Charles Bingham Penrose

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Charles Bingham Penrose | |

|---|---|

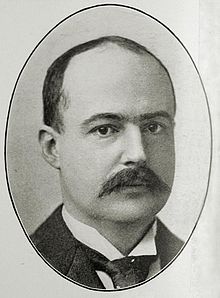

Penrose in 1902 | |

| Born | February 1, 1862 |

| Died | February 28, 1925 (aged 63) Near Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Pennsylvania |

| Known for | Penrose drain |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Gynecology |

Charles Bingham Penrose (February 1, 1862 – February 28, 1925) was an American gynecologist, surgeon, zoologist and conservationist, known for inventing a type of surgical drainage tubing called the Penrose drain. He was a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote several editions of a textbook on medical problems in women, and was named a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

A native of Philadelphia, Penrose was the son of a medical school professor, and his brothers included U.S. senator Boies Penrose, mining engineer R. A. F. "Dick" Penrose and geologist Spencer Penrose. The grandson of prominent politician Charles B. Penrose, he married into the wealthy Drexel family of the same city. Penrose held two doctorates, which he earned concurrently: a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania and a Ph.D. in physics from Harvard College.

After completing residency training at Pennsylvania Hospital, Penrose founded Philadelphia's first hospital for women and became a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. He was interested in the idea of facilitating surgical site drainage in abdominal surgery patients, but he was concerned about the risks of the drains available in the late 19th century. This led him to create the Penrose drain, a soft tube that he fashioned out of a condom with its tip removed.

After he contracted tuberculosis in 1891, Penrose left Pennsylvania for Wyoming, hoping that the change in climate would restore his health. While he was in Wyoming, Penrose became involved in the range conflict known as the Johnson County War; he was arrested after the deaths of two alleged cattle rustlers, and only his friendship with the governor of Wyoming prevented him from being lynched. Returning to Philadelphia after the conflict, Penrose wrote a memoir (The Rustler Business) about his time in Wyoming. For the last two decades of his life, Penrose directed much of his attention to zoology and conservation issues. He established a zoological laboratory at the Philadelphia Zoo, the first such laboratory at a U.S. zoo.

Early life and family

[edit]Penrose was born in Philadelphia on February 1, 1862.[1] He was a descendant of Bartholomew Penrose, who had settled in the city in 1698, establishing a shipyard at the invitation of William Penn that stayed in the Penrose family for 150 years.[2] Charles Penrose's father, Richard Allen Fullerton (R. A. F.) Penrose Sr., was a physician, an obstetrics professor at the University of Pennsylvania, and one of the founders of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.[3][4] Charles's mother, Sarah Hannah Boies Penrose, had come from Maryland and was the adopted granddaughter of Jeremiah Smith Boies, an affluent Boston merchant. Soon after her marriage to R. A. F. Penrose, Sarah turned away from high society and focused on providing education for her seven sons.[5]

Despite the family's wealth, Charles Penrose and his siblings grew up in a modest townhome at 1331 Spruce Street in Philadelphia. The family's proximity to the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers allowed the Penrose brothers to enjoy fishing, ice skating, and swimming. The Penroses attended the Centennial Exposition in 1876.[6] In his early years, Penrose was taught largely by private tutors.[3] Later, he and his brother Boies attended Episcopal Academy in Newtown Square, Pennsylvania, where they excelled academically with grade-point averages that fell within 0.1 percentage points of each other. Penrose was 15 months younger than Boies, but they went off to Harvard College at the same time, living together in Boston in a house owned by an aunt.[7]

In addition to his father, Penrose had several well-known relatives. His grandfather, Charles B. Penrose, was a Pennsylvania state senator who first introduced the "unit rule" at political party conventions to ensure that the Whig Party nominated William Henry Harrison for president over Henry Clay in 1839.[4][8] His six brothers included Boies Penrose, a Pennsylvania state legislator and U.S. senator who ran the powerful Republican political machine in Pennsylvania for 17 years; R. A. F. "Dick" Penrose, a mining engineer and president of the Geological Society of America; and Spencer Penrose, a geologist, philanthropist and builder of the Colorado hotel known as The Broadmoor.[4][9][10]

Education

[edit]Penrose completed a physics degree at Harvard with highest honors in 1881, graduating at age 19, two months after his mother died of tuberculosis.[3] He wanted to pursue a medical degree at the University of Pennsylvania concurrently with a Ph.D. in physics at Harvard. The schools worked out an arrangement that involved Penrose's traveling to Harvard for two months out of each year. At Harvard, Penrose studied under physicist John Trowbridge, who was known for his work in electricity and magnetism. In volume 17 of the Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1881–82), Penrose published two papers: "Thermo-electricity – Peltier and Thomson effects" and "Thermo-electric line of copper and nickel below 0°".[11] His physics PhD thesis was titled "The mathematical theory of thermoelectricity and the relation between thermoelectricity and superficial energy".[12] Penrose graduated from both programs in 1884 at age 22.[3] He finished medical school one year behind Amos W. Barber; the two became friends there, and Barber later became the acting governor of Wyoming.[13]

After completing the doctorates, Penrose turned his attention away from physics and toward the practice of medicine.[11] Penrose was a resident at Pennsylvania Hospital in 1885 and 1886.[14] While he was a resident, Penrose participated in research with Jacob Mendes Da Costa on the diuretic effects of injected cocaine. The resulting article, "Observations on the diuretic influence of cocaine", was published in a local medical journal called The College and Clinical Record.[15]

Career

[edit]Penrose remained in Philadelphia after his residency, having been hired as an attending outpatient surgeon at Pennsylvania Hospital.[14] After contracting tuberculosis in 1891, Penrose left his Philadelphia medical practice. On the advice of Amos Barber, who was by then the acting governor of Wyoming, Penrose came to that state, and Barber had him put up at the Cheyenne Club, one of the wealthiest and most exclusive establishments on the frontier. Penrose placed himself on a regimen of physical activity; he dug with a pick and shovel in the morning and rode horses in the afternoon. By early the next year, he had gained 20 pounds (9.1 kg)[13]

Returning to Philadelphia, Penrose was hired as Professor of Gynecology for the medical school at the University of Pennsylvania in 1893, succeeding William Goodell.[14] He authored the Text-Book on Diseases of Women (1897), which the Cincinnati Lancet-Clinic described as a concise text that was well-suited for medical students and general practitioners.[16][17] By 1908, six editions of the book had been published, though a review in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal said that "in every essential respect [the sixth edition] is the fifth edition over again."[18]

Along with Herbert Fox and Ellen Corson-White, Penrose established the study of zoo-based pathology in North America.[19] He founded the Penrose Research Laboratory at the Philadelphia Zoo in 1901, the first zoological laboratory located inside an American zoo. The lab conducted important research into the prevention of tuberculosis and studied the impact of diet on animal fertility and on the richness of animal coats.[20] While working at the Penrose Research Laboratory, Corson-White developed "Zoo Cake", which became a popular nutritional product for zoo animals.[21] In the foreword to Fox's Disease in Captive Wild Mammals and Birds (1923), he decried the fact that most animal diseases were poorly understood, especially relative to the progress that had been made in human medicine.[19] Fox's book is dedicated to Penrose.[22]

Penrose was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1909.[23] In 1911, Penrose was named a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science; he belonged to several sections of the organization.[24] He served as the president of the Zoological Society of Philadelphia from 1909 until his death. A well-respected conservationist, he also spent many years as president of the Pennsylvania Fish and Game Commission.[25]

Contributions as a surgeon

[edit]Penrose drain

[edit]In the late 19th century, surgeons were divided on whether drainage tubes should be used frequently or infrequently in abdominal surgery. Penrose was an advocate of the maxim "When in doubt, drain."[26] He made a presentation on the topic before the American Medical Association in 1889.[27] Most surgical drains at the time were made of gauze or of glass tubes.[26] Such drains could adhere to the surrounding tissue of the abdomen, so there was a risk of injury to bowel or other tissues upon drain removal.[26] In 1890, Penrose designed a rubber drain made of a condom with its tip cut off. The Penrose drain became the dominant surgical drain until suction drainage was introduced in the 1950s.[28]

Gynecean Hospital

[edit]Penrose and his father participated in the founding of the Gynecean Hospital, which opened in January 1888 as the first hospital in Philadelphia that was exclusively for women. Penrose served as the hospital's chief surgeon, and his father was its president. The hospital was run out of a small home on Cherry Street until it moved to a home near the intersection of Hamilton Street and 18th Street on April 1. The hospital was permanently established at 247 N. 18th Street in 1891. Penrose and Joseph Price served as attending surgeons until late 1890, when Price resigned and was replaced by David Hayes Agnew.[29]

In 1901, the hospital attracted criticism from The Times, a Philadelphia newspaper, in an article that examined $3 million in state funds that had been awarded to Philadelphia hospitals over a 30-year period. The hospital was criticized because it had received $175,000 since 1889, because it was impossible to tell whether the hospital ever treated poor patients, and because Penrose's brother was a senator.[30]

Penrose remained associated with the Gynecean Hospital for life. By 1924, as chairman of the hospital's board of directors, Penrose recommended that the facility be abandoned because it was only filled to ten percent of its capacity.[31] The following year, Gynecean Hospital merged with the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.[32]

Johnson County War

[edit]While he was at the Cheyenne Club recovering from tuberculosis, Penrose agreed to serve as the surgeon on an invasion led by a group of cattlemen, the Wyoming Stock Growers Association (WSGA). The men were responding to the perceived threats posed by settlers with smaller cattle operations. The conflict became known as the Johnson County War.[13] Penrose was friends with the novelist Owen Wister, whose most well-known work was The Virginian, a fictionalized version of the events of the Johnson County War.[33] Penrose wrote a letter to Wister during the conflict, and in doing so, he may have inspired the most well-known line in The Virginian ("You son-of-a--"). He had written in his letter that "during the last two months 'son of a bitch' has been a favorite expression in this country. Wyoming is in the son of a bitch stage of her civilization and could not get on any more without it than she could without a lariat and a branding iron."[34]

When two alleged cattle rustlers, Nate Champion and Nick Ray, were ambushed and killed by a group of the cattlemen, Penrose was among the suspects arrested. He was taken to Douglas, Wyoming, where lynching was briefly considered. Governor Barber, who had also been a longtime friend of the cattlemen, intervened; he had Penrose brought back to the Cheyenne Club by a U.S. marshal on a writ of habeas corpus. Penrose was ultimately cleared of responsibility in the attack.[33]

In 1914, Penrose wrote a memoir, The Rustler Business, about the events in Wyoming. Author John W. Davis wrote that Penrose's account is especially valuable because Penrose was not entirely familiar with the official opinions held by the group of cattlemen. Penrose parroted some of the myths that were widely held by the group, such as the thought that Cattle Kate needed to be killed in the interests of the country. However, Penrose also expressed ideas that differed from those held by the men of the WSGA, such as the admission that the cattleman invaders had started north with the goal of targeting 70 specific people, including Nate Champion.[13]

Personal life

[edit]Penrose, who stood six feet (183 cm) tall with an athletic build, was very physically active as a young man, having once traveled on horseback from Philadelphia to Niagara Falls and back. On another occasion, after Penrose and a friend had discussed the subject of endurance, he swam 15 miles (24 km) in the ocean in five hours, his friend having dared him to attempt the swim.[3]

On a hunting trip in Montana, Penrose killed a bear cub and was nearly mauled to death by the cub's mother, escaping only after he shot the bear in the throat.[27] He was left with bones protruding from his wrist, and he performed surgery on himself that kept his hand intact.[3] Despite also seeking care for his hand at the Mayo Clinic, Penrose never performed surgery after the 1897 incident with the bear.[35]

Though he was one of seven brothers, Penrose was the only one of them to have children.[36] He married Katharine Drexel, the daughter of philanthropist Joseph William Drexel, in New York City in 1892.[37] The couple had a daughter named Sarah in 1896, and they had a son named Charles who was born in 1900 and died the next year. Their third child, Boies Penrose, became an author and travel historian.[38] Katharine Drexel was known in Philadelphia as a member of the anti-suffragism movement. She died in 1918.[39]

Death

[edit]For the last several years of Penrose's life, he was in poor health.[40] He spent the winter of 1924–25 attempting to recover from tuberculosis in Aiken, South Carolina.[41] Penrose made what was supposed to be a brief trip back to Philadelphia to visit relatives, and he was accompanied by two nurses and a cousin named Sarah. He was found dead of a suspected heart attack in his drawing room on the train near Washington, D.C., on February 28, 1925.[42] He was interred at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.[43]

He left most of his million-dollar estate to his two children, and he left $100,000 to Mary Devinnie, a nurse who had cared for him late in his life.[44]

Mount Penrose in the Flathead Range in Montana is named in his honor.[45]

Selected publications

[edit]- Penrose, Charles Bingham (1881). "Thermo-electricity. Peltier and Thomson effects". Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 17: 39–46. doi:10.2307/25138640. ISSN 0199-9818. JSTOR 25138640.

- Penrose, Charles Bingham (1881). "Thermoelectric line of copper and nickel below 0°". Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 17: 47–54. doi:10.2307/25138641. ISSN 0199-9818. JSTOR 25138641.

References

[edit]Citations

- ^ Leach 1903, p. 107.

- ^ Noel & Norman 2002, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f Powell, John L. (2002). "Charles Bingham Penrose, MD (1862–1925)". Journal of Pelvic Surgery. 8 (3): 129–130.

- ^ a b c Beers, Paul B. (2010). Pennsylvania Politics Today and Yesterday: The Tolerable Accommodation. Penn State Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0271044989.

- ^ Leach 1903, p. 106.

- ^ Noel & Norman 2002, pp. 2–5.

- ^ Lukacs 1980, p. 41.

- ^ Potts, C. S. (1912). "The unit rule and the two-thirds rule". American Review of Reviews. p. 706.

- ^ "GSA Today – 1930 Presidential Address: Geology As An Agent In Human Welfare". www.geosociety.org. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ Dallas, Sandra (July 3, 2008). "Broadmoor builder's rollicking, frolicking life – The Denver Post". The Denver Post. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Hall, Edwin. "Biographical Memoir of John Trowbridge 1843–1923" (PDF). National Academy of Sciences. p. 191.

- ^ "Harvard Physics PhD Theses, 1873–1953" (PDF). Harvard University. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Davis, John W. (2012). Wyoming Range War: The Infamous Invasion of Johnson County. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 132–135. ISBN 9780806183800.

- ^ a b c Leach 1903, p. 122.

- ^ Da Costa, J. M.; Penrose, C. B. (1886). "Observations on the diuretic influence of cocaine". The College and Clinical Record. 7 (7): 131.

- ^ "A Text-book of Diseases of Women". Cincinnati Lancet-Clinic. 39 (13): 315. 1897.

- ^ "Book reviews". Cincinnati Lancet-Clinic. 47: 497. 1901.

- ^ "Book review: A Textbook, of Diseases of Women". Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. 159 (26): 875. December 24, 1908. doi:10.1056/NEJM190812241592620.

- ^ a b Bell, Catharine E. (2001). Encyclopedia of the World's Zoos. Taylor & Francis. p. 1291. ISBN 9781579581749.

- ^ Philadelphia, a Guide to the Nation's Birthplace. Pennsylvania Historical Commission. 1937. p. 562. ISBN 9781623760588.

- ^ Hingston, Sandy (December 19, 2020). "The Day the Great Apes Died: The Legacy of the 1995 Philadelphia Zoo Fire".

- ^ Fox, Herbert (1923). Disease in captive wild mammals and birds: Incidence, description, comparison. J. B. Lippincott & Co.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved December 14, 2023.

- ^ Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 1912. p. 279.

- ^ Brown, C. Emerson (1925). "Charles Bingham Penrose". Journal of Mammalogy. 6 (3): 203–205. ISSN 0022-2372. JSTOR 1373635.

- ^ a b c Baskett, Thomas F. (2019). Eponyms and Names in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Cambridge University Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-1-108-38619-7.

- ^ a b Romm, Sharon (1982). "The Person Behind the Name: Charles Bingham Penrose". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 70 (3): 397–399. doi:10.1097/00006534-198209000-00023. PMID 7051062.

- ^ Giakoumis, Matrona. "Update 2012: 51. Use of drains in foot and ankle surgery" (PDF). The Podiatry Institute. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- ^ Penrose, Charles B. (1909). "The Gynecean Hospital". In Henry, Frederick P. (ed.). Founders' Week Memorial Volume. F. A. Davis Company. pp. 831–834.

- ^ "Hospitals that get state money". The Times. July 7, 1901.

- ^ "Gynecean Hospital inquiry demanded". The Philadelphia Inquirer. June 16, 1924.

- ^ "Philadelphia Medical History and the University of Pennsylvania". University Archives and Records Center. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ^ a b Thrapp, Dan L. (1991). Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography: P-Z. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 1130–1131. ISBN 0803294204.

- ^ Bold, Christine (2013). The Frontier Club: Popular Westerns and Cultural Power, 1880–1924. Oxford University Press. pp. 76–78. ISBN 9780199731794.

- ^ Noel & Norman 2002, p. 12.

- ^ Lukacs 1980, p. 61.

- ^ "Yesterday's weddings: Penrose-Drexel". The New York Times. November 18, 1892.

- ^ "Boies Penrose, 73, travel historian". The New York Times. March 1, 1976.

- ^ "Penrose voted against suffrage as aunt urged". Evening Public Ledger. February 11, 1919.

- ^ "Dr. C.B. Penrose dies suddenly". The Wilkes-Barre Record. February 28, 1925.

- ^ "Dr. Charles B. Penrose dies". Aiken Standard. March 6, 1925.

- ^ "Boies Penrose's brother is dead". Scranton Republican. February 28, 1925.

- ^ "Charles B Penrose". remembermyjourney.com. webCemeteries. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

- ^ "Will of Penrose leaves $100,000 to trusted nurse". New Castle News. March 5, 1925.

- ^ "Flathead National Forest Hikes". www.mossmountaininn.com. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

Sources

- Leach, Josiah Granville (1903). History of the Penrose Family of Philadelphia. Wm. F. Fell Company.

- Lukacs, John (1980). Philadelphia: Patricians and Philistines, 1900-1950. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-5597-6.

- Noel, Thomas; Norman, Cathleen (2002). A Pike's Peak Partnership: The Penroses and the Tutts (PDF). University Press of Colorado.