Sufi literature

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

| |

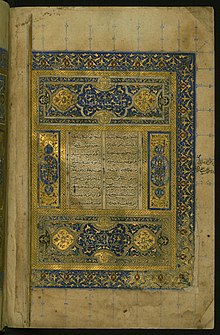

Sufi literature consists of works in various languages that express and advocate the ideas of Sufism.

Sufism had an important influence on medieval literature, especially poetry, that was written in Arabic, Persian, Turkic, Sindhi and Urdu. Sufi doctrines and organizations provided more freedom to literature than did the court poetry of the period. The Sufis borrowed elements of folklore in their literature.

The works of Nizami, Nava'i, Hafez, Sam'ani and Jami were more or less related to Sufism. The verse of such Sufi poets as Sanai (died c. 1140), Attar (born c. 1119), and Rumi (died 1273) protested against oppression with an emphasis on divine justice and criticized evil rulers, religious fanaticism and the greed and hypocrisy of the orthodox Muslim clergy. The poetic forms used by these writers were similar to the folk song, parable and fairy tale.

History

[edit]Sufi literature, written in Persian, flourished from the 12th to 15th centuries. Later, major poets linked with the Sufi tradition included Hatef Esfahani (17th century), Bedil (18th century), and Ahmad NikTalab (20th century). However, Sufi literature for the longest time in history had been scattered in different languages and geographic regions.[1][2] From the 19th and 20th centuries onwards, the historiography of Sufism, especially in the west, has been the meticulous collection of diverse sources and facts regarding the subject.[3] As compared to, say, broadly speaking, English or German literature, Sufi literature has been controversial because of the origin of Sufism itself as a tradition. Some scholars argue Sufism is a tendency within Islam whereas others argue that Sufism, as in the way of thinking, predates Islam. Radical Islamic scholars of an older generation, some even in contemporary times, dismiss the Sufi tradition as something that is purely mystical and therefore deny Sufism's spiritual lineage to Islam.[4] Their argument is Sufism comes in the way of recognising the true nature of Islam. Nevertheless, the process of accumulating data on Sufism by many European Orientalist scholars led to the birth of significant discourses within Sufi literature that dominated western thought on the subject for a long time. Even before the 19th century, as argued by Carl Ernst, some Orientalist scholars attempted to disassociate Sufi literature from Islam, based on positive and negative tendencies.[5] In his work, Ernst challenges such interpretations and those made by the colonial Orientalists and native fundamentalists.

Alexander D Knysh, a professor of Islamic studies at the University of Michigan, claims the first serious attempts to address Sufism in academic discourses can be traced back to the 17th century.[3] The discussions by scholars in the west around this time were concerned with critically analysing and translating the Sufi literature. Notably, the literary output of renowned Persian poets such as Sadi, Attar, Rumi, Jami, and Hafez. However, Knysch also points out a rather contrasting image of Sufism that appears within the personal memoirs and travelogues of western travellers in the Middle East and Central Asia in the 18th and 19th centuries. Mostly produced by western travellers, colonial administrators, and merchants, they perceived Sufi literature and the overall tradition as exotic, erratic behaviour, and strange practices by the dervishes.[3] In such works, literary concerns were mixed with a larger goal to illustrate a systematic and accurate account of various Sufi communities, practices, and doctrines.[3] Although such scholars were intrigued by the nature of Sufi literature and many of the individual Sufi dervishes, they were hesitant in considering the mystical elements of Sufism to be something inherent to the larger Islamic religion. This is because they did not consider Islam and Christianity in the same light and therefore considered Islam to be incapable of producing the kind of theological discussions present within Sufi literature.[3] For instance, Joseph Garcin de Tassy (1794–1878), a French Orientalist, translated and produced a large number of works on Islamic, Persian, and Hindustani discourses. He admired the Persian language and literature yet showed a conventional anti-Islamic prejudice notable of his time. He perceived Sufi literature vis-à-vis Christian heretics but considered the former as a distorted version of the latter. He thought Islamic cultures restrict human autonomy and material pleasures.[3] Such views on Sufi literature were commonly shared at the time by several European Orientalists who were originally trained as either philologists or Biblical studies scholars.[3]

Sufi poetry emerged as a form of mystical Islamic devotional literature that expresses themes such as divine love and the mystical union between man and God, often through the metaphors of secular love poetry. Over the centuries, non-mystical poetry has in turn made significant use of the Sufi vocabulary, producing a mystical-secular ambiguity in Persian, Turkish, and Urdu-language literatures.[6]

Themes

[edit]

The Sufi conception of love was introduced first by Rabia of Basra, a female mystic from the eighth century. Throughout Rumi's work the "death" and "love" appear as the dual aspects of Rumi's conception of self-knowledge. Love is understood to be "all-consuming" in the sense that it encompasses the whole personality of the lover. The influence of this tradition in Sufism was likely drawn from Persian or Hindu sources; no comparable idea is known from ninth century Christianity or Judaism. In a literary wordplay Fakhreddin Eraqi changed the words of the shahada (la ilaha illa'llah) to la ilaha illa'l-'ishq ("there is no deity save Love"). For his part, Rumi, in his writings, developed the concept of love as a direct manifestation of the will of God, in part as a calculated response to objections coming from the orthodox wing of Islam: "Not a single lover would seek union if the beloved were not seeking it".[7] The concepts of unity and oneness of mankind also appear in Rumi's works. For example, the poem "Who Am I?"[8]

Notable works

[edit]- The Mathnawī and Diwan-e Shams-e Tabriz-i of Rūmī

- Dīwān of Hāfez by Hafiz Shirazi

- Fuṣūṣ-ul-Ḥikam ("The Bezels of Wisdom") and Tarjumān al-Ashwāq ("The Interpreter of Desires") by Ibn Arabi

- Kimiya-yi sa'ādat ("The Alchemy of Happiness") by Al-Ghazali

- The Conference of the Birds by Farid al-Din Attar

- The Dīwān of Yūnūs by Yunus Emre

- The Qaṣīdat-ul-Burda ("Poem of the Mantle") of al-Buṣīrī

- Asrār-ut-Tawḥīd ("The Secrets of Unity") by Shaikh Abū Sa`īd Abū-l-Khair

- al-Fatḥ al-mubīn fī madḥ al-amīn ("Clear Inspiration, on Praise of the Trusted One") by ʿĀ’ishah bint Yūsuf al-Bāʿūniyyah

- Diwan-e-Akhtar by Hazrat Hakim Akhtar

- Dala’il al-Barakat by Muhammad Tahir ul-Qadri

- Kulliyyat-e-Hasrat by Muhammad Abdul Qadeer Siddiqi Qadri 'Hasrat'

- Lataife Ashrafi by Ashraf Jahangir Semnani

- Tassawwuff by Syed Waheed Ashraf

- The poems of Sultan Bahu

- Some poems of Ahmad NikTalab

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Melchert, Christopher (2015). The Cambridge companion to Sufism. Lloyd V. J. Ridgeon. New York, NY. pp. 3–23. ISBN 978-1-139-08759-9. OCLC 898273387.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Sufism in the West. Jamal Malik, John R. Hinnells. London: Routledge. 2006. pp. 32–37. ISBN 0-203-08720-8. OCLC 71148720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Knysh, Alexander (2005). A companion to the history of the Middle East. Youssef M. Choueiri. Malden, MA. pp. 108–119. ISBN 978-1-4051-0681-8. OCLC 57506558.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Introduction to Sufi Literature in North India". Sahapedia. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ Ernst, Carl. "Sufism, Islam, and Globalization in the Contemporary World: Methodological Reflections on a Changing Field of Study".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Sufi literature. Britannica. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Milani, Milad. Sufism in the Secret History of Persia. Routledge (2013), 36.

- ^ Aminrazavi, Mehdi (2015). Sufism and american literary masters. State Univ Of New York Pr. ISBN 978-1438453521. OCLC 908701099.

Further reading

[edit]- Salamah-Qudsi, Arin. (2020). "A New Study Model for Arabic Sufi Prose." Middle Eastern Literatures 23(1–2): 79–96. doi:10.1080/1475262X.2021.1878647

- Chopra, R. M. (1999). Great Sufi Poets of The Punjab. Iran Society, Calcutta.

- Chopra, R. M. (2016). Sufism (Origin, growth, eclipse, resurgence). Anuradha Prakashan, New Delhi. ISBN 978-93-85083-52-5.

External links

[edit] Media related to Sufi literature at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sufi literature at Wikimedia Commons