Angkor Borei and Phnom Da

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Angkor Borei and Phnom Da | |

|---|---|

Asram Moha Russei temple in Angkor Borey site | |

| Location | Angkor Borei District, Takéo Province, of southern Cambodia |

| Coordinates | 10°59′42″N 104°58′29″E / 10.99500°N 104.97472°E |

The ancient Funan sites of Angkor Borei (Khmer: អង្គរបុរី) and Phnom Da (Khmer: ភ្នំដា) are located in the Angkor Borei District, Takéo Province, of southern Cambodia.[1] They are both in the southern part of Cambodia, about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from the western split of Mekong river delta, 150 kilometres (93 mi) from the seacoast, near the Vietnam border and the Óc Eo site.[2][3] The Angkor Borei site was likely an early capital and a region where southeast Asian culture and arts fused in the ancient times.[4] Archaeological excavations have yielded items that are carbon dated to roughly 1523 BC and thereafter, many related to early Buddhism and Hinduism, confirming a continuous human settlement at least for some 500 years.[2] They contain the earliest known dated Khmer inscriptions as well as what may be the earliest tradition of Khmer sculpture.[2]

In recent years, the archeological sites have attracted a growing number of tourists.[5] At the same time, looting and illicit trafficking of antiquities continue as a serious problem in the area.[5] Angkor Borei is particularly challenging area to perform archaeological research on due to the fact that the site is inhabited today.[6] Various areas have been heavily damaged by bulldozing, gardening, and other daily activities.[6]

Angkor Borei

[edit]Like many ancient Asian sites, any initial information came from Chinese documents and accounts.[6] Much archeology has uncovered various previously unknown artifacts and locations. Research has uncovered brick architecture, post holes for a large wooden structure, and a temple containing two Vishnu statues.[6] Brick was not thought to have been used as early as 400 BC.[6] Evidence suggests there may have been a moat or some kind of man made hydraulic system.[6]

Artifacts include ceramics, brick fragments, animal bone, vessels, clay pellets, slag, and stone statues.[6] An analysis of the pottery shows it contains fine orange wares, cord marked earthenware, burnished earthenware, gray wares, and slipped wheel made earthenware.[6]

Based on the style of artifacts and carbon dating, there were three general layers of occupation.[6] The dates also suggest that Óc Eo was also inhabited at the time of Angkor Borei.[6]

Cemetery

[edit]Vat Komnou cemetery is also a notable feature which was excavated and found to contain roughly 60 bodies ranging from 200 BC - AD 400.[7][6] Out of these bodies, 25 were children below 19, 36 were adults, and the remaining were elders.[7] Males were found to be more than twice as common as females, many of which had stress fractures in their lower backs suggesting some sort of heavy labor.[7] An analysis of the bones implies a lack of starvation and extreme stress.[7] The teeth themselves lack common features associated with the consumption of sugars and starches.[7] The cemetery also contained some objects, including beads that are believed to have originated from across southeast Asia like India.[8]

Phnom Da

[edit]The Phnom Da is a granite outcrop and a historic site about 3 kilometers southeast from Angkor Borei. It is notable for the oldest surviving temples, Khmer and Sanskrit inscriptions as a source, as well as perhaps the earliest Cambodian stone statues, based on the epigraphical evidence, iconography, and style, in Cambodia.[3][4]

Statues

[edit]These items are often attributed to the reign of King Rudravarman (514–539 CE).[9] The statues confirm the adoption of ideas from what is now Vietnam and India, along with the Cambodian creativity and innovation with design.[9][3] Among these is the Triad of Phnom Da, a stone statue set of Vishnu and two of his avatars – Rama and Balarama (related to Krishna).[3][10] Vishnu appears as an eight armed figure over 30 meters tall holding attributes in six hands, though it is suspected there were two other attributes that are now lost. Each of the attributes is associated with one of the eight Lokapalas (gods who guard regions of space).[3] While the Triad is made from schist, other free standing stone statues found here – such as the Trivikrama, Krishna Govardhana and Hari Kambujendra – are made of sandstone and also relate to Hinduism and perhaps Buddhism.[3] They display style and iconography similar to the late or post-Gupta Empire period and are said to be remarkably lifelike.[9] Most of these statues have been moved to the Phnom Penh National Museum, in the capital of Cambodia.[3][6][9]

Temple

[edit]The statues appear to predate the stone temple The oldest standing Khmer stone temple (6th-century CE) on the site and may have been preceded by wooden Hindu temples.[3] The inscriptions include 11 Sanskrit lines and 21 Khmer lines which describe the forms of Vishnu and King Rudravarman, along with a ceremony detailing the allocation of land.[3] King Rudravaram included in the temple means that he could have been associated with the religion and seen as an incarnation.[3] He is rumored to have murdered his half-brother for the throne and to strengthen his claim to it, he relied on religion.[3] According to one source however, the dating for the statues could be inaccurate, throwing off the current accepted timeline.[9]

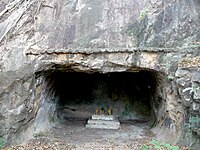

The base of the site is also surrounded by the remains of small caves.[3]

World Heritage Status

[edit]This site was originally added to the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List on September 1, 1992, in the Cultural category.[1] The submission has been renewed on March 27, 2020.[11]

Images

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Site d'Angkor Borei et Phnom Da - UNESCO World Heritage Centre Retrieved on 2009-03-27.

- ^ a b c Peregrine, Peter Neal; Ember, Melvin, eds. (2001). "Angkor Borei". Encyclopedia of Prehistory. Vol. 3 : East Asia and Oceania (2 ed.). Springer Publishing. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-0-306-46257-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Richard M. Cooler (1978), Sculpture, Kingship, and the Triad of Phnom Da, Artibus Asiae, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 29-40, JSTOR 3249812

- ^ a b George Coedes (1968), The Indianized States of Southeast Asia, Susan Brown Cowing (Transl), ed. Walter F. Vella, The University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0824803681, pages 46–62, 67–69, 330–333

- ^ a b Miriam T. Stark and P. Brion Griffin, “Archaeological Research and Cultural Heritage Management in Cambodia's Mekong Delta: The Search for the ‘Cradle of Khmer Civilization,’” in Marketing Heritage: Archaeology and the Consumption of the Past, ed. by Yorke Rowan and Uzi Baram, Walnut Creek, California: Altamira Press, 2004, 117–141.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l STARK, MIRIAM T.; GRIFFIN, P. BION; PHOEURN, CHUCH; LEDGERWOOD, JUDY; DEGA, MICHAEL; MORTLAND, CAROL; DOWLING, NANCY; BAYMAN, JAMES M.; SOVATH, BONG; VAN, TEA; CHAMROEUN, CHHAN; LATINIS, KYLE (1999). "Results of the 1995-1996 Archaeological Field Investigations at Angkor Borei, Cambodia". Asian Perspectives. 38 (1): 7–36. ISSN 0066-8435. JSTOR 42928444.

- ^ a b c d e Pietrusewsky, Michael; Ikehara-Quebral, Rona (2007-03-12). "The Bioarchaeology of the Vat Komnou Cemetery, Angkor Borei, Cambodia". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 26: 86–97. doi:10.7152/bippa.v26i0.11997. ISSN 1835-1794.

- ^ Carter, Alison Kyra; Dussubieux, Laure; Stark, Miriam T.; Gilg, H. Albert (2021). "Angkor Borei and Protohistoric Trade Networks: A View from the Glass and Stone Bead Assemblage". Asian Perspectives. 60 (1): 32–70. doi:10.1353/asi.2020.0036. hdl:10125/108211. ISSN 1535-8283. S2CID 236871871.

- ^ a b c d e DOWLING, NANCY H. (1999). "A New Date for the Phnom Da Images and Its Implications for Early Cambodia". Asian Perspectives. 38 (1): 51–61. ISSN 0066-8435. JSTOR 42928446.

- ^ Bertrand Porte (2006), La statue de Krsna Govardhana du Phnom Da du Musée National de Phnom Penh, UDAYA, Journal of Khmer Studies, APSARA, Vol 7, pp.199-206

- ^ "The Site of Angkor Borei and Phnom Da". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2020. Retrieved 2020-05-28.