Samma dynasty

24°44′46.02″N 67°55′27.61″E / 24.7461167°N 67.9243361°E

Samma dynasty (Sindh Sultanate) سما راڄ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1351–1524 | |||||||||

Location of the Sammas, and main South Asian polities in 1400 CE[1] | |||||||||

| Status | Tributary to the Delhi Sultanate[2][3] | ||||||||

| Capital | Thatta | ||||||||

| Common languages | Sindhi • Kutchi • Gujarati in Halar • Arabic (liturgical language) | ||||||||

| Religion | Islam • Hinduism[4][5] | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Jam | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Samma dynasty begins | 1351 | ||||||||

• Samma dynasty ends | 1524 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Pakistan India[6] | ||||||||

The Samma dynasty (Sindhi: سمن جو راڄ, lit. 'Rule of the Sammas') was a medieval Sindhi[5][6][7] dynasty which ruled the Sindh Sultanate from 1351 before being replaced by the Arghun dynasty in 1524.

The Samma dynasty has left its mark in Sindh with structures including the necropolis of and royalties in Thatta.[5][8]

Beginnings

According to Chachnama, Jats of Lohana tribe included Sammas.[9] Sarah Ansari states both Sammas and Soomros to be Rajput tribes when they converted to Islam. Their chiefs were followers of Suhrawardi Sufi saints with their base at Uch and Multan.[10] Firishta mentions two groups of zamindars in Sindh, namely Sumra and Samma.[11]

Information about the early years of the Samma dynasty is very sketchy. Tribes such as Samma were regarded as a sub-division of Jats or on a par with the Jats when Muslims first arrived in Sindh,[12] and it is known from Ibn Battuta that in 1333 the Sammas were in rebellion, led by the founder of the dynasty, Jam Tamachi Unar.[citation needed] The Sammas overthrew the Soomras soon after 1335 and the last Soomra ruler took shelter with the governor of Gujarat, under the protection of Muhammad bin Tughluq, the sultan of Delhi.[citation needed] Mohammad bin Tughlaq made an expedition against Sindh in 1351 and died at Sondha, possibly in an attempt to restore the Soomras. With this, the Sammas became independent.[citation needed] The next sultan, Firuz Shah Tughlaq attacked Sindh in 1365 and 1367, unsuccessfully, but with reinforcements from Delhi he later obtained Banbhiniyo's surrender. The Samma dynasty overtook the Sumra dynasty and ruled Sindh during 1365–1521. Around that time, the Sindhi Swarankar community returned from Kutch to their home towns in Sindh, and some settled empty land on the banks of Sindhu River near Dadu, Sindh. By the end of year 1500, nearly the entire Sindhi Swarankar community had returned to Sindh. This period marks the beginning of Sufistic thought and teachings in Sindh.[citation needed]

For a period the Sammas were therefore subject to Delhi again. Later, as the Sultanate of Delhi collapsed they became fully independent.[13] During most of period of Samma rule, the Sindh was politically and economically tied to the Gujarat Sultanate, with occasional periods of friction. Coins struck by the Samma dynasty show the titles "Sultan" and "Shah" as well as "Jam", the Jadeja rulers of western Gujarat also part of Samma tribe and directly descended from Jam Unar, the first Samma sultan of Sindh.[14] Sandhai Muslims are Samma of Sindh. Even the Chudasama Rajputs of Gujarat are also part of Samma tribe, who are still Hindu, and distributed in Junagadh District and Bhal Region of Gujarat.[15][16]

History

| Sultans of Sindh Samma Dynasty "History of Delhi Sultanate" by M. H. Syed |

|

The Samma dynasty took the title "Jam", the equivalent of "King" or "Sultan", because they claimed to be descended from Jamshid.[17] The main sources of information on the Samma dynasty are Nizammud-din, Abu-'l-Fazl, Firishta and Mir Ma'sum, all lacking in detail, and with conflicting information. A plausible reconstruction of the chronology is given in the History of Delhi Sultanate by M. H. Syed.[17]

Jam Unar

Jam Unar was the founder of Samma dynasty mentioned by Ibn Battuta, the famous traveller from North Africa (Ibn Battuta visited Sindh in 1333, and saw Samma's rebellion against Delhi government[13]). Jam Unar, the Samma chief, taking advantage of the strained relation between the Soomra and the Sultanate of Delhi, defeated the last Soomra ruler, son of Dodo, and established Samma rule.[citation needed]

Jam Salahuddin

Jám Saláhuddìn bin Jám Tamáchí was the successor of his father Jám Tamáchí. He put down revolts in some parts of the country, by sending forces in those directions and punished the ringleaders. Some of these unruly bands fled to Kachh, to which place Jám Saláhuddín pursued them, and in every engagement that took place he defeated them and ultimately subjugated them. He died after a reign of 11 years.[citation needed]

Jam Ali Sher

Jám Alí Sher bin Jám Tamáchí ruled the country very discreetly. Tamáchí's other sons Sikandar and Karn, and Fateh Khán son of Sikandar, who had brought ruin on the last Jám, were now conspiring against Jám Alísher. They were therefore looking for an opportunity to fall upon him while he was out enjoying the moonlight as usual. They spent their time in the forests in the vicinity of the town. One Friday night, on the 13th of the lunar month, they took a band of cut-throats with them, and with naked swords attacked Jám Alísher who had come out in a boat to enjoy the moonlight on the quiet surface of the river and was returning home. They killed him, and red-handed they ran to the city, where the people had no help for it but to place one of them, Karan, on the vacant throne. The reign of Jám Alí Sher lasted for seven years.[citation needed]

Jam Fateh Khan bin Jam Sikandar

Jám Karan was succeeded by his nephew Jám Fateh Khán bin Sikandar. He ruled quietly for some time and gave satisfaction to the people in general.[citation needed]

About this time, Mirza Pir Muhammad one of Amir Timur’s grandsons came to Multan and conquered that town and Uch. As he made a long stay there, most of the horses with him died of a disease and his horsemen were obliged to move about as foot-soldiers. When Amir Timur heard of this, he sent 30,000 horses from his own stables to his grandson to enable him to extend his conquests. Pir Muhammad, being thus equipped, attacked those of the zamindars who had threatened to do him harm and destroyed their household property. He then sent a messenger to Bakhar calling the chief men of the place to come and pay respects to him. But these men fearing his vengeance left the place in a body and went to Jesalmer. Only one solitary person, Sayyed Abulghais, one of the pious Sayyeds of the place, went to visit the Mirzá. He interceded for his town-people in the name of his great grandfather, the Prophet, and the Mirzá accepted his intercession.[citation needed]

Mirzá Pír Muhammad soon went to Delhi, which place he took and where he was crowned as king. Multan remained in the hands of Langáhs, and Sind in those of the Sammah rulers as before.[citation needed]

Jam Taghlak

Jám Taghlak was fond of hunting and left his brothers to administer the affairs of state at Sehwán and Bakhar. In his reign some Balóch raised the standard of revolt in the outskirts of Bakhar, but Jám Taghlak marched in the direction and punished their ring-leaders and appointed an outpost in each parganah to prevent any future rebellion of the kind. He died after a reign of 28 years.[citation needed]

Jam Sikandar

Jám Sikandar bin Jám Taghlak was a minor when he succeeded his father to the throne. The governors of Sehwán and Bakhar shook off their yoke, and prepared to take offensive steps. Jám Sikandar was obliged to march out from Tattá to Bakhar. When he came as far as Nasarpúr, a man by name Mubárak, who during the last Jám's reign had made himself celebrated for acts of bravery, proclaimed himself king under the name of Jám Mubárak. But as the people were not in league with him, he was driven away within 3 days and information sent to Jám Sikandar, who made peace with his opponents and hastened to Tattá. After a year and a half, he died.[citation needed]

Jam Nizamuddin I

After Jam Salahuddin's death, the nobles of the state put his son Jám Nizámuddín I bin Jám Saláhuddín on the throne. Jam Nizamuddin ruled for only a few months. His first act of kindness was the release of his cousins Sikandar, Karn and Baháuddín and Ámar, who had been placed in captivity by the advice of the ministers. He appointed every one of them as an officer to discharge administrative duties in different places, while he himself remained in the capital, superintending the work done by them and other officials in different quarters of the country.[citation needed]

Before long, however, his cousins, very ungratefully made a conspiracy among themselves and stealthily coming to the capital attempted to seize him. But Jám Saláhuddín learning their intention in time, left the place at the dead of night with a handful of men and made his escape to Gujrat. In the morning, men were sent after him, but before any information could be brought about him, the people summoned Alísher, son of Jám Tamáchí, who was living in obscurity, and raised him to the throne. Meanwhile, Jám Nizámuddín also died in his flight and his cousins too being disappointed in every thing, lived roving lives.[citation needed]

Jam Sanjar

On Ráinah's death, Sanjar (Radhan) Sadr al-Din became the Jám of Sind. He is said to have been a very handsome person, and on that account was constantly attended by a large number of persons, who took pleasure in remaining in his company. It is believed that before his coming to the throne, a pious fakír had been very fond of him; that one day Sanjar informed him that he had a very strong desire to become the king of Tattá though it should be for not more than 8 days; and that the fakír had given him his blessings, telling him that he would be the king of the place for 8 years.[citation needed]

Jám Sanjar ruled the country very wisely. Under no ruler before this had the people of Sind enjoyed such ease of mind. He was very fond of the company of the learned and the pious. Every Friday he used to distribute charities and had fixed periodical allowances for those who deserved the same. He increased the pay of responsible officers. One Kází Maarúf, who had been appointed by the late rulers to be the Kází of Bakhar, was in the habit of receiving bribes from the plaintiffs as well as from the defendants. When this fact came to the notice of Jám Sanjar, he sent for the Kází and asked him about it.[citation needed] The Kází admitted the whole thing. "Yes", said he, "I do demand something from the plaintiffs as well as the defendants, and I am anxious to get something from the witnesses too, but before the case closes, they go away and I am disappointed in that". Jám Sanjar could not help laughing at this. The Kází continued: "I work in the court for the whole day and my wife and children die of hunger at home, because I get very little pay". Jám Sanjar increased his pay and issued general orders for the increase of every government post of importance.[citation needed]

Jam Nizamuddin II

Jám Nizámuddín II (866–914 AH, 1461–1508 AD) was the most famous Sultan of the Samma or Jamot dynasty,[19] which ruled in Sindh and parts of Punjab and Balochistan (region) from 1351–1551 CE. He was known by the nickname of Jám Nindó. His capital was at Thatta in modern Pakistan. The Samma Sultanate reached the height of its power during the reign of Jam Nizamuddin II, who is still recalled as a hero, and his rule as a golden age.[citation needed]

Shortly after his accession, he went with a large force to Bhakkar, where he spent about a year, during which time he extirpated the freebooters and robbers who annoyed the people in that part of the country. After that, for a period of forty-eight years he reigned at Tatta with absolute power.[citation needed]

In the last part of Jám Nindó's reign, after 1490 CE, a Mughul army under Shah Beg Arghun came from Kandahar and fell upon many villages of Chundooha and Sideejuh, invading the town of Ágrí, Ohándukah, Sibi Sindichah and Kót Máchián. Jám Nindó sent a large army under his Vazier Darya Khan,[20] which, arriving at the village known by the name of Duruh-i-Kureeb, also known as Joolow Geer or Halúkhar near Sibi, defeated the Mughuls in a pitched battle. Sháh Beg Arghun's brother Abú Muhammad Mirzá was killed in the battle, and the Mughuls fled back to Kandahár, never to return during the reign of Jám Nizámuddín.[21]

Jam Nizamuddin's death was followed by a war of succession between the cousins Jam Feroz and Jam Salahuddin.[citation needed]

Jam Feruzudin

Jam Feruz bin Jam Nizam was the last ruler of the Samma dynasty of Sindh. Jám Feróz succeeded his father Jám Nizámuddín at a minor age. Jám Feróz was a young man, and as from the commencement the management of the state affairs was in the hands of his guardian he spent his time in his harem and seldom went out. But he was fearful of his ministers.[citation needed]

As a precautionary measure he enlisted in his service Kíbak Arghún and a large number of men belonging to the tribes of Mughuls, who had during his reign, left Sháhbeg Arghún and came to Tattá. Jám Feróz gave them the quarter of the town, called Mughal-Wárah to live in. He secretly flattered himself for his policy in securing the services of intrepid men to check Daryá Khán, but he never for a minute imagined what ruin these very men were destined to bring on him. For, it was through some of these men that Sháhbeg Arghún was induced to invade and conquer Sind in 926 AH (1519 AD) at the Battle of Fatehpur, which resulted in the displacement of the Sammah dynasty of rulers by that of Arghún.[citation needed]

Legacy

The rise of Thatta as an important commercial and cultural centre was directly related to Jam Ninda's patronage and policies. At the time the Portuguese took control of the trading centre of Hormuz in 1514 CE,[23] trade from the Sindh accounted for nearly 10% of their customs revenue, and they described Thatta as one of the richest cities in the world. Thatta's prosperity was based partly on its own high-quality cotton and silk textile industry, partly on export of goods from further inland in the Punjab and northern India. However, the trade declined when the Mughals took over. Later, due to silting of the main Indus channel, Thatta no longer functioned as a port.[24]

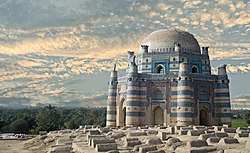

The Samma civilization contributed significantly to the evolution of the Indo-Islamic architectural style. Thatta is famous for its necropolis, which covers 10 square km on the Makli Hill. It assumed its quasi-sacred character during Jam Ninda's rule. Every year thousands perform pilgrimage to this site to commemorate the saints buried here. The graves testify to a long period when Thatta was a thriving center of trade, religion and scholarly pursuits.[25]

External links

See also

References

- ^ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 39, 147. ISBN 0226742210.

- ^ Naz, Humera (2019). "Sindh under the Mughals: Some Glimpses from Tarikh-i-Masumi and Mazhar-i- ShahjahaniI". Pakistan Perspectives. 24 (2). SSRN 3652107.

- ^ Sheikh, Samira (2010). Forging a Region Sultans, Traders, and Pilgrims in Gujarat, 1200–1500. Oxford University Press. p. 42. ISBN 9780199088799.

- ^ P. M. Holt; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis (21 April 1977). The Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 2A, The Indian Sub-Continent, South-East Asia, Africa and the Muslim West. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8.

- ^ a b c Census Organization (Pakistan); Abdul Latif (1976). Population Census of Pakistan, 1972: Larkana. Manager of Publications.

- ^ a b U. M. Chokshi; M. R. Trivedi (1989). Gujarat State Gazetteer. Director, Government Print., Stationery and Publications, Gujarat State. p. 274.

It was the conquest of Kutch by the Sindhi tribe of Sama Rajputs that marked the emergence of Kutch as a separate kingdom in the 14th century.

- ^ Rapson, Edward James; Haig, Sir Wolseley; Burn, Sir Richard; Dodwell, Henry (1965). The Cambridge History of India: Turks and Afghans, edited by W. Haig. Chand. p. 518.

- ^ Population Census of Pakistan, 1972: Jacobabad

- ^ Kalichbeg (1900). The Chachnamah An Ancient History Of Sindh.

- ^ Ansari, Sarah F. D. (1992-01-31). Sufi Saints and State Power: The Pirs of Sind, 1843-1947. Cambridge University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-521-40530-0.

One of the most well-known all-India examples of Suhrawardi intervention in political affairs concerned Sind. Between 1058 and 1520, control of the province was effectively delegated by the Delhi Sultanates first to the Soomros and later to the Sammas. Both were local Rajput tribes converted to Islam whose chiefs were disciples of Suhrawardi saints at Uch and Multan.

- ^ Sindh: Land of Hope and Glory. Har-Anand Publications. 2002. p. 112. ISBN 9788124108468. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ Wink, A. (2002). Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World. Early medieval India and the expansion of Islam 7th-11th centuries. Vol. 1. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 158-159. ISBN 978-0-391-04125-7. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

The Lohana, Lakha, Samma, Sahtah, Chand (Channa)....which appear, at least in the Muslim sources, to be subdivisions of the Jats or to be put on a par with the Jats. Some of these tribes were dominating others, but they all, as a matter of course, suffered certain discriminatory measures (cf. infra) under both the Rai and Brahman dynasties and the Arabs. The territories of the Lohana, Lakha and Samma are also described as separate jurisdictions under the governor of Brahmanabad in the pre-Muslim era. Whatever may be the original distinction between Samma and Jat - the two tribes from which the majority of Sindhis descend - , in later times it became completely blurred and the same people may be classed as Samma and Jat. The Samma residential area however was probably restricted to Brahmanabad and its immediate neighbourhood.

- ^ a b "Directions in the History and Archaeology of Sindh by M. H. Panhwar". Archived from the original on 2018-12-25. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- ^ Anjali H. Desai (2007). India Guide Gujarat. India Guide Publications. pp. 311–. ISBN 978-0-9789517-0-2.

- ^ Kumar Suresh Singh; Rajendra Behari Lal; Anthropological Survey of India (2003). Gujarat, Part 1 Gujarat, Anthropological Survey of India. Popular Prakashan. pp. 1174–1175. ISBN 9788179911044.

- ^ People of India Gujarat Volume XXII Part One edited by R.B Lal, S.V Padmanabham & A Mohideen page 1174-75 Popular Prakashan

- ^ a b [History of Delhi Sultanate by M.H. Syed (p240), 2005 ISBN 978-8-12611-830-4]

- ^ Ephrat, Daphna; Wolper, Ethel Sara; Pinto, Paulo G. (7 December 2020). Saintly Spheres and Islamic Landscapes: Emplacements of Spiritual Power across Time and Place. BRILL. p. 276. ISBN 978-90-04-44427-0.

- ^ The Hindu - The world's largest necropolis

- ^ The environments that led to the rise and fall of the Kalhoras

- ^ A HISTORY OF SIND, EMBRACING THE PERIOD FROM A.D. 710 TO A.D. 1590 by MAHOMED MASOOM;

- ^ Qureshi, Urooj (8 August 2014). "In Pakistan, imposing tombs that few have seen". BBC Travel. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 694.

- ^ [The Global World of Indian Merchants, 1750-1947: Traders of Sind from Bukhara to Panama by Claude Markovits, 2000 ISBN 978-0-521-62285-1]

- ^ Archnet.org: Thattah Archived 2012-06-06 at the Wayback Machine

Sources

- This article incorporates text from the work A History of Sind by Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg, a publication now in the public domain.

- Islamic culture - Page 429, by Islamic Culture Board

- The History and Culture of the Indian People - Page 224, by Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bhāratīya Itihāsa Samiti

- Searchlights on Baloches and Balochistan, by Mir Khuda Bakhsh Marri

- The Delhi Sultanate, by Kanaiyalal Maneklal Munshi, Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, Asoke Kumar Majumdar, A. D. Pusalker

- Babar, by Radhey Shyam

- Indo-Arab relations: an English rendering of Arab oʾ Hind ke taʾllugat, by Syed Sulaiman Nadvi, Sayyid Sulaimān Nadvī, M. Salahuddin

- Muslim Kingship in India, by Nagendra Kumar Singh

- The Indus Delta country: a memoir, chiefly on its ancient geography and history, by Malcolm Robert Haig

- The Samma kingdom of Sindh: historical studies, by G̲h̲ulāmu Muḥammadu Lākho, University of Sind. Institute of Sindology

External links

Media related to Samma dynasty at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Samma dynasty at Wikimedia Commons