Giuseppe Francesco Borri

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Giuseppe Francesco Borri (4 May 1627 in Milan – 20 August 1695 in Rome) was an alchemist, prophet, freethinker, physician and eye doctor.

Education

[edit]His mother, Savinia Morosini, died giving birth to him. His father, Branda Borri, was a distinguished doctor with a great passion for chemical experiments. He claimed to be a descendant of Sextus Afranius Burrus; his uncle Cesare was a professor in law in Pavia.[1] In 1644, together with his brother, Borri entered a Jesuit seminary in Rome. There he was taught by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher, who had an important influence on him. His intolerance of ecclesiastical authority deteriorated his relationship with his teachers Sforza Pallavicino and Théophile Raynaud (Borri even led a collective rebellion of seminarists, provoking the replacement of Nicola Zucchi, the Rector, who was dismissed). In 1649/50 Borri was expelled from the seminary as he had problems with the idea of the Immaculate Conception.[2] He started his activity as a physician and alchemist among the pilgrims flocking to Rome for the Holy Year. In this period he met the Marquis Massimiliano Palombara, himself an alchemist, and in 1653 he took service with Federico Mirogli, as physician and alchemist. The year after he was involved in a fight, forced to seek asylum and had a vision.[3]

Prophecy

[edit]Borri began his propaganda, both messianic and political, with the purpose of returning to an evangelically pure religion. Borri believed religion to be the foundation of every science and scientific investigation. For him the whole world (Christian and non-Christian) should be conquered and ruled by a papal theocracy, that should trailblaze the Kingdom to come: a sort of heavenly world, a new Golden Age, where the values of a renewed and universal Christianity would triumph. Borri considered himself (at least according to the later Inquisition's records) Prochristus, the prophet and herald of the new era.

The Court of Queen Christine of Sweden

[edit]In 1655, Borri met Queen Christine of Sweden and probably frequented her court. In a cabinet transformed into a laboratory, the very learned Christine gave hospitality to alchemists and cabalists of different value and provenance. During the Naples Plague (1656) almost half of the population died within two years.[4] When the plague broke out in Rome, Borri provided his clients with camphor.[5] Christine fled to France; Borri went back to his hometown, Milan.

Legend

[edit]

According to the legend, handed down in 1802 by scholar Francesco Cancellieri, one morning in 1657, a stranger was caught gathering herbs in the garden of Marquis Massimiliano Palombara. He was brought to the Marquis by the servants. He declared himself to be an alchemist, to have knowledge of the Marquis' alchemical researches and to be able to show him the feasibility of transmutational work, without any request or reward, and to be interested in knowing Palombara's methods and researches.

The unknown stranger, after having performed various operations under Palombara's eyes, asked for hospitality in a room near the laboratory, to be able to watch over his work; then he asked the Marquis to give him the keys to the laboratory, promising that he would explain everything to the Marquis after having completed his work; but for the moment he needed solitude and peace.

Early next morning, Palombara knocked in vain at the laboratory's door, and then at the pilgrim's room. During the night, the latter had sneaked away through a window, leaving in the adjoining laboratory only an upside-down crucible and, on the floor, a streak of gold, and a sheaf of papers covered with notes and hermetic symbols on the Great Work. Palombara ordered these symbols to be carved in several places in his mansion, and on the famous Porta Alchemica, the only surviving feature of the Villa Palombara. The mysterious alchemist was claimed to be Borri.

Milanese affair

[edit]

In Milan, Borri contacted the Palagians Quietist milieu, which was widely scattered in Lombardy, and centred on Saint Pelagio's church and the prophetic charisma of Giacomo Filippo Casola, a layman who was accused of heresy by the Inquisition and shortly after died in jail. Very soon Borri became the figurehead of the Milanese movement and the fervour generated by his predication culminated in a public gathering in the square of Milan cathedral in 1658.

He was prosecuted for heresy and poisoning (the latter accusation refers to his alchemical knowledge). Meanwhile, the Inquisition arrested his followers, mostly low clergymen, many of them as young and fervent as Borri. In 1659, he was called before the Roman Inquisition, while the Milanese Inquisition was still prosecuting his followers. He was gagged, handcuffed, and dragged away.

He fled to Innsbruck and met with Rocco Mattioli. He was sentenced by default and informed of the public abjuration of his Milanese followers. After his father died, the inquisitor in Milan tried to take possession of Francesco's inheritance. The civil authorities acted with firmness, and secured the passage of the whole of the estate to his brother Cesare.[6]

Fame

[edit]

Via the Free City of Augsburg Borri moved to free imperial city Strasbourg, where the Protestant milieu welcomed him with enthusiasm. Borri was surrounded by a circle of fervent admirers, who glorified his ability as a physician, ophthalmologist and iatrochemist. Soon he became well known among the local noblemen, and his fame spread. He seems to have visited Frankfurt, Leipzig and Dresden, and in December 1660, he arrived in Amsterdam.

Meanwhile, after the verdict was read in public, Borri's effigy was brought in procession to Campo de' Fiori in Rome, where 60 years earlier, Giordano Bruno had been executed. The effigy was hung and burned together with Borri's writings.

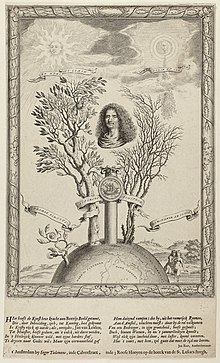

Princes and merchants flocked to consult the physician-alchemist, who specialized on cataract. He extended his interests beyond medicine and alchemy to include magic, cosmetics, and engineering. In April 1661, the Amsterdam burgomasters conferred on him honorary citizenship. During this period, he met Henry Oldenburg, Robert Moray, Constantijn Huygens, Franciscus van den Enden, Theodor Kerckring and Olaus Borrichius, then living in Amsterdam for his studies. Borrichius who became an admirer of Borri and his knowledge. Borri even dedicated to Borrichius a book (Chymie Hippocraticae Specimina Quinque, Köln, 1664). He was portrayed by Jürgen Ovens and engraved by Pieter van Schuppen.[7]

In Amsterdam Borri cut open the eye of a dog, expressed the lens together with the aqueous and vitreous body, instilled a liquid and showed that the eye regained its shape and the humors were reformed. He later repeated his experiment in Copenhagen on a goose.[8]

In April 1662 Borri borrowed 100,000 guilders from Gerard Demmer, a former Council of the Dutch Indies who had served the East India Company on Ambon Island, and in turn supplied him with his secret treatment.[9] Borri promised to pay back the money after two years. But Demmer died within a few days (and was buried on 5 May). Borri rented a mansion with stables and drove around in a coach. He was attended by six servants and kept a tiger in his house.[10] When Borri did not pay back anything after two years, Demmer's heirs started a trial. In January 1665 he was obliged in a verdict. Either already in 1664, but before 17 December 1665 Borri left Amsterdam, taking with a large sum of money and jewels. In 1667 he was visiting Rudolf August of Brunswick and then Hamburg.

Arrest and death

[edit]Borri sought refuge in Copenhagen as an alchemist at Frederick III's court, which subsidised him liberally. In Denmark, Borri had many friends and helpers like Caspar Bartholin the Younger and was preceded by his solid reputation as a scientist. Meanwhile, other subsidies came from the former Queen Christina, then residing in Hamburg, interested in the mysteries of the Philosopher's Stone. Borri regained fame and honours, becoming a trusted councillor to the king.

According to Michael White in Isaac Newton: The Last Sorcerer, Sir Isaac Newton attempted to contact Borri in 1669, through Newton's friend Francis Ashton. At the height of his fame, Borri's luxurious lifestyle left him penniless.

In 1670, when Christian V ascended to the throne, Borri's fortunes again began to decline, and he resolved to leave Denmark and to move to Ottoman Empire. While journeying, he was arrested in Goldingen, Moravia or the Carpathian Mountains, and thanks to pontifical pressure, was given by Leopold I, Emperor of Austria, into the hands of the Vatican.

Sentenced to life in prison on 25 September 1672, Borri, like his followers, was forced to perform a public act of abjuration and atonement. Borri stayed in jail until 1678. His noble friends (in particular the French ambassador, the Duke of Estrées, who was healed by Borri under a papal dispensation that permitted him to visit the sick nobleman in his mansion palazzo Farnese) obtained for him a sort of semi-liberty. In 1689 Christina of Sweden died, and the new Pope Innocent XII revoked the privileges granted to Borri. From 1691 Borri was under house arrest in Castel Sant'Angelo, where he furnished a laboratory to continue his studies, and was able go out to practise his art in the mansions of his noble friends, the prince Borghese and Borromeo.

In this period he met again his old friends and despite captivity, he regained his reputation as a healer and thaumaturge in the Roman court. Having caught a malaria, the great physician had prescribed himself quinquina's bark, the most advanced cure then available. But the bark was not available in Rome, and arrived too late, and on 16 August 1695, Borri died at the age of 68.

Works

[edit]- Lettere di F. B. ad un suo amico circa l’attione intitolata: La Virtù coronata. Roma 1643

- Gentis Burrhorum notitia. Argentorati 1660

- Iudicium....de lapide in stomacho cervi reperto. Hanoviae 1662

- Epistolae duae, 1 De cerebri ortu & usu medico. 2 De artificio oculorum Epistolae duae Ad Th. Bartholinum. Hafniae 1669

- La chiave del Gabinetto del Cavagliere G. F. Borri. Colonia (Geneva) 1681

- Istruzioni politiche date al re di Danimarca. Colonia (Geneva) 1681

- Hyppocrates Chymicus seu Chymiae Hyppocraticae Specimina quinque a F. I. B. recognita et Olao Borrichio dedicata. Acc. Brevis Quaestio de circulatione sanguinis. Coloniae 1690

- De virtutibus Balsami Catholici secundum artem chymicam a propriis manibus F. I. B. elaborati. Romae 1694

- De vini degeneratione in acetum et an sit calidum vel frigidum decisio experimentalis in Galleria di Minerva, II, Venezia 1697

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Salvatore Rotta - Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 13 (1971)

- ^ Salvatore Rotta - Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 13 (1971)

- ^ Salvatore Rotta - Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 13 (1971)

- ^ Scasciamacchia, S; Serrecchia, L; Giangrossi, L; Garofolo, G; Balestrucci, A; Sammartino, G; Fasanella, A (2012). "Plague epidemic in the Kingdom of Naples, 1656-1658". Emerg Infect Dis. 18 (1): 186–8. doi:10.3201/eid1801.110597. PMC 3310102. PMID 22260781.

- ^ Salvatore Rotta - Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 13 (1971)

- ^ Salvatore Rotta - Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 13 (1971)

- ^ "Portret van Giuseppe Francesco Borri, Pieter van Schuppen, naar Jürgen Ovens, 1675".

- ^ KOCH, HANS-REINHARD, and KONRAD R. KOCH. “Borri, the Prophet, on the ‘Restitutio Humorum’ and on Lens Aspiration in the 17th Century / Der Prophet Borri Über Die ‘Restitutio Humorum’ Und Die Linsen-Aspiration Im 17. Jahrhundert.” Sudhoffs Archiv, vol. 101, no. 2, 2017, pp. 160–83. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26385714. Accessed 2 Dec. 2022.

- ^ De regeeringe van Amsterdam, soo in 't civiel als crimineel en militaire (1653-1672) by Hans Bontemantel, p. 473-474

- ^ Francesco Giuseppe Borri: wonderdokter uit Milaan by Maarten Hell

Bibliography

[edit]- G. Cosmacini, Il medico ciarlatano. Vita inimitabile di un europeo del Seicento, Laterza, Bari 2001.

- P. Bornia, La porta magica di Roma. Studio storico, Phoenix, Genova 1983

- L. Pirrotta, La porta ermetica, un tesoro dimenticato, Atanòr, Roma 1979

- Alkymisten Borri ved Frederik III's Hof by Aug. Fjelstrup In: TIDSSKRIFT FOR INDUSTRI 1905

External links

[edit]- Marra, Massimo. "Giuseppe Francesco Borri, between Crucibles and Salamanders". www.alchemywebsite.com. Translated by Carlo Borriello.