XLR-11

| |

| Legal status | |

|---|---|

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

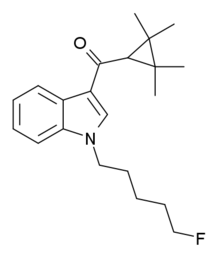

| Formula | C21H28FNO |

| Molar mass | 329.459 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

XLR-11 (5"-fluoro-UR-144 or 5F-UR-144) is a drug that acts as a potent agonist for the cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2 with EC50 values of 98 nM and 83 nM, respectively.[2] It is a 3-(tetramethylcyclopropylmethanoyl)indole derivative related to compounds such as UR-144, A-796,260 and A-834,735, but it is not specifically listed in the patent or scientific literature alongside these other similar compounds,[3][4] and appears to have not previously been made by Abbott Laboratories, despite falling within the claims of patent WO 2006/069196. XLR-11 was found to produce rapid, short-lived hypothermic effects in rats at doses of 3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, suggesting that it is of comparable potency to APICA and STS-135.[2]

Detection

[edit]A forensic standard for this compound is available, and a representative mass spectrum has been posted on Forendex.[5]

Recreational use

[edit]XLR-11 was instead first identified by laboratories in 2012 as an ingredient in synthetic cannabis smoking blends, and appears to be a novel compound invented specifically for grey-market recreational use.[6]

Legal Status

[edit]XLR-11 was banned in New Zealand by being added to the temporary class drug schedule, as of 13 July 2012[update].[7]

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) made XLR11 illegal under the Federal Controlled Substances act for the foreseeable future as of January 2024[update].[8]

It has also been banned in Florida as of 11 December 2012[update].[9]

Arizona banned XLR-11 on 3 April 2013.[10]

As of October 2015[update], XLR-11 is a controlled substance in China.[11]

XLR-11 is banned in the Czech Republic.[as of?][12]

Side effects

[edit]XLR-11 has been linked to hospitalizations due to its use.[13]

Toxicity

[edit]XLR-11 has been linked to acute kidney injury in some users,[14] along with AM-2201.[15][16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Anvisa (24 July 2023). "RDC Nº 804 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 25 July 2023). Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ a b Banister SD, Stuart J, Kevin RC, Edington A, Longworth M, Wilkinson SM, et al. (August 2015). "Effects of bioisosteric fluorine in synthetic cannabinoid designer drugs JWH-018, AM-2201, UR-144, XLR-11, PB-22, 5F-PB-22, APICA, and STS-135". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 6 (8): 1445–1458. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00107. PMID 25921407.

- ^ WO application 2006069196, Pace JM, Tietje K, Dart MJ, Meyer MD, "3-Cycloalkylcarbonyl indoles as cannabinoid receptor ligands", published 2006-06-29, assigned to Abbott Laboratories

- ^ Frost JM, Dart MJ, Tietje KR, Garrison TR, Grayson GK, Daza AV, et al. (January 2010). "Indol-3-ylcycloalkyl ketones: effects of N1 substituted indole side chain variations on CB(2) cannabinoid receptor activity". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 53 (1): 295–315. doi:10.1021/jm901214q. PMID 19921781.

- ^ "XLR-11". Structural, chemical, and analytical data on controlled substances. Southern Association of Forensic Scientists (SAFS).

- ^ Wilkinson SM, Banister SD, Kassiou M (2015). "Bioisosteric Fluorine in the Clandestine Design of Synthetic Cannabinoids". Australian Journal of Chemistry. 68: 4. doi:10.1071/CH14198.

- ^ "CB-13, MAM-2201, AKB48, and XLR11 are classified as temporary class drugs". Temporary Class Drug Notice. The Department of Internal Affairs: New Zealand Gazette. 5 July 2012.

- ^ DEA (April 2024). "Lists of: Scheduling Actions, Controlled Substances, Regulated Chemicals" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Attorney General Pam Bondi Outlaws Additional Synthetic Drugs" (Press release). State of Florida. 11 December 2012.

- ^ "Governor Jan Brewer Signs Legislation to Combat Production, Use of Dangerous Drugs" (PDF) (Press release). Office of the Governor, State of Arizona. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ^ "关于印发《非药用类麻醉药品和精神药品列管办法》的通知" (in Chinese). China Food and Drug Administration. 27 September 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ "Látky, o které byl doplněn seznam č. 4 psychotropních látek (příloha č. 4 k nařízení vlády č. 463/2013 Sb.)" (PDF) (in Czech). Ministerstvo zdravotnictví.

- ^ Trecki J, Gerona RR, Schwartz MD (July 2015). "Synthetic Cannabinoid-Related Illnesses and Deaths". The New England Journal of Medicine. 373 (2): 103–107. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1505328. PMID 26154784.

- ^ "Alphabet Soup, or the newer synthetic cannabinoids..." The Dose Makes The Poison Blog. 11 December 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Bhanushali GK, Jain G, Fatima H, Leisch LJ, Thornley-Brown D (April 2013). "AKI associated with synthetic cannabinoids: a case series". Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 8 (4): 523–526. doi:10.2215/CJN.05690612. PMC 3613952. PMID 23243266.

- ^ "Acute Kidney Injury Associated with Synthetic Cannabinoid Use – Multiple States, 2012". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 15 February 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2013.