Black Death in Sweden

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

The Black Death (Swedish: Digerdöden, 'The Great Death') was present in Sweden between 1350 and 1351.[1] It was a major catastrophe which was said to have killed a third of the population, and Sweden was not to recover fully for three hundred years.

The Black Death in Sweden is only mentioned directly in few contemporary documents; in a letter from the king, in a sermon by Saint Bridget of Sweden, in a letter from the city council in Visby to their colleagues in Lübeck, and in a letter from the Pope, replying to a letter from the Swedish king.[1] There is, however, indirect contemporary information, as well as later descriptions of it.

Background

[edit]Sweden in the mid-14th century

[edit]At this point in time, Sweden was in a personal union with Norway under the same king, Magnus Eriksson. In 1348, the king had conducted a crusade against the Orthodox Russians in the border of Finland, and conducted another in 1350, the year of the plague.[1] Sweden was a nation progressing in many ways: the first national law constitutions, the Magnus Erikssons landslag and the Stadslagen, was introduced during this period.

The Black Death

[edit]Since the outbreak of the Black Death in the Crimea, it had reached Sicily by an Italian ship from the Crimea. After having spread across the Italian states, and from Italy to France from France to England, the plague reached Norway by a plague ship from England in the summer of 1349. In the summer of 1350, Sweden was surrounded by plague in Norway to the West and Denmark to the South.[2]

Plague migration

[edit]

The bubonic plague pandemic known as the Black Death reached Western Sweden from Norway in the late summer or autumn of 1350, and appears to have reached Central Sweden from Gotland during the spring and summer of the same year.[2]

The progress of the Black Death in Sweden is not directly described in contemporary sources, but it can be traced by indirect documentation such as wills and donations to the church, and by tracing the residence of the king, who continually moved away from the plague to places where it had not yet arrived, or from where it had already passed.[2]

In 1349, King Magnus of Sweden and Norway issued a warning about the plague to his Swedish subjects. While the letter is not dated, it was likely written in Lödöse in September 1349, judging from the known place of residence and other letters issued by the king which has been dated.[2] In the letter, it is clear that the plague had not reached Sweden and that the king issued a royal proclamation of public penance, in an attempt to soften the wrath of God to prevent the Black Death in Norway from reaching Sweden:

- "We proclaim to You, that we have been given tidings that are truly frightening, and of which every Christian should justly fear; that God has because of the Sins of Man cast a great misery upon the entire world, that of hasty evil death, so that most of the people who lived in the lands West of our land are now dead of that misery and it is now present in all of Norway and Halland and are progressing toward us, so that everywhere in those lands it is so strong that people [with no prior illness] falls down and dies, when a moment ago they were healthy [...]; and where ever it progresses not enough people are left who can bury those that die. Now We fear, because of the great love and care we have for you that, because of the Sins of Man, the same misery and death should come over our own subjects."[1]

In order to prevent the plague from reaching Sweden, the king issued several commands. In Europe, the plague was commonly believed to be a punishment from God for the Sins of humanity. Therefore, the commands of the king was of religious nature and designed to lessen the wrath of God. In the public royal letter, which was circulated to the Bishops of the Kingdom, all Swedes regardless of class, age or gender were commanded to regularly attend mass, give alms to the poor, confess and do penance, fast on water and bread every Friday and give what they could to the Virgin Mary, the church and the king.[1]

The Black Death first appeared in Sweden in the big port city of Visby on Gotland, likely by ship from Denmark or Germany, where it was present in May or at the latest July 1350.[2] In July 1350, nine people were burned in Visby after having confessed under torture that they had caused the plague by poisoning. Two of them were priests who confessed that they had poisoned the mass cloth (which the parishioners kissed during mass) with plague during Whit Monday mass in May, and the other seven were men employed by the church who confessed to having poisoned wells and lakes in Stockholm, Västerås and Arboga and across the Swedish countryside.[2] This case was described in a letter from July 1350 to the city council of Rostock in Germany received a letter from the city council of Visby in Sweden.[1]

In June 1350, the king was in Bergen in Norway, where the plague had died out by that time: he continued to Stockholm in August, but immediately left for Åland when the plague reached Stockholm the same month, and continued from Åland to Reval, where he stayed from December 1350 to May 1351, when he finally returned to Stockholm after the Black Death had begun to subside in Sweden.[2]

The Black Death appears to have first reached Gotland by sea in the spring or early summer of 1350, and spread across Eastern and Central Sweden during the summer and autumn: from Småland and Östergötland to Närke and Uppland between August and December 1350, with a presence in Stockholm and Uppsala in August.[2] The progress of the plague in Western and Northern Sweden is not as clearly visible. In September 1350, the plague was present in eastern Norway along the Western border of Sweden, in Norwegian Jämtland North of Sweden, and in Danish Skåne south of the Swedish border,[2] making it likely to have reached Western Sweden from Norway slightly later, in the autumn of 1350. Northern Sweden is completely unknown it this respect, but it is noted that the colonization of the Torne Valley stopped suddenly in the 14th century and did not resume for two centuries.[1]

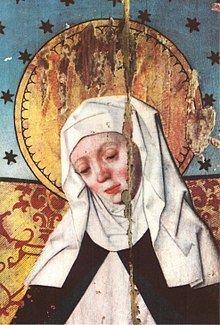

Saint Bridget of Sweden commented on the Black Death in Sweden:

- "For three Sins did the misery come to the realm, that is for pride, intemperance and greed. Therefore God can be placated by three things, so that the torment may be shortened."[1]

She stated that the Black Death had reached Sweden because of the Sins of pride, intemperance and greed, particularly because of the sinful dress fashion of the women, and that the wrath of God could be placated if the Swedes abstained from sinfully provocative fashion; if the parish priests lead their congregations in penance; and if the bishops organized public penitence masses in the cathedrals and washed the feet of the poor.[1]

Sometime in the summer or autumn in 1350, King Magnus sent a letter to Pope Clemens VI in Avignon. In March 1351, the pope sent a letter to Sweden in Norway as a reply to this letter, in which he ordered the Bishops of Lund, Uppsala and Trondheim to encourage their parishioners to join the king in his crusade against the Orthodox Russians, because so many of his soldiers and subjects had died during the plague that he was forced to interrupt his crusade.[1]

Finland

[edit]Finland was at this point a part of Sweden and it has sometimes been assumed that the plague was present there in 1351–1352. It is unconfirmed whether the Black Death ever reached Finland, as there are no direct references to its presence there. In 1352, the priests of Turku parish were forbidden to leave their parishes, which may be interpreted as a way to ban them from abandoning their parishioners during the plague, but the reason for this prohibition is not stated.[2] It is noted that Finland also had its "plague legends" about the Black Death, which are similar to those in Sweden, but it is unknown if these legends in fact originates from the Black Death of the 1350s or later plagues.

It has been suggested that the plague never reached Finland because the contacts between Sweden and Finland was disconnected during the Black Death [3] or that it did reach Finland but had less impact, because the low population made it difficult for it to spread.[1] The Black Death did reach neighboring Russia, where it is known to have been present in 1352-1353 before tempering out; but it likely reached Russia by way of the Baltics, where the Black Death was present in 1351–1352 and to where it had migrated from Germany.[1]

Victims

[edit]Death toll

[edit]No individual is positively identified as a victim of the Black Death in Sweden in 1350–1351. It is commonly assumed that the king's two stepbrothers, the sons of his mother Ingeborg of Norway and stepfather duke Canute Porse the Elder, died from the Black Death, as were many individuals who were noted to have died in 1350 or 1351, but in no case are there any contemporary documents which can verify it.[2]

While the deaths from the Black Death in Sweden is unknown, it was mentioned as a cause to why Sweden had such a low population for centuries, and it is clear that the plague caused a demographic shock, and that the population did not recover until the 17th century.[1]

Social distribution

[edit]Prior to the 15th century, very few people in Sweden below the social elite are documented in any large degree. Only the nobility and the priesthood class are sufficiently recorded to make estimations somewhat possible.[2]

It is noted that a disproportional number of the nobility died during the 1350-1351 plague years, particularly among the lower nobility, but less so among the higher levels: twelve of the fifteen members of the Royal Council survived, and of the remaining three who did die during the plague years, two were elderly and may have died of natural causes.[2] The priesthood was the most well documented class from this period in Sweden, and it appears half of the parish priests in Västerås and Strängnäs may have died judging from the fact that about half of them were replaced in the years after the Black Death, but only a quarter of the canons; it is also a fact, that all of the Bishops in Sweden (with Finland) survived the Black Death.[2] This appears to show that the elite survived better than the lower social levels, as the lower clergy and lower nobility were more severely affected than the higher levels of the same classes.[2]

The fact that the Swedish elite appear to have survived the Black Death is a contrast to neighboring Norway, where more of the elite classes appear to have died of the Black Death, which made Norway more vulnerable and destabilized following the Black Death and may have contributed to the different positions of Norway and Sweden during the Kalmar Union later that century, during which Sweden managed to keep more of its political independence than Norway.[1]

Consequences

[edit]

Economic, social and political effects

[edit]The population loss caused a crisis during which the nobility unsuccessfully attempted to introduce serfdom in the 15th century.[2] This was similar to Denmark, with the exception that in neighboring Denmark the nobility did succeed in introducing serfdom (Vornedskab). The Swedish nobility was however not to be so successful.

The great loss of lives contributed to higher demands from the surviving workers upon the elite, who responded with refusals and attempts at greater repression, which resulted in great social tensions. This was common for many countries after the Black Death. These events are not as documented in Sweden as elsewhere. A donation of a property from Lady Margareta, the widow of Avid of Risnäs, and her son Stefan to the Linköping Cathedral on 13 June 1353, is a rare example of this, as the document clearly states that they had to sell the property for a much lower price than its actual worth:

- "...because of the great mortality recently, and the devastation of so many properties, which could hardly be sold for half of its worth because of the rarity of people who can work them."[1]

The higher demands of the workers and peasants and the lower incomes of the nobility caused social tensions that resulted in several local charters such as the Skara Charter of 1414 and the Växjö Charter of 1414, which attempted to introduce serfdom by forcing the tenant farmers to stay on the noble estates with heavy regulations, restricting their rights to move and raising their obligation to work on the noble estates and their taxes to the landlords; in Sweden, however, the power of the nobility and the feudal system was too weak for any serfdom to be successfully introduced, and these laws do not appear to have been effective.[1] During the 15th century, however, several peasant rebellions took place in Sweden and the century is described as one of crisis and social tensions.[1]

In the Engelbrektskrönikan ('Engelbrekt Chronicle') from the 1430s, there were complaints about the heavy taxes imposed by Eric of Pomerania with reference to the Black Death, as the king was criticized for demanding a tax which the country could no longer afford, as the population had decreased by the 'Great Death' since then, which devastated the land so that "where former one hundred farmers were, there are now but twenty".[1]

Religious and cultural consequences

[edit]The Black Death was long remembered in Sweden as a catastrophe and referred to why Sweden had such a small population. For centuries, ruins in the forests were often explained as remains from towns and villages devastated by the "Great Death".[1]

Vadstena Abbey was not yet founded in 1350, but the Bridgettine monk Anders Lydekesson (d. 1410) nevertheless included a description of it in his chronicle from 1403 to 1408, in which he mentioned for the year of 1350:

- "At that time a great mortality ravaged the Kingdom of Sweden; no one can recall that there has ever been such an epidemic before nor after."[1]

Bishop Peder Månsson of Västerås noted that many farms belonging to the Bishopric were still deserted because of the Black Death, and Olaus Petri attributed the small population of Sweden to the Black Death and referred to it as the cause to why there were wilderness and forests where there had previously been villages and farms.[1]

There are several local legends of the devastating effects of the plague. A common theme of them was, that in one parish, only one man survived, and in the neighboring parish, only one woman survived; that they found each other after having sounded the church bells, and that they married and became the ancestors of a new village.[1]

Recurrences

[edit]The Black Death would return regularly, but with fewer death victims, until the 18th century. Sweden was reached also by the second and third European Black Death epidemic of 1359–1360 and 1368–1370. King Magnus Eriksson's son and co-regent Erik Magnusson, his consort Beatrix, and their children possibly died of the plague in 1359.[4] The plague also returned in repeated national epidemics in 1413, 1421–22, 1439–40, 1451, 1455, 1464–65, 1472–74 and 1495. Of these, the plagues of 1413, 1420–22 and 1464-66 are described as particularly severe.[2]

After the Middle Ages, the plague returned in 1548–49, 1565–66, 1572, 1576, 1580, 1603, 1623, 1629–30, 1638, 1653 and 1657, before the Great Northern War plague outbreak in 1710–1713, which was to be the last outbreak of Bubonic plague in Sweden.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Harrison, Dick, Stora döden: den värsta katastrof som drabbat Europa, Ordfront, Stockholm, 2000 ISBN 91-7324-752-9

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Janken Myrdal: Digerdöden, pestvågor och ödeläggelse. Ett perspektiv på senmedeltidens Sverige

- ^ Ole Jørgen Benedictow: The Black Death, 1346-1353: The Complete History

- ^ Beatrix, urn:sbl:19091, Svenskt biografiskt lexikon (art av S. Tunberg), hämtad 2020-07-07.

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Swedish. (May 2020) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|