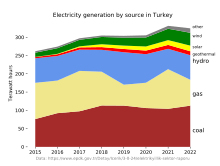

In some years electricity generation in Turkey burns half the gas, but this varies greatly depending on whether there is enough rain to produce hydroelectricity; therefore, when it rains, Turkey burns less gas.[2]: 139 Peak demand is typically in mid-winter, averaging almost 300 million cubic metres (mcm) each day,[44] and the Chamber of Engineers said in 2022 that there was not enough storage.[71] There are 72 distribution zones and 18 million households are supplied with gas.[44] About half of residential energy demand is met by gas.[2]: 139 The International Energy Agency predicted in 2021 that use for electricity generation will decline.[2]: 140 However the national energy plan published in January 2023 forecasts over 10 GW more gas power may be needed by 2035 to balance variable renewable energy and for energy security.[70]: 15–16 All industrial and commercial consumers, and households buying over 75 thousand cubic-meters a year can switch suppliers.[2]

Transport, processing and storage

[edit]

There are many gas pipelines,[66][75] and it may not be possible for Europeans to determine the origin of the gas they buy from Turkey.[76] Major gas pipelines (with capacity in bcm) are:

| ← | Out to west | Through | ← | In from east | ← |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | Trans-Balkan | Trans-Anatolian | 16 | TurkStream | 32 |

| 16 | Balkan Stream | Blue Stream | 16 | ||

| 10 | Trans Adriatic | South Caucasus | 24 | ||

| Tabriz Ankara | 14 |

Gas from Russia comes via the Blue Stream and TurkStream pipelines; and from Iran via the Tabriz–Ankara pipeline.[77] Azerbaijan normally supplies Turkey through the South Caucasus Pipeline. Its gas flows onward through the Trans-Anatolian gas pipeline (TANAP) supplying Turkey and some continues across the Greek border into the Trans Adriatic Pipeline.[78]

The Tabriz–Ankara pipeline is a 2,600-kilometre (1,600-mile) natural gas pipeline, which runs from Tabriz in northwestern Iran to Ankara in Turkey. Blue Stream, a major trans-Black Sea pipeline, has been delivering natural gas from Russia to Turkey since 2003.[79] The Southern Gas Corridor includes the Shah Deniz 2 gas field, the South Caucasus pipeline, TANAP, and the Trans Adriatic Pipeline: TANAP is being expanded to 31 bcm per year.[80] In Erzurum, the South Caucasus Pipeline, which was commissioned in 2006, is linked to the Iran-Turkey pipeline. In 2022 Turkey's transit pipeline had 3 to 5 bcm spare capacity.[81] As gas imports cost $12 to $15 billion per year and the lira is weak;[82] they are a significant part of the import bill.[83] Turkstream has about 60% spare capacity as of 2022.[84]

LNG can transit to Bulgaria, but there have been complaints that the deal is against EU free market rules.[85][86] Energy analysts doubt that Turkey will ever become a major gas transit country, and expect only Azeri gas transit to be significant.[87] However a few European countries, such as Serbia and Hungary, import Russian gas via Turkstream.[88] In 2021 Hungary's MVM Group and Gazprom signed a 15-year contract for 3.5 bcm to be supplied via Turk Stream and the Transbalkans pipeline, and in 2022 Hungary agreed 0.7 bcm per year more gas from Russia via Turk Stream.[89] In 2022 about 2 bcm from Turkstream was sent to Romania through the Trans-Balkan pipeline,[65] and exports to Moldova are starting in 2023.[90] Export to Ukraine through the Transbalkan has been technically possible since 2022,[91] and has been discussed between the 2 governments,[92] although Ukraine may be able to produce enough gas for its own needs.[93][94] The Turkey Bulgaria interconnector at 3.5 bcm a year may become a bottleneck.[95]

Black Sea gas is processed at Filyos. Marmara Ereğlisi is a major LNG terminal,[96] and the other two are Egegaz Aliağa LNG Storage Facility and Etki Liman LNG Facility.[12] In 2023 Turkey has 5 LNG terminals including the floating storage regasification units (FSRU)[12] MT Botaş FSRU Ertuğrul Gazi and Botaş Saros FSRU Terminal. FSRU may supply Bulgaria in future.[97] In addition to the existing storage of about 1 bcm at those five terminals, there is a goal to almost double the 2022 Silivri and Lake Tuz storage to total 10 bcm.[12]: 16

Economics and consumption

[edit]

According to BOTAŞ the price of gas for Turkish households was the lowest in Europe in 2022,[99] and they said residential customers were getting 70% price support from the government.[100] There are 72 gas distribution companies, with over 13 million consumers.[101] There is a biennial trade fair in Istanbul.[102]

Both national gas development and BOTAŞ are subsidised by the government.[103] In 2021 households were subsidized 80 billion lira ($7 billion) for gas - about 4 times their electricity subsidy.[104] Gas imports deplete foreign exchange reserves[105] and many analysts say that imported oil and gas is a key weakness in the economy of Turkey.[106] The country would like to become a hub to supply the EU,[107] however EU gas consumption is expected to decrease, so analyst Kadri Tastan says this is unlikely in the long term due to the EU green transition.[108] Although already somewhat of a physical hub for gas, Turkey cannot become a trading hub as the market, which is operated by Energy Exchange Istanbul, is not a free market.[109]

As of 2021[update] the annual gas import bill was around US$44 billion.[110] But long-term contracts with Russia and Iran will expire in the 2020s.[111] The contract to import from Iran expires in 2026.[112] Private companies are not allowed to enter into new pipeline gas contracts with countries that have contracts with the state owned oil and gas wholesaler BOTAŞ.[2] Although private companies can contract for LNG[2] they cannot buy at the same price as BOTAŞ.[113] Some imports from Russia are linked to the oil price, for example the BOTAŞ contract for import via Blue Stream, which expires at the end of 2025.[111] Solar and wind power are much cheaper than gas power.[114] Gas prices for industry and power plants are more than double the household price,[115] and are often increased due to falls in value of the lira.[116] In 2022 BOTAŞ borrowed from Deutsche Bank to buy LNG.[117]

In 2023 Vitaly Yermakov, Senior Research Fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies wrote: "Until 2022 Gazprom sales to Turkey were subject to oil-indexation, but at the end of 2021 this was replaced by hub indexation. (Turkey insisted on the change hoping it would receive lower prices, probably in reference to 2020, but has been shocked by the tremendous gas hub price spikes through the end of 2021 and into 2022 and 2023. Turkey has since asked Gazprom for a postponement of payments and begged for discounts)."[89] He also said that Turkey's negotiating power with Russia for gas discounts is greater than it was before the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.[89]: 15 A quarter of Russian gas is paid for in rubles.[118] In late 2022 Turkey was reported to have asked Russia for a discount on gas,[119] but prices are expected to remain high until the end of 2024[120] or 2026, with the 2023 price estimated by Bloomberg at around 500 USD per thousand cubic metres (compared to 300 for Russian sales to China) only slightly falling to 2026.[121] In 2024 the Energy Ministry said there were 357 gas-fired power stations in Turkey.

Subsidies and taxes

[edit]The wholesale gas market is not as competitive in Turkey as it is in the EU: some analysts say that this is because the government does not want to split up the state-owned gas company BOTAŞ, or give other power companies fair use of BOTAŞ' pipelines.[122] They say Turkey has not joined the European gas network (ENTSO-G) because joining would require this unbundling.[122] BOTAŞ controls over 90% of the natural gas market,[123] and is the gas infrastructure regulator and the only operator of gas transmission.[124] Exploration for gas in the Eastern Mediterranean is subsidised,[125][126] and is a cause of geopolitical tension because of the Cyprus dispute.[127]

A capacity market (or capacity mechanism) for electricity is payments to make sure that sufficient firm power is available to satisfy peaks in demand, such as late afternoon air conditioning in August. Because gas-fired power stations can usually ramp up and down quickly they are one way of ensuring supply at times of peak demand. Some other countries also have capacity markets but Turkey's has been criticised. The government says the purpose of capacity market payments is to secure national electricity supply.[128] However, despite almost all natural gas being imported, some gas-fired power plants received capacity payments in 2021, whereas some non-fossil firm power, such as demand response, could not.[128][129] 17 gas-fired power stations were eligible for capacity payments in 2023.[130]

Companies

[edit]Akfel Gas Group is state owned, and there are four private importers of gas.[20] Bosphorus Gaz, Bati Hat and Kibar Holding applied to import from Russia through the 6 bcm a year Trans-balkan pipeline in 2022, but the agreement for BOTAŞ to import gas through that pipeline ended that year.[131] Not all the 10 bcm contracted from Russia is actually flowing, possibly due to debts due to Gazprom by the companies.[20] Only BOTAŞ is importing LNG.[132] In 2022 the Turkish Energy Minister said that Turkey and Algeria would create a joint oil and gas exploration company.[133]

References

[edit]- ^ Kulovic, Nermina (4 February 2022). "Turkish drillship wraps up all planned well tests on Black Sea gas field". Offshore Energy. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j IEA (March 2021). Turkey 2021 – Energy Policy Review (Technical report). International Energy Agency. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Energy consumption by source, Turkey". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ a b "A Cold Winter: Turkey and the Global Natural Gas Shortage". Centre for Economics and Foreign Policy Studies (Edam). 6 October 2021. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ a b c "Ukraine War Complicates Turkey's Gas Challenge". Energy Intelligence. 9 March 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ "Can Sakarya pave the way for Turkey's gas independence?". IHS Markit. 25 April 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ a b Bakheit, Nesreen; Imahashi, Rurika (9 June 2022). "China, India and Turkey to siphon more Russian oil ahead of EU ban". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ a b Dezem, Vanessa (28 June 2022). "EU Gas Swings as Russia-Turkey Flows Resume While Risks Loom". BNN Bloomberg. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ Ergur, Semih (5 June 2022). "Increasing Usage of Natural Gas in Turkey and Its Effect on Local Economy". Climate Scorecard. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ a b 2021 Natural Gas Distribution Sector Report (PDF). Natural Gas Distribution Companies Association of Turkey (GAZBİR) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Coskun, Orhan (31 March 2022). "Turkey may hike April industry, power plant gas prices more than 20% -sources". Reuters. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f 2022 energy outlook (PDF) (Report). Industrial Development Bank of Turkey. December 2022.

- ^ "Oil Production in Turkey". Petform. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ "History". General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration (Turkey). Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Kanapiyanova, Zhuldyz. "Turkey-Russia Energy Cooperation on Natural Gas". Eurasian Research Institute. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "Turkey - Oil and Gas". United States Energy Information Administration.

- ^ "Turkey is faced with a serious energy crisis, says engineers chamber". Bianet. 7 February 2022.

- ^ "Turkish drilling activities in the Eastern Mediterranean: Council adopts conclusions". Council of the European Union. 15 July 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Muhdan, Saglam (31 January 2022). "Iran's gas cut exposes Turkey's vulnerability to energy risks". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Turkey, Russia gas ties grow contentious amid Ukraine war". Al-Monitor. 28 July 2022. Archived from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Payments to Russia for fossil fuels since 24 February 2022". Russia Fossil Tracker. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ "Russia Ukraine conflict: France raises Russian sanctions-busting with Turkey". Al Arabiya. 6 September 2022.

- ^ Gupte, Eklavya (10 October 2022). "Libya-Turkey exploration deal to fuel long-standing political, regional rivalries". S & P Global. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Bechev, Dimitar (27 February 2023). "Facing tragedy, Turkey mends ties with Greece and Armenia". Al Jazeera.

- ^ "ExxonMobil, Qatar sign Cyprus gas deal despite Turkey opposition". France 24. 10 December 2021. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ Michele Kambas; Gavin Jones; Stephen Jewkes; Orhan Coskun (11 February 2018). "Turkish blockade of ship off Cyprus is out of Eni's control: CEO". Reuters.

- ^ Ismail, Amina; Dahan, Maha El (13 June 2022). "Analysis: Kurdish tensions stymie Iraqi region's gas export ambitions". Reuters. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ "Iran File: Iran and Turkey face off in Iraq". Critical Threats. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Wilkenfeld, Yoni (14 June 2022). "Iraq at a crossroads: Kurdish energy competition with Iran". GIS Reports. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Times of Israel Staff. "Iran bombed Iraq's Kurdish region over natural gas plan involving Israel – report". Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ "Türki̇ye Elektri̇k Üreti̇mi̇ Ve Elektri̇k Tüketi̇m Noktasi Emi̇syon Faktörleri̇ Bi̇lgi̇ Formu" [Turkish electricity production and consumption emission factors] (PDF). Energy Ministry (in Turkish). Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Harvey, Fiona (23 February 2022). "Oil and gas facilities could profit from plugging methane leaks, IEA says". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ "Türkye's International Energy Strategy". Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ "Turkey: Wind and solar saved $7 bn in 12 months". Ember. 24 May 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ "Turkey to blend green hydrogen into natural gas supply network for heating". Balkan Green Energy News. 27 July 2020. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ Sabadus, Aura (12 April 2021). "Turkey moves closer to hydrogen grid injections, outlines long-term roadmap". ICIS Explore. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ "Hatay'da depremin ardından doğal gaz boru hattı patladı" [After earthquake gas pipeline explodes]. Hürriyet (in Turkish). İhlas News Agency. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ Salimi, Mohammad; Faramarzi, Davoud; Hosseinian, Seyed Hossein; Gharehpetian, Gevork B. (2020). "Replacement of natural gas with electricity to improve seismic service resilience: An application to domestic energy utilities in Iran". Energy. 200: 117509. Bibcode:2020Ene...20017509S. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.117509. S2CID 216481523.

- ^ O'Byrne, David (12 July 2022). "Turkey looks to import gas from Turkmenistan, test exports to Bulgaria". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ Fielder, Jez (21 August 2020). "Turkey's Erdogan announces discovery of large natural gas reserve off its Black Sea coast". Euronews. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Natural Gas". Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Turkey pushes for first Black Sea gas this quarter [Gas in Transition]". www.naturalgasworld.com. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "First new gas production from Black Sea field slated for end of October". 6 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Investor's Guide For Natural Gas". Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources.

- ^ Esau, Iain (5 January 2023). "First gas from huge Turkey project set to flow this quarter". Upstream Online. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ "Turkey begins laying Black Sea natural gas pipeline". Hürriyet Daily News. 14 June 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ "Erdogan says Turkey will accelerate Black Sea gas production from Sakarya field". Al Arabiya English. 14 June 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "Turkey's Black Sea gas find to raise output to 25% of EU capacity". www.worldoil.com. 27 September 2021. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ a b O'Byrne, David (25 April 2022). "US becomes Turkey's second biggest gas supplier, but for how long?". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ "The Guardian view on Turkish-Greek relations: dangerous waters | Editorial". The Guardian. 6 September 2020. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ Turkstream Impact on Turkey's Economy and Energy Security (PDF) (Report). "Istanbul Economics" & "The Center for Economics and Foreign Policy" – EDAM. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ "Turkish Petroleum mulls partnerships for multi-billion Black Sea gas project". www.worldoil.com. 8 February 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ Matalucci, Sergio (30 March 2022). "Turkey targets Balkans and EU renewables markets". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ "Russia's Gazprom signs four-year gas deal with Turkey's Botas". Reuters. 6 January 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "Why does Turkey pay a higher price for Russian natural gas than necessary?". Turkish Minute. 29 April 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Iraqi Kurdish gas to Turkey? Easier said than done". Middle East Eye. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "PM Barzani discusses energy, education, migration with PM Johnson". Rudaw. 20 April 2022.

- ^ "Turkey seals 11 bcm Azeri gas deal and making progress on supply, minister says". Reuters. 15 October 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Gas supplies from Azerbaijan's offshore Shah Deniz deposit to Turkiye to be suspended in August". Azernews. 27 July 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Yılankırkan, Nazile (30 June 2020). "Shale Gases, Potential and Impacts". Journal of Amasya University the Institute of Sciences and Technology. 1 (1). Sivas Cumhuriyet University Faculty of Technology, Mechatronics Engineering Department: 37–46.

- ^ O'Byrne, David (1 December 2021). "New American company seeks to realize Trans-Caspian pipe dream". Eurasianet. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Turkmenistan and Turkey to Collaborate on Export of Natural Gas to Europe - the Times of Central Asia". 4 March 2024.

- ^ O'Byrne, David (17 March 2022). "No magic tap for Europe to replace Russian gas via Turkey". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "China's Xi calls for greater cooperation with Turkmenistan on natural gas". Reuters. 6 January 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ a b Roberts, John; Bowden, Julian (12 December 2022). "Europe and the Caspian: The gas supply conundrum". Atlantic Council. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ a b Elliott, Stuart; O'Byrne, David (9 December 2021). "Egypt emerges as key LNG supplier to Turkey in Q4". S & P Global. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Oman LNG Inks 10-Year Gas Supply Deal with Turkey's Botas Petroleum". www.chemanalyst.com. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ "Turkey signs LNG deal with US supermajor ExxonMobil placing question mark over Russian gas supplies". www.intellinews.com. 9 May 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ "Natural gas dominates home energy use in Türkiye, survey finds - [İLKHA] Ilke News Agency". ilkha.com. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ a b Türkiye national energy plan (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. 2022.

- ^ "Turkey is faced with a serious energy crisis, says engineers chamber".

- ^ "Hungary's new gas deal fuels Russia fears". POLITICO. 2 April 2024. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Siccardi, Francesco. "Understanding the Energy Drivers of Turkey's Foreign Policy".

- ^ O'Byrne, David (22 November 2022). "Azerbaijan's Russian gas deal raises uncomfortable questions for Europe". Eurasianet. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ "Doğalgaz ve Petrol Boru Hatları Haritası" [Map of gas and oil pipelines]. Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources.

- ^ "Europe's Solidarity Gas Promises Disunity". 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Blast Halts Iran's Gas Exports To Turkey". Eurasia Review. Tasnim News. 31 March 2020. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Jansen, Gerald (17 May 2021). "Russia Is Making A Comeback In This Growing Gas Market". OilPrice.com. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ "Blue Stream at a glance: 15 yrs. of nonstop gas flow". Anadolu Agency. 28 February 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ "Turkey offers 'alternative' as energy hub for Europe". Hürriyet Daily News. 28 March 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ O'Byrne, David (6 May 2022). "Southeast Europe looks to Azerbaijan to replace Russian gas". Eurasianet. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ "Regional Solutions to Regional Challenges in the Middle East?". Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies. 30 November 2021. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "POLL Turkey's current account deficit at $4.1 bln in November; $48 billion in 2022". Reuters. 11 January 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Europe wary of Turkish hub to hide gas 'made in Moscow'". euronews. 1 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Bulgaria signs long-term agreement to use Turkish gas terminals". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ "Bulgaria-Turkey gas deal may break market principles – EFET". Hellenic Shipping News. 20 January 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Tastan, Kadri (2022). "Turkey and European Energy (In)Security". German Institute for International and Security Affairs. doi:10.18449/2022C38. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "Hungary in talks to redirect all Russian gas shipments to Turkstream". Reuters. 18 July 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Yermako, Vitaly (January 2023). ""Catch 2022" for Russian gas: plenty of capacity amid disappearing market Key Takeaways for Year 2022 and Beyond" (PDF). Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

- ^ "Turkey's BOTAS to begin supplying Moldova with natural gas from October".

- ^ Sabadus, Aura. "Moldova, Ukraine backhaul to unlock Trans-Balkan gas corridor". ICIS Explore. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine, Turkey discuss gas supplies through Trans-Balkan Corridor". www.ukrinform.net. 4 February 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ Brennan, David (27 September 2023). "Ukraine gives reason for allowing Russian gas transit despite war". Newsweek. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ Polityuk, Pavel; Harmash, Olena (22 September 2023). "Exclusive: Ukraine's natural gas consumption slumps due to war, Naftogaz CEO says". Reuters. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ "Turkey Willing To Boost EU Gas Exports If Bloc Guarantees Demand". OilPrice.com. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ Energy, GlobalData (17 November 2022). "Turkey leads the Middle East's operational LNG regasification capacity". Offshore Technology. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Elliott, Stuart; O'Byrne, David (23 December 2022). "Bulgaria in talks to take 1 Bcm/year of capacity at Turkish LNG terminals: minister". S & P Global. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "Turkey: A new emerging gas player with resources and infrastructure". Middle East Institute. Archived from the original on 19 June 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ "Turkey further raises natural gas prices, says still provides 'cheapest gas in Europe'". Bianet. 1 April 2022.

- ^ "Doğalgaza konutlarda %35, elektrik üretiminde %44,3 sanayide %50 zam" [35% increase in natural gas in homes, 44.3% increase in electricity production and 50% increase in industry]. BBC News Türkçe (in Turkish). 1 April 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ "Natural Gas Distribution". Natural Gas Distribution Companies Association of Turkey (GAZBIR). Archived from the original on 10 June 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ "Petroleum Istanbul 2023". PetrolPlaza. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Coskun, Orhan; Caglayan, Ceyda (15 April 2022). "Soaring costs put Turkey's energy importer under pressure to hike prices". Reuters. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "Turkey to produce 'sweet' natural gas, says minister". Hürriyet Daily News. 28 December 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ "Turkey strikes energy milestone as wind power output surges". TRT World. 1 December 2021. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ Wallace, Joe (29 November 2021). "Turkey's Lira Crisis Exposes Reliance on Imported Energy". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Can Turkey benefit from Europe's quest to reduce Russian gas?". Al-Monitor. 9 March 2022. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "Decarbonising EU-Turkey Energy Cooperation: Challenges and Prospects". German Institute for International and Security Affairs. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ O'Byrne, David (17 October 2022). "Putin's 'gas hub' plan aims to bolster Erdogan's image". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ Widdershoven, Cyril (12 June 2021). "Turkey makes moves to become an Energy Hub". OilPrice.com. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ a b Rzayeva, Gulmira (2018). Gas Supply Changes in Turkey (PDF) (Report). Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "Iran's share in Turkey's future gas market". Tehran Times. 28 September 2020. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus emergency measures should persuade Ukraine, Romania, and Turkey to legitimize energy reform, not reverse it". Atlantic Council. 18 May 2020. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ "Turkey: Wind and solar saved $7 bn in 12 months". Ember. 24 May 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ "Botaş hikes natural gas prices 20 pct". Hürriyet Daily News. 3 December 2021. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Gas price used in electricity production raised". Hürriyet Daily News. 2 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ "Turkey Gets Landmark $929 Million Deutsche Bank Loan to Buy LNG". Bloomberg News. 13 July 2022. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "Turkey to pay for some Russian gas in rubles". Deutsche Welle. 6 August 2022. Archived from the original on 9 January 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ "Turkey set to pay for 25 percent of Russian gas in roubles, says Putin". Ahval. 16 September 2022.

- ^ "Türkiye energy independence only comes with clean". Ember. 4 October 2022. Archived from the original on 14 February 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Rosen, Phil. "Russia will sell natural gas to China at almost a 50% discount compared to European buyers". Markets Insider. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ a b "A New Strategy for EU-Turkey Energy Cooperation". Turkish Policy Quarterly. 27 November 2018. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ DifiglioGürayMerdan (2020), p. 313.

- ^ DifiglioGürayMerdan (2020), p. 312.

- ^ "Turkey to continue gas drilling work around Cyprus: Foreign minister". Anadolu Agency. 16 October 2018. Archived from the original on 22 January 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "Fossil Fuel Support – TUR" Archived 31 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, OECD, accessed August 2018.

- ^ Lawless, Ghislaine (24 February 2020). "What lies beneath: gas-pricing disputes and recent events in Southern Europe". Arbitration Blog. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Elektri̇k Pi̇yasası Kapasi̇te Mekani̇zması Yönetmeli̇ği̇" [Electricity Market Capacity Mechanism Regulation: Article 1 and Article 6 clause 2) h)]. Resmî Gazete (30307). 20 January 2018.

- ^ "2021 Yılı Kapasite Mekanizmasından Yararlanacak Santraller Listesi" [Power stations benefiting from the capacity mechanism in 2021]. Turkish Electricity Transmission Corporation. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "2023'de 50 santral kapasite mekanizmasından yararlanacak" [TEİAŞ announces the 50 power plants to benefit from the capacity mechanism in 2023]. Enerji Günlüğü (in Turkish). 3 November 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ Byrne, David O. (13 August 2012). "Three companies have contracts with Gazprom to import gas to Turkey: official". S & P Global. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "Market sceptical of Bulgaria-Turkey gas agreement". Argus Media. 26 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Tastekin, Fehim (15 November 2022). "Turkey eyes risky energy partnership with Algeria". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Difiglio, Prof. Carmine; Güray, Bora Şekip; Merdan, Ersin (November 2020). Turkey Energy Outlook. iicec.sabanciuniv.edu (Report). Sabanci University Istanbul International Center for Energy and Climate (IICEC). ISBN 978-605-70031-9-5.