Dom Mintoff

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Dominic Mintoff KUOM (Maltese: Duminku Mintoff, [dʊmˈɪnku mˈɪntɒff]; often called il-Perit, "the Architect"; 6 August 1916 – 20 August 2012)[1] was a Maltese socialist politician, architect, and civil engineer who was leader of the Labour Party from 1949 to 1984, and was 8th Prime Minister of Malta from 1955 to 1958, when Malta was still a British colony, and again, following independence, from 1971 to 1984.[2] His tenure as Prime Minister saw the creation of a comprehensive welfare state, nationalisation of large corporations, a substantial increase in the general standard of living and the establishment of the Maltese republic,[3][4][5] but was later on marred by a stagnant economy, a rise in authoritarianism and outbreaks of political violence.[6][7][8][9]

Early life and education

[edit]Mintoff was born on 6 August 1916, the third-born and eldest male sibling of nine, born to Lawrence (or Laurence) "Wenzu" Mintoff (who hailed from an old Gozitan family) and his wife, Concetta Farrugia (known in Maltese as Ċetta tax-Xiħ).[10] He was baptised the next day in his hometown Bormla in the Sanctuary of the Immaculate Conception.[11] His father was a local cook employed by the British Royal Navy and his mother was reputed to have been a pawn broker or money lender.[12] He attended a seminary but did not join the priesthood. One of his brothers did become a priest, however, and one of his sisters became a nun. Dom enrolled at the University of Malta. He graduated with a Bachelor of Science and, later, as an architect and civil engineer (1937). That same year he was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship and pursued his studies at Hertford College, Oxford, where he earned a Masters in Science and Engineering in 1939.[12]

Political career

[edit]Early political career (1935–1949)

[edit]After a brief stint as an official of the Bormla Labour Party club, Mintoff was Labour's Secretary General between 1935 and 1945 (resigning briefly to pursue his studies abroad). He was first elected to public office in 1945 to the Government Council. In the same year, Mintoff was elected Deputy Leader of the Party with a wide margin that placed him in an indisputable position as the successor, if not a challenger, to party leader Paul Boffa. After Labour's victory at the polls in 1947, he was appointed Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Public Works and Reconstruction, overseeing large post-War public projects.[7]

Leader of the Labour Party (1949–1984)

[edit]

- First two mandates

Mintoff's strong position and ambition led to a series of Cabinet crises. A split in the Labour Party came about when Boffa, who was ready for compromise and moderation with the colonial authorities, resigned and formed the Malta Workers Party and Mintoff refounded the Labour Party as the "Malta Labour Party" of which he assumed leadership. The split resulted in the weakening of both parties and it was not until 1955 after remaining out of government for three consecutive legislatures, that the Labour Party was elected to office with Mintoff as Prime Minister. This government's main political platform – integration with the UK – led to a deterioration of the Party's relations with the Catholic Church, leading to interdiction by the Church which resulted in voting Labour being declared a mortal sin leading all who defied the Church to be informally known as "Suldati tal-Azzar" ("Soldiers of Steel"). The Labour Party lost the subsequent two elections in 1962 and 1966, and boycotted the Independence celebrations in 1964 due to disagreements with the Independence agreements which still gave a good amount of power to the British Government.[5]

Following the lift of the interdiction in 1964, and the improvement of relationship with the Catholic Church in 1969, Dom Mintoff was elected as Prime Minister when Labour won the 1971 general election and immediately set out to re-negotiate the post-Independence military and financial agreements with the United Kingdom. The government also undertook socialist-style nationalisation programmes, import substitution schemes, and the expansion of the public sector, the collective sector and the welfare state. Employment laws were revised with gender equality being introduced in salary pay. In the case of civil law, civil (non-religious) marriage was introduced and sodomy, homosexuality and adultery were legalised. Through a package of constitutional reforms agreed to with the opposition party, Malta declared itself a republic in 1974.[13] In 1979, the last British troops left Malta.[citation needed][14]

- Social and political troubles in the 1980s

The Labour Party was confirmed in office in the 1976 elections. In 1981, amid allegations of gerrymandering, the Party managed to hold on to a parliamentary majority, even though the opposition Nationalist Party managed an absolute majority of votes.[15] A serious political crisis ensued when Nationalist MPs refused to accept the electoral result and also refused to take their seats in parliament for the first years of the legislature. Mintoff called this action "perverse" but it was not an uncommon one in any parliamentary democracy with disputed election results. He proposed to his parliamentary group that fresh elections be held,[citation needed] but most members of his Parliamentary group rejected his proposal as it was likely that the prior result would be repeated.[citation needed] Mintoff stayed on as prime minister until 1984, during which time he suspended the work of the Constitutional Court during discussions with the Opposition to amend the Constitution.[16] He resigned as Prime Minister and Party leader aged 68 in 1984 (although he retained his parliamentary seat), opening the way for his deputy prime minister, Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici, to succeed him.[15]

For the 1981 elections, the opposition Nationalist Party, reinvigorated with a new leader and backed by various Conservative and Christian Democratic parties in Western Europe,[17] looked set for a serious challenge to Mintoff. In fact, in that election, the Partit Nazzjonalista managed an absolute majority of votes, but managed only 31 seats to the Malta Labour Party's 34. Mintoff said that he would not be ready to govern in such conditions and hinted that he would call for fresh elections within six months. However, pressure from party members forced Mintoff to do otherwise: Mintoff eventually accepted the President's invitation to form a government. This led to a political crisis whose effects continued through much of the 1980s characterised by mass civil disobedience and protests led by Opposition Leader Eddie Fenech Adami as well as increasing political violence, such as Black Monday.

Labour backbencher (1984–1998)

[edit]Mintoff resigned as Prime Minister and Leader of the Labour Party in 1984, while retaining his Parliamentary seat and remaining a government backbencher. He was succeeded by Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici. Mintoff was instrumental in convincing his parliamentary colleagues to support constitutional amendments ensuring a parliamentary majority for the party achieving an absolute majority of votes. A repeat of 1981 was thus avoided, and the Partit Nazzjonalista went on to win the 1987 elections. The Labour Party went into opposition for the first time in sixteen years. He successfully contested the 1992 and 1996 elections. However, there was a growing rift between Mintoff, seen as Old Labour, and Alfred Sant, the new Labour Leader. Things came to a head in 1998 when the Labour government was negotiating the lease of sealine to be developed in a yacht marina in Birgu. Mintoff eventually voted against the government's motion which was defeated. The Prime Minister saw this as a loss of confidence and The President, acting on Prime Minister Sant's advice dissolved Parliament and elections were held. This was the first time, since the war, that Mintoff's name was not on the ballot paper and the Malta Labour Party lost heavily.[18]

Foreign policy

[edit]

After Mintoff's initial attempts at integration with Great Britain proved unsuccessful he resigned in 1958 and became a strident advocate of decolonisation and independence.[19] Returning to office in 1971, he immediately set about renegotiating Malta's defence agreement with Britain.[19] The difficult negotiations with Britain, which later resulted in the departure of British forces in 1979 and the attendant losses in rent, were coupled with a policy of Cold War brinkmanship which saw Mintoff seek to play rivals off each other and look increasingly east and south, courting Mao Zedong, Kim Il Sung, Nicolae Ceaușescu and Muammar Gaddafi.[12]

Recently declassified CIA reports show the United States' fears that a Mintoff-led government in Malta could see the country fall under the Soviet sphere of influence.[20] Mintoff opposed Malta's EU and Eurozone membership on the concern for Malta's status as a constitutionally neutral country.[21]

Post-retirement (1998–2012)

[edit]After his retirement from parliamentary politics, Mintoff's involvement in public life was only occasional. He made some appearances in the referendum campaign on Malta's membership to the EU and, with Alfred Sant being replaced in 2008, some rapprochement with Labour was made.[citation needed]

Personal life

[edit]On 22 November 1947, Mintoff married Moyra de Vere Bentinck (11 July 1918 – 16 December 1997), daughter of Lt. Col. Reginald Bentinck, of Dutch and British noble lineage related via the Cavendish-Bentinck line to Queen Elizabeth II.[22][23][24][25] The couple wed at the parish church of Bir id-Deheb (Our Lady of Mercy), a tiny 19th century chapel on the outskirts of Żejtun. The chapel's rector was Canon Ġwann Vella, a friend of Mintoff.[26][27] They met during his studies in Oxford. The couple had two daughters, Anne and Yana. Yana, a member of the Socialist Workers Party, acquired brief notoriety in 1978 when she bombed the chamber of the UK House of Commons with manure in a protest against the British military presence in Northern Ireland.[15]

Death

[edit]Mintoff was taken to hospital on 18 July 2012.[28] He was later discharged on 4 August and spent his 96th birthday at home[29][30] where he died on 20 August.[31] He was given a state funeral by the Government of Malta on 25 August.[32]

Legacy

[edit]

While generations of loyal supporters continue to credit Mintoff with the introduction of social benefits like the children's allowance, two-thirds pensions, minimum wage and social housing as well as the creation of Air Malta, Sea Malta, the separation of church and state and ending 200 years of British colonial rule, critics point to his divisive legacy, and the violence and unrest that characterised his time in office. It has also been pointed out by Mintoff's critics that a pervasive cult of personality has been maintained after his death, most prominently within the Labour Party.

Mintoff's legacy in Malta is extremely apparent, being the longest-ruling Prime Minister in Maltese history, and overseeing the transition of Malta away from a British colony, to a socialist-aligned, neutral republic.[33][34] As such, the modern legal and societal structure of Malta were developed under the Labour government.

Mintoff was fundamental to the development of the Maltese constitution and the development of Maltese foreign policy, in which Malta was a member of the Non-Aligned Movement, and prioritised good relations with the second and Third World.[35][36] The modern system of nationalised health care in Malta was likewise created under Mintoff, as well as the modern Maltese housing system.[37][38] Mintoff is controversially also remembered as an authoritarian socialist that dominated the structure of the Maltese government.[39]

The economy of Malta, a relatively high income nation with a highly advanced welfare economy, and subsidies were devolved under Mintoff.[40] Under Mintoff, Language reforms saw an increase of schools teaching Maltese, which managed to revive the language from previous colonial-era decline.[41][42]

In 2013, the main square in front the church of Our Lady of Mercy in Bir id-Deheb, Żejtun (where Dom and Moyra Mintoff were married) was renamed Dom Mintoff Square.[43]

A statue of Mintoff was unveiled in his hometown Cospicua on 12 December 2014, designed by the artist Noel Galea Bason.[44]

In March 2016, Corradino Road (Maltese: Triq Kordin) in Paola was renamed Dom Mintoff Road (Maltese: Triq il-Perit Dom Mintoff).[45] Other roads were subsequently renamed in his honour in Bormla and Marsa. Another street named after Mintoff is located in the capital of Gozo, Rabat. In August 2016, a monument to Mintoff was unveiled in the Chinese Garden of Serenity in Santa Luċija.[46] Many plaques and monuments commemorating various anniversaries of his leadership of the Labour Party can be found around Malta, primarily near current or former Labour Party clubs.

In May 2018, a second statue of Mintoff was unveiled in Castille Square in Valletta directly opposite the office of the Prime Minister.[47][48]

In May 2019, a garden in Paola was renamed Dom Mintoff Garden after extensive rehabilitation works.[49] In August 2019, a hall was renamed after Mintoff in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in recognition of his contributions towards Maltese foreign policy.[50]

In June 2023, a third statue of Mintoff was unveiled by the Paola Local Council in Dom Mintoff Garden designed by renowned sculptor Alfred Camilleri Cauchi.[51][52]

Awards and honours

[edit]National honours

[edit] Companion of Honour of the National Order of Merit (1990) by right as a former Prime Minister of Malta

Companion of Honour of the National Order of Merit (1990) by right as a former Prime Minister of Malta Malta Self-Government Re-introduction Seventy-Fifth Anniversary Medal (1996)

Malta Self-Government Re-introduction Seventy-Fifth Anniversary Medal (1996) Malta Independence Fiftieth Anniversary Medal (2014) posthumous

Malta Independence Fiftieth Anniversary Medal (2014) posthumous

Foreign honours

[edit] Order of the Republic of Libya

Order of the Republic of Libya  (1971)

(1971) Grand Cordon of the Order of the Republic of Tunisia

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Republic of Tunisia  (1973)

(1973) Grand Cordon of the Order of Ouissam Alaouite

Grand Cordon of the Order of Ouissam Alaouite  (1978)[53]

(1978)[53]- Al-Gaddafi International Prize for Human Rights (2008)[54]

Biography

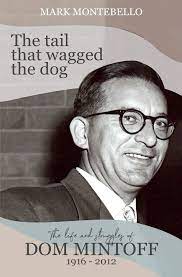

[edit]In May 2021 the first fully-researched biography of Mintoff was launched in Malta.[55] The Tail That Wagged The Dog: The life and struggles of Dom Mintoff (1916-2012), written and published in English by Mark Montebello, was issued by SKS Publications, a branch of Malta’s Labour Party,[56] which commissioned the book.[57] Though at first welcomed by Prime Minister Robert Abela, the leader of the party,[58] he later repudiated the biography,[59] though the book was not withheld from being sold by the publisher.[60] The vacillation was mainly due to Mintoff’s children disassociating themselves from the publication.[61][62][63] The author firmly stood by his work.[64][65] Seven years in the making,[66] the 640-page book was nonetheless positively hailed by critics,[67][68][69][70][71] and even shortlisted for the national book prize.[72]

References

[edit]- ^ Cyprus, Greece, and Malta. Britanncia Educational Publishing. 1 June 2013. ISBN 9781615309856. Retrieved 9 May 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Dom Mintoff. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Briguglio, Michael (October 2001). "3" (PDF). The Malta Labour Party in Perspective: 1920-87 (Sociology M.A.). University of Malta. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ Carmen Sammut (2007). Media and Maltese Society. Lexington Books. p. 35. ISBN 9780739115268. Retrieved 20 August 2012 – via Books.google.com.

- ^ a b "Dom Mintoff, Malta's political giant, passes away". Times of Malta. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ "Dom Mintoff". The Daily Telegraph. 21 August 2012. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Dom Mintoff, a dominant figure in Malta for 30 years, did great harm to his country". Catholic Herald. 22 August 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "CIA Files Show 20 Years Of Paranoia About Dom Mintoff". Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "Court finds in favour of National Bank shareholders". The Malta Independent. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ Mintoff, Dom. Mintoff Malta Mediterrra Żgħożiti (bil-Malti). Assoċjazzjoni Għall-Ġustizzja u l-Ugwaljanza u l-Paċi, & L-arkivji Nazzjonali. pg. 12.

- ^ Mercieca, Simon. "Il-Perit Duminku Mintoff u l-Immakulata (1916-2012".

- ^ a b c McFadden, Robert D. (20 August 2012). "Dom Mintoff, Proponent of Maltese Independence, Dies at 96". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ Philip Murphy, Monarchy and the End of Empire: The House of Windsor, the British Government, and the Postwar Commonwealth, OUP Oxford, 2013, pg. 157

- ^ Drury, Melanie. "Freedom Day in Malta: What's it all about?". GuideMeMalta.

- ^ a b c Patterson, Moira (21 August 2012). "Dom Mintoff obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ Ltd, Allied Newspapers. "How the Constitutional Court betrays Malta's Constitution". Times of Malta. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ Thuss, Holger; Bauer, Bence (9 May 2012). Students on the right way European Democrat Students 1961-2011 (PDF). Centre for European Studies. p. 104. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ "Malta changes its mind, again". The Economist. 10 September 1998. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Obituary: Dom Mintoff". BBC News. 21 August 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "The Outlook for an Independent Malta" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "Dom Mintoff: Pugnacious Prime Minister of Malta ..." The Independent. 23 August 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ Current World Leaders. International Academy at Santa Barbara. 9 May 1980. Retrieved 9 May 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Moyra de Vere Mintoff". geni_family_tree. 12 July 1917. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Charles Mosley, editor, Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage, 107th edition, 3 volumes (Wilmington, Delaware, U.S.A.: Burke's Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd, 2003), volume 3, page 3183

- ^ "Dom Mintoff". The Daily Telegraph. 21 August 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ "Dom in the flesh: carnal passions of the great socialist". MaltaToday.com.mt. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ "Tal-Hniena-Zejtun". Kappellimaltin.com (in Maltese). Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ^ "Dom Mintoff's health condition 'improved remarkably'". Malta Today. 26 July 2012. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ "Dom Mintoff discharged from Mater Dei Hospital on Saturday". gozonews.com. 5 August 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ Xuereb, Matthew (5 August 2012). "Mintoff to spend his 96th birthday quietly at home". Times of Malta. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ "Dom Mintoff, Malta's political giant, passes away". Times of Malta. 20 August 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "State funeral for Dom Mintoff". Times of Malta. 20 August 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ Lejn Malta Soċjalista: 'Il Quddiem fis-Sliem (in Maltese). Marsa: Partit tal-Ħaddiema. 1976.

- ^ Pirotta, Godfrey A. (21 August 1985). "Malta's foreign policy after Mintoff". The Political Quarterly. 56 (2): 182–186. doi:10.1111/j.1467-923X.1985.tb02350.x – via www.academia.edu.

- ^ Refalo, Charlton (2008) (21 August 2008). Malta's foreign relations during the Mintoff era, 1971-1984 (bachelorThesis). University of Malta – via www.um.edu.mt.

{{cite thesis}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Social Democracy in a Postcolonial Island State: Dom Mintoff's Impact" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Higher Education, Socialism & Industrial Development. Dom Mintoff and the 'Worker - Student Scheme'" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Dom Mintoff and Eddie Fenech Adami: Portraits of Persuasion and Charisma". Public Life in Malta. 1 January 2012 – via www.academia.edu.

- ^ Ideological and Strategic Shifts from Old Labour to New Labour In Malta, by Michael Briguglio

- ^ Dowdall, John (1 October 1972). "The political economy of Malta". The Round Table. 62 (248): 465–473. doi:10.1080/00358537208453048 – via Taylor and Francis+NEJM.

- ^ Frendo, Henry (21 August 1988). Maltese colonial identity : Latin Mediterranean or British Empire?. Mireva Publications. ISBN 9781870579018 – via www.um.edu.mt.

- ^ Camilleri Grima, Antoinette (21 August 2001). "The Maltese bilingual classroom : a microcosm of local society" – via www.um.edu.mt.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Proposal to name Żejtun street in Mintoff's honour". Times of Malta. 8 September 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ "Dom Mintoff's monument unveiled in Cospicua by Prime Minister Joseph Muscat". The Malta Independent. 12 December 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ "Corradino Road becomes Dom Mintoff Road, Gaddafi Gardens renamed". Times of Malta. 30 March 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Agius, Ritianne (7 August 2016). "Santa Luċija monument commemorates Dom Mintoff's centenary". TVM News.

- ^ "Rebel Priest Breaks Silence To Toast Dom Mintoff As His Monument Is Unveiled In Castille Square". Lovin Malta. 31 May 2018.

- ^ "Watch: Mintoff monument celebrates the future - Muscat". Times of Malta. 31 May 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Vassallo, Alvin. "Ġnien Duminku Mintoff in Paola inaugurated". TVM News. Television Malta. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ "Foreign Ministry hall named after Dom Mintoff". Times of Malta. 7 August 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Newsroom, T. V. M. (14 June 2023). "Dom Mintoff monument in Paola unveiled". TVMnews.mt. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Dom Mintoff statue inaugurated in Paola's Mintoff Gardens". Times of Malta. 14 June 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ "Dom Mintoff obituary". The Daily Telegraph. 21 August 2012. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ "List of recipients of the International Prize for Human Rights". algaddafi.org. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ "Dom Mintoff's biography launched". The Malta Independent. 19 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "SKS Publishers".

- ^ Vella, Matthew (8 May 2021). "Dimech biographer Mark Montebello pens Dom Mintoff biography". Malta Today. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ "Presentation of Mintoff's biography to the Prime Minister". SKS Publishers. 28 May 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Martin, Ivan (6 July 2021). "Labour pulls Dom Mintoff biography from its shelves". Times of Malta. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Vella, Matthew (7 July 2021). "Labour publisher SKS 'unaware of directive' to pull Mintoff biography". Malta Today. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Galea, Owen (6 July 2021). "Mintoff's children disassociate themselves from Fr Mark's biography of their father". TVM News. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ Bonnici, Julian (6 July 2021). "Dom Mintoff Daughters 'Disassociate' Themselves From Controversial Book On Malta's Former Prime Minister". Lovin Malta. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ "'Profoundly unethical and immoral': Mintoff's daughters blast new biography". Pressreader. 8 July 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ Vella, Matthew (8 July 2021). "Montebello defends Mintoff biography: 'I have no reason to lie'". Malta Today. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ Martin, Ivan (8 June 2021). "'I was asked to censor my book on Mintoff': Author of controversial biography defends his work after attack by family". Times of Malta. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ "Dom Mintoff biography that was seven years in the making officially launched". Times of Malta. 19 June 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ "La vita pubblica e quella privata del leader s'intrecciano con forza nella nuova biografia di Frate Mark Montebello". Corriere di Malta. 5 July 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "Mintoff's life and struggles as never seen before" (PDF). Maltese eNewsletter. May 2021. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Vella, Matthew (5 July 2021). "Dom in the flesh: carnal passions of the great socialist". Malta Today. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ "New biography highlights Mintoff's life and struggles as never seen before". Gozo News. 8 May 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ "Sex and socialism: Dom's bedroom secrets". Malta Today. 4 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Farrugia, Claire (2 August 2022). "Controversial Mintoff biography makes National Book Prize shortlist". Malta Today. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

External links

[edit]- U.S. Navy wanted to kill Mintoff, The Malta Independent, 26 January 2008.

- The New York Times report of his death, 21 August 2012.