Hamsa-Sandesha

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Hamsa Sandesha | |

|---|---|

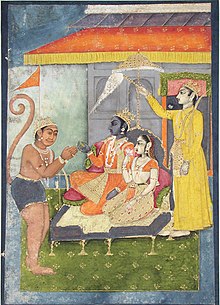

Painting of Rama and Sita, the central characters of the poem. | |

| Information | |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Author | Vedanta Desika |

| Language | Sanskrit |

| Verses | 110 |

| Hamsa Sandesha | |

|---|---|

| The Swan's message | |

| by Vedanta Desika | |

| Original title | हंससन्देश |

| Written | 13th century |

| Country | India |

| Language | Sanskrit |

| Subject(s) | Rama's love for Sita |

| Genre(s) | sandeśa kāvya (messenger poem) |

| Meter | mandākrāntā |

| Lines | 110 verses |

The Hamsa Sandesha (Sanskrit: हंससन्देश; IAST: Hamsasandeśa) or "The message of the Swan" is a Sanskrit love poem written by Vedanta Desika in the 13th century CE. A short lyric poem of 110 verses, it describes how Rama, hero of the Ramayana epic, sends a message via a swan to his beloved wife, Sita, who has been abducted by the demon king Ravana. The poem belongs to the sandeśa kāvya "messenger poem" genre and is very closely modeled upon the Meghadūta of Kālidāsa.[1] It has particular significance for Sri Vaishnavas, whose god, Vishnu, it celebrates.

Sources

[edit]The Hamsa-Sandesha owes a great deal to its two poetic predecessors, Kālidāsa's Meghadūta and Valmīki's Ramāyana.[2] Vedanta Desika's use of the Meghaduta is extensive and transparently deliberate;[a] his poem is a response to one of India's most famous poems by its most celebrated poet. Vedanta Desika's debt to Valmīki is perhaps more pervasive but less obvious, and possibly less deliberate too. Where the poet consciously plays with Kalidasa's verse, he treats the Ramayana more as a much-cherished story. Nevertheless, he is clearly as familiar with the details of Valmiki's poem as with Kalidasa's, and he echoes very specific images and details from the epic.[b]

The poet

[edit]Vedanta Desika (IAST:Vedānta Deśika) is best known as an important acharya in the Srivaishnavite tradition of South India which promulgated the philosophical theory of Viśiṣṭādvaita. He was a prolific writer in both Tamil and Sanskrit, composing over 100 philosophical, devotional and literary works; the Alagiya-Sandesha is his only work of this kind.

Vedanta Desika was born in 1269 CE. One popular story about his birth and childhood runs as follows: His devout parents were childless. One day they were visited in two separate but simultaneous dreams in which they were instructed to go to Tirupati, an important pilgrimage spot in south India, where they would be given a son. Once there, his mother had another dream in which she gave birth to Venkatesha's (the god of Tirupati) ghaṇṭa (bell). The next day the temple bell was missing and the chief priest, who had also had a visitation, celebrated the imminent birth of a child sent by the lord. Twelve years later, Veṇkaṭeśa was born, the ghaṇṭa-avatāra (incarnation of the bell) who later became best known as Vedanta Desika (an honorific which literally means "guide for the Vedanta").[3] A talented child, he amazed the senior priests at the age of five and proclaimed that he had learnt all there was to know by 20.

Vedanta Desika was the chief acharya of Kanchi (now Kanchipuram in Tamil Nadu), the centre of the northern Srivaishnavite community, but later went to live in Srirangam (a town near Trichy in southern Tamil Nadu), the centre of the southern Sri Vaishnavas. He died at Srirangam in 1370, having returned to the city after its re-capture by Hindus following a Muslim sack. Vedanta Desika's intent of writing such a poem was to attract readers of Sanskrit literature towards Sri Vaishnava philosophy by using this poem as a medium of introducing Sri Vaishnava concepts in the poem.

Structure of the text

[edit]The poem is divided into two clear parts, in line with Kalidasa's Meghaduta. The first half, of 60 stanzas, describes how Rama sights and engages the swan as his messenger,[4] and then describes to the swan the route he should take and the many places – primarily holy spots - he ought to stop on the way.[5] The second part begins in Lanka where the poet introduces us to the ashoka grove where Sita is being held,[6] the śiṃṣūpa tree beneath which she sits,[7] and finally Sita herself in a string of verses.[8] The actual message to Sita consists of only 16 verses,[9] after which Rama dismisses the swan and the narrator completes the story of the Ramayana. The poem ends with an autobiographical note by the poet.[10]

Alagiya

[edit]The messenger in this poem is referred to as a rājahaṃsa' ('royal haṃsa).[11] According to Monier-Williams, a haṃsa is a "goose, gander, swan, flamingo, or other aquatic bird" and he notes that it can refer to a poetical or mythical bird.[12] Although popularly thought of as a swan, particularly in modern India, ornithologists have noted that swans do not, and never have, existed in the Indian avifauna,[13] and Western translations tend to plump for 'goose',[c] or 'flamingo';[d] 'crane' is also a possibility.

Genre

[edit]The saṃdeśa kāvya ('messenger poem') genre is one of the best defined in Indian literature. There are about 55 messenger poems in Sanskrit,[14] plus others written in vernacular tongues. These span India chronologically, topographically and ideologically: there are Muslim and Christian messenger poems, and poets are still composing these poems today.[15] Each follows Kalidasa's Meghaduta to a greater or lesser extent. They involve two separated lovers, one of who sends the other a message, and thus are designed to evoke the śṛṅgāra rasa ('feeling of love'). And they adhere to a bipartite structure in which the first half charts the journey the messenger is to follow, while the second describes the messenger's destination, the recipient and the message itself.

Metre

[edit]The metre used in Alagiya-Sandesha is the slow mandākrāntā ('slowly advancing') metre which is thought to be suitable for the love-in-separation theme. The specifications of this metre are encapsulated in the following line (which is itself set to the mandākrāntā rhythm):[e]मन्दाक्रान्ता जलधिषड़गैर्म्मौ नतौ तो गुरू चेत्

- mandākrāntā jaladhi-ṣaḍ-agaur-mbhau natau tād-gurū cet

The line means, by way of several technical abbreviations, that the mandākrāntā metre has a natural break after the first four syllables and then after the next six, with the last seven syllables as one group. It is further defined as containing several different gaṇas, i.e., poetical feet consisting of predefined combinations of guru and laghu – long and short – syllables.[16] When each line is scanned it looks like the following:

- (– – –) ( – | u u ) ( u u u ) (– | – u) (– – u) (–) (–)

with the vertical bars representing the natural pauses and the brackets the predefined feet. Each stanza consists of four lines or pādas.

In European terms, the scansion may be written out as follows:

- | – – – – | u u u u u – | – u – – u – x |

Commentaries

[edit]Commentaries include one by Agyatkartrik.[f]

Views and criticism

[edit]The Alagiya-Sandesha was written during the medieval literary resurgence, long after the classical heyday of Sanskrit literature, and falls into the category of post-1000 CE regional Sanskrit literature. Such literature tended to enjoy less national recognition than its predecessors and in modern India literary works of this type are all but forgotten.[2] The Alagiya-Sandesha too has slipped into obscurity for all but Sri Vaishnavas.

What criticism and discussion there is tends to focus either on the Alagiya-Sandesha in the shadow of the Meghaduta,[17] or on its religious and philosophical significance. Modern Western scholarship on the poem and its author includes books and articles by Stephen P Hopkins,[18] and by Yigal Bronner and David Shulman.[2]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Compare for instance the identical position of sa kāmī at the end of a line in Meghaduta 1.2 and Hansa-Sandesha 1.1

- ^ Compare for instance Ramayana 6.5.6 and Hamsa-Sandesha 2.40

- ^ See translation of the Hamsa-Sandesha in Bronner & Shulman 2006

- ^ See translation of the Meghadūta in Mallinson et al. 2006

- ^ For Mallinātha's note on the definition see Meghadūta 1.1 in Kale 1969

- ^ This commentary can be found in the Chaukhambha edition of the Haṃsasandeśa.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Hopkins 2002, p. 314.

- ^ a b c Bronner & Shulman 2006.

- ^ As detailed by Hopkins 2002

- ^ Verses 1.2-1.7

- ^ Verses 1.8-1.60

- ^ Verse 2.7

- ^ Verse 2.8

- ^ Verse 2.9-2.23

- ^ Verses 2.31-2.46

- ^ Verses 2.48-50 respectively

- ^ Verse 1.2

- ^ Monier-Williams 1899, p. 1286.

- ^ Ali & Ripley 1978, pp. 134–138.

- ^ Narasimhachary 2003.

- ^ Hopkins 2004.

- ^ Apte 1959, vol. 3, appendix A, p. 8.

- ^ See Bronner & Shulman 2006

- ^ Hopkins 2002 and Hopkins 2004

Works cited

[edit]- Ali, Salim; Ripley, Sidney Dillon (1978). Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 134–138.

- Apte, V. S. (1959). The Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Poona: Prasad Prakashan.

- Bronner, Y.; Shulman, D. (2006). "A Cloud Turned Goose': Sanskrit in the Vernacular Millennium". Indian Economic & Social History Review. 23 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1177/001946460504300101. S2CID 145438393.

- Hopkins, S (2002). Singing the Body of God: the Hymns of Vedantadeshika in their South Indian Tradition. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512735-8.

- Hopkins, S. (2004). "Lovers, Messengers and Beloved Landscapes: Sandeśa Kāvya in Comparative Perspective". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 8 (1–3): 29–55. doi:10.1007/s11407-004-0002-2. S2CID 144529764.

- Kale, MR (1969). The Meghadūta of Kālidāsa (7th ed.). New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas.

- Mallinson, James; Kalidasa; Dhoyi; Rupagosvami (2006). Messenger poems. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-5714-6.

- Monier-Williams, Monier (1899). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Osford: The Clarendon press.

- Narasimhachary (2003). The Hamsa Sandesa of Sri Vedanta Deśika. Sapthagiri.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Venkanatha, Acharya (2004). Hamsasandesa of Acharya Venkanatha. Varanasi: Chowkhamba Krishnadas Academy.