Eden (2012 film)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

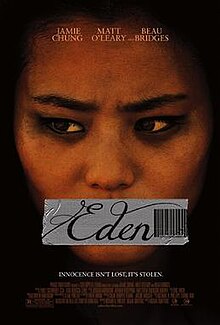

| Eden (Abduction of Eden) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Megan Griffiths |

| Screenplay by | Richard B. Phillips Megan Griffiths |

| Story by | Richard B. Phillips Chong Kim |

| Produced by | Colin Harper Plank Jacob Mosler |

| Starring | Jamie Chung Matt O'Leary Beau Bridges |

| Cinematography | Sean Porter |

| Edited by | Eric Frith |

| Music by | Jeramy Koepping Joshua Morrison Matthew Brown |

Production company | Centripetal Films |

| Distributed by | Phase 4 Films Cinema Management Group (International Sales Agent) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Eden (Abduction of Eden) is a 2012 American drama film about human trafficking. It was directed by Megan Griffiths, who co-wrote the screenplay with Richard B. Phillips and stars Jamie Chung, Matt O'Leary and Beau Bridges. The film was produced by Colin Harper Plank and Jacob Mosler through Plank's Centripetal Films production company. It was inspired by the story of Chong Kim, who claims that she was kidnapped and sold into a domestic human trafficking ring in the mid 1990s.[1][2][3] It had its world premiere at the 2012 South by Southwest Film Festival.[4]

Plot

[edit]Hyun Jae is an 18-year-old Korean-American girl living in New Mexico in 1994 with her immigrant parents. On a night out with a friend, Jae hits it off with a young firefighter at a bar, who offers to give her a ride. Jae later notices his badge is fake and attempts to escape, but is captured, bound, tapegagged and transported in the trunk of another car.

Jae is drugged and taken to an isolated warehouse, where her braces are removed, personal belongings taken away, and her captors putting a tracking anklet on her. Jae is introduced to Bob, a corrupt law enforcement official who was earlier shown killing two people in cold blood and who is the local leader of a sex trafficking ring, as well as his volatile, drug-addicted overseer, Vaughn. Bob informs Jae that he has information about her parents and that they will be harmed if she does not cooperate. He renames her Eden and gives her two days to adapt to her new life before she is forced to work. Eden endures daily pregnancy tests, being forced to star in pornographic films and being prostituted. During her first prostitution job, Eden attacks the client and tries to escape once again, but she's been recaptured, handcuffed and forced to stay overnight with her hands cuffed in a tub filled with ice. Vaughn is then confronted by Bob on the operation, resulting in him getting slapped.

One year passes, and Eden has adapted as much as possible to life in the operation and has befriended another girl named Priscilla, who is shocked to learn Eden is as old as she is (by now, almost 19). Priscilla tells Eden something unknown happens to girls who become "too old." Moments later, Priscilla herself is mysteriously taken away. Eden notices that Vaughn's trustee, a girl named Svetlana, has obtained the class ring she was given by her father the day of her abduction and makes an attempt to forcibly retrieve it from her until Vaughn and an enforcer pull her off. Vaughn forces Eden to swallow the ring, which she does, but Eden then volunteers to assist Vaughn in overseeing the operation, specifically with accounting. After working one night at a college fraternity party, Vaughn has Eden assist him in accounting from the frat brothers, and in recapturing two other girls who attempt to escape. Eden begins replacing Svetlana as Vaughn's trustee, answering phones and assisting with day-to-day operations, and is taken out of the sex work side of the operation.

Bob is shown leading a seminar on drug trafficking, but is questioned by detectives as he was placed by a GPS at the location of a missing deputy and landowner, the two people he killed earlier in the movie. Eden and Vaughn meet Bob later to dispose of bodies in the nearby lake, including Svetlana. Vaughn suddenly betrays Bob and brutally kills him on the boat, presumably because of his implication in the death of the deputy and landowner.

One day, while answering phones, Eden is taking a customer's order when the customer asks how much it will cost, which Eden knows is an indication that it is a police sting, but she takes the order anyway and says nothing. Eden and Vaughn take a girl to the house of a man named Mario, and Eden instantly recognizes him as the one who transported her to the warehouse in the trunk of his car. Eden goes to the bathroom and finds a room full of baby beds. She also finds Priscilla, who is heavily pregnant (why she was taken away, as she'd tested positive on one of the daily tests) and blissfully ignorant as to what will actually happen to her baby (he or she will be sold). Vaughn notices Eden being withdrawn on the way back, deduces that she found out what Mario's house is used for and attempts to force Eden to kill a girl in the desert to prove her loyalty, but she is stopped at the last minute by Vaughn.

Vaughn is informed that one of his enforcers have flipped on the operation, presumably because of Eden sending him to a sting. Eden is forced to start packing the girls for the move and is taken to Vaughn's house, where Vaughn informs her they are moving to Dubai. Eden realizes this could be her last chance to escape. While he is in the bathroom, she sprays Vaughn's meth pipe with chemicals that Vaughn inhales, killing him. Eden then cuts the tracking bracelet off her ankle, takes drugs and money from Vaughn's house, and goes to Mario's house. Eden attempts to negotiate Priscilla's freedom; Mario refuses but admits that he remembers Eden. He agrees to let her see Priscilla. While his back is turned, Eden injects Mario with drugs and kills him. Eden finds Priscilla, telling her her baby was sold, and they both escape the house. Eden finds a pay phone and calls her mother, hearing her voice for the first time in a year.

Cast

[edit]- Jamie Chung as Hyun Jae "Eden", an 18-year old Korean-American who is kidnapped and sold to human trafficking

- Matt O'Leary as Vaughan, a drug-addicted overseer of the trafficking ring and the main antagonist

- Beau Bridges as Bob, Vaughan's superior, a corrupt marshall and leader of the trafficking ring. He serves as the secondary antagonist of the film. Bridges also portrayed Clel Waller, another slave owner in the film adaptation of Nightjohn.

- Eddie Martinez as Mario, a customer who had Priscilla sold and was responsible for Hyun Jae's kidnapping

- Naama Kates as Svetlana, Vaughan's trustee

- Jeanine Monterroza as Priscilla, a girl who Eden befriends

- Scott Mechlowicz as Jesse, the person who kidnapped Eden in the beginning

- Tantoo Cardinal as The Nurse, a nurse of the operation

- Hillary Dominguez as Maria, one of the slaves

- Roman Roytberg as Ivan, one of Vaughan's henchmen

Production

[edit]Eden was produced by Centripetal Films and filmed in Washington State in the summer of 2011, with a largely local crew and funding assistance from Washington Filmworks, a government supported non-profit organization that provides financial support for films produced in Washington State. The idea for the film came into being when screenwriter Richard B. Phillips contacted Chong Kim after reading a newspaper article about her account of being sold into and escaping a domestic human trafficking ring. Phillips then proposed the idea of writing a screenplay based on Kim's story. Kim agreed, and the two of them set about writing a story for the film. That story was later turned into a screenplay by Phillips. Plank then hired Megan Griffiths to revise the script, and later hired Griffiths to direct the film.[3]

Critical reception

[edit]Eden has a score of 82% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 33 reviews.[5] Robert Abele of the Los Angeles Times said the film was "never less than suspenseful, but rather than sentimentally pander to easy outrage, or indulge in icky women-in-distress titillation, the movie...zeros in on the details of how dignity can be stripped like bark from a tree, and the queasy determination it takes to stay alive in a living hell."[6] Jeff Shannon from Seattle Times awarded the film with 3 out of 4 stars and said that "Cruelty, bloodletting and death are evident throughout (frequently occurring just outside the frame), and Griffith's laudable discretion actually intensifies their impact."[7] Stephen Holden of The New York Times said that "Enough films about human trafficking have been made in recent years that the outlines of Eden should be painfully familiar. But that familiarity doesn't cushion this movie's excruciating vision."[1] Along with Holden's review Eden was also selected as one of New York Times Critics' Pick.[1] Stephanie Carrie of the Village Voice said "overall, this is a powerful addition to the small collection of films dedicated to spreading awareness of this horrific crime."[8]

Many critics particularly praised the performance of Jamie Chung. Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian said that "a very strong performance from Chung impresses".[9] Matthew Turner of ViewLondon said "Chung duly steps up, delivering an emotionally complex performance that requires her to keep her true feelings closely guarded (we also see her distance herself from her work by adopting a different persona)" and ended by saying that it was a "terrific central performance from Jamie Chung".[10] Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic wrote "a quite moving performance comes from Jamie Chung as Eden, repulsion sliding into fearful acceptance without the extinction of hope."[11]

Some reviews were negative. Farran Smith Nehme of the New York Post called it "a Lifetime movie gone upscale-grindhouse" and criticized the South by Southwest festival's decision to give the film an award. Nehme also questioned the film's authenticity.[12] David Fear of Time Out said the film's second half "head[s] south of ludicrous, [and] Eden's goodwill dissipates." Fear also questioned the film's authenticity.[13]

Accusations of fraud

[edit]On June 4, 2014, the non-profit anti-trafficking organization Breaking Out announced on their Facebook page that, after a year-long investigation of Chong Kim and her life, they had "found no truth to her story. In fact, we found a lot of fraud, lies, and most horrifically capitalizing and making money on an issue where so many people are suffering from [sic]." Breaking Out also accused Kim of defrauding several organizations out of charitable donations and announced a coming lawsuit. Later that day, Griffiths commented on her Twitter account, "I just heard about this today and it came as a shock. I am deeply concerned about it."[14] Eden's official website claims that "A portion of the net profits from EDEN will benefit anti-slavery organizations."[15] Kim responded on her Facebook page, stating "I don't appreciate you spreading lies about me … Whatever you claim to have I have the right to see it otherwise I will send you and your organization a formal complaint."[16]

After these accusations arose, Noah Berlatsky of Salon compared Kim to Somaly Mam and commented that the film was thickly layered with exploitation tropes and improbable scenarios. Berlatsky found it shocking that "anyone took this clearly fanciful, clearly derivative fiction for fact".[17] Journalist Elizabeth Nolan Brown criticized "the authors who repeated Kim's story, the journalists who interviewed her, the organizations that brought her on as a speaker, or any of the myriad people behind the 'based on a true story' Eden" for not checking and verifying Kim's claims.[16] Journalist Mike Ludwig argued that the narrative promoted by the film harmed consensual sex workers.[18] Seattle sex worker Mistress Matisse had been questioning the veracity of the film since 2012.[14] Matisse stated that Colin Plank and Megan Griffiths "perpetrated a fraud in their movie called Eden."[19]

The Stranger journalist David Schmader had previously called the film a masterpiece and the best film ever made in Seattle,[20] but has since called its back story "bullshit."[14] Stranger writer Jen Graves was highly critical of Griffith's lack of research into Kim's story and regretted her initial support of the film. Since Breaking Out first made their allegations, Griffiths and others directly associated with the film have refused to comment further,[19] but the film's official website continues to promote the film as "Inspired by the harrowing true story of Chong Kim."[21] In 2012, Griffiths won the Stranger Film Genius Award. Charles Mudede, a Stranger writer and former winner of the award, wrote that Eden had "secured her nomination" and was "a masterpiece".[22]

On June 25, 2014 Kim's PR firm Bradshaw & Co. publicly denied the allegations and referenced a pending lawsuit.[23] Since its initial allegation, Breaking Out has continued to release information about Kim on their Facebook page, including court documents detailing Kim's 2009 felony charge of theft by swindle, for which Kim was ordered to pay $15,000[19] "to another human trafficking victim and activist in Minnesota."[18]

Awards and accolades

[edit]The film premiered at the 2012 South by Southwest film festival, where it won the Audience Award for Best Narrative Feature, Special Jury Recognition for Best Actress, Jamie Chung, and the award for Emergent Narrative Female Director, Megan Griffiths.[24]

It also won the Golden Space Needle Award for Best Actress, Jamie Chung and the Lena Sharpe Award for Persistence of Vision; Seattle Reel NW Award at the 2012 Seattle International Film Festival.[25]

It also won the Audience Award for Best Film at the 2012 San Diego Asian Film Festival.[26]

Release

[edit]Eden was released theatrically in North America by Phase 4 Films on March 20, 2013 at Film Forum in New York City.[27] It also played theatrically in Los Angeles and Seattle, followed by a release on VOD on April 20, 2013. It was released on DVD on June 11, 2013. The DVD and Blu-ray were released in the UK by Queensway Digital Ltd on September 9, 2013.[28]

A May 2013 screening in Seattle included a panel discussion about human trafficking sponsored by Hope for Justice and the World Affairs Council of Seattle, with panelists including Washington State senator Jeanne Kohl-Welles and YouthCare social worker Leslie Briner. Kohl-Welles had sponsored an anti-sex trafficking bill in the Washington State congress earlier that year[29] and would be a major supporter of the Motion Picture Competitiveness Bill.[30] Kohl-Welles and Griffiths were later panelists of the 2014 Seattle Film Summit, which called Kohl-Welles "the most vocal and reliable supporters of the State's film industry",[31] and Griffiths spoke at an October 2014 fundraiser in support of Kohl-Welles's re-election.[32][relevant?]

The international distribution rights were licensed by Cinema Management Group.[33]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Holden, Stephen (19 March 2013). "True Story Inspires Tale of Sex Trade; in a Twist, a U.S. Marshal Is the Bad Guy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Former sex slave shares story". The Ithacan. 29 March 2012. Archived from the original on 15 July 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ a b "Survivor of human trafficking and sex slavery on set for film shooting in Kirkland". Kirkland Reporter. 27 August 2011. Archived from the original on 11 August 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ "Eden". SXSW Schedule. Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ "Eden". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ^ Abele, Robert (28 March 2013). "Chilling look inside a sex ring called 'Eden'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ Shannon, Jeff (2 May 2013). "'Eden': a harrowing tale of sex trafficking". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ Carrie, Stephanie (20 March 2013). "Eden: A Chilling Account of a Horrific Crime". Village Voice. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (18 July 2013). "Eden – review". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ Turner, Matthew. "Eden Film Review". View London. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ Kauffman, Stanley (27 March 2013). "Reality, Eden and The Silence". The New Republic. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ Nehme, Farran Smith (22 March 2013). "'Eden' review". New York Post. Archived from the original on 27 November 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ Fear, David (19 March 2013). "Eden: movie review". Time Out New York. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Schmader, David (4 June 2014). "Chong Kim, the Woman Whose Allegedly True Story Served as the Basis for Megan Griffith's Film Eden, Denounced as a Fraud". The Stranger. Archived from the original on 29 August 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "See the movie Eden and help put an end to human trafficking". Eden. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014.

- ^ a b Brown, Elizabeth Nolan (12 June 2014). "Another High-Profile Sex Trafficking Tale May Be Falling Apart". Reason. Archived from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- ^ Berlatsky, Noah (4 June 2014). "Hollywood's dangerous obsession with sex trafficking". Salon. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ a b Ludwig, Mike (9 July 2014). "From Somaly Mam to Eden: How Sex Trafficking Sensationalism Hurts Sex Workers". Truthout. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ a b c Graves, Jen (17 December 2014). "Eden Was a Scary Movie About Sex-Trafficking Based on a True Story—Or Was It?". The Stranger. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ Schmader, David (1 May 2013). "Real-World Horror, Film-World Triumph". The Stranger. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ "The Story of EDEN". Eden. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ Mudede, Charles. "Geniuses - The Stranger's Genius Awards". The Stranger. Archived from the original on 2014-12-29. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- ^ "Chong Kim, former human sex trafficking victim is victimized again". PRLog Press Release Distribution. Archived from the original on 2014-12-29. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- ^ "Film News - SXSW 2014". SXSW. Archived from the original on 10 August 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ "SIFF 2012 Award Winners". SIFF.net. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-14.

- ^ "2012 SDAFF Recap". Pacific Arts Movement. 3 November 2012. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ "EDEN - Movies". Film Forum. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ "Product Detail". Archived from the original on 3 January 2014.

- ^ "SIFF to host 'Eden' panel discussion". Magnolia News. 3 May 2013. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ "Tax Incentives Archives". Media Inc. Archived from the original on 2014-10-31. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- ^ "Featured Panelists". seattlefilmsummit.com. Archived from the original on 2014-12-29. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- ^ "Film Community Fundraiser for Senator Jeanne Kohl-Welles!". 36th.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- ^ "CMG adds SXSW audience award winner Eden to Cannes slate". Screen Daily. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2012.