Calvin Hoffman

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Calvin Hoffman (1906 – February 1986),[1] born Leo Hochman in Brooklyn, New York, was an American theater critic, press agent and writer who popularized in his 1955 book The Man Who Was Shakespeare[2] the Marlovian theory that playwright Christopher Marlowe was the actual author of the works attributed to William Shakespeare. Like other alternate Shakespearean authorship theories, Hoffman's claims have been largely dismissed by mainstream Shakespearean scholars.

Hoffman's theory

[edit]Hoffman was not the first to argue that someone other than William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote the plays attributed to him, nor was he even the first to suggest Marlowe as the main candidate. In fact three people—Wilbur G. Zeigler in 1895,[3] Henry Watterson in 1916,[4] and Archie Webster in 1923,[5] had beaten him to it, but he denied having known about any earlier proponent for the first twelve years of his research into the subject,[6] and he certainly achieved far more than any of them to bring it to the attention of a wider public.

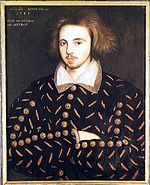

The "Marlowe" portrait

[edit]

In 1953 an Elizabethan painting in a very poor condition was found at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where Marlowe had studied, and it was Calvin Hoffman who first suggested that it was in fact a portrait of Marlowe himself.[7] The details of the sitter's age in 1585 matched Marlowe's exactly, and the motto Quod me nutrit me destruit (that which nourishes me destroys me) seemed particularly apt. Although other images had been used or created for Marlowe before that, and the College still prefers it to be referred to as a "putative" or "apocryphal" portrait of him, this is the one which most people would nowadays associate with Marlowe.[8]

Walsingham's tomb

[edit]The UK publication of his book coincided with an attempt by Hoffman to obtain a faculty (a license) to open the tomb, at Chislehurst in Kent, of Thomas Walsingham, Marlowe's patron—and, according to Hoffman, his lover—to see whether the copies of any Shakespeare plays had been buried with him. He was allowed to open only the chest tomb surmounting the family vault, however, and found nothing but sand. Much later, however, in 1984, he was allowed to drill through the floor of the church to peer into the tomb itself, but all that could be seen was a jumble of lead coffins, and nothing which looked like a box of papers.[9]

The Marlowe Society

[edit]During the visit to Chislehurst in 1955, Hoffman took part in a debate on his version of the Marlovian theory with the headmaster of the local school at Chislehurst library. Although Hoffman lost the debate, the sell-out event brought together many people with an interest in Christopher Marlowe, as a result of which the UK's Marlowe Society—although concerned more with Marlowe as a poet/dramatist in his own right than with the authorship theory—came into existence just a week or two later.

Marlowe and Padua

[edit]In 1983, Hoffman was left some notes by a journalist friend of his concerning someone called Pietro Basconi who in 1627 had apparently nursed Christopher Marlowe when he was terminally ill in Padua, Italy.[10] Determined to follow this up he went to Padua in 1985, accompanied by an Italian-speaking couple, Dr. Frank Haines and his wife Jean, but nothing was found to support the story. It was not until some three years later that Hoffman seems to have discovered that it originated in the editorial by Henry Watterson cited above, but it still isn't clear whether he understood that Watterson had invented this part of the story only jokingly, to illustrate how it might be proved.

The Hoffman Prize

[edit]Anxious that the Marlovian theory should not die with him, Hoffman arranged in 1984 a deal with Marlowe's school, The King's School, Canterbury, that in exchange for his leaving a large sum of money to them in his will they would administer an annual essay competition related to "the life and works of Christopher Marlowe and the authorship of the plays and poems now commonly attributed to William Shakespeare with particular regard to the possibility that Christopher Marlowe wrote some or all of those poems and plays or made some inspirational creative or compositional contributions towards the authorship of them."

It was also agreed that "[i]f in any year the person adjudged to have won the Prize has in the opinion of The King's School furnished irrefutable and incontrovertible proof and evidence required to satisfy the world of Shakespearian scholarship that all the plays and poems now commonly attributed to William Shakespeare were in fact written by Christopher Marlowe then the amount of the Prize for that year shall be increased by assigning to the winner absolutely one half of the capital or corpus of the entire Trust Fund".

Nobody has come anywhere near achieving the latter, and Hoffman's intentions for the essay have been reinterpreted nowadays as a prize for "a distinguished publication on Christopher Marlowe". Since 1988, when the first Calvin & Rose G. Hoffman Memorial Prize was awarded, only four of the thirty prize-winning essays have actually espoused his theory. On the other hand, the prize has undoubtedly stimulated research into the life and works of Christopher Marlowe, and books have even been published which might not have been written to begin with without the stimulus of the Calvin & Rose Hoffman prize.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ Los Angeles Times, 1 March 1986.

- ^ Hoffman 1955 It was published again later as The Murder of the Man Who Was "Shakespeare", Hoffman 1960.

- ^ Zeigler 1895

- ^ Watterson 1916

- ^ Webster 1923

- ^ Hoffman 1955, pp. 14–15

- ^ Hoffman 1955, pp. 65–67

- ^ Nicholl 2002, pp. 7–9

- ^ Part of the BBC film recording this event can be seen in Michael Rubbo's Much Ado About Something, a film about the Marlovian theory produced in 2001.

- ^ This was reported in the newspaper The Guardian on 11 July 1983

- ^ For example, Bate 1998 and Riggs 2004 both contain chapters based upon the authors' prize-winning essays.

Further reading

[edit]- Bate, Jonathan (1998). The Genius of Shakespeare. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512823-9. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- Hoffman, Calvin (1955). The Man Who Was Shakespeare. London: Max Parrish.

- Hoffman, Calvin (1960). The Murder of the Man Who Was "Shakespeare". New York: Julian Messner.

- Nicholl, Charles (2002). The Reckoning: The Murder of Christopher Marlowe (2nd ed.). London: Vintage. ISBN 0-09-943747-3.

- Riggs, David (2004). The World of Christopher Marlowe. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-22160-2.

- Watterson, Henry (1916). "The Shakespeare Mystery". The Pittsburgh Gazette Times. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- Webster, Archie (1923). "Was Marlowe the Man?". The National Review. 82: 81–86. Archived from the original on 2 October 2010. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- Zeigler, Wilbur Gleason (1895). It was Marlowe: a Story of the Secret of Three Centuries. Chicago: Donohue, Henneberry & Co. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

External links

[edit]- The International Marlowe-Shakespeare Society. ("Our Belief is that Christopher Marlowe - in his day England's greatest playwright - did not die in 1593 but survived to write most of what is now assumed to be the work of William Shakespeare.")

- The Marlowe-Shakespeare Connection: (a Marlovian website/blog started in May 2008, with regular contributions from leading Marlovians.)

- The Marlowe Society. (Although the Society is mainly concerned with Christopher Marlowe as a poet/dramatist in his own right, they are happy to allow discussion of the Marlovian authorship theory.