Faik Pasha Mosque

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Faik Pasha Mosque Φαΐκ Πασά Τζαμί | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| District | Arta |

| Province | Epirus |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Closed |

| Location | |

| Location | Arta, Greece |

| Municipality | Arta |

| State | Greece |

| Geographic coordinates | 39°09′57″N 20°58′22″E / 39.16583°N 20.97278°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Mosque |

| Funded by | Faik Pasha |

| Completed | 15th century |

| Specifications | |

| Dome(s) | 1 |

| Minaret(s) | 1 (half-destroyed) |

| Materials | Brick and stone |

Faik Pasha Mosque (Turkish: Faik Paşa Camii, Greek: Τζαμί Φαΐκ Πασά), also known locally as the Imaret of Arta (Ιμαρέτ της Άρτας), is a historical Ottoman building located in the town of Arta, Epirus, in Greece. Named after the Ottoman conqueror of the city in 1449, the mosque formed a complex including baths, an imaret and a madrasa. It is one of the two surviving mosques in Arta, the other being the Feyzullah Mosque. It is under renovation works and is not currently open for worship.

Location

[edit]Faik Pasha Mosque is located in the ancient locality of Marati[1][2] near the village of Marathovouni, on the right bank of the Arachthos river and about 1.5 km north of the Bridge of Arta. During the Ottoman era, the area surrounding the edifice bore the general name of Top-Alti, a Turkish term describing the sector which was within cannon range of the castle of Arta.[3][4] More specifically, the traveler Evliya Çelebi mentioned the Muslim village of Karye-i Imaret,[5] from which derives the Greek toponym Marati.[1]

History

[edit]Ottoman Era

[edit]

The Faik Pasha Mosque was probably erected on the site of an earlier Byzantine church dedicated to Saint John the Baptist.[6][7] Its sponsor was Faik Pasha, conqueror of the city[8] and an Ottoman vizier,[9] hence the mosque's name. Two dating hypotheses exist; the first, formulated by the Metropolitan of Arta Seraphim of Byzantium, dates the building back to around 1455. According to oral tradition collected in the middle of the 18th century from an Ottoman inhabitant, Faik Pasha appointed an imam for the mosque but upon his death, not finding a worthy replacement, the pasha decided to retire from the army and take on the role of the imam himself. Faik Pasha is said to have remained imam for about forty years, until his death in 1499. Based on this information, the Metropolitan of Arta dated the construction of the mosque to the time of Sultan Mehmed II the Conqueror.

The second hypothesis places the construction of the mosque in 1492-1493, during the reign of Bayezid II.[10][11][12] This dating appears more plausible than the previous conjecture, insofar as the Ottoman historian Aşıkpaşazade referred around 1478 to the mosque as being in draft form and that the founding charter (wakf) of Faik Pasha's institution, including an imaret and a madrasa, dates from 1493.[5][11]

The institution derived its income from agricultural land in the villages of Vigla and Marati, which belonged to the Monastery of Panagia of Rhodia before the Ottoman rule of Epirus,[13] as well as from properties near the cities of Thessaloniki and Yenice, modern Giannitsa.[5]

During the Greek War of Independence in 1821, the area became the scene of fighting during the siege of Arta. The mosque was an entrenchment camp for Giannis Makrygiannis, Markos Botsaris and a few hundred men, who resisted the assaults of the Ottoman garrison on November 12, 1821.[14][15][12] A few years later, the place was visited by François Pouqueville, who highlighted the presence of Persian reeds, olive trees, lemon trees and orange trees,[16] while in 1835 William Martin Leake described it as rich in hazel trees.[17]

During the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, the area around the mosque became once again a battleground between the Greek forces of Colonel Thrasyvoulos Manos and the Ottoman forces of Ahmed Hifzi Pasha.[18]

Greece

[edit]After the annexation of Arta by the Kingdom of Greece in 1881 following the Convention of Constantinople, the mosque was briefly converted into a Christian church dedicated to Saint John the Russian.

In 1938, the building was declared a protected historic monument by royal decree.[19] In 1994, excavations led to the discovery of several architectural portions of the porch and restoration work led to the rehabilitation of the paved floor.[20] By the end of 2019, the studies for the general restoration of the monument were approved by the Central Archaeological Council[21] and the work was finally put up for auction in the summer of 2022.[22] The site is under the responsibility of the 8th Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities of the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports.[8]

Architecture

[edit]

The Faik-Pasha mosque consists of a square praying hall with external dimensions of 11.5 m per side, surmounted by a dome[2] whose drum is decorated with "Turkish triangles".[23] On the main facade, facing the north, there once stood a porch (revak), the remains of which are still visible to this day. Constructed as a partitioned apparatus,[24] the masonry incorporates certain materials from the Byzantine church of the Panagia Paregoretissa[17][25] from the ancient city of Nicopolis, as well as from various ancient buildings in the city of Ambracia (ancient Arta).[26] Materials of the now collapsed porch came from the nearby monastery of Panagia Pantanassa, founded in the middle of the 13th century by Michael II Doukas.[27] At the north-west corner stands the cylindrical minaret made of brick, preserved up to the balcony,[2] probably rebuilt for the last time in the 19th century.[28] Inside, the monument retains traces of its dual use as a mosque and a church: the mihrab occupies the center of the southern wall while the remains of the iconostasis can be seen on the eastern wall.[29]

Apart from the mosque, the remains of the baths located a few dozen meters to the northwest are the only traces that have come down to us of the monumental complex of Faik Pasha.[29]

Gallery

[edit]- Faik Pasha Mosque

- Distant view of the mosque from the west.

- Interior of the mosque from the northwest.

- Photograph of Machiel Kiel in the 1970s.

- The minaret at the northwest corner.

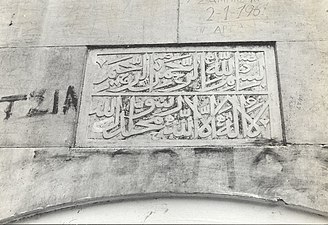

- Detail of the dedicatory inscription.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Lowry 2009, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b c Afendra Moutzali (2011). "Άρτα: Οι μεταμορφώσεις του αστικού τοπίου" [Arta: The Transformation of the urban cite]. Archéologie et Arts. 112: 73–81. ISSN 1108-2402.

- ^ Veikou, Myrto (2012). Byzantine Epirus: A Topography of Transformation. Settlements of the Seventh-Twelfth Centuries in Southern Epirus and Aetoloacarnania, Greece. Brill Publications. p. 409. ISBN 978-90-04-22151-2. Retrieved December 22, 2021.

- ^ Seraphim of Byzantium 1884, p. 378.

- ^ a b c Eyice 1995, p. 103.

- ^ Seraphim of Byzantium 1884, p. 147.

- ^ Papadopoulou & Tsiara 2008, p. 61.

- ^ a b Mikropoulos 2008, p. 446.

- ^ Eyice 1995, p. 102.

- ^ Ameen 2017, p. 22.

- ^ a b Lowry 2009, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b Kiel, Machiel (2001). "Karlı-ili. Batı Yunanistan'da bir Osmanlı sancağı" [Province of Karli-eli: An Ottoman sanjak in Western Greece]. Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Vol. 24. pp. 499–502.

- ^ Seraphim of Byzantium 1884, pp. 172, 328.

- ^ Kitromilides, Paschalis M.; Tsoukalas, Constantinos (2021). The Greek Revolution: A Critical Dictionary. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-674-25931-7.

- ^ Detsikas, Kostas (2005). Καραϊσκάκης. Ο στρατάρχης [Karaiskakis: The Marshal] (in Greek). Athens: Heliotrópio. pp. 174–175. ISBN 9789603423706.

- ^ Pouqueville 1824, p. 308.

- ^ a b Leake 1835, p. 218.

- ^ von Strantz 1898, p. 224.

- ^ "Διαρκής Κατάλογος των Κηρυγμένων Αρχαιολογικών Χώρων και Μνημείων της Ελλάδας" [Permanent list of declared archaeological sites and monuments of Greece]. www.listedmonuments.culture.gr (in Greek). Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2021.

- ^ Archaiologikē Hetaireia 1994, p. 51.

- ^ "The study for the restoration of the Imaret Mosque of Arta has been approved". archaeology.wiki. November 18, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ Váso Górou (June 28, 2022). "Άρτα: Δημοπρατείται η αποκατάσταση του Ιμαρέτ" [Arta : The restoration of the Imaret is put in auction]. www.ertnews.gr (in Greek). Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ Kiel 1972, p. 326.

- ^ Kontogiannis 2014, p. 54.

- ^ Moutzali 2008, p. 184.

- ^ "Δήμος Αρταίων" [Municipality of Arta]. www.arta.artinoi.gr (in Greek). Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ Archaiologikē Hetaireia 1994, p. 121.

- ^ Kontogiannis 2014, p. 55.

- ^ a b Kontogiannis 2014, pp. 58–59.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ameen, Ahmed (2017). Islamic architecture in Greece: Mosques. Alexandria: Center for Islamic Civilization studies, Bibliotheca Alexandrina.

- Archaiologikē Hetaireia (1994). To Ergon tes Archaiologikēs Hetaireias (in Greek). Vol. 149. Archaiologikē Hetaireia.

- Büktel, Yılmaz (November 2016). "Arta – Narda Osmanlı Hatıraları" [Arta – Ottoman Souvenirs of Arta]. In Taş, Ela; Işık Yayla, Rumeysa; Alkan, Murat (eds.). Proceedings of the XXth International Symposium of the Medieval and Turkish Era Excavations and Art History Researches (in Turkish). ISBN 978-605-4735-93-8.

- Değerli, Ayşe (2019). "Fatih Devri Vezirlerinden Faik Paşa'nın Vakfiyesi" [The Charter of Faik Pasha, one of the Viziers of the Conquest Era] (in Turkish). 2. Karatay Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi. ISSN 2651-4605.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Eyice, Semavi (1995). "Fâik Paşa Camii". Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Vol. 12.

- Eyice, Semavi (1968). "Yunanistan'da Unutulmuş bir Türk Eseri: Narda'da Faik Paşa Camii" [A Forgotten Turkish monument in Greece : the Faik Pasha Mosque of Arta] (in Turkish). 5. Belgelerle Türk Tarih Dergisi. ISSN 0041-4247.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Lowry, Heath W. (2009). Ottoman Architecture in Greece. A Review Article With Addendum & Corrigendum. Istanbul: Bahçeflehir University Press. ISBN 978-975-6437-88-9.

- Kiel, Machiel (January 1, 1972). "Yenice Vardar (Vardar Yenicesi-Giannitsa)". Studia Byzantina Et Neohellenica Neerlandica. Brill publications. ISBN 978-90-04-03552-2.

- Kontogiannis, Evangelos (2014). Ιμαρέτ: Στη σκιά του ρολογιού. Ιμαρέτ-Φεϋζούλ: Επαρμηνεύοντας τα τεμένη της Άρτας [In the shadow of the clock. Feyzullah Imaret: Interpretation of the mosques of Arta (bachelor's thesis from the National Polytechnic University of Athens)].

- Leake, William Martin (1835). Travels in Northern Greece. Vol. I. London: J. Rodwell.

- Mikropoulos, Tasos (2008). Elevating and Safeguarding Culture Using Tools of the Information Society: Dusty traces of the Muslim culture. Ioannina: Earthlab. ISBN 978-960-233-187-3.

- Moutzali, Afendra (2008). Faik Pasha Mosque (or Imaret) in Ottoman architecture in Greece. Translated by Elizabeth Key Fowden for Greek. Athens: Ministry of Culture and Sports. ISBN 978-960-214-792-4.

- Papadopoulou, Varvara; Tsiara, Aglaia (2008). Εικονες της Αρτας: η εκκλησιαστικη ζωγραφικη στην περιοχη της Αρτας κατα τους Βυζαντινους και μεταβυζαντινους χρονους [Icons of Arta: the ecclesiastic painting in Arta during the Byzantine and post-Byzantine period] (in Greek). Metropolis of Arta. ISBN 978-960-98053-0-8.

- Pouqueville, François (1824). Firmin Didot (ed.). Histoire de la régénération de la Grèce : comprenant le précis des évènements depuis 1740 jusqu'en 1824 (in French). Vol. III. Paris.

- Seraphim of Byzantium (1884). Δοκίμιον ιστορικής τινος περιλήψεως τής ποτε αρχαίας και εγκρίτου Ηπειρωτικής πόλεως Άρτης και της ωσαύτως νεωτέρας πόλεως Πρεβέζης [Essay on historical summary of the once ancient and esteemed Epirotan town of Arta and also the newer town of Preveza] (in Greek). Athens: Kállous.

- von Strantz, Viktor (1898). The Greco-Turkish War of 1897: From Official Sources. London: Swan Sonnenschein.

External links

[edit] Media related to Faik Pasha Mosque at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Faik Pasha Mosque at Wikimedia Commons